A keen anticipation of travel is the opportunity to enjoy new experiences while learning the stories of cultures we’ve yet to meet. Local museums are often on the travel itinerary because they introduce us to a unique being as reflected in their home grown work of art. While physically boarding a plane or filling a tank of gas is still a challenge, there’s every opportunity to to travel by looking at art. And so, we invite you to meet the Ethiopian Jewish population that has become an expansive presence in Israel, the product of two large movements in the 1980s and 90s, though, in fact, this Israel-Ethiopia connection actually spans several millennia—with members of Beta Israel believed to have emigrated to Ethiopia from ancient Israel in the first and sixth centuries.

Though some were forcibly converted to Christianity in the centuries that followed, a significant portion of this community maintained traditions, remaining steadfast in their Jewish faith. This served the thousands of Ethiopian Jews who returned to Israel in the 20th century quite well, as the current Israeli Ethiopian community consists of more than 140,000 members. Many of them are artists who play a prominent role in Israeli culture and society.

November 21, 1984, marked the beginning of a seven-week clandestine mission that would bring over 8,000 Ethiopian Jews to Israel over the course of 30-some flights, in a movement known as Operation Moses. The covert operation rescued Ethiopian Jews in Sudanese refugee camps from anti-Semitic persecution.

Circumstances had become so dire that people traveled through the region’s deserts, where they would ultimately meet Israeli workers before flying to safety. The operation continued until January 5 1985, when the international media became cognizant of the movement.

This wasn’t the end of Ethiopian Jews’ migration to Israel. Another 14,300 Ethiopian Jews were airlifted from Addis Ababa to Israel on May 23, 1991, in response to the nation’s civil war and impending famine. Diplomats negotiated a last-minute agreement with the Ethiopian government, and members of the Jewish faith were rescued just days before Addis Ababa fell to rebel forces. 35 aircraft were involved in the short-term mission, which was so time-sensitive that one plane still holds the Guinness World Record for most passengers on a single flight. The aircraft in question transported 1,078 people to safety, with two additional passengers born onboard. Both operations brought remarkable artistic talent to Israel.

In 2021, estimates reveal that roughly 100 or so Jews remain in Ethiopia today, yet culturally, Ethiopian Judaism thrives. The five artists profiled below strive to honor their respective collective histories while acknowledging the path forward.

Tigist Yoseph Ron

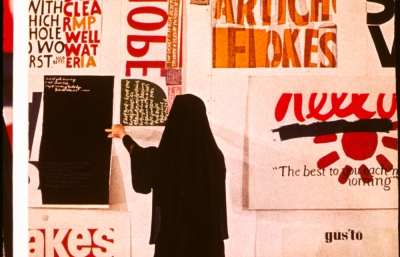

Soft and simple, Tigist Yoseph Ron believes working in black and white helps her focus on the emotions present in her visual stories. Femininity, motherhood, and a sense of otherness—of feeling foreign following displacement, or in the wake of transition—create a sense of rhythm; the social commentary Ron creates by showcasing everyday activities and tasks is palpable. Generally, the artist begins each work with a person to whom she is close, respecting the person’s privacy by shadowing the face, as she delves further. Each drawing remains special to her, an experience driven by the physical experience of applying natural charcoal directly onto paper. “The whole body participates in the creation,” Ron explains. “The physicality of the work and the direct contact make it more human, natural, and real to me.”

While there’s movement in the process of creating, the viewer experiences a similar fluidity. Ron has learned that long lines moving in a certain direction can help guide the viewer’s eye across the page, creating a rhythm via shapes and abstractions. This adds depth to the work, fostering a greater sense of connection between creator and viewer—an effect that will be apparent in the artist’s upcoming Home series, featuring drawings that will be on view in Rome and Tel Aviv in the late spring.

Nirit Takele

Nirit Takele does not remember much of her journey to Israel in 1991. Yet a single snapshot is lodged in her mind like a freeze frame, the image of her family’s journey from a village called Konzala, on their way to Addis Ababa, where they would flee Ethiopia as part of Operation Solomon. She has carried this experience with her over the years, though the Tel Aviv-based artist admits she referred to her experience only once during her art studies at Shenkar College of Engineering in Design, where she earned her BFA in 2015.

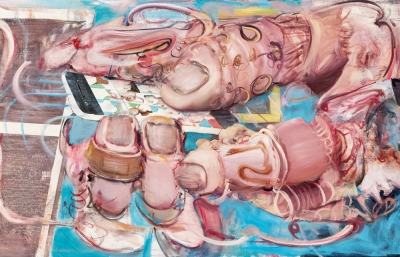

While the physical transition that Ethiopian Jews made to Israel isn’t visible in her work—not from the outside—the artist’s cultural heritage is apparent. Takele’s vibrant paintings depict the reality of life for Ethiopian Jews in Israel today, the impact of finding familiarity in the unfamiliar. “I am referring to the movement that takes place during the painting process,” the artist explains.

This evolution, as Takele describes it, results directly from the brush. It comes from smearing paint on the broad surface of a large canvas, which allows for a large and flowing rhythm. Simultaneously, there is movement in the painting itself, as body poses convey the act of reaching for something, the shift of a leg, or perhaps the decision to touch another person or rest a head on another’s shoulder. Takele’s subjects are consistently interacting with one another, or else finding synchronicity themselves, arms and legs spanning the canvases to evoke activity, or to eye contact with another being.

Michal Mamit Worke

Michal Mamit Worke immigrated to Israel at the age of three on Operation Moses. The transition seemed merely physical—Worke does not remember leaving Ethiopia—but it has since come to shape her entire life. Today the figurative painter lives and works in Tel Aviv, and she now recognizes that migrating across continents with minimal recollection of the specifics still amounts to a transformative experience. The artist’s mother remembers the journey well and regularly told her daughter stories, helping to recreate each moment piece by piece.

