Designer Oleksandra Gerasymchuk’s Autodiscipline jewelry series physically alters those wearing her pieces, aligning them into perfect posture. The wearer shifts her body, making clear the relationship between fashion and self mastery. Gerasmchuk created the series as part of her university studies at the Higher School of Art and Design of Saint-Etienne, France.

In collaborating with jewelry craftsman Florent Gros, the pieces took nine months to create and made their debut at the International Biennale of Design of Saint-Etienne, an exhibition inspired by “les sens du beau,”—the senses, meanings, feelings, or directions of beauty.

Rachel Cassandra: What is the experience of wearing the three sets of jewelry in this collection?

Oleksandra Gerasymchuk: Wearing them reminded me of my first ballroom dance exercises when you have to keep your shoulders straight and "open" and imagine your head is linked to the ceiling by an invisible thread so that you have to walk like you’re floating. It wasn't a bad feeling. I had to constantly pay attention and slow the way I moved, but having my back straight changed the way I was walking. It actually felt and looked surprisingly good.

These pieces remind me of other traditional forms of jewelry like the neck coils in Myanmar. Tell us more about the relevance of posture in your work?

Your example is one of many interesting pieces of traditional jewelry that inspired us to focus on the link between posture and beauty. I wanted to go deeper and rethink jewelry not just as an adornment but as an object changing behavior, or even personality. This appears quite disturbing as it's hard to accept that jewelry can influence the whole body this way. But this collection is the result of observing people either acting differently while wearing accessories, or choosing not to wear them at all. So making the posture a guideline of the Autodiscipline collection is a different way to express the reality.

Often, the discomfort associated with fashion and beauty is invisible. What is your aim as you make this relationship visible and salient?

Our collaboration for this project is inspired by the theme of the International Biennale of Design of Saint-Etienne, for which we made the collection. The theme was "Les sens du beau" which you could translate as "The meanings or directions of beauty." I collaborated with Florent Gros, a jeweler craftsman. We wanted to highlight the idea that beauty is sometimes linked to discomfort in a very disturbing way because, as you said, usually it is invisible or unnoticed. We all know about it, but it's been part of our life for such a long time that it has become a norm. Florent and I agreed that in order to look better in front of other people, we sometimes accept feeling disturbed or uncomfortable. This has become usual and normal and we accept discomfort as part of the process. By emphasizing the role of the jewelry, we wanted to show how much we can be influenced and dependent on beauty standards. Each piece is meant both to adorn and to alienate, physically and psychologically, so that the collection transforms from glorifying jewelry to show devices parasitizing a body.

