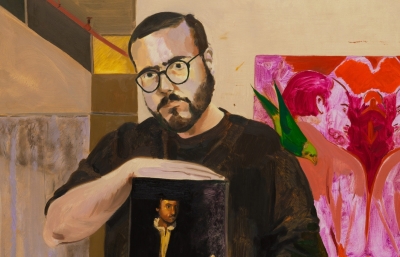

Anthony Cudahy

The Inflections of Somebody

Interview by Evan Pricco // Portrait by Daniel Terna

It begins with a space. The original, creaking floors of GRIMM's Tribeca space brings out something special in the viewing of Anthony Cudahy’s paintings, a show I wanted to see before speaking with the artist on the brink of another show, his museum show, Spinneret, opening at the Green Family Art Foundation this fall. Cudahy paints emotion and something quite moody, and when you circle the gallery, the timeworn floorboards enhance the intimacy of the works on view, evoking an intimate sigh as you find yourself quietly trying not to disturb the characters, not quite sure if you should be privy to what is happening in the scenes around you.

Cudahy is in reflection when we speak, an artist who is painting parts of himself, his husband and his friends that become a full narrative, sweeping across numerous shows and venues in America. What we spoke about is those bursts of creativity, the ability to improv, and the influences that shook him and changed his perspective on how to paint, as he connects to his peers with paintings that are contagious.

Evan Pricco: How are things? You had fall openings with concurrent solo shows in NYC with GRIMM and Hales, and there was the museum show at Ogunquit Museum of American Art in Maine early this year that is now traveling to the Green Family Art Foundation in Dallas, so it's been quite a busy time. How are you feeling now? What's Anthony's mindset right now, as I see you smile…

Anthony Cudahy: This past week, it felt like I was getting back into a normal routine or swing of things. I finished a few works. This year there were big deadlines and I was, despite my best efforts, working right up to the end. So I haven't been in the studio, really, for a month and a half, which is really unusual for me. And then I just finally got to go around Tribeca to see my friends' shows and other people's shows that are up right now. I feel like I'm getting back into a normal state. It will never not be strange to me, and I talk about this with some of my other friends who are painters, to just be completely alone and solitary for several months; then when you are social again, it's with so many people that it's a really intense environment, like going from one extreme to another. So I feel like I need time after that to recoup.

When you have so many deadlines, does time accelerate or slow down?

Maybe a little bit of both, and sometimes that's good. Sometimes you're super present in the studio and you are painting for 10 hours and it feels like nothing; you're really, really present and just doing the thing that you would most like to be doing. It's also a little strange. There's the shows that are open right now that I've known about or scheduled or planned for a long time, and there were a bunch of other projects this year that we were working on for several years, and they all just happened. So I have had a weird sense of time this year, because there are certain things that have always been, in my head, far off into the future, that have now exhibited or come out. And so now I'm on the other side of that, and it feels a little strange.

Maybe this seems like an odd question, but how present do you actually want to be in the studio?

I'll probably say this 80 times for this interview, but I really like my work to always be kind of in between two things. I feel like I set up a lot of parameters for the paintings. Like I might make a collage first as the basis for the drawing, or I might do a really rudimentary color map of what I'm planning in my head. But then that gives me the freedom to improv, or push off against it.

Maybe earlier on in your career, you're a little bit more precious with your paintings, but at a certain point, I know that if I don't risk ruining it or if I don't push it in a different way or try something new, I'm not going to be satisfied. So, to answer your question, I think I like having the structure and a plan, and then really being able to improvise and completely flip it up, changing it for the sake of the painting and not be worried about editing or ruining something that worked.

There is a way that being super present might make you self-conscious. That might be overthinking. But I think I'm trying to get to that flow state, which I feel is the opposite of being hyper-fixated on things that aren't happening right. I don't want to be present in the sense that I'm so worried about where the painting is going to end up, but I want to be present in the sense that I'm on that certain wavelength, just that perfect feeling when you're painting.

Anthony, what are you painting?

I don't even know if it's a tightrope or if it's between two things, because to me it is very, very personal. In terms of the paintings and things I'm interested in, and the themes and the symbols, I could provide an annotated guide for reading them and how it would relate to my particular vantage point, place and time. But also I'm interested in the conventions of narrative and of figurative painting in general. It's how we organize meaning and tell stories, and that all has the macro-micro thing, where I think the more intensely personal and specific you are, the more you can latch onto something that a lot of people relate to.

I feel like the paintings are concerned with the very general big issues that people have always been concerned with: mortality and legacy, and wanting to know another person and wanting to be known. Within that, I'm interested in painting as a language where there are conventions and belief systems around it that people have. Like, “This portrait reveals some inner truth about the sitter.” I think it's just that I'm very interested in figurative and narrative art.

I wrote about your work and the GRIMM show in particular. I had this idea, this feeling, because when you went into the gallery, there were these creaky floors—aged, hundred year old wooden floors. I was the only one in the gallery at first, and kind of felt like I was imposing on the characters as they were in a really personal moment. As the floors were creaking as I was going near the paintings, I felt like I was ruining the character’s moment, or I was trying subconsciously not to be heard. It was a haunting experience, wonderful, really. It felt so right. I like that idea of wanting to be seen and wanting other people to see you, but also the things that we don't share, and how much, when we engage in relationships. I love that this feeling is so palpable in your work.

