Kustom Kulture

Auto-Didactic: the Juxtapoz School at the Petersen Automotive Museum

Interview by Gwynned Vitello // Portrait by David Broach

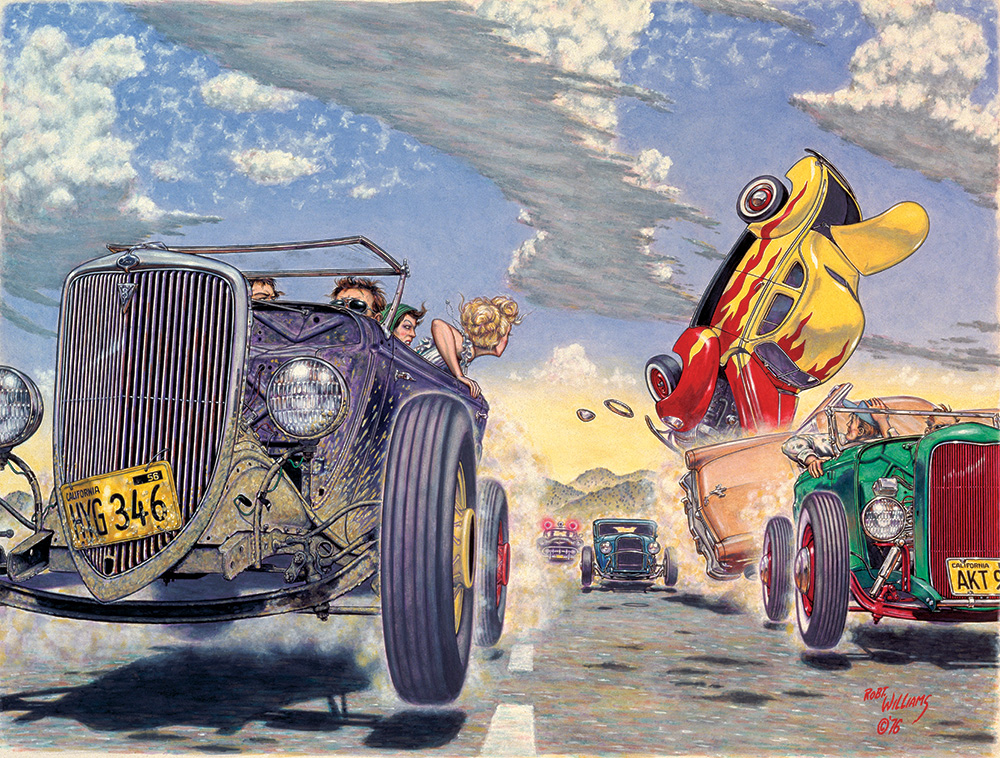

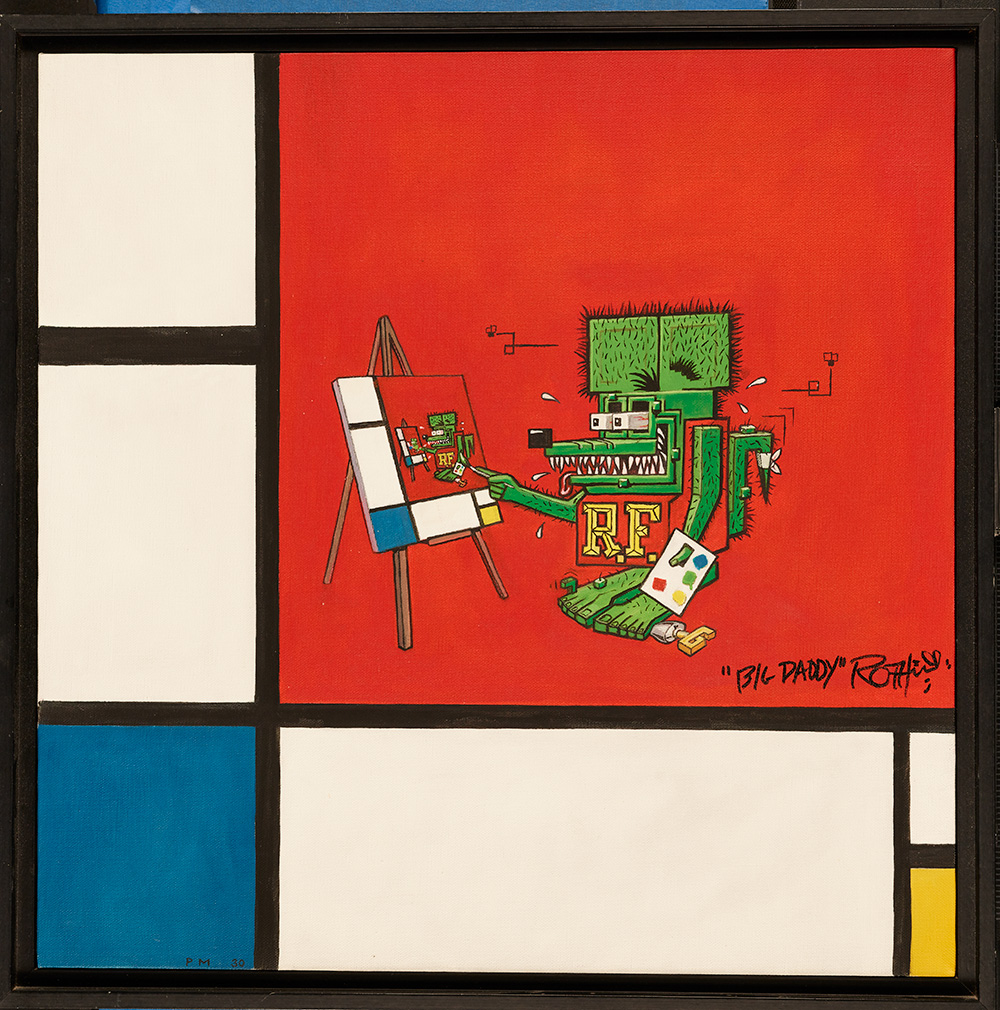

If film actors aren’t crashing an automobile, they’re slamming the door or moodily staring out the windshield. Behind the steering wheel, a day is defined with determination, an evening relinquished in resignation. As vehicles roar and hum outside, each with a story, I think of creatives like Von Dutch and Big Daddy Roth, who celebrated their cars with speed and sass. Brash, funny—and, yes, it was art, leading Robert Williams, whose Rubberneck Manifesto declared, “it isn’t what you like, it’s what the fuck you want to see,” to start Juxtapoz. On September 29, 2018 Auto-Didactic: the Juxtapoz School opens at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, co-curated by art historian Joseph Harper, currently Assistant Curator at the Petersen and sooth/cypher Craig Stecyk, who selected the works and defined Kustom Kulture for the Laguna Museum in 1993. Each shared their prescient perspectives.

Gwynned Vitello: In your Kustom Kulture essay, Craig, you describe the 1992 Rat Fink Reunion as street theater, a gathering of filmmakers, welders and artists. I think newer readers would like to know how the first Kustom Kulture show came about in 1993.

Craig Stecyk: Numerous principals were preparing for the show, and Susan Anderson tossed out the words custom and culture, ensuing further spirited discussion. We all agreed to streamline its spelling by using K’s. This was done in homage to the period theatrics of George Barris, King of the kustomizers Greg Escalante later observed that “the show both created the term and validated a new movement.” The twentieth anniversary Kustom Kulture II was held at the Huntington Beach Art Center in the summer of 2014 during the run of the US Open of Surfing. Over one million people came through this super-charged proposition of renegade art forms. Bronzed resort couture met urban street wear as the high surf washed over pinnacle culture. The loosely knit organization that came to found Juxtapoz was greatly informed by Kustom Kulture. In 1988, L.E. Coleman had written a piece on Robert for an art journal, and I had shot photos and participated in the interview sessions. The publisher refused to run it, citing its “inherent offensive content,” but Fausto Vitello and Eric Swenson, who were visiting Coleman’s studio at the time, became aware of the piece and offered to print it in Thrasher. It appeared 100% intact as a cover story, and when Escalante saw it, he asked me to introduce him to Robert. The plot thickened. Motive, opportunity and desire to create a relevant cultural mag emerged, and thirty years later, that, in turn, led to this survey show at the Petersen.

