Toyin Ojih Odutola

Infinite Possibility

Interview by Kristin Farr // Portrait by Abigail The Third

Toyin Ojih Odutola was born in Nigeria, grew up in Alabama, went to art school in San Francisco, and now lives in New York. Her geographical, literary and creative influences stretch across multiple perspectives, resulting in rich portraits about the landscapes of experience. Prolific in multiple mediums and collected by countless museums, she maximizes the potential of her conceptual portraits exponentially with each new series.

Kristin Farr: Tell me about the unique treatment of skin in your portraits.

Toyin Ojih Odutola: The skin in the drawings I create was initially an investigation into what skin felt like, to live in that space and the way that affects how the skin is defined, how it is read, how it creates parameters for movement and possibility. I wanted to analyze that through the platform and vehicle of skin, to have it serve as an access point. The style I employ was my way of questioning that surface and seeing the ways I could expand on it. Since then, the investigation has evolved to tackle how the skin can be placed within a composition, how it it works within a larger system on a picture plane and, by extension, how the skin is placed in a public forum. I generally work from a formalist lens, playing with the way surfaces influence our perceptions of things, of people, of places; but I am also interested in the conceptual inclinations associated with skin, with the figure, with a subject’s surroundings—the spaces characters may or may not inhabit outside of their person. I look at the figure, as well as the scene where a figure exists, as landscapes our eyes and minds travel through. I like the term “traverse,” because it encapsulates what I am doing in the mark-making of an image, as well as how a viewer interprets a work. The application mirrors how an image can be understood. And since everyone has their own distinctive frame of reference, the reads involved with my drawings range from scarification, to hair and muscle, to the internal, intangible workings of a person, to the political implications of race and class, and so forth. I don't discount any of that. I actually welcome it; but when I initially set down a composition or sketch out an idea, I am not thinking about those things at all.

What kind of tensions or juxtapositions are you thinking about?

I like to place contradictory elements together in unassuming ways, to expose those elements in the work. This is a preoccupation of mine: whether these elements are compositional (i.e., aesthetically) and/or conceptual, it extends to include the contradictions inherent in the systems we live in, how we present ourselves to the world, and how we move through the world. There are actions that read louder than words, and to express them in forms that seem established but also absurd is really attractive to me. I often place things together that otherwise wouldn't be, but in a form that feels like it very well could be. I want to show how the combinations may very well exist.

