56 HENRY is pleased to present Second Growth, an exhibition of new work by LaKela Brown.

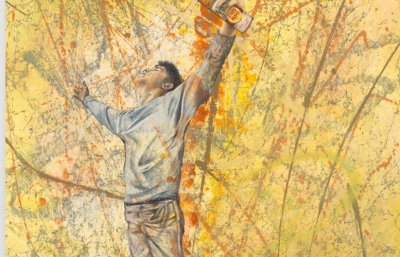

After a primeval forest is cleared for cultivation, its bounty—called the second growth forest—offers regeneration following the destruction of the natural landscape, the displacement of its ecosystem. These blooms, emerging from scarred soil tilled for other vegetation, are the subject of LaKela Brown’s plaster still lifes included in Second Growth. Her harvest metaphorically suggests the miracle plants of Black America as it generates civic and community healing (its own Second Growth) after being “cleared” or separated from its original culture by the atrocities of colonialism and slavery. From the perspective of ethnobotany, these fruits also assert a Black American culinary tradition that is itself diasporic and migratory. Okra is indigenous to Africa; corn, native to the Americas, has been adapted into Black American cuisine. Though errantly evading a stable cultural categorization, these foods symbolize for Brown a shared constant of a Black American community––in which a meal emboldens a deep history, a collective effervescence.