GV: And Joe, how did you conceive this new show, Auto Didactic?

Joe Harper: Part of the significance of the Kustom Kulture exhibit was the fact that it had bridged a gap between the automotive and art worlds by bringing this car-centric culture into an art museum. Even though we are an automotive museum, we did not simply want to do a Kustom Kulture III exhibit, so we decided to focus on the link between the exhibit and the development of Juxtapoz. Because it is going to be displayed in the Petersen’s Armand Hammer Foundation art gallery, we wanted to link contemporary artists shown in Juxtapoz with a philosophy going back to Kustom Kulture and their combined origins.

GV: What inspired this particular title?

JH: In doing research for this exhibit, something that kept surfacing were stories from artists about how they were being taught in school. The title was chosen as a way to describe artists who followed a new or different school of thought, which they largely defined for themselves by negotiating what they were being taught with their own passions. The term “auto-didactic”—having the ability to educate oneself—seemed to really fit, especially when hyphenated to stress the “auto” aspect. Once we had the concept, we approached Robert, Suzanne and Craig, who all have a long history with the Petersen.

GV: Von Dutch remarked that “Modern automobiles need some human element… without it, they look like they've been ground out be a mechanical monster—which they have!” Is the car the driving force in Kustom Kulture?

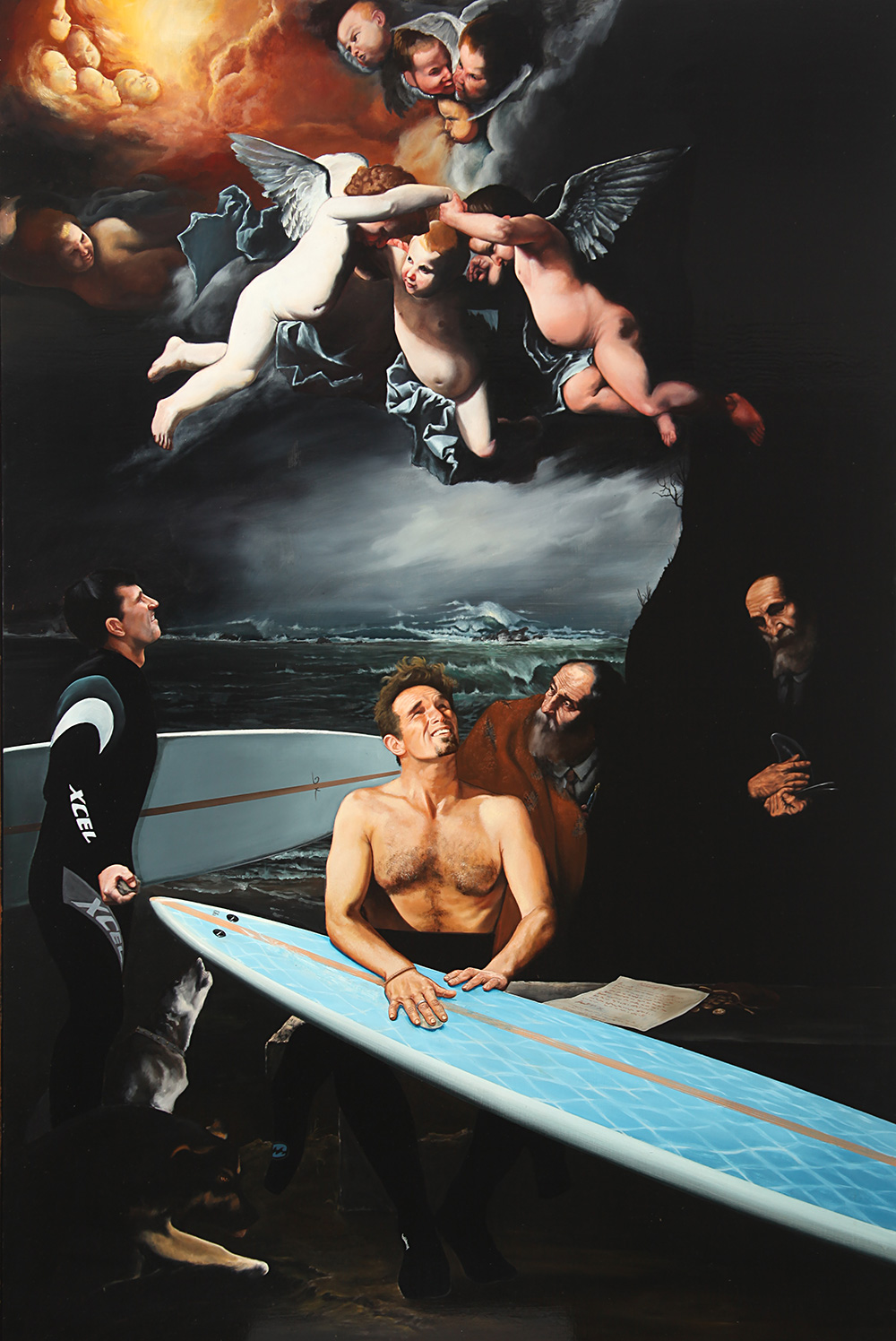

JH: The exhibit also includes underground comix, psychedelic posters and surf culture. It’s really about the relationships that exist between artists from these different genres and the automobile, and how that has changed over time. There has always been a need to connect with cars, to bring them closer to us as drivers, even as builders, and this is really part of the drive of customization. You can hear this in Von Dutch’s comment, that we should humanize them in a way to change our relationship with them. I think this reflects his philosophy as the “originator of modern pinstriping” which is a use that goes back to the Industrial Revolution when it was used to transform cold, lifeless machines to warmer, more relatable items such as sewing machines and horseless carriages (transferred to cars after becoming “horseless.”)