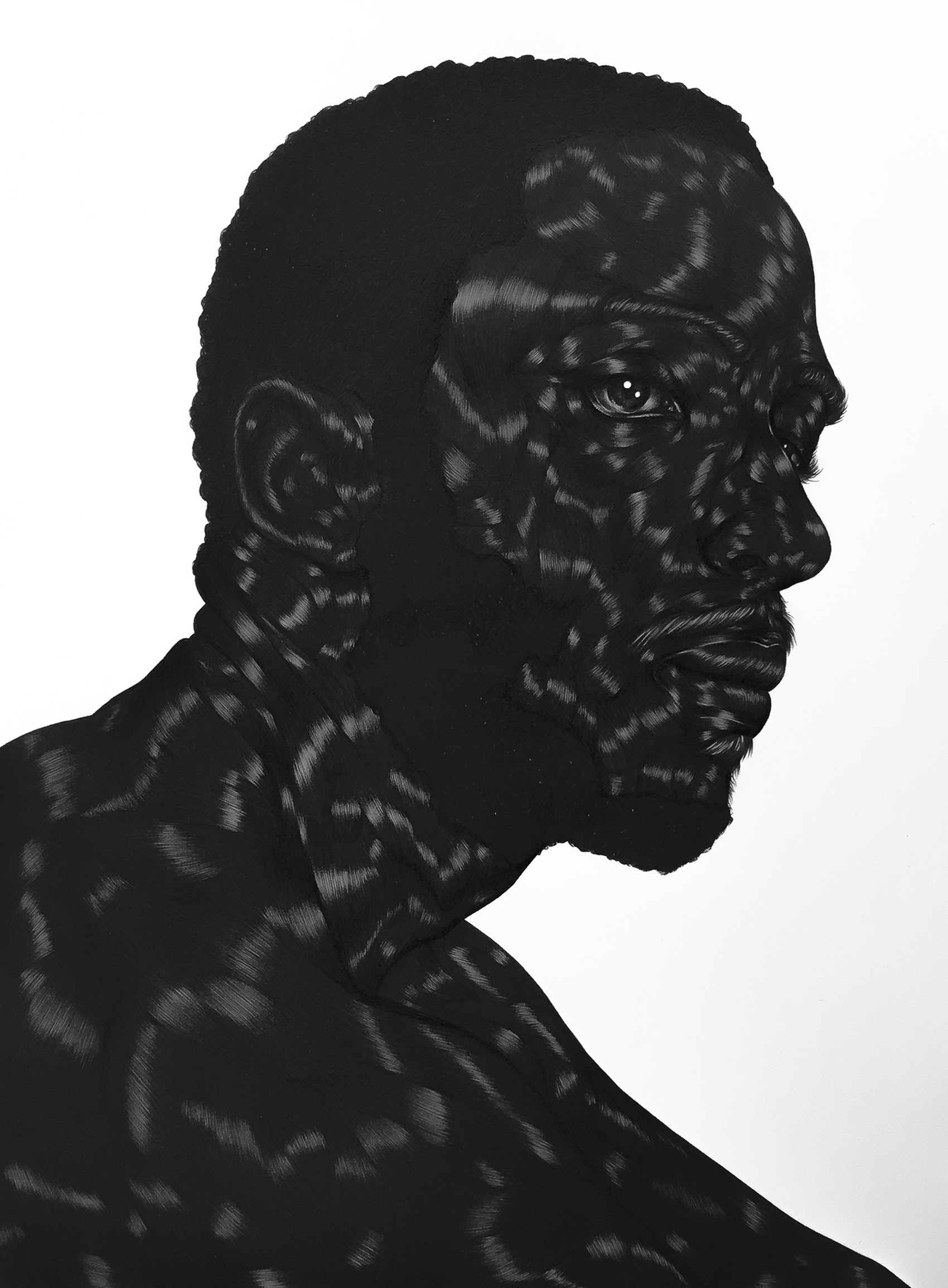

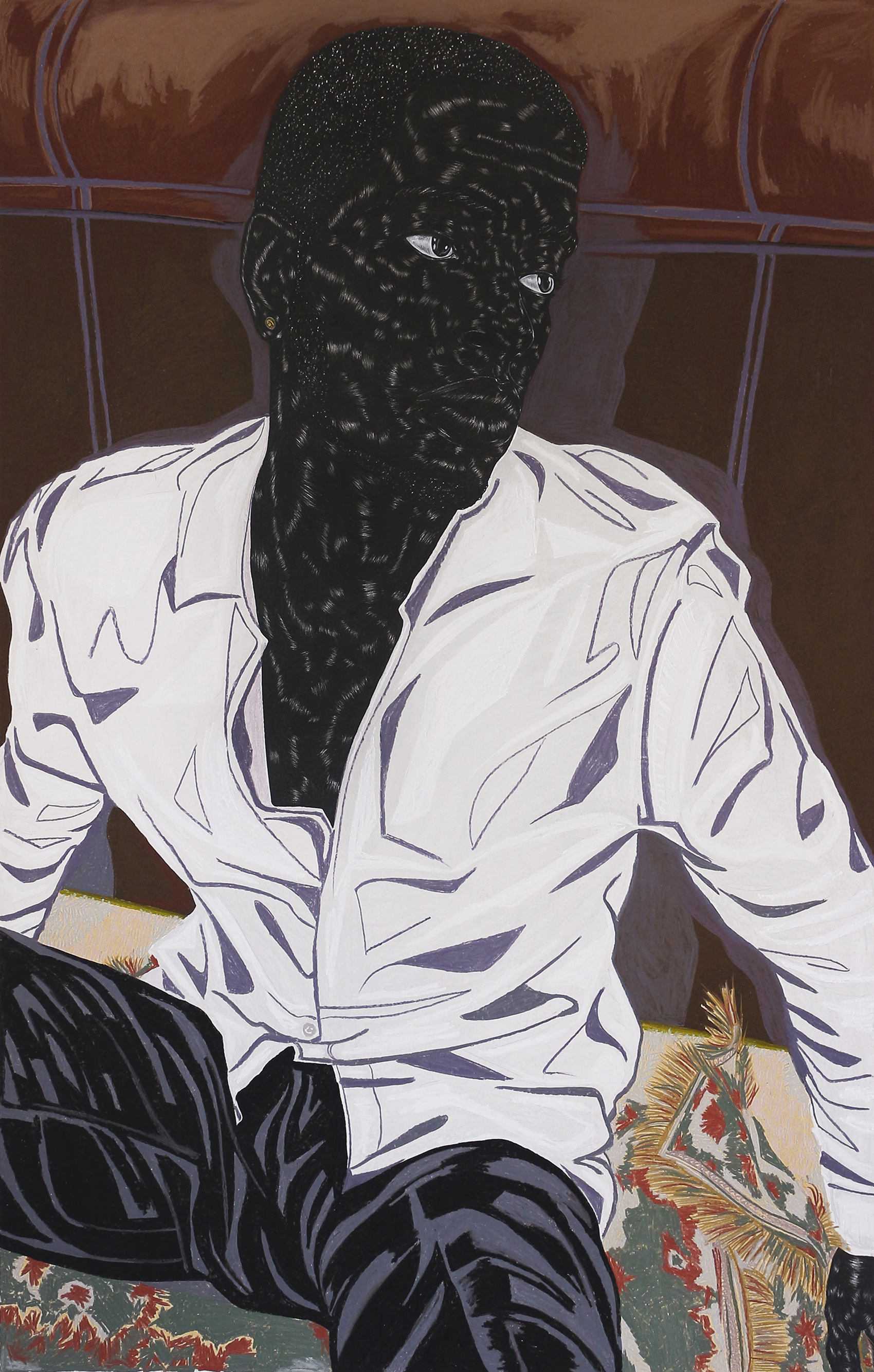

Those elements are snuck in every now and again in the most random of places within the drawings, which require a studied look in order to find. The style I employ for the skin is riddled with tensions inherent in the mark-making, and I always like to tease those tensions out slightly, playing with the planes and crevices of the skin’s form—for the skin is a bit of a puzzle I’m trying to solve. The marks aren’t placed automatically, nor repetitively; they only seem to be. When I am drawing the skin, I am mapping out a territory, which seems familiar to me but is always strange and foreign whenever I engage with it. So, I am discovering it as I am drawing out the figure. The tensions that arise and reveal themselves become so in the process of the making, and I love how every skin layer is different from character to character—even if I’m the only one who can see this.

What is the ongoing relationship with color in your work?

When I first started showing my work, around 2009, 2010 or so, I was very insecure about how to compose a polychromatic palette in an interesting way. I worked mainly within the monochrome because that was something I felt I had a handle on, and that monochrome was a tool. When you see a figure in one tone, your first reaction may be to dismiss it—especially if that figure is rendered so heavily with mark-making and is dark. You see the solid form and that silhouette may appear impenetrable or difficult to access, but the data I pack into each surface usurps that conclusion. When you step closer, the machinations reveal themselves and the figure starts to unravel.

