Speaking about their creations in 2019, designers from the incubator 419 declared, “When people think of African fashion design, it’s always the same Dutch wax prints—which aren’t even African… and it’s not just about those long traditional caftans.” Given that a look at the continent is overdue, the Brooklyn Museum is expanding upon Africa Fashion from London’s V&A to showcase designers who emerged from the cultural revolution and those currently defining contemporary Africa. I spoke with curators Ernestine White-Mifetu and Annissa Malvoisin.

Gwynned Vitello: I was struck by a seemingly obvious statement by the V&A curator Christine Checinska, that Africa is a continent, not a country, “nor is African fashion a monoculture.”

Ernestine White-Mifetu: That’s true and very real in terms of the perception of the continent and its 54 countries. The exhibition is really an opportunity for us to expand on that and really provide the visitor with a kind of historical journey through the African continent and the respective countries’ process of obtaining emancipation. In addition, we included all of the countries and their flags, and in that, reiterate that it’s a continent with many diverse cultures and lived realities. So when you start off in the exhibition, the notion of Africa being a country is debunked.

Annissa Malvoisin: The show is all-encompassing, and you’ll see that expressed throughout the show, visible in each of the sections. Textile traditions are very diverse, depending on the region, and we made a point to highlight the different regionalities of each of those traditions in every aspect. You’ll see bògòlanfini from Mali, àdìrẹ and aṣọ-òkè from Nigeria, and Ndebele from South Africa, each unique in characteristics of these specific regions. For so long, the stereotypical trope of presenting Africa as a country with a singular aesthetic has been something we wanted to counteract with this show.

Ernestine: Christine Checinska and Elizabeth Murray did a really good job of highlighting this very fact that we are speaking about, that the show is about celebrating the diversity of African creativity through fashion, music, and visual arts. Throughout, via visual or other senses, you are involved with what it means for Africans to engage with themselves and the rest of the world, and its regionalities in a celebration of the continent on a global scale.

Can you explain why the show was called Africa Fashion as opposed to using the descriptor ‘African.’

Ernestine: It’s removing that trope of what is African as if Dashiki covers it all. Africa is the continent, but it’s also the world.

The flags are a compelling way to open the show, an impactful introduction to herald what’s coming.