CS: I always thought it all was a form of art. I don’t think the mainstream necessarily did. At best, there was a tacit supposition that the automobile might be a utilitarian product with just a hint of tapped out industrial style. The Kustom Kulture shows identified and made statements, putting out the hypothesis that a lot of this could be art, or at least, culture—terms I think of as synonymous. In the fine art world, it was heresy to present such things, though a number of artists first presented in a museum context via Kustom Kulture have continued to be recognized in the world of haute art. We take no credit and we make no apologies.

GV: It’s as if the car is a piece of sculpture to which we can all relate, something we all use in one way or another.

JH: Cars are more than mere transportation, and as objects of everyday life, they deserve to be examined more closely. There is an aesthetic dimension to automobiles that link individuals to society and culture at large. Most people use cars as a form of self-identification or perhaps self-projection, and whether or not this self-image is true or false is not the point. The car is a medium of communication. As is the case with many industrial products, we rely on others, and in this case, car-designers, to communicate ideas about ourselves. What is interesting about Kustom Kulture, going back to the early hot-rods, and Lowbrow Art, in general, is that their practitioners are not simply passive consumers. They use the visual elements of an existing mainstream mass culture and appropriate them, reinterpret their meaning, or completely subvert them in order to change their function in society.

CS: The Wright Brothers were bicycle mechanics who invented mechanized flight. Henry Ford was a farm boy who eventually built 15,000,000 Model T cars, lightweight, bulletproof and economical. Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg started in tiny rooms and garages. Those four manifested modern personal computers, operating systems and social networking. Transportation and communication have become synonymous.

