Timothy Taylor is pleased to present Sugar, an exhibition of new paintings by Sahara Longe. Featuring twelve vivid and haunting canvases, Longe’s second exhibition with the gallery sees the artist reconceiving various art histories to arrive at an uncanny interplay of figures, allegories, and enigmatic landscapes. The show will be accompanied by an essay by Ferren Gipson, art historian and writer based in London.

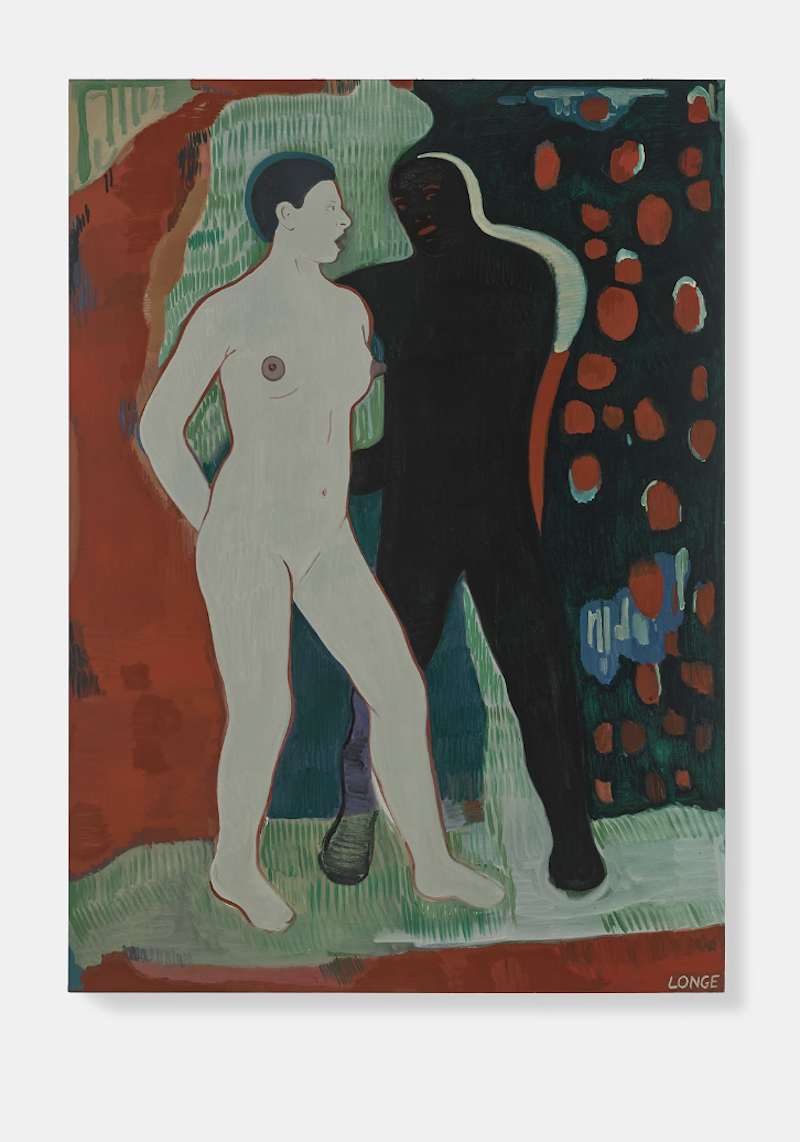

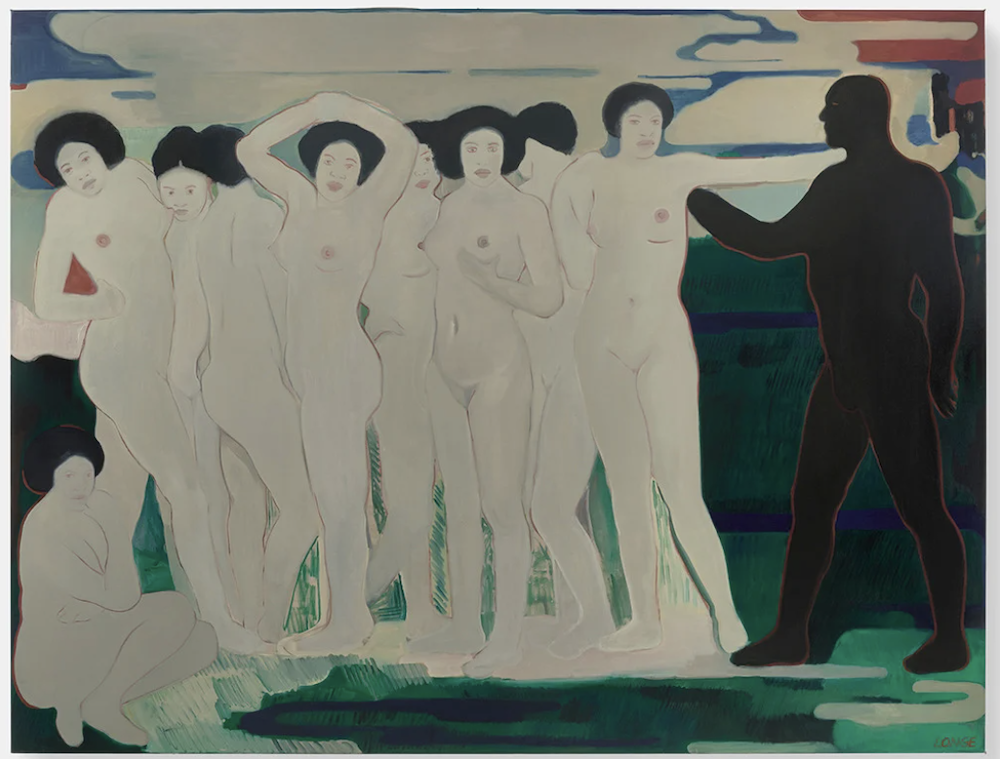

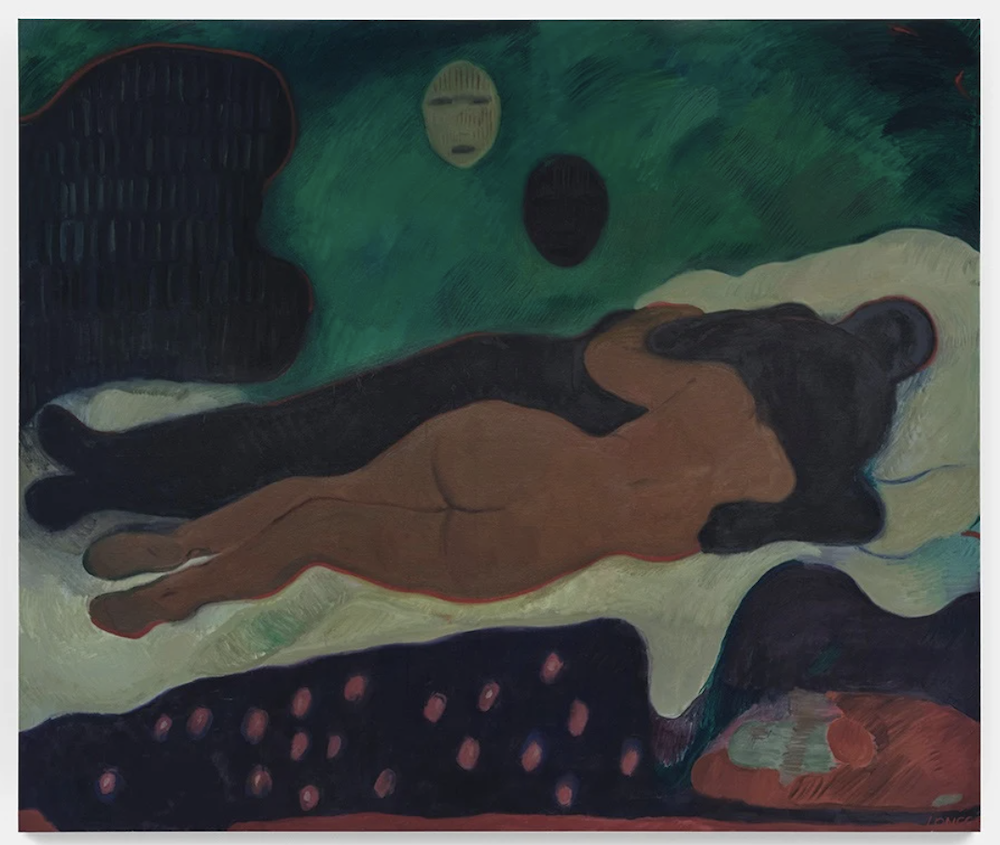

In paintings characterised by a preternatural handling of line, colour, and figuration, Longe depicts partially abstracted subjects in atmospheric environments. Working on thick grain linen with raw pigment in a distinct palette of vermillion, lilac, raw sienna, and ochre, she renders her scenes with a fluid painterly freedom that is nevertheless quiet and precise in its effect. Across her work, she recalls aspects of the Symbolist ethos, which moved between nostalgia and rupture, seeking not to capture something directly, but rather convey the sensations it produces.

In her new paintings, Longe focuses on the nude. Articulated in spare, suggestive gestures, her subjects, largely women, are pictured huddled together, embracing a lover, or striding alone. Some set their gaze on an unknown distance, others stare down the viewer, and one confronts a fish. Each seems possessed by a disquieting tension that is emphasised by a shadowy apparition lurking in many of the works. Masculine in stature, the incubus perches over a scene or cradles another figure therein. Where Longe’s previous series reflect on social dynamics, depicting parties and crowds, these paintings are more personal; the artist explains that the new works look inward rather than outward. Expressive, brushy marks bring subtle notions of agitation, dreaminess, and intimacy to otherwise minimal passages of colour.

These paintings further explore the ideas set out in Longe’s earliest work, which emerged from her study of classical portraiture at Charles H. Cecil Studios in Florence; in her early canvases, Longe integrated and recontextualised themes and styles of old-master paintings. Here, her compositions draw from Secessionist painter Otto Friedrich’s nudes and Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler’s ominous portraits. They likewise reveal the influence of a recent trip to Oslo, where Longe was taken by Henrik Sorensen’s mural (1938–50) in Oslo City Hall (where the Nobel Peace Prize is selected), and the marginalia of illuminated manuscripts. Ushering these disparate sources and traditions into her singular aesthetic, Longe poses subtle questions about representation—who it serves, and what narratives it upholds—just as she underscores figuration’s expressive potential.