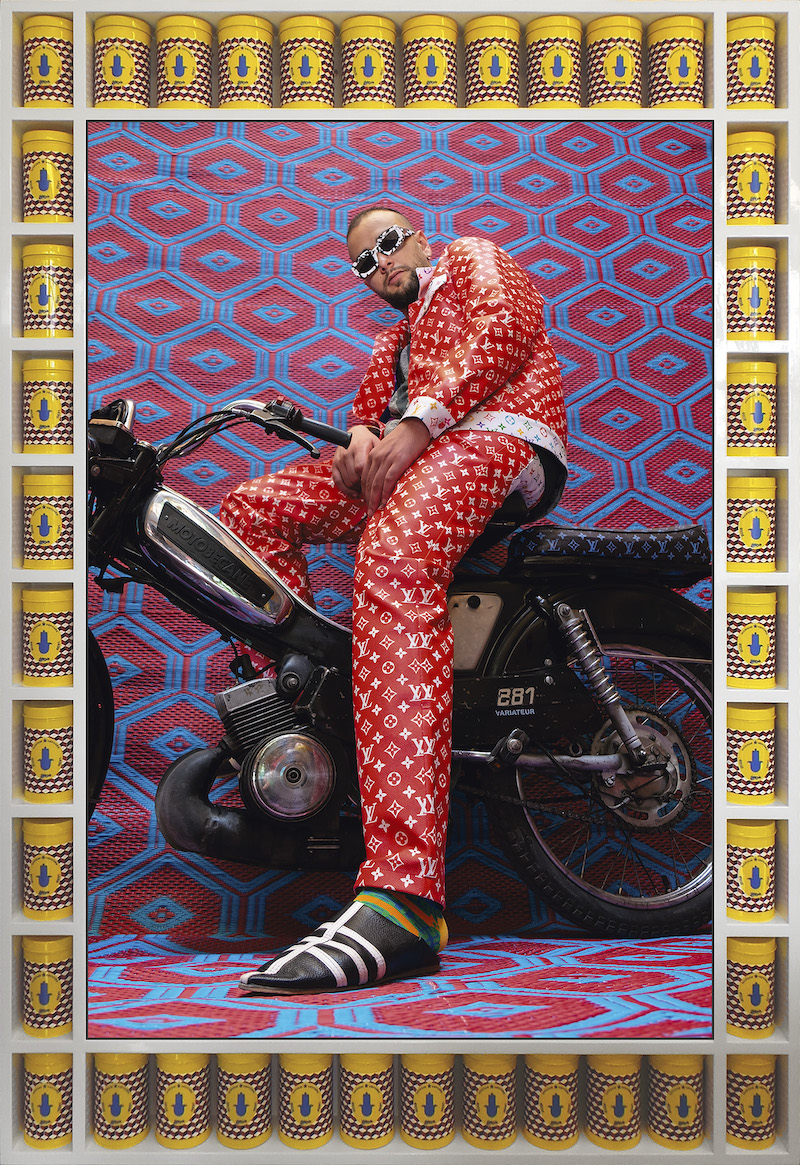

Ernestine: It’s always that way, that something can immediately attract you. I was waiting with bated breath for the stunning photograph by artist Trevor Stuurman. I had been waiting such a long time, and to finally see the work (this morning) in its physical manifestation was really exciting, especially getting to show the artist what his work looks like in conversation with the others, so that reaction was absolutely amazing. And similarly, with Maison ARTC, who is from Morocco. We literally just got on a video call and said, “Let’s show you what your stunning garment looks like in the space with so many other creatives from the continent.” His reaction was one of true gratitude and appreciation, but real excitement at being part of the conversation that engages the continent with the rest of the world.

I have to admit that I don’t know enough about the cultural revolution spurring the social and political changes that contributed to so much creativity and expression.