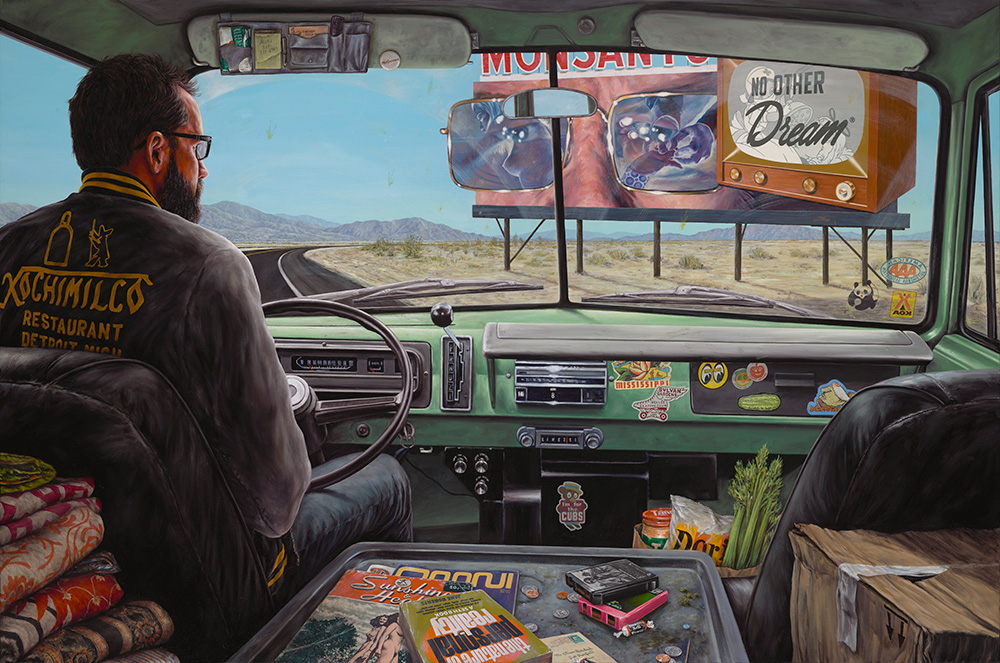

GV: Robert Irwin compared the car to being one’s home away from home. With traffic and so many places to go, we still spend as much, or more, time in them. But with keyless entry and navigational tools, has the relationship become less personal?

JH: In a well known story, Irwin had attempted to show an unnamed east coast art critic how analogous the process of building a hot rod was to artistic production. Driving the critic out to see a young man who was in the process of building his car, Irwin argued that he was making the same artistic decisions artists make in the creation of their art. However, the critic was unable to comprehend Irwin’s proposition. The two argued about it while driving back, but I believe the story ends with Irwin leaving the critic on the side of the road.

It’s not uncommon for people to own a car that they built and another car they bought for practical purpose. But building a car, particularly a custom car, probably defies all marketplace rationality. Building a car can take years of tortuous decision-making, resulting in a lot of delayed gratification. Like art, the creative impulse is a desire to reimagine reality as it is presented and go about the long process of transforming it by putting these things out into the world.

CS: For some, the automobile has evolved into a mobile atelier, a base of operations or business control and command center. People want to communicate and they need individualized expression. The best thing about living now is that media is completely controlled by the individual. Any person from any place can use a phone to make an image/film manifest, dispatched via the web for millions of people to see. It used to be that the technologically elite controlled information dissemination, but everybody now has an equal playing field. Mobility is a logical asset in the endeavor of content creation.

Consumers, in general, demand personalized transportation forms that are special. Some will modify and invent new forms. For example, the Beijing artist Brother Nut fills his surplus military van with polluted water from Xiaohaotu and presents this in random spots on the street as “The Moving Art Museum.” In the wake of Nut’s art activism, the government announced the creation of a new water supply and purification network. So mobile art produces real change.

Other people prefer to go to the dealership and order factory options, which are manifestations of their dreams and comfort level, or perhaps a desire to be seen differently. One person builds an interactive thinking fortress while another denizen selected a purple rather than blue interior for their Prius.

GV: As pink Lyft logos become as identifiable as car company ornaments and autonomous cars on the horizon, what is the car’s role in terms of sanctuary and right of passage? Does the show convey what we might be losing?

