Night Gallery is thrilled to announce Reliquary, an exhibition of new paintings by Jesse Mockrin. This marks the artist’s fourth solo show with the gallery and will be accompanied by an exhibition catalogue with an essay by Norman Bryson.

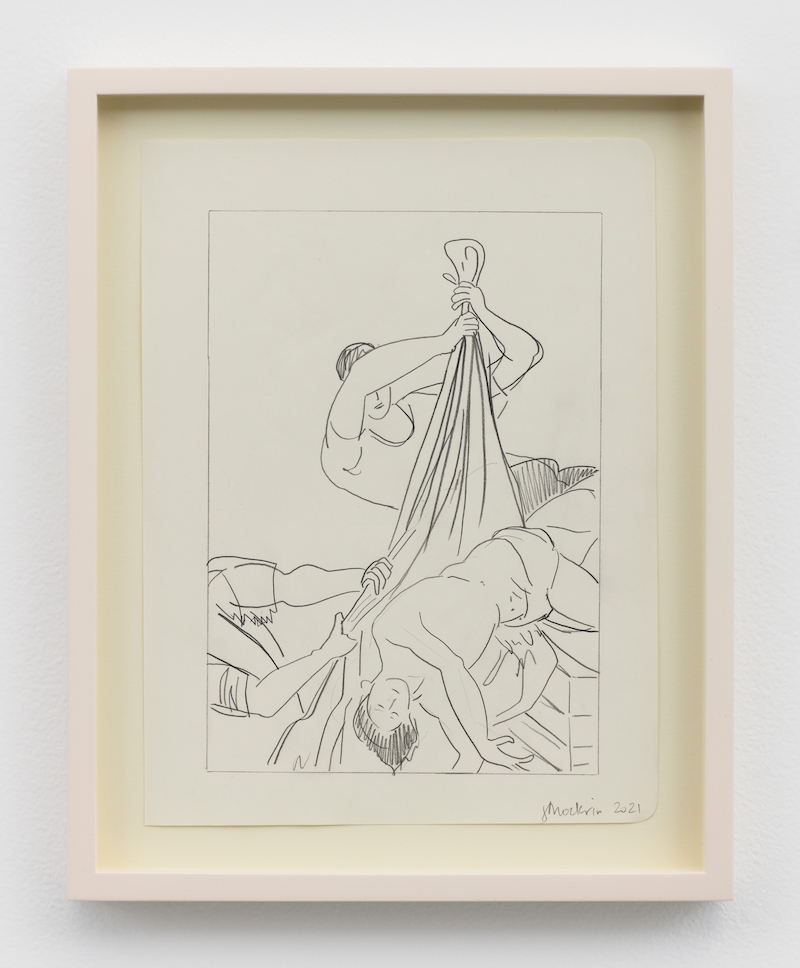

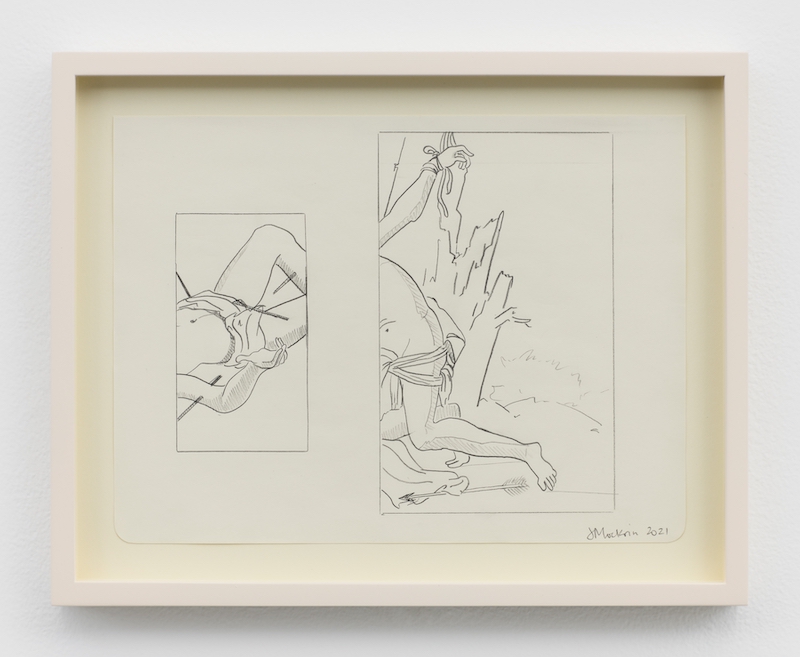

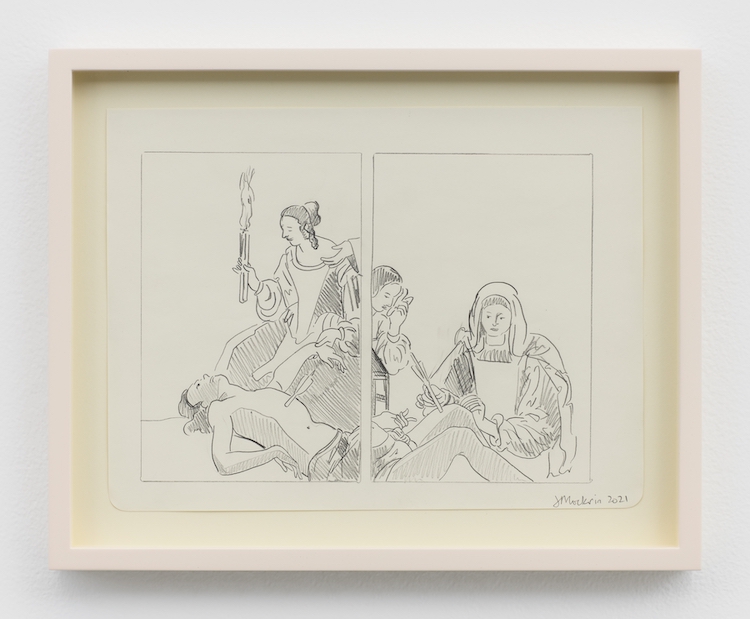

Jesse Mockrin is known for her virtuoso oil paintings that destabilize art historical tropes and dominant representations of gender, power, and sexuality. Recreation is a cornerstone of the artist’s practice, as she continuously looks to iconic paintings from the Renaissance, Baroque, and Dutch Golden Age to forge her own masterful works. But reference all but dissolves following the initial citation: unorthodox croppings of bodies and scenes, often covering multiple panels, disrupt the conventions of the source image, its creator(s), and the broader historical context from which it originates. Cultural transformation is a central preoccupation for Mockrin, made legible within her paintings so committed to the confrontation of hegemony.

