Artist Donald Bradford returns to Andrea Schwartz Gallery after a five year hiatus, for his 3rd solo exhibition there. The exhibition “Lazarus Paintings” showcases a selection of 13 paintings from a larger body of work revolving around themes of loss and rebirth – the through line viewers will no doubt register. Many of the paintings are anchored in narratives that serve as foundation myths, meaning they pertain to a collective cultural consciousness, and as such Bradford’s paintings intuitively feel closer to us, even immediate.

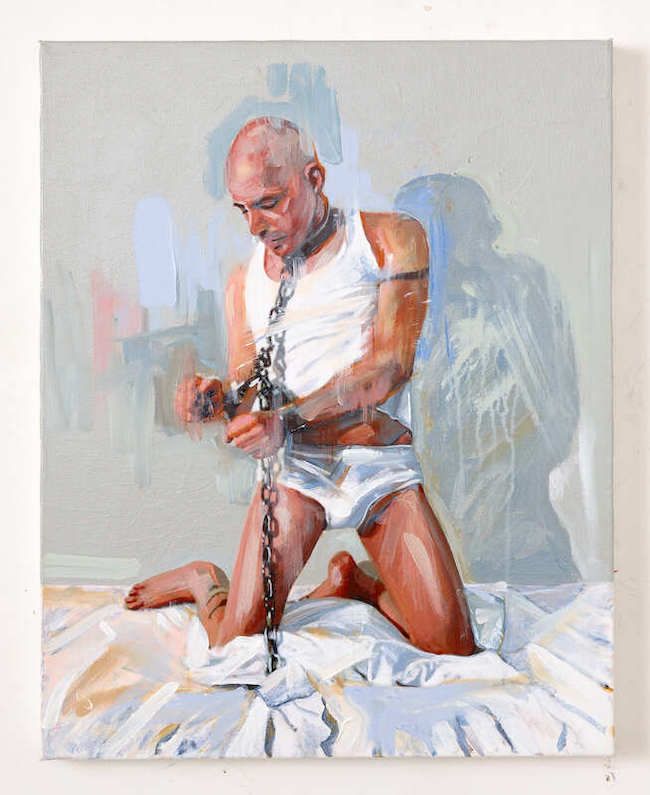

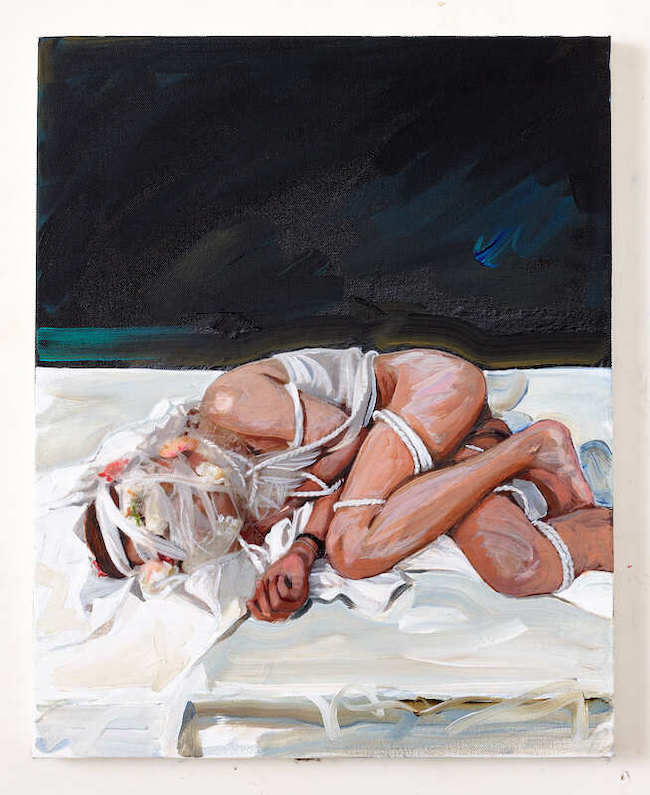

Bradford has returned to some of his earlier painting work to recast former models, many are friends or acquaintances whom he has painted in the past 40 years. Although he primarily relies on live models he poses in his Oakland studio, this return to familiar subjects heightens the presentation of narratives pertaining to historical and biblical personas such as Saint Sebastian, Madame Butterfly, Prometheus, and Lazarus; the latter who famously rose to life four days after his death. The burden of history emerges as a substratum and underscores the way the archetype narratives anchor each of our lives. Though quite personal, the viewer’s ability to recognize these myths and stories, albeit not the particular models, abuts Bradford’s painterly sensibilities which ultimately carries the day.