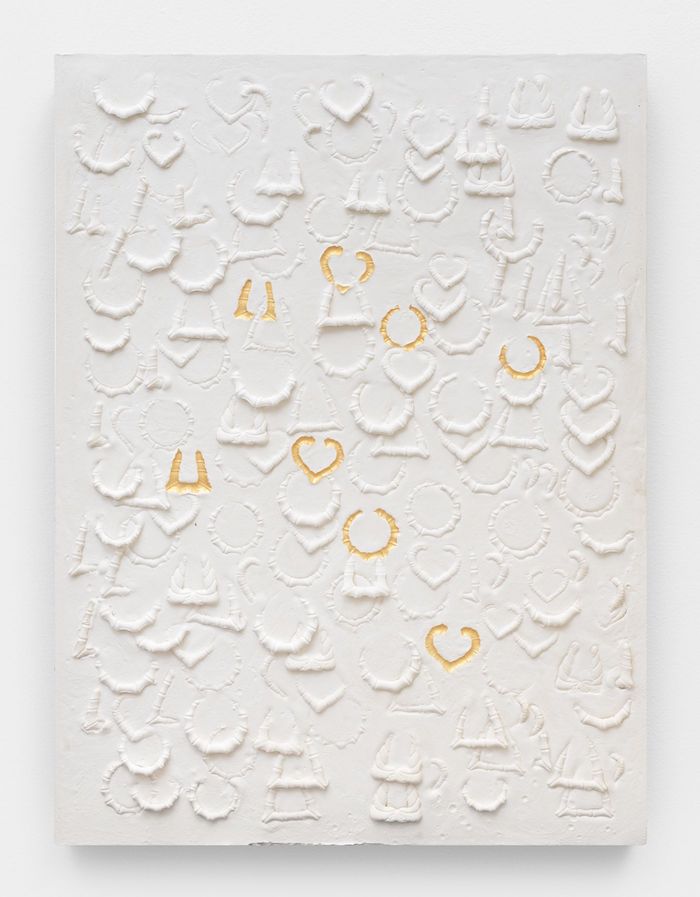

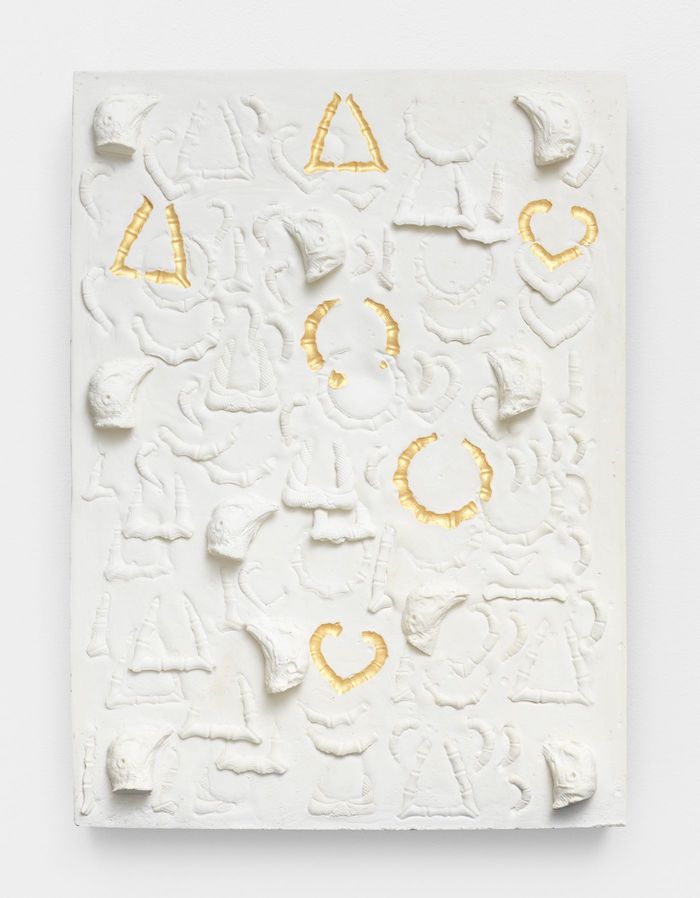

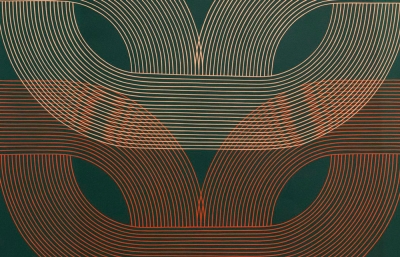

Also a second growth within the artist’s exploration of the relief technique, the new series marks an expansion in her visual vocabulary. Her earlier reliefs graft impressions and molds of door knocker earrings, bamboo hoops, gold teeth, thick chains: sumptuous symbols born from the visual culture of hip hop. In the exhibition, examples from this body of work provide a dense survey of hoop earring styles, plaster cast and displayed in relief. The otherwise monochrome compositions are punctuated by passages of gold, as if a residue of the metal jewelry was imprinted on the wet surface during the impression process.

Still attendant to objects of a distinctly Black imaginary, Brown’s still lifes propose objects that are culturally significant to her Black American experience as a rejoinder to the traditional subjects of the painterly genre. Here, the plant arrangements stand on their own or adhere to the wall architecturally. These arise from a dual impulse: a desire to subvert the subjects and arrangements of Western art (its prototypical genres, media, preoccupations) and a reevaluation of the false neutrality of architectural and visual language, which often occlude underlying psychosexual and gendered meanings. Brown contends with the truths of these objects: their roots and origins, modes of circulation, identity, instantiation of place, sense of belonging.

As with the jewelry bas reliefs, works such as African/American Still Life with Fruit No. 1 (Four Corn Stalks and Six Okras), motion to a body intentionally removed. Where dangling hoops pierce fleshy lobes, these foods are similarly ingested––marking a body changed but undisclosed. For Brown, sequestering the body is a protective gesture. The bodies to which the objects relate, Black bodies and more precisely those of Black women, are the site of representation that is predominantly contingent on the matrices of desire, sexuality, entertainment, and consumption. The artist further antagonizes a fetishistic formulation of her objects by providing an excess of the symbol. Assembling a concentrated aggregate of these cultural markers by repetitively casting and impressing, Brown emphasizes their connotative weight: at once ciphers of femininity, aspirational emblems, slivers of Black American adornment. Repetition also activates what the Martinique thinker Édouard Glissant theorizes as “an acknowledged form of consciousness here and elsewhere,” essentially reinstating the physical to resist dematerialization as stereotype or the diminishment of the Black body as spectacle or anonymous labor force and resource for what writer bell hooks has named the system of the white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

In this corporeal void, the viewer contends with objects of culture without escape to the body or other seductive palliatives. Ultimately, this amplifies the object as social signifier, symbol, polemic, and more. A packed relief comprised of chicken heads (brought back to the studio from discards at Roberta’s in Bushwick), for example, alludes both to a food culture and linguistic pun—“chickenhead” is a deprecatory term for a woman, playing on the bobbing motions of oral sex. The synecdochic chicken head is characteristic of the artist’s practice writ large: fragments of objects refer to shards of subcultures, which in turn represent a distinctly Black American experience. Marinating on these overlooked yet ubiquitous images, the artist actuates a volumetric approach to invisibility. By agingthese objects through her archaeological syntax of relief and relic, Brown excavates their abiding presence and power in the contemporary. —Megan Kincaid