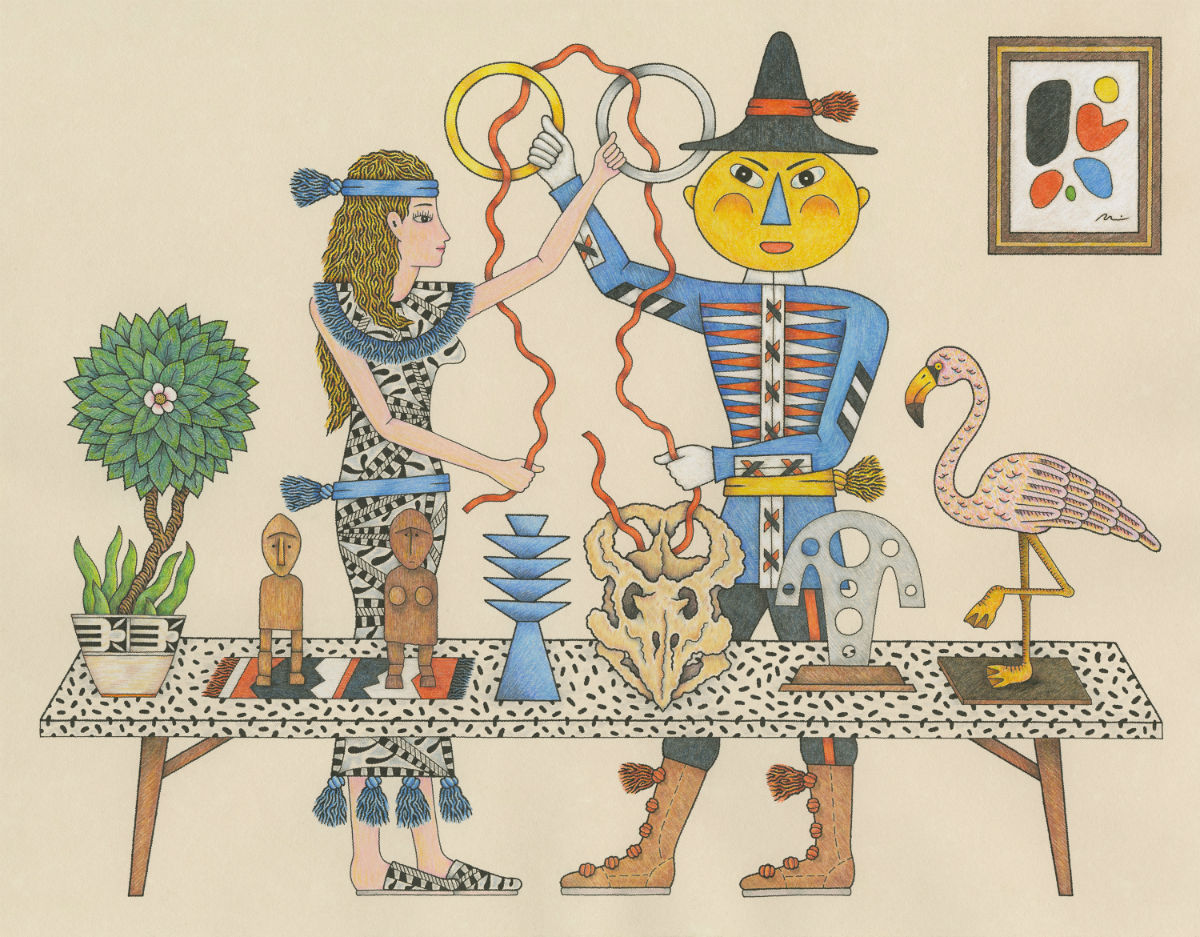

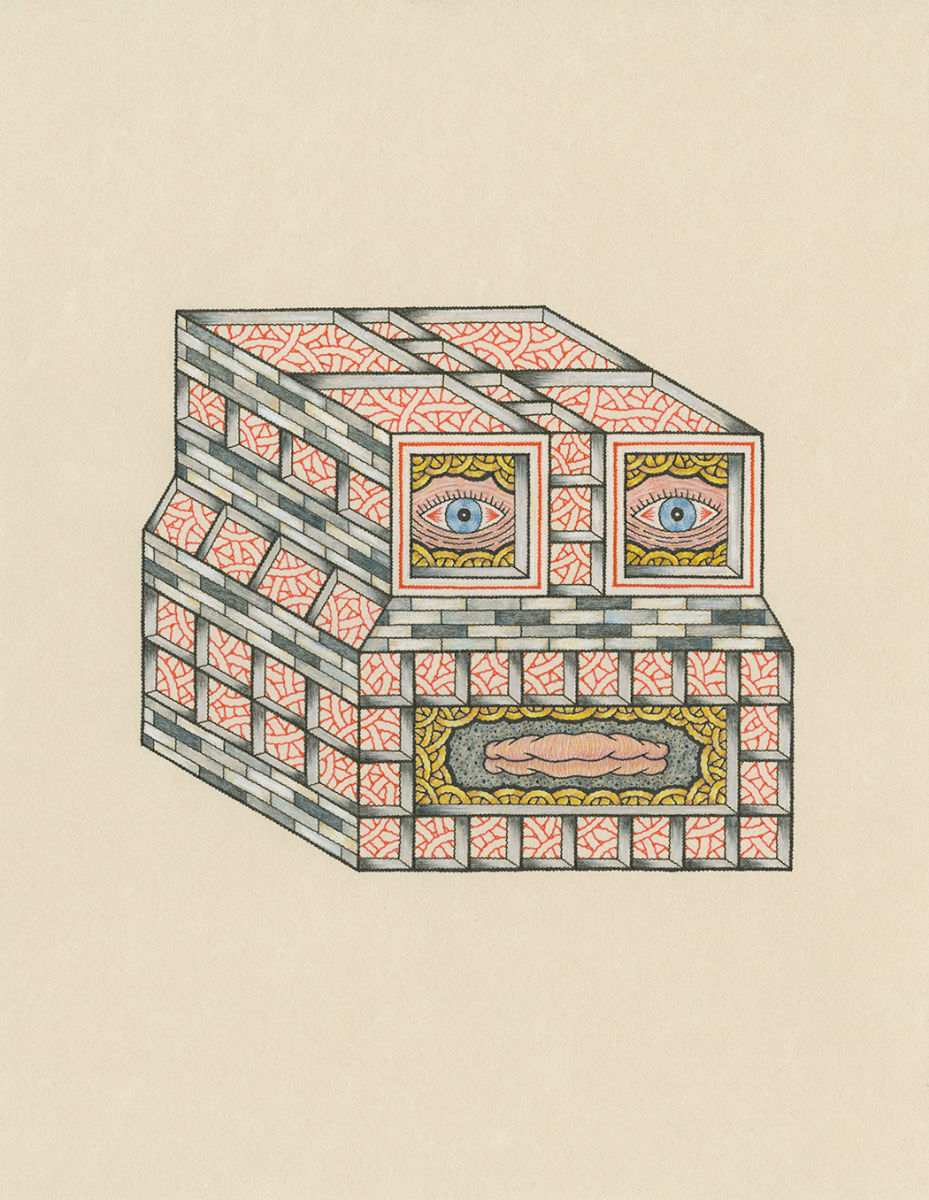

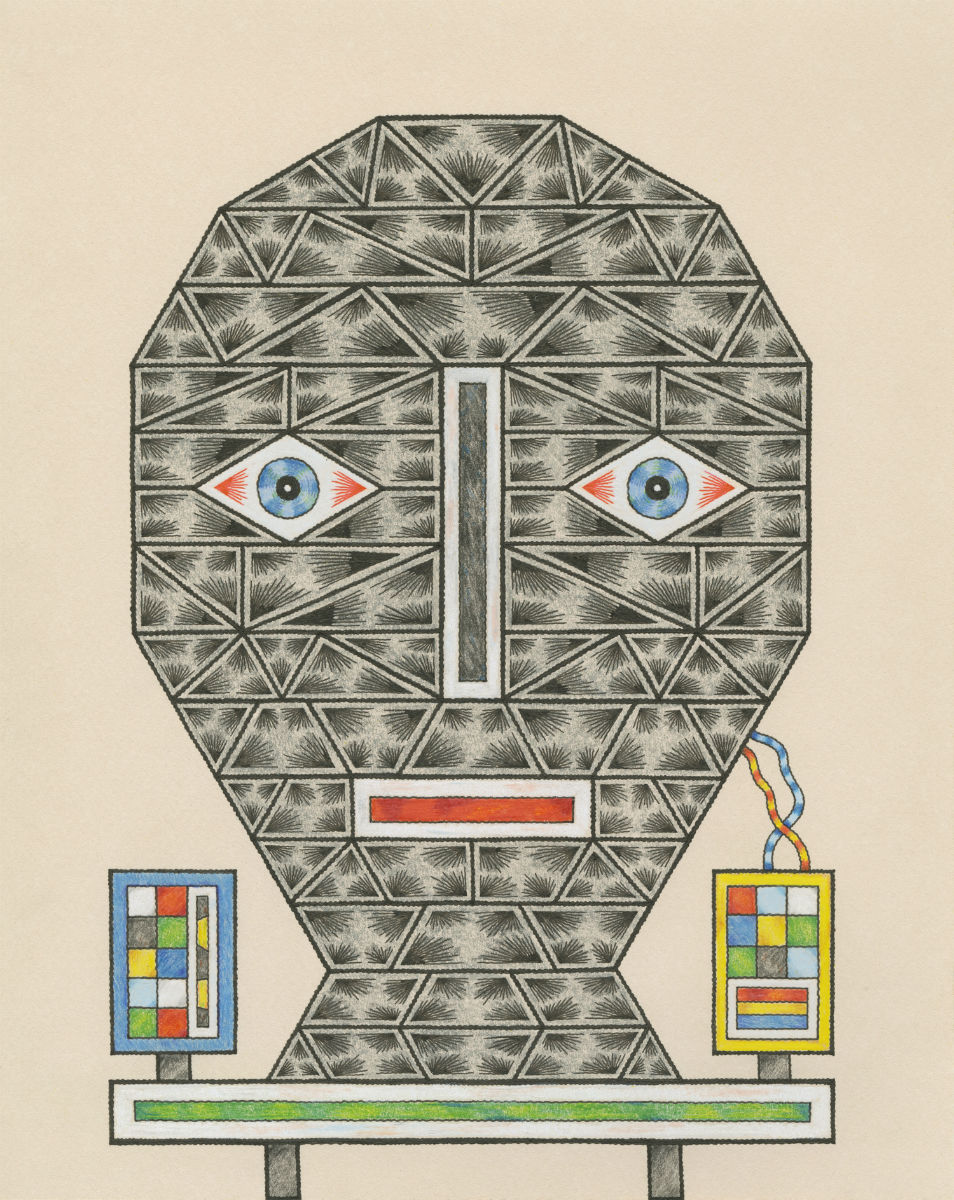

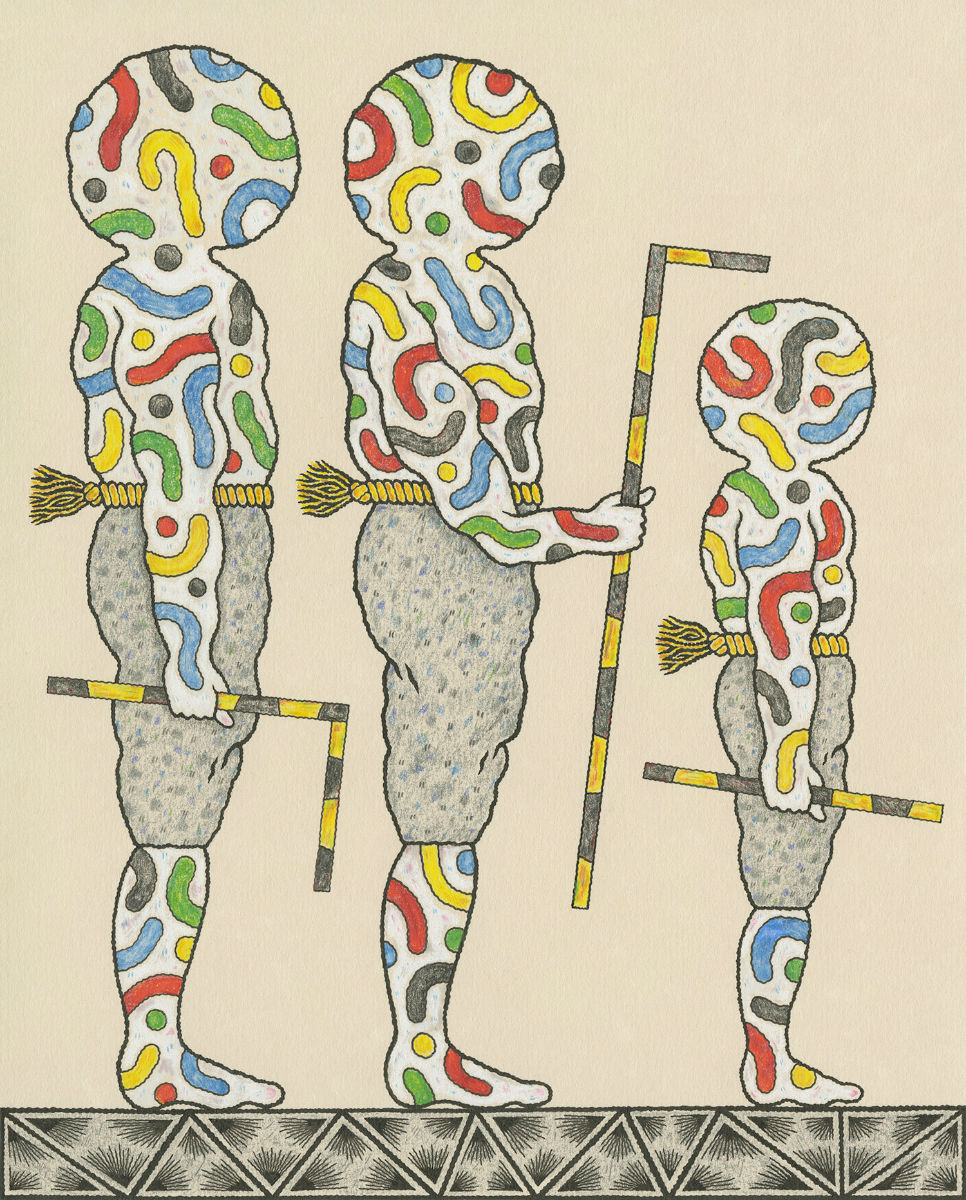

Matt Leines’ masterful and mythical worlds are filled with fantastic characters, cryptic iconography, and serendipitous color planes. They exist in an eye-pleasing geometry that is seemingly ruled by its own mathematical formula. His artwork resonated so deep in the early 2000s that the art world snapped to attention, propelling his career forward like a double-edged lightning