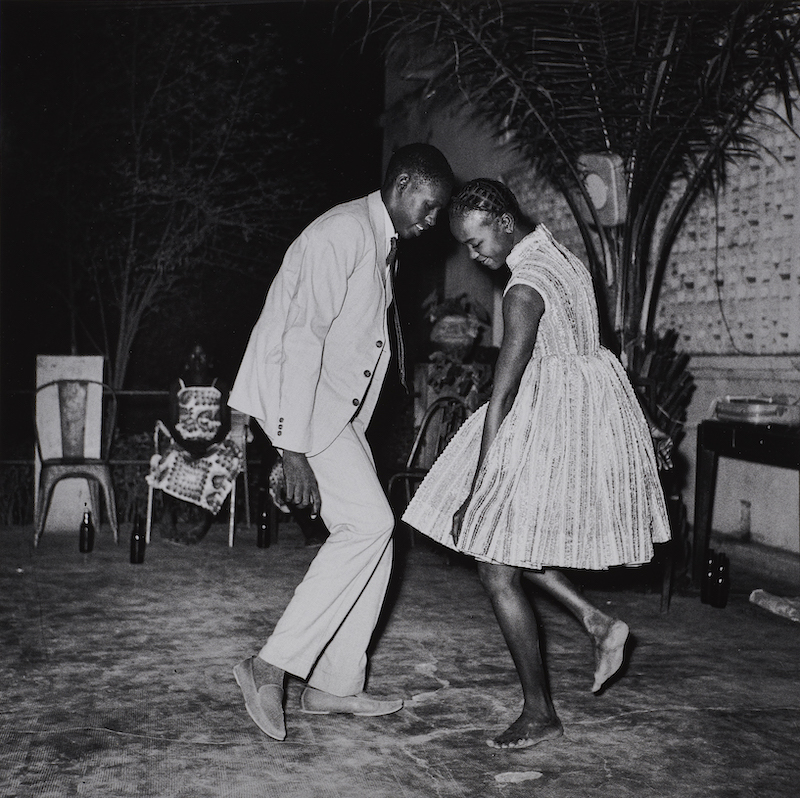

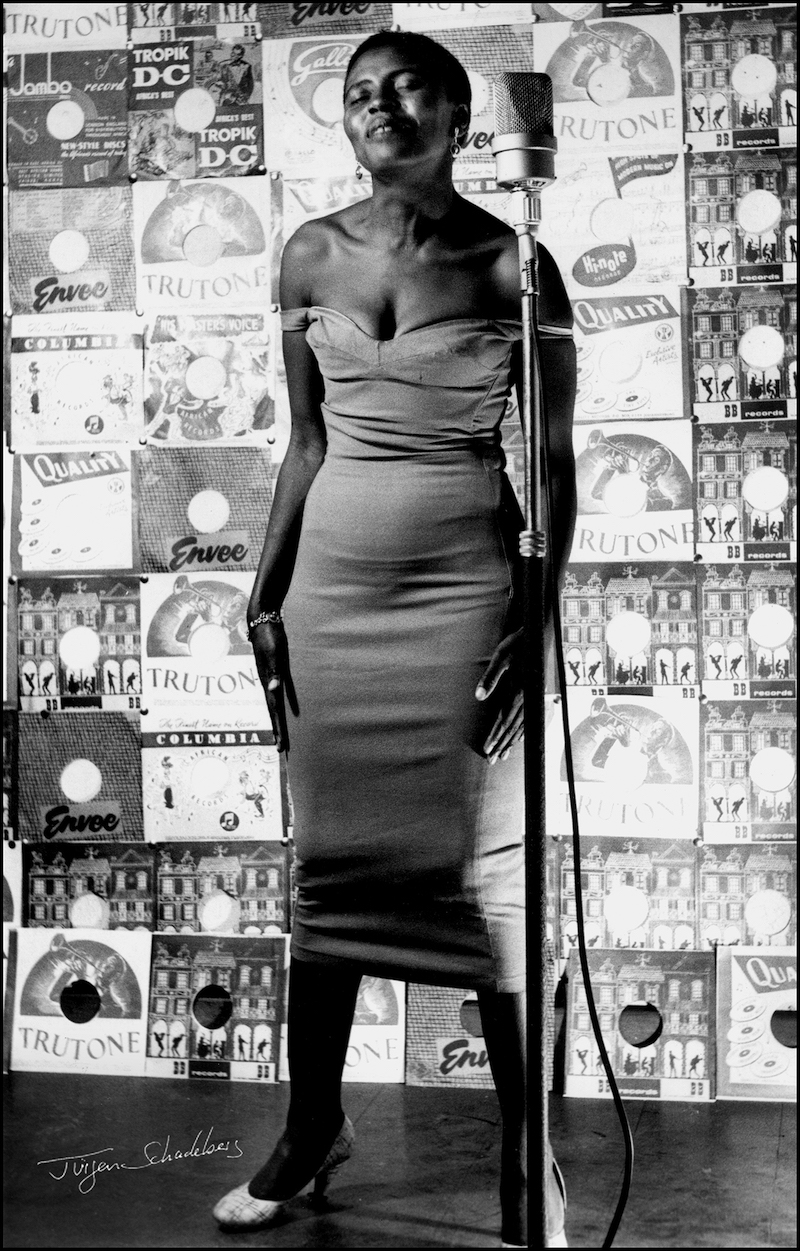

Ernestine: That section is called the Cultural Renaissance. Entering the exhibition, you get this timeline, the journey of all the African countries and their process of emancipation, and on the opposite side, you encounter Miriam Makeba, that iconic image you would see on the cover of Drum, along with some other images by the photographer Jurgen Schadeberg, who took the most famous images for the magazine. Further along, you encounter Fela Anikulapo Kuti in the section called Face Forward, where Africa is really fighting for independence. From Ghana’s 1957 independence to the present, we see an opportunity for the continent to understand what is possible, that freedom is possible. As that is happening, creatives are engaging with what it means to be in a space that is free to reimagine identity, through writers and musicians. These individuals were fearless in their activism, really engaging with this notion of decolonial thinking through music, voice, and sense of style. As you enter seeing Makeba and Fela, you move into a section that engages more with the notion of cultural renaissance, meeting the writers whose own visual expressions speak of the diverse languages, liberalities, and stories that are encapsulated in the one space.

And music has to play a huge part.

Ernestine: You can’t speak about this cultural revolution without music. You have a kind of compilation of album covers, some by Lemi Ghariokwu, the creator of some of Kuti’s album covers, as well as additional covers that engage with the notion of independence. There are also some beautiful vintage magazines from Drum, Jet, and Ebony. Again, popular culture addresses issues about poverty and struggle but also lived realities and celebrations. Photographers were an integral component of that conversation. One of the last sections gives a window into the festivals that celebrated the black and brown bodies through music, visual arts, and performance, as well as a peek through an online archive created by an organization called Panafest.

Annissa: Not only is this section a celebration, but it’s also a critique that looks back on the internal issues that occur within these regions. For example, with Fela and “Beasts of No Nation," he rejoices in being African, but also openly criticizes the Nigerian government for military and governmental transgressions on the population.