It was a 2021 residency in Addis Ababa, however, that brought things into perspective for the Ethiopian Israeli painter. Worke felt free and liberated, after returning to her roots—and this marked a turning point in her career. Everything changed after, she explains, right down to her use of color. While there was something very clean in Worke’s early paintings, she now feels confidence in how her hand moves more seamlessly.

With this new and broader color palette, Worke’s stylized paintings continue to feature scenes and people from the normal day to day—toeing the line between figurative and realistic painting in their composition. Yet now the paintings acknowledge the artist’s heritage in a fuller new fashion, incorporating Ethiopian objects and traditions in the scenes depicted on each canvas.

“The movement within my art is mostly reflected in the composition of the painting,” says the artist. “I tend to portray people in their natural positions and movements. They come to the studio, we talk, and they choose the position they feel the most comfortable in.”

Ephraim Wasse

A photographer living in Haifa’s Kiryat Yam, Ephraim Wasse believes art should play a vital role in everyday cultural experience. The child of Ethiopian parents, his upbringing lacked any significant exposure to the arts—and Wasse has since made a point of bringing art directly to the masses. Young people, in particular, he feels, have grown disconnected from older generations, and art can help them reconnect.

Achieving this isn’t without challenges. Wasse took a break from creating for a short time, stepping away to understand his place in the arts, to evaluate what he brings to the table, and ultimately, to decide whether he wants to continue pursuing photography. Early in 2022, he reconnected with artists who inspire him and, once again, feels the pull to create—exploring themes ranging from Black bodies and Ethiopian culture (both from a queer angle) to boundaries between the sexes. Movement is apparent throughout, including in the three stills that make up Wasse’s SKIN series, where motion is integral to the near-sculptural experience he creates. Close-up images of twisted torsos and extended arms create a figurative effect, showcasing the fluid power of the human body in a way that’s entirely his own.

“I like to play with motion when it contributes to the image,” says Wasse, who believes effects like blurring contribute more to the illusion of motion than they do the real object. His experimental approach is founded on immobility and the unexpected, applying sharp angles and calculated poses that redefine the way viewers experience their own physicality.

Shimon Wanda

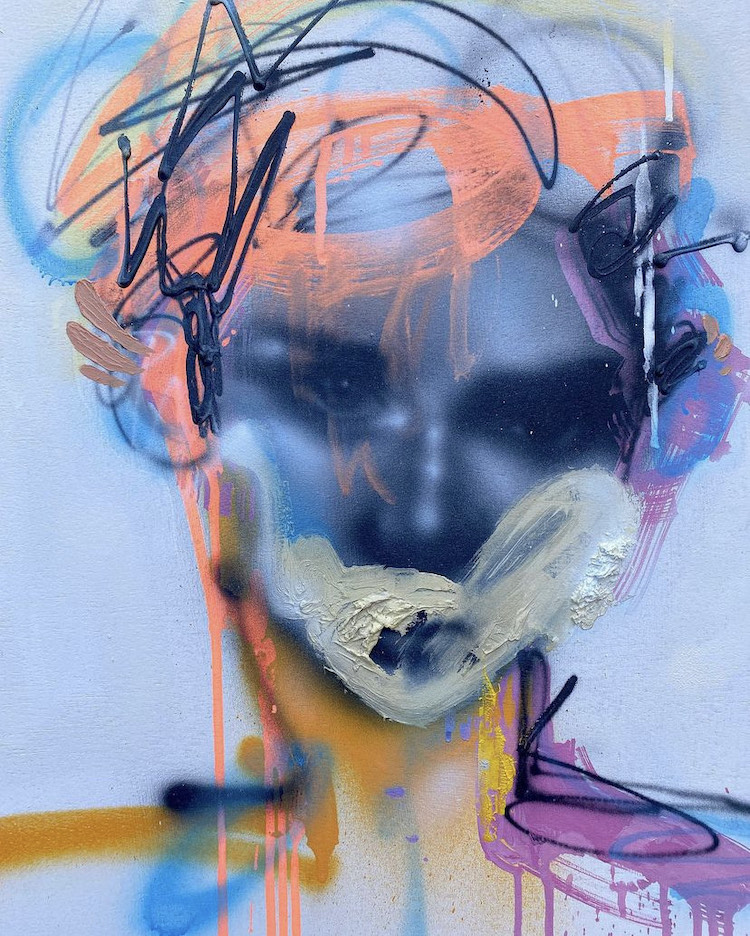

Shimon Wanda is a multidisciplinary contemporary artist from Haifa’s Kiryat Haim neighborhood. Born in Israel, his influence is nonetheless founded on the history of Ethiopian migration to Israel—shaped through his parents’ experience, for whom escaping Ethiopia was not easy. The artist takes an experimental approach, completing a blend of large murals and smaller portraits, and more recently, applying spray paint to convey movement and emotion in real time.

Wanda’s work asks questions about Ethiopian Jewish culture, often by way of vibrant neon colors and abstracted shapes. His artistry is specific, visibly his own, yet constantly evolving—currently focusing on intuition and inquiry, and moving away from careful planning to tell his subjects’ stories. “My choice to convey emotions through the expression of the portrait involves a state of freeze,” says the artist. “But on the other hand, I want to make the viewer confused and excited.”

The artist maintains a strict training regimen involving his upper body and hand movements, working hard to increase flexibility and fluidity while reducing the risk of confronting his greatest fear of no longer being able to paint.

text and research by Charles Moore // This article was originally published in the Summer 2022 Quarterly