bolt. But science predicts that every peak is followed by a valley, and a forced hiatus gave Matt the time to reflect and revive his practice. The result is a new style of unlimited potential, and his new technique adds up to large and lofty.

This is an excerpt from the February, 2015 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Joey Garfield: Have you always had that scar? Does that have something to do with your eye?

Matt Leines: That was a bike accident, completely unrelated. My vision was fucked up for twenty years before that. In sixth grade, I got glasses to help correct my eye problem. I was given strengthening exercises to practice, like using a penlight and red filters, but sixth graders don’t do shit like that.

I can make myself see double but I never realized that you normally can’t. As a kid, if you have an experience, you’re going to assume it’s the same as everyone’s. I’m told I could get surgery but it wouldn’t fix my vision and would just be cosmetic. Part of me doesn’t want to know. This is the way I see, so why risk that?

That’s like Freddie Mercury from Queen choosing not to get his teeth fixed because it could alter the way he sounded when he sang.

Exactly. There are moments when I see things differently. I feel like everything just flattens out. At the store, if someone is handing me change, I’ll misjudge where their hand is, but I feel like my mind corrects for it. I’ll see things in outlines instead of tonal differences, and with the depth stuff, geometrically, I understand how things work, so it immediately corrects. But I don’t think I see it the way most people do.