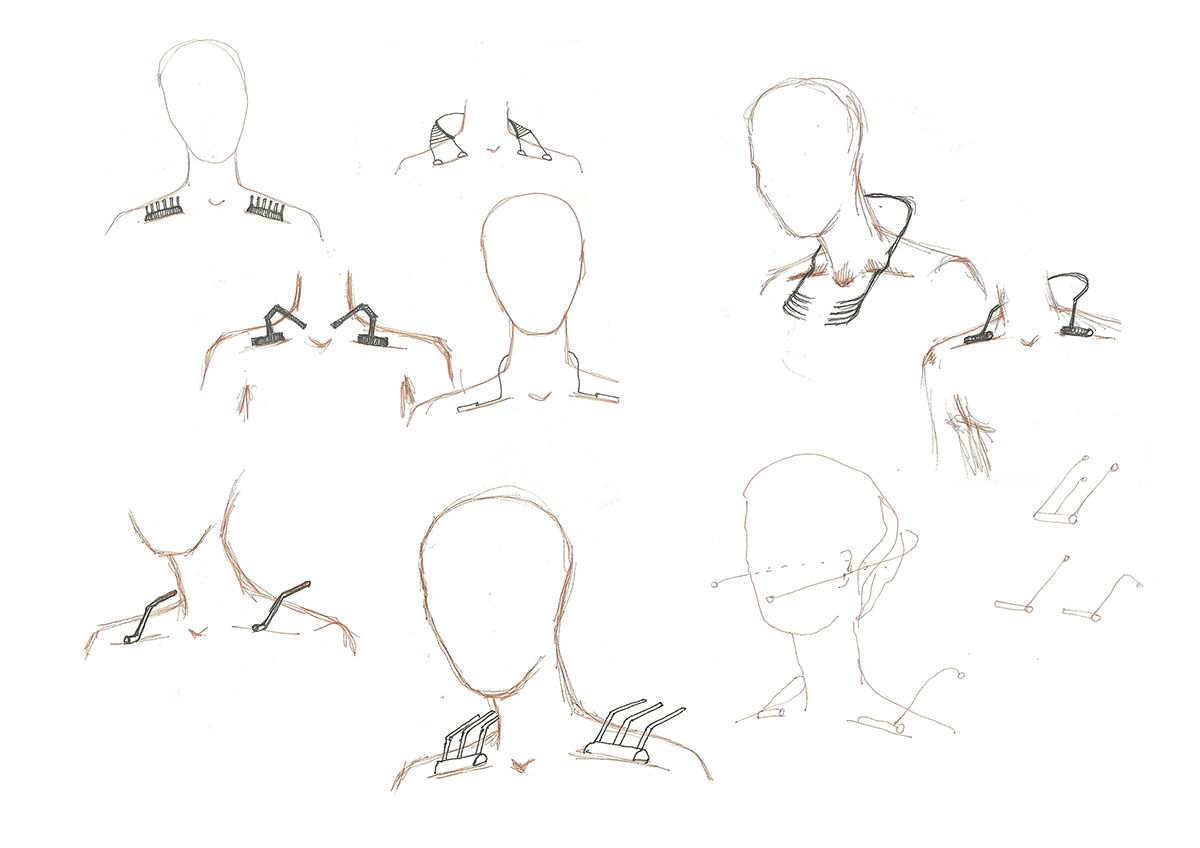

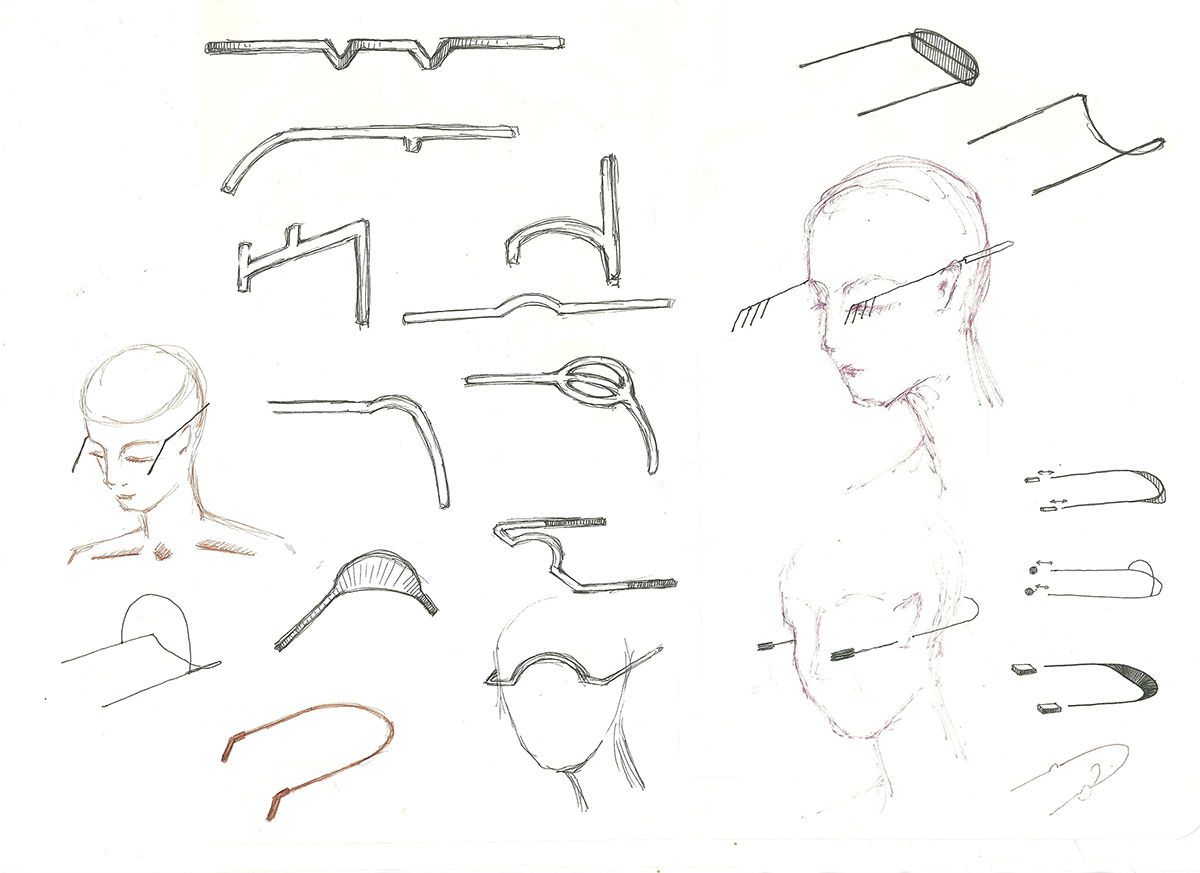

Now that you’ve shared some of the process sketches associated with this collection, I’m curious about how you arrived at the final model.

The creative process was quite fluid but many tests were needed before we could find the perfect shapes. We worked with a physiotherapist to make sure that each piece influences and controls posture in the anatomically correct way and won't cause health complications. The jewelry mainly influenced the back. We learned we had to create the piece with the correct weight and make sure it was worn properly, or it could cause real health issues. Lots of first draft models were needed to understand the shape that would perfectly fit the chosen body parts. The earpiece needed the most work; we had to find the perfect weight of both the front and the back parts so it balances around the head of the model.

The pieces seems to have an aesthetic and functional relationship to medical devices. Did they inspire you visually?

Medical devices have very clear and recognizable shapes because their forms follow their functions. We also wanted to highlight the very sensual parts of the bust—the neck and the clavicles—so we decided that each item be a simple and striking shape, reflecting light as much as possible so the piece becomes a bright and delicate outline drawing attention to those body parts.

How does this piece aim to examine and ask us to rethink beauty standards?

Our main purpose was to rethink the aesthetic values and to show that what do you wear doesn't really matter, but the way you wear it is essential. As I already mentioned, this collection changes the way you move and walk, and the way someone walks tells a lot about the person. Your walk and the posture are the way you present yourself to the world.

---

Read more in the March, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz, on sale here.