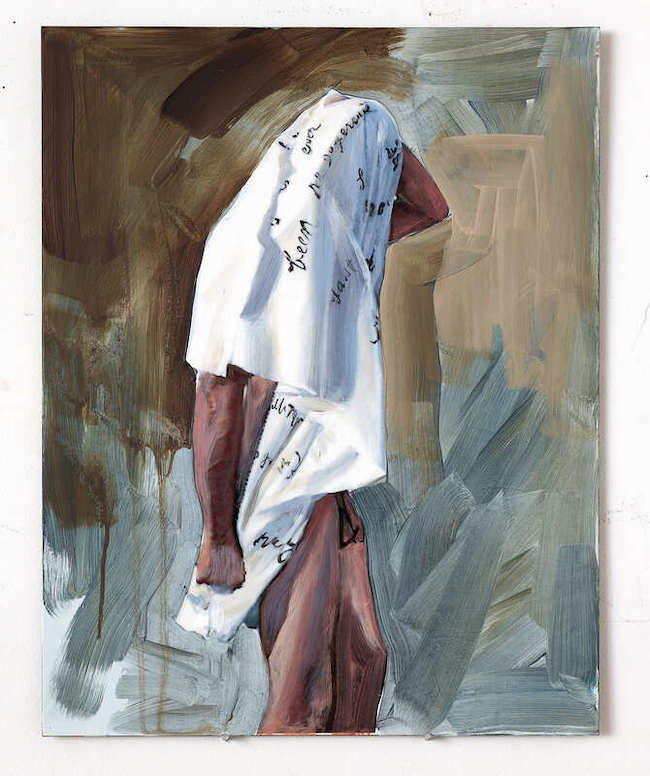

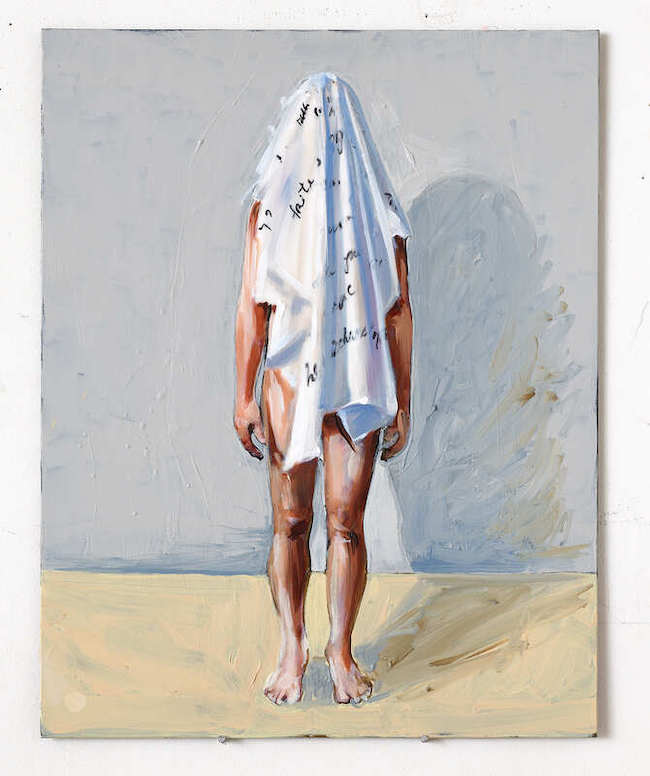

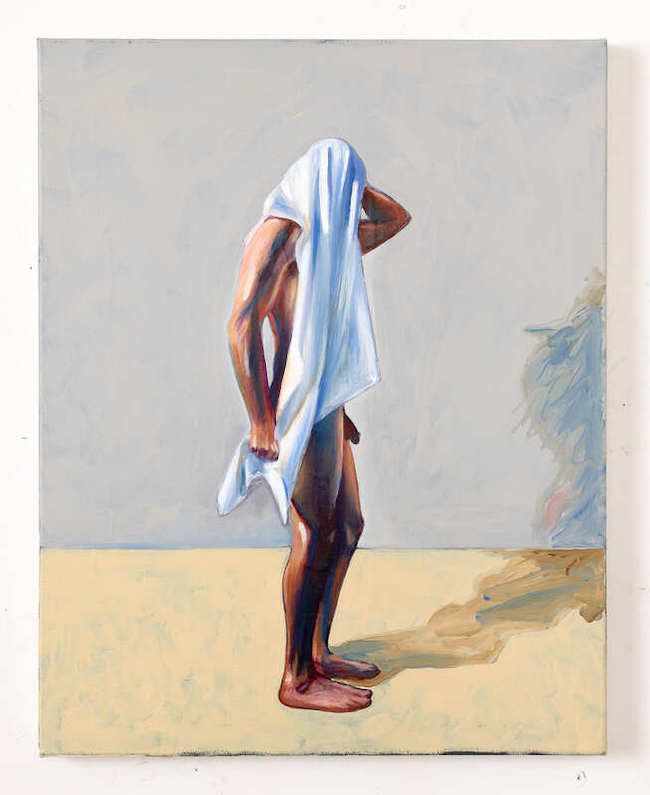

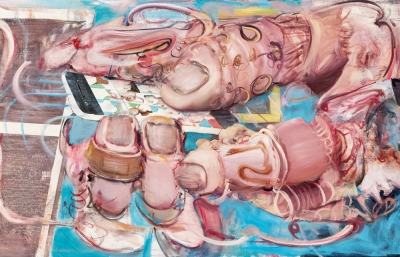

Mining such well-known narratives can pose challenges. Do you stifle creativity by relying on worn paths and how do you keep the final pictures from resembling cliches given their repetition over hundreds of years? While these pitfalls could threaten to impose themselves here, Bradford eludes them because the thematic element primarily exists as a frame from which to show off his painterly skills. Yes, whatever drama is unfolding is notable, but it is the rendering of paint that excites. No doubt some viewers will first be drawn to the mixing of stories with recurring bondage subject matter and male nudity explicit throughout the show, but this focus is the starting place for viewers to engage with how Bradford makes his paintings. When David Park painted a sink or Diebenkorn scissors and a lemon, it wasn’t any more about the well known subject matter, in these cases the mundane, that viewers were fascinated with but rather the application of a style. Bradford utilizes improvisational paint application, a collage approach, and he is particularly good at rendering flesh tones and fabric folds within the array of expressionist marks. Their role in these paintings helps balance the compositional forces at play within them, which would otherwise only favor human figurative elements. Furthermore, these elements, such as the convolution of clothing, which appears in various canvases, suggests the haphazard ways life unfolds, thus allowing Bradford to intertwine these elements with the exhibition's larger theme of renewal.

In essence, Bradford’s method is to begin the painting in a tight realistic style and thereafter obliterate the literalness as he works toward a looser expressionism. By doing so he brings the paintings closer to capturing an immediate direct experience. To render it strictly realistically would neglect elements of movement, the very essence of a pulsation force; one needed to add vibrancy to the work and more importantly, to accurately depict life. His painting rhythm is analogous to a cadence in speech; once you’ve acclimated to his method, you hear the melody. The act of obliterating the realism, in effect, messing them up, is how he pushes them toward their end. Unlike painters who work by tightening up an initial, loose pass, Bradford does the opposite which ensures the capturing of a quality pitted against inertia. This ultimately focuses and defines his pertinent gaze.