JH: The automobile has always symbolized a certain freedom, but truthfully, the nostalgia for the early days of hot rodding has become an increasingly foreign concept to the generation that came after. While it has been awhile since the car has represented the type of “home away from home” described by Irwin, we never lose the need for sanctuary, creativity or even right of passage, so they just end up shifting elsewhere or changing their from, as they should. In today’s technocratic society, sanctuary is found in anonymity, which is the antithesis of building a custom car, but I think it says more about society than in practices. This exhibit is an examination of the connective tissues between art, cars and culture.

CS: It all depends on whether you interpret the aforementioned as being Shakespearean, where the shifts are tragic and predestined, or as being Faulknerian, where the changes are grotesque and confounding. It’s not what you look at, it’s what you see.

GV: With freeways built around the automobile, southern California is naturally car centric, and the presence of Hollywood amplifies the fantasy. What makes this so appealing?

JH: It started with a concern for speed with guys stripping their cars down to make them lighter. However, “Customs” were less about the pursuit of speed and more a more radical rethinking of Detroit design. California, and Los Angeles in particular, with its moderate climate, became the center of customization as speed equipment developed at the nearby dry lake beds. Now there is an entire generation of Hot Rod traditionalists who have gone back to the early aesthetic of speed, rust and making do with what you find. There are also those who no longer care about building their car in relation to the “the right way” and they have branched out to borrow from all kids of custom cars, including hot rods lowriders, bombs and muscle cars. With all this history and mixing, there is a greater emphasis on technique and craftsmanship, aesthetic decisions that must be contextualized by “reading” the car as a complete concept. This is what makes Kustom Kulture so interesting; it cannot be reduced to simply being different from mainstream culture. While it starts with a car, it spreads into all aspects of visual culture to the point of becoming a lifestyle.

CS: The need for speed and the desire to get someplace else. Route 66 facilitated the nation’s greatest manpower mobilization during World War II. The mythical roadway ran from Chicago to Los Angeles. By 1955, there were 52.1 million cars registered in the USA, and in 2016, some 268.8 million were operational in this country.

GV: Do you think that street art parallels this movement?

JH: I think there certainly are parallels with street art, which is probably going through a similar process because of its relationship to graffiti. It is very interesting that Street Art can command prices that it does yet many artists are still being arrested based on outmoded considerations of what constitutes public art. Unlike hot rods and underground comix, it is not illegal to own or sell, but similar to tattooing, it is still illegal to practice. This suggests that street art itself is not illegal but that just being a street artist is.

CS: Prehistoric paintings, Pompeii’s graffiti, generic outdoor advertising, the sculptural stone markers on Rome’s Appian Way and the gilded bronzes sculpture at its mile zero convergence point are several common antecedents for street art. The Roman Empire had 53,000 miles of paved and concrete road, and for a modern comparison, note that the USA has only 42,000 miles of Interstate highway.