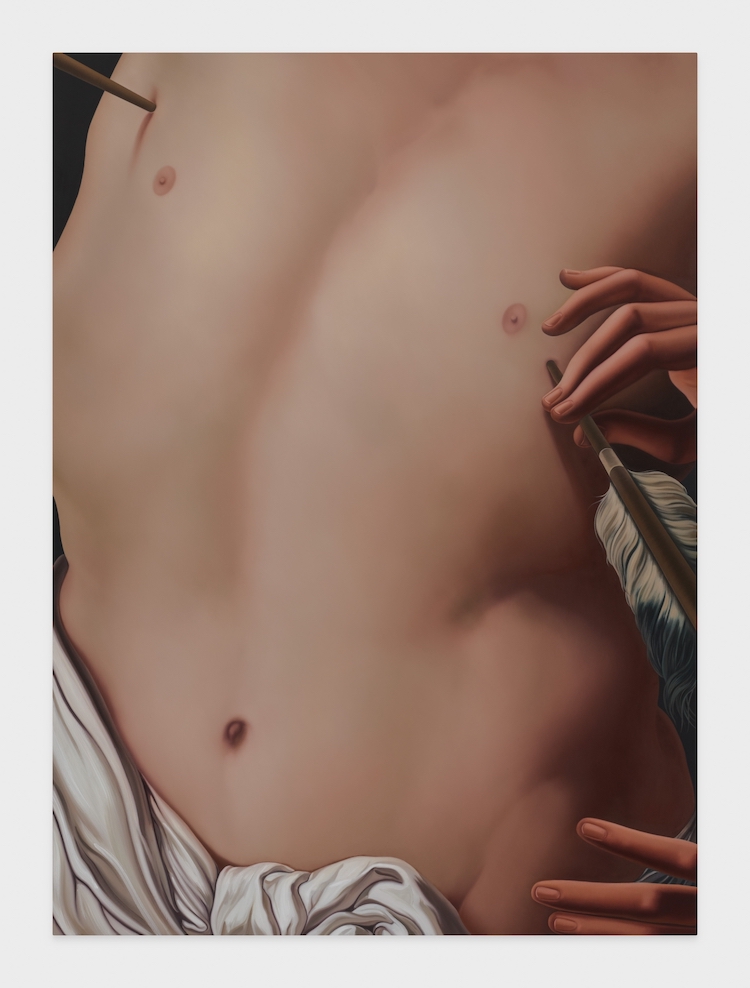

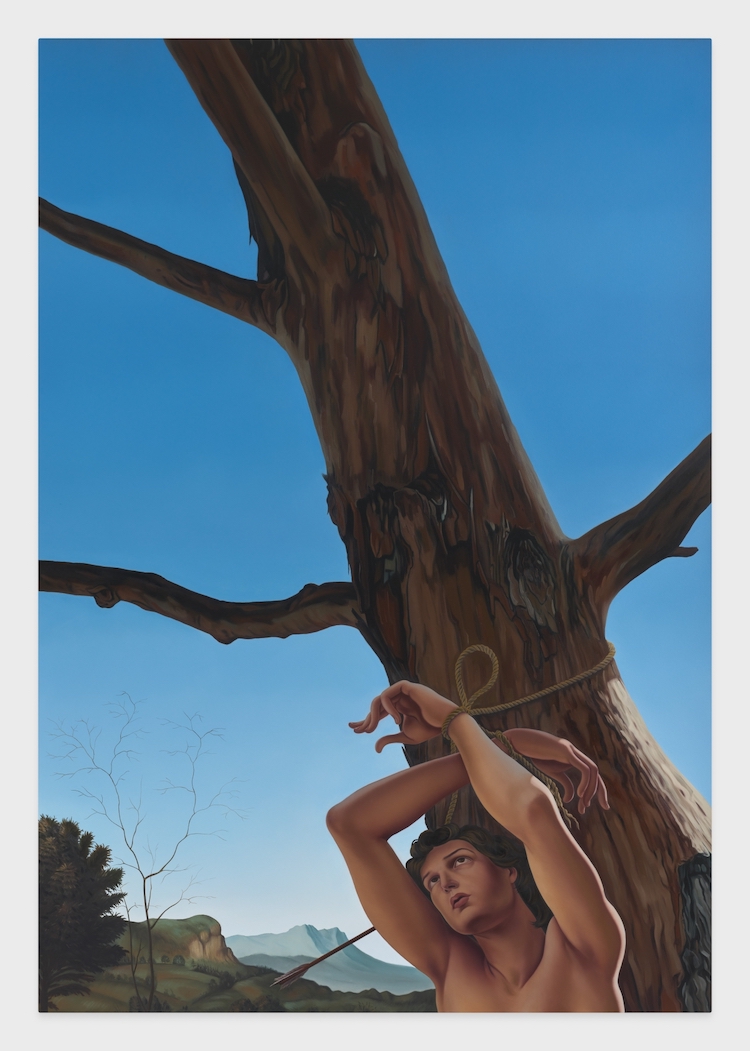

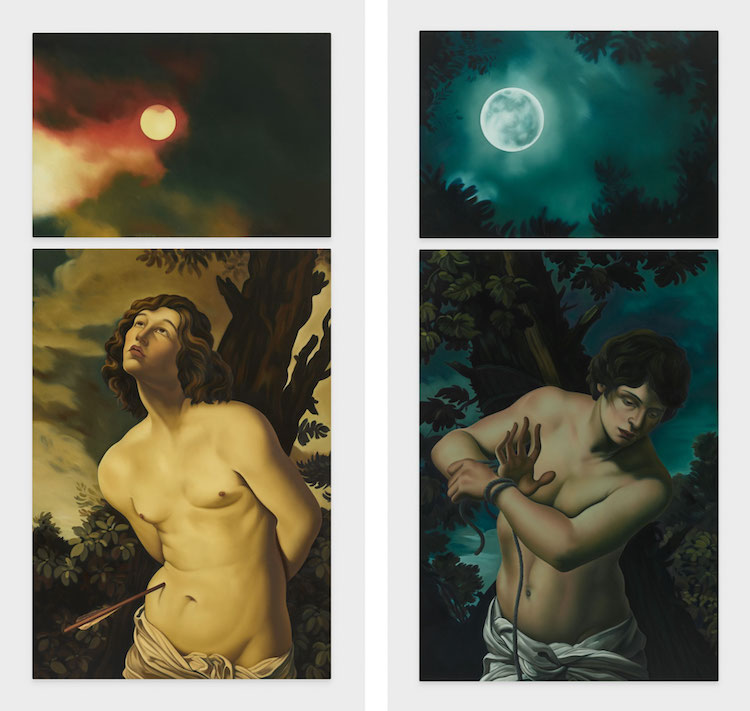

For Reliquary, Mockrin turns her attention to Saint Sebastian, who survived being shot full of arrows to become an unexpected icon. The figure’s meaning and his subsequent visual depictions have evolved and diversified through history: from Christian martyr, to savior from mass disease, to queer sex symbol. Working off of paintings from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, Mockrin cohesively unites portrayals of Sebastian across time and circumstance. The saint—already rooted in the Western cultural memory as gender-complex—is reimagined by the artist’s hand to accentuate androgyny. Sebastian’s skin is made smoother, his musculature and testosterone reduced, allowing for the fluidity of gender to come to the fore.