For me or for somebody who is shy and maybe not extroverted, it's kind of lovely to have these proxy objects that almost get to stand in for you.

This is something that I think about with a painting practice—repeating figures like my husband or myself, or other people that recur, sometimes represents this one aspect of themselves, sometimes much more straightforward, almost an observational portrait, and sometimes they're playing a character, or it's more allegorical. I've painted my husband Ian probably hundreds of times at this point. Each part of it is an aspect of this person. The more straightforward ones that read as intimate might not be as truthful as one that’s more set up, more cinemagraphic, an allegorical painting. Him playing a character might be more truthful to the life events or symbols that I'm trying to work through in the painting.

Similarly, I feel as if each painting is a proxy object for me, a chance to share or withhold something about myself. That also is a part of the narrative that I'm interested in. I'm interested in the vantage point, how knowledge of the author can impact the narrative or reading of a painting.

What kind of responsibility do you feel painting your husband this many times?

The only real responsibility I feel is that he's a photographer, and I never say no to an idea that he has with me. I feel that with anybody that I paint, if they have an art practice and they want to involve me in some way, I feel that you can't really ask someone to do all of this if you're not also willing to be in the same position, even if it makes you uncomfortable. I know that even with someone that you are maybe the closest to in the world, there's still a barrier. You still don't a hundred percent know them. So I don't feel like it's a responsibility to accurately portray something of his character. I feel like I am just there to record their inflections, and maybe over time in a body of work, that can all add up to a picture of someone. But I feel like with the individual ones, it’s either a moment in time or it's a character.

What was the first moment where you saw an artistic language that moved you?

I feel like there's several moments, probably in art books, first. I grew up in Fort Myers, Florida, and one of the nearest venues was the Dalí Museum in St. Pete. I would go there with my mom sometimes. And when I was a teenager, finding out that Lucian Freud or Jenny Saville were living, contemporary artists kind of blew my mind. I always wanted to paint, but on some level, I considered it an act from the past that people didn't currently do except as a hobby.

Later on, when I was already painting for a little while, there was the New Museum retrospective of Chris Ofili. I was depressed for months after seeing it because it completely rearranged what kind of work I could imagine as possible to make, but something I wanted to make. I was so in awe of those paintings, and they just really rocked my universe. I think that had a profound impact. So this and finding Lucian Freud when I was a teenager also had a huge impact on how I thought about painting or how I wanted to paint.

You realize you just named three British painters.

I think it’s just dependent on where really good figurative painting that I'm responding to is at a time. There were definitely moments when London was the place for that, and there were so many amazing artists like Bacon and Hockney. I think sometimes there are just groups that happen, like Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner and Grace Hartigan in NYC. There's just moments when it seems like the paintings are sort of contagious with each other.

That’s such a brilliant way to say it. Obviously there are the ebbs and flows of figurative art, but as you're talking about these groups, these infectious moments where there's just a group of painters who are in conversation with each other, I wonder who you think you are in conversation with?

Before the art world was interested in queer figurative art, for lack of a better word, a lot of us had already been friends or had found each other online. It was just this amazing experience of finding like-minded people who also believed in painting and believed in figurative work in a way that just really harmonized with what we all happened to be doing. And so a lot of these people with whom you might end up being lumped together are people who I have been friends with for a really long time. So that's a really beautiful thing.

I’m thinking of artists like Jenna Gribbon. We met at Hunter when we were both there. Around 2012, Robin F. Williams reached out when she moved here after grad school; she was so friendly. And finding out about Doron Langberg from his Tumblr, and then when he moved to New York, reaching out to interview him for a project I was doing, it eventually ends up being people that you've now known for over a decade. I do think that, especially when nobody was looking at what we were doing, there must have been many instances of each person figuring out their individual project, and we were watching each other at the same time.

You had this explosion of people knowing your work at the latter part of the pandemic, a wider audience, I should say. So was the pandemic a fruitful time for you?

It was, in retrospect, a very good thing for me. I lost access to my studio, and so it was the first time in my adult life that I didn't paint for a long period of time. I actually had a lot of space to think about what I wanted from my work and where I wanted to push it. My work changed a lot immediately after that and has been in flux since then. I just had this moment where I could take a step back and see the work without being so close to it, where you can't see what's going on. I've always felt like if you look at painters' practices across the years, there's usually a few ideas or scenes they're drawn to again and again. And so I feel like I had a little bit of an out-of-body seeing what that was for me, and then thinking more about, "How can I push the work to make that more clear?” It really was just a complete top-down reevaluation.

As we speak, you will be traveling this week to see your museum show, Spinneret, travel to Dallas from Maine. Do you get nervous thinking about seeing the work again, in a new context, in a new place?

It makes me think, before the first show of Spinneret at the Ogunquit Museum, I went up to see the installation; approve of everything. And I was extremely nervous to see all the paintings again. I don't know why, really, but there's a couple levels of, "What if they're falling apart somehow?" or "What if I really just don't feel like it holds up as an in-person painting?" It ended up being a great experience, because there was this level of just distance, to appreciate them for different reasons, even certain ways that it brought back these bodily memories of making it. So I'm way less worried this time, to have all this work that I did over the years, in some cases, get a second chance to be viewed.

Anthony Cudahy: Spinneret will be on view at the Green Family Art Foundation in Dallas through January 26, 2025. This interview was originally published in our WINTER 2025 Quarterly.