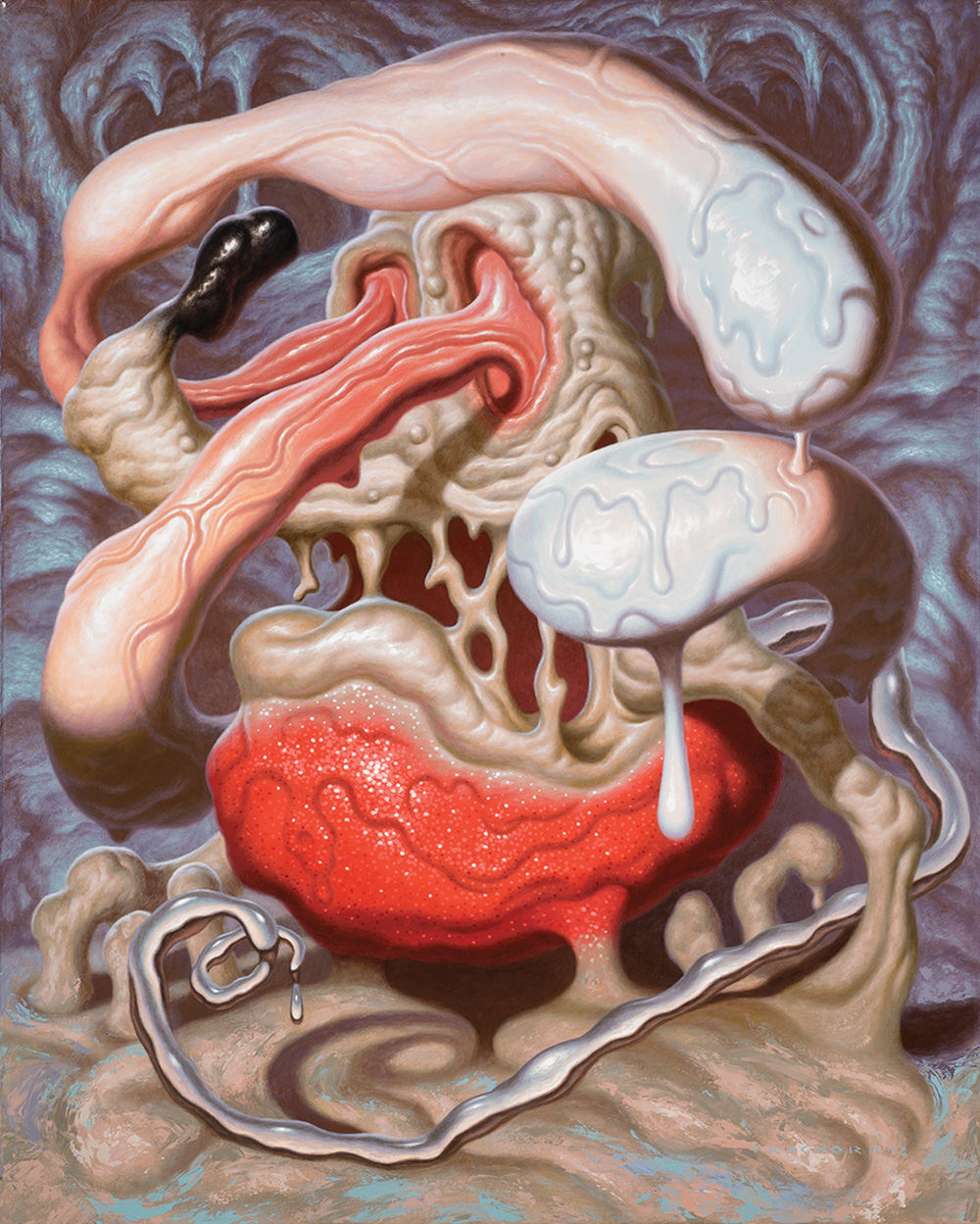

GV: Besides cars, lowbrow art (or feral art, Robert’s preferred attribution, was hugely influenced by television, comics, album covers, psychedelic posters and tattoos. What feeds this inspiration as it continues?

JH: All these varying sources represent an interest that most likely already existed but were deemed unacceptable because of social and academic proscriptions. Hot Rods were once taken as “remediation” to speed, and owning one was equated to proof of an intention to break the law. Underground comix were ruled obscene and their distributors were arrested for selling them. Oklahoma became the last state to legalize tattooing in 2006. The same is true of nearly every youth-based genre of music: rock ’n’ roll, punk, hip hop, the list goes on; they were all thought to promote sex, drug, and violence among the impressionable. Over the years, they have moved back and forth between being illegal or perceived bad taste, but eventually all became valued forms of artistic expression.

CS: Mark making is ubiquitous. People need to be entertained and they seek objects that are compelling. Michelangelo opined that, “Genius is eternal patience.” Ed Roth stated that, “Good art sells.” Those two statements are a summation of the nature of art’s creation and presentation over the ages. Trash and treasure are as interchangeable as they are situational. Altars and dumpsters are equivalent places of worship.

Auto-Didactic is on view September 29, 2018—June 2, 2019 at the Armand Hammer Foundation Gallery at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, California.