Two powerful and eloquent artists, Ana Teresa Fernández and Arleene Correa Valencia have solo shows at Catherine Clark Gallery this month. Both exhibitions unfold with epic force by holding a mirror up to the world in ways that both contain and shatter our ways of seeing.

Fernández is an artist of actions. She places herself physically in space, time, and circumstance, capturing site-specific interventions on film and then “freezing” certain frames in masterful life-sized oil paintings and photographs. Like a poet, she also uses metaphor to great effect through sculpture.

During the crackdowns that marred the Obama years, Fernandez sought to shine a light on immigration policies and practices that weren’t penetrating the national consciousness through the drumbeat of daily reporting. She set out to transform the man-made structures that have been installed to divide the United States and Mexico by painting sections of the wall the color of the sky. The photographs on display of this lyrical act provoke an immediate effect. What could be more limitless than the sky itself? And yet, we cut ourselves off from each other and divide families with artificial barriers. This is but one example of how Fernández makes walls intolerable through the act of “erasing” them.

Fernandez wipes away psychological barriers when she challenges physical ones. She tears down the unconscious loss that othering erects and restores lost connections. In addition to rewiring the channels of human empathy, this body of work, Borrado La Frontera (2011/2021) fosters an ecological recovery by enabling the viewer to witness the boundary between the natural world and ourselves “vanish” from this otherwise pristine section of beach.

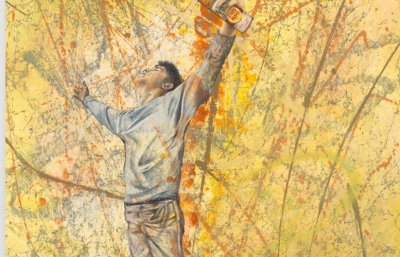

At the Edge of Distance (2022) extends the artist’s exploration of borderlands at a time when the inhumanity of immigration enforcement in Trump-rattled America is even more urgent and visible. “Visible” cuts both ways. Hard facts often prompt us to turn our eyes away in sorrow and hopelessness. To flee the impact, we seal our imaginations off to the pain of others as a form of self-protection, constructing another barrier; this time a self-imposed one. Fernández’s art offers us an alternate mode of visualization. She gives us beauty as a path to more clearly face what is beastly in this world and to challenge its gaze.

In this newest body of work, Fernández suspends (either on a laundry line above the sand or in her hands held high) one of the reflective blankets NASA first developed for exploration of humankind’s vast potential through space travel. She allows the billowing silvery “mirror” to mold to her body. The sensuous appeal of the statuesque artist thus draped calls to mind a Hollywood starlet or Hellenic goddess, until it registers with us that her face and identity have been completely obscured and that these are the same blankets given by border guards to families cut off from each other in the ice-cold cells of detention camps.

Sometimes a work of art can both break and reawaken the heart. Fernandez’s transfixing performances and the paintings that so luminously memorialize them achieve this. They reveal the shortest distance between one human life and another, between how we are and how we hope to be.

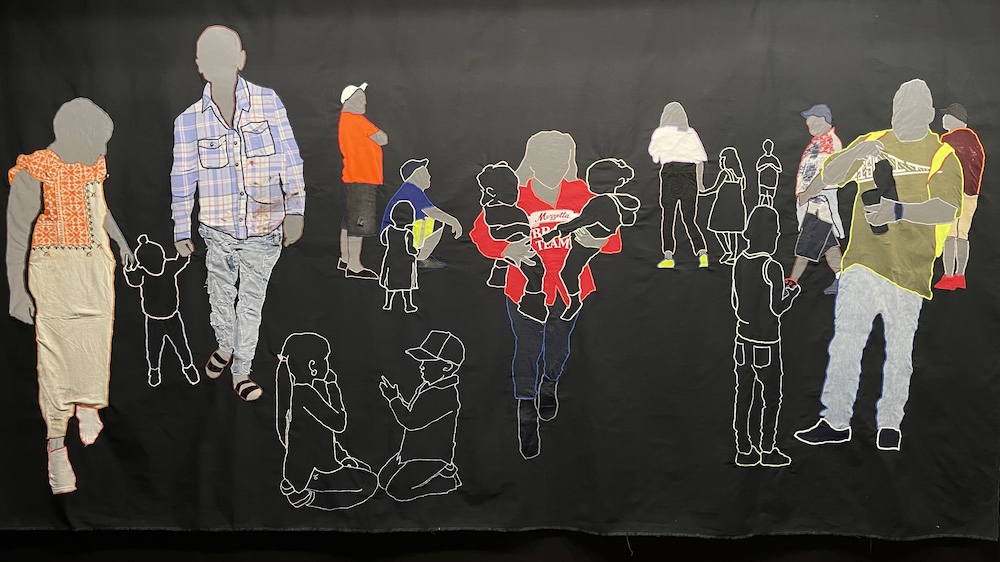

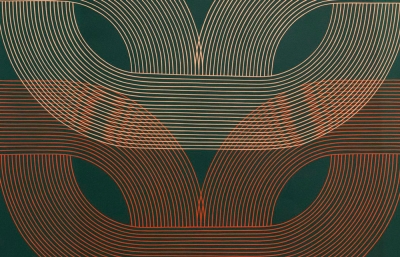

In the gallery’s Viewing Room, Arleen Correa Valencia employs textiles and works on paper to tell the stories of families crossing the border. In her exquisitely sparse and potent compositions, Correa Valencia uses silhouettes of parents and children to outline chapters of painful separation and transcendent emotional intimacy. These trace the pattern of migration, loss, and mending from her own history. The title of the show is drawn from a letter written to her father in 1996.

Hers are not store-bought textiles; they are relics of her family experience. She uses these pieces of cloth and mirror-like reflective fabric – which have hidden as well as protected her loved ones – to maximal impact. As Bay Area Figurative artists used simple shapes and color blocks gesturally to project a deeper emotional message than surface-level likeness would allow, Correa Valencia’s tapestries often collage only 2 or 3 simple fabric swaths onto a base. Infants and toddlers are represented as cut-out figures captured in basic stitchwork. The deft use of positive and negative space creates an almost physical experience for the viewer. We simultaneously feel the rending of separation and the ache of a connection that can never be torn apart.

Ana Teresa Fernández and Arleene Correa Valencia invite their audience to step out of the role of bystander and into the arena of common cause. By pulling us though the looking glass, they make the unimaginable imaginable and therein begins our work. —Tamsin Smith