So, flatness isn’t just a style choice, it’s how you actually see?

I’ll see stuff in 3D. But I also don’t know what everyone else sees, so I’m guessing. The way things have been described to me, I know I’m... off. That’s probably the best way to put it.

I’ve noticed a change in your recent style and subject matter. It’s not so much flat as it seems more flowing.

When I first started making stuff, it was all based on patterns and lines. If someone suggested I should draw something specific, if I didn’t know how to translate that to a specific set of shapes, I wouldn’t do it. Now I feel like I’ve added enough things to it. I’ve broken rules and figured out enough now that anything is on the table, and that’s super new and I’m excited by that.

Your past work had a kind of unique geometric equation that seemed to rely on rules, and you mention breaking rules. Isn’t it good to have rules?

I mean, it got me to a certain place, but ultimately, it was limiting. It’s difficult. It took me years to follow those rules, and to break them feels like such a big deal. Most people may not even pick up on them.

What were some of them?

There were so many rules. A lot had to do with color. One rule was that I would never draw directly from the source, like an image from a book. If I saw something in a book, I would draw it in my sketchbook, but only base everything off that sketch. Everything had to be one degree removed.

Flatness is a rule. I would try to get everything to look flat, like it was printed, and though it was never going to look printed that way, I would keep chasing it anyway. As time went on, the weird individual things started to disappear and everything took on more uniformity. I had one way to draw grass.

Oh, I see where the trees all have U-shaped curved branches, and you don’t stray from that at all.

Exactly. This is how I do this one thing. Another rule was eliminating anything that was too obvious of a connection. In the beginning, guys would wear tracksuits and sneakers, and later on, everyone needed to be in loincloths. I don’t know why, but it just happened that way. That became more important than variety in the drawings. Now, it’s sometimes the case, or the reference, which I don’t want to be too obvious. I wanted it to be special unto the world I was creating. But that’s too short-sighted of an idea.

Did all those rules take the fun out of the art?

It really did. But I didn’t know it at the time. Doing all the little stuff, like grass, is super therapeutic to me. The moment of doing that is meditative, so to recognize that it’s ruining the fun doesn’t happen right away.

How did you recognize the limitations?

It happened when my book came out. Everything was happening so fast back then. I showed very quickly out of school, and it took off for me, though I didn’t know how it worked until I got started. When I got started, it was a rocket ship that reached a point and crashed. There were a few years of being told, “Oh, this happens, so just be patient.” But places go out of business and everyone needs to diversify their roster. And you get dropped. Once I put the book together, I saw it all again in one place, and after seeing that, I had a different response and I wanted to make this complete break. Keep in mind this was when the economy tanked. In my mind, if there were ever a time to fuck around, this was my window to see what I could do.

What did you do?

I went back to acrylics. I kept trying different things to get closer to what things are supposed to look like in my head, and painting played a big part. What I had been most known for was the ink and watercolor drawings. Since I wanted everything to look flat, that limited my palette. I went back to acrylic painting to completely blow that open and found it also had its limitations because the process was reversed. When I draw, I do all the line work and then color; but with painting, you do all the color and the line work last. That never got comfortable and always felt weird.

The paintings did allow me to use more colors. At first, my drawings were limited to black, red, and grey, and then yellow as I developed. But I couldn’t add blue. Basically blue is the reason everything keeps changing. When I was using it with ink and watercolor, it was the one color I couldn’t get to look flat. So, every time I used it, I would hide it behind a pattern, which was a lot of work just for something to be invisible. One of the reasons I went back to painting was to have more possibilities and loosen up because you can paint over things.

But going back to acrylic painting after drawing didn’t mesh. It never felt right. I prefer doing the drawing first because, as I'm drawing, I start to see what the finished piece will look like in my head. It feels more natural and I have more control over making it look as I intended.

I was hoping to accomplish too many things at once. I changed the scale, the subject matter and the material, so it was probably destined to fail. Then, by accident, this “rope image” became the first finished piece from this new way of working.

----

Read the full interview in the February, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz, available here.