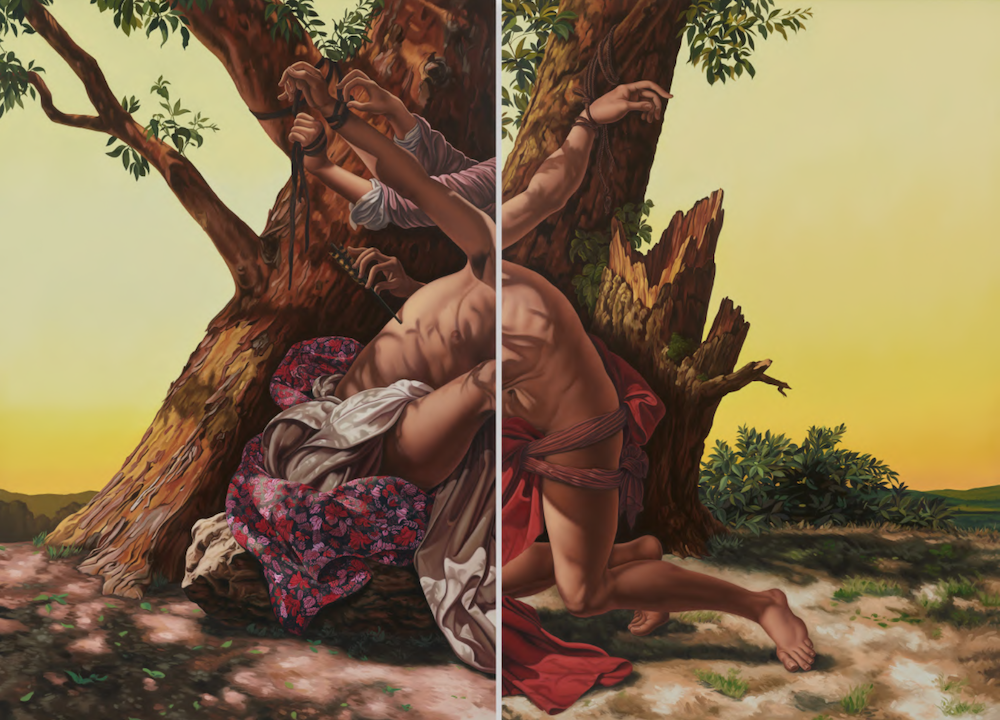

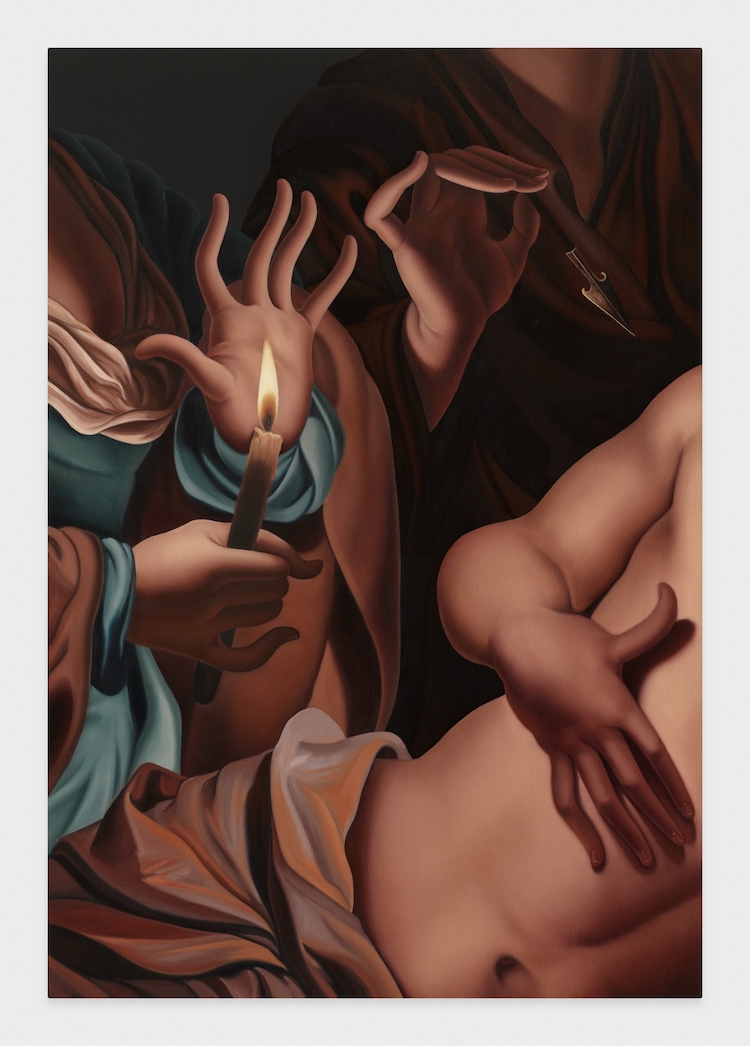

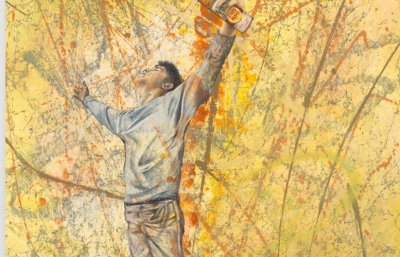

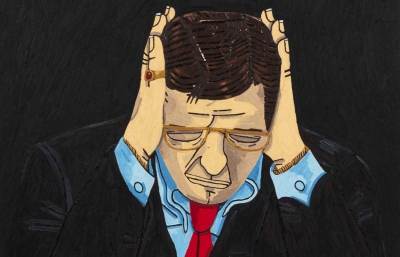

In the monumental diptych Transfiguration, 2022, Mockrin places on the left a section from Hendrick ter Brugghen’s Saint Sebastian tended by Irene, 1625; on the right, the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, 1789 by François-Xavier Fabre. Here, two Sebastians bridge the divided canvases, giving rise to a new body in transition: between life and death, night and day, the debilitation of his injuries and the restorative promise of Saint Irene’s aid. The boneless, disembodied hands of Saint Irene evoke similar dualities as they reach for Sebastian’s bonds and remove a penetrating arrow, his liberation bound up in simultaneous tension and tenderness. Mockrin’s landscape mirrors these contradictions: the harsh, acid sky of the background contrasts with the soft, dappled light suffusing Sebastian’s form.

Among his myriad designations, Saint Sebastian is the patron saint of plague. In our contemporary moment, rife with precariousness, Mockrin finds a subject worthy of revisitation. Within Reliquary, we are prompted to consider the fragility and resilience of the body as Sebastian flickers between the righteousness of sainthood and the full complexity of human existence.