Although not a collage artist, per se, his method resembles collage as he overlaps marks and sometimes compartmentalizes the canvas. The very smooshing of paint, over the underpaint, which creates expressionist marks, obscures a truth that he can paint with precision but purposely comments on how that would leave behind an essential detail of realism – the aura of movement and breath. His looseness evokes a freshness – as if he’s upcycling or repurposing, allowing the viewer to get something more dynamic than a staid brush mark. Bradford’s method is arguably more realistic because of the enrichment of ambiguity that neighbors the sentient quality of the here and now. The looser element works as an aura – an aura of gesture and emotion.

Bradford’s color handling is one of his reliable strengths. It’s refreshing to see even the neutral elements of the canvas given close attention. Rather than treating those areas as shadows or a background lacking a focal point, Bradford mixes paints, a deep violet background for instance, keeping an over pigmented quality from overtaking those areas. This intentionality envelopes the foreground of the paintings making it seem as if it’s pushing the subject matter off the canvas. This works particularly well with the Lazarus themes of rebirthing, a kind of shamanist consciousness, where a subject can take a new form. The neutral colors aren’t presented by what they lack – light, but rather by what they include, elements of colors playing a larger role elsewhere. This unifying effect highlights the figurative elements in the composition.

It is worth noting Bradford's past engagement with performance art, particularly during his graduate studies at U.C. Santa Barbara is revelatory, as the body and movement are primary concerns with the two-dimensional canvas. He studied dance and choreography thus grounding him in the essential qualities of our essence and now grapples with presenting them on the painted canvas. These elemental things, activity and time, get presented heightening the theatrical figures he poses. Because Bradford usually works from life observation, the paintings have both a staged quality and the excitement of approximating animation.

Bradford’s paintings have rhythm, a strong design element, and narrative elements that work beneath, and in front of, expressionist gestural paint. He utilizes a style that surpasses a strictly formal figuration, thus succeeding in breathing life into an otherwise quiescent medium. —Matt Gonzalez