Let’s move into Fashion specifically. For some reason, I became kind of enchanted with Shade, so tell me about her before we move on to some of the others.

Annissa: Goodness, they are all amazing and beautiful, but I can specifically talk about Shade, who is such a great creator. Her work really encapsulates Nigerian women and includes fundamentals from her cultural heritage, so she uses traditional textiles from the Yorùbá (a large ethnic group in Nigeria) and she honors them and the techniques. She also modernized dressing to the point of pre-wrapping the gèlè headpiece, which is generally wrapped around the head so it could be easily put on.

Ernestine: For the bùbá and ìró, the top and bottom, which is really an art form that requires time-consuming folding, there she added zippers so it was “get up and go.” Shade created the kind of contemporary iteration of a traditional style for the young, modern woman.

Please introduce me to some other designers who caught your eye.

Annissa: I’m also intrigued by Nigerien designer Alphadi, who takes a real global approach to their work. Of Mauritanian descent, he was born in Mali and embodies an intercultural introspection through design. He utilizes different textile techniques and conceives amazing gowns, superstructured jackets, and mini-skirts. For example, he uses Kuba cloth from the Democratic Republic of Congo and also infuses the metalwork of the Tuareg, resulting in one piece we have, a stunning breastplate. And then we have Kofi Ansah, who has combined a European judge’s robe, a Japanese kimono, and a Yorùbá agbádá to create a whole new design.

So many of these historical designs are classic and could be worn today.

Ernestine: Exactly, and within this is a conversation about sustainability. This trend of slow fashion has been part of the African fashion ethos for centuries. The designers have chosen artisanal techniques that ensure they stand the test of time.

Annissa: The ancient textile traditions are maintained contemporarily so they never go out of style because they keep being reused and reimagined. They are very connected to their cultural heritage, so working with artisanal communities throughout the continent maintains the technique and modernity of the textiles.

The Cutting Edge section must be just that.

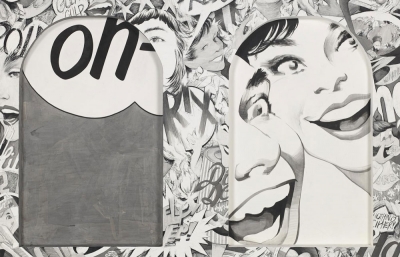

Ernestine: That’s where we start a conversation around the misconceptions of what Africa is. With the minimalists, for example, designers look at the creation of a garment that does not include a busy print, that focuses on a pared-down color in relation to the preconceptions of African fashion being this very colorful and diverse engagement with design. But we also have designers who do focus on the intricacies and busyness of textiles and design, really reimagining those understood tropes. And with Afrotopia we look at designers who are looking toward the future in terms of technology and new visual language.

There must be an area devoted to accessories.

Annissa: Oh yes! We have jewelry and headdresses, as well as expressions of hairstyles, actually, there’s an area where the emphasis is on the photographer’s engagement with hair. The section called Adornment looks at accessories as the statement, as almost the outfit itself.

How is the Brooklyn Museum presentation different from the Victoria and Albert exhibit?

Ernestine: Our is most certainly inspired by their vision, but we felt it was important to look at our lived reality here in North America and engage with communities who are here from the diaspora. How are we able to include them in this conversation about Africa? In the beginning, we include the African-American photographer Marilyn Nance, who is engaging with the continent, and later Kwame Braithwaite, an important photographer known for his contribution to the Black is Beautiful movement.

I know what I’ve been missing—music!

Annissa: Yes, Music was really, really important. We’ve chosen songs that relate very specifically to the time period and to what’s happening at the time within each section. It gives you this holistic experience and engagement with the objects, and we were able to expand to a multitude of regions of the continent. We’ve included Afrobeats, Amapiano, Chaabi music, Raï from Algeria and Morocco, Arab pop, Sudanese R&B and hip-hop, Angolan semba, and more. We wanted to make sure we represented the continent because, as we started out by saying, it’s a continent filled with different languages and customs.

I love that you appreciate how we have stressed the timelessness throughout, how the traditions are repeated and maintained throughout history. To quote the Moroccan artist Artsi Ifrah of Maison ARTC, “Without culture, we are naked.”

Africa Fashion is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through October 22, 2023 // This interview was originally published in our FALL 2023 Quarterly