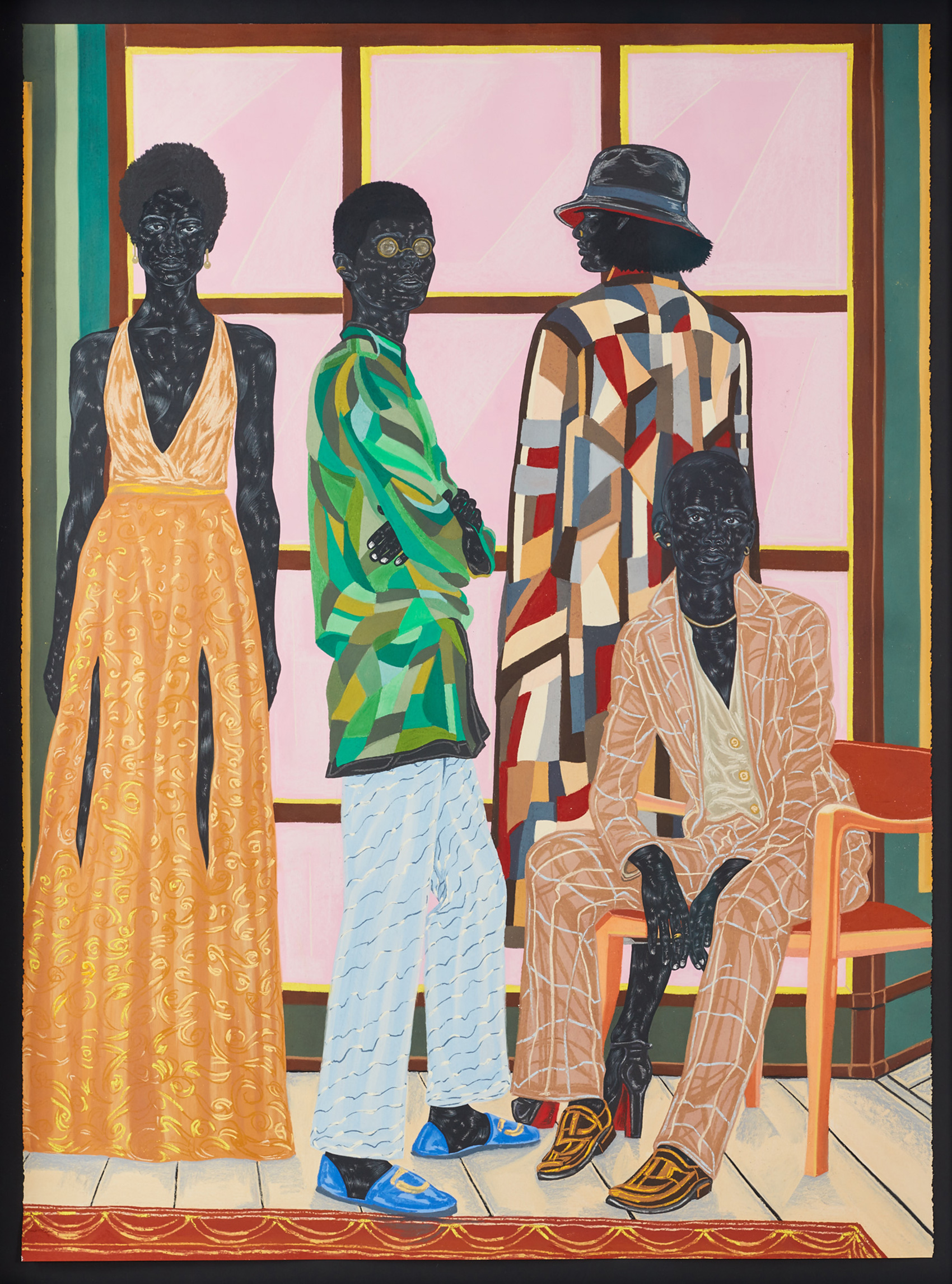

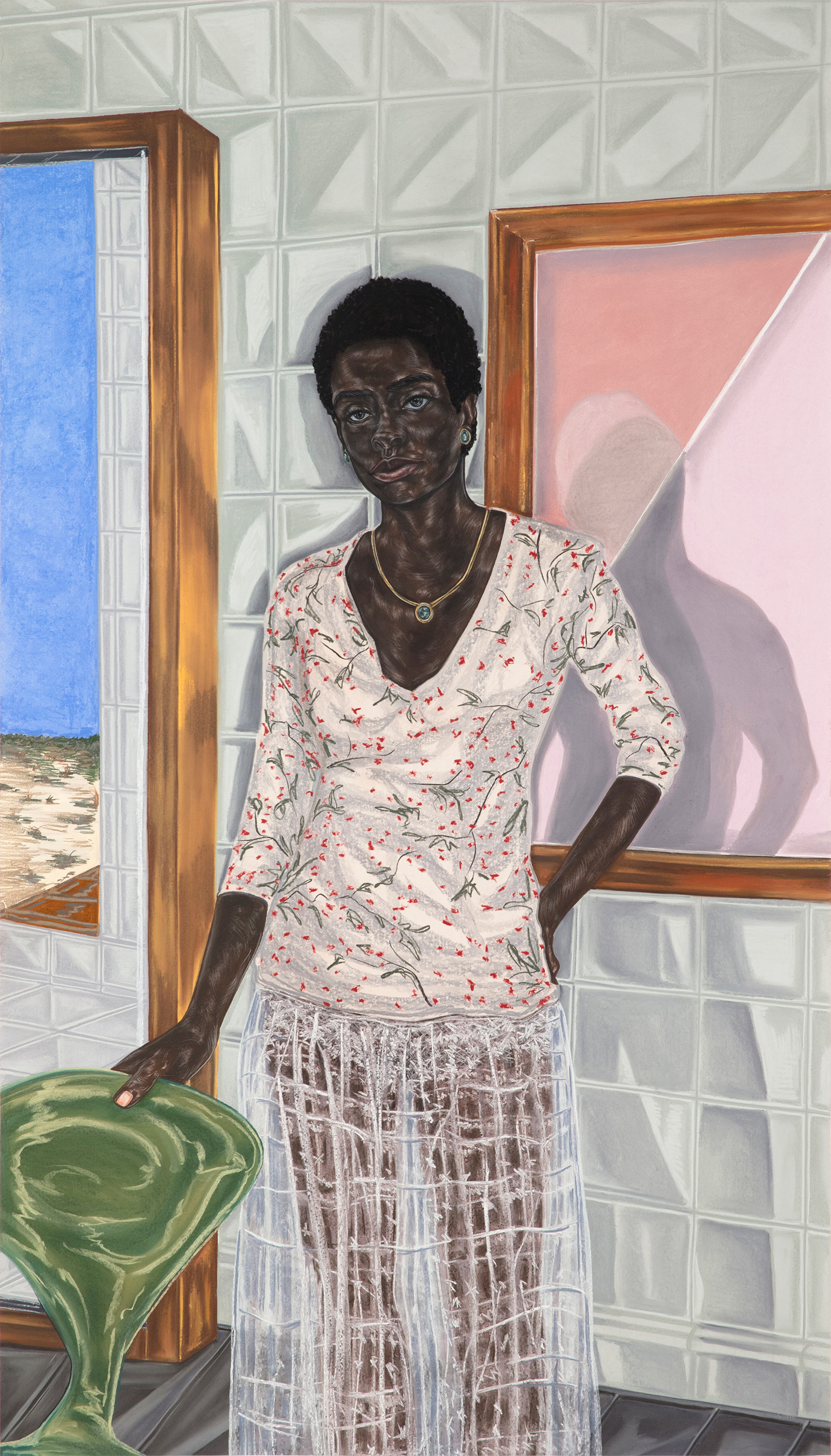

This was my aim for many years, trying to get the viewer to see the layers which compose a character, and those layers expose how we see the world, what we believe, etc. The inclusion of more colors came slowly afterwards. I tried to get at that same layering, placing more varieties of color underneath the marks I was making, then slowly moving those colors forward, taking over the space of the entire picture. In the earlier works, the subjects were often isolated, in decontextualized spaces. They only interacted with the viewer or themselves—the narrative was limited and sparse, but the presentation was striking and conspicuous. When I started taking more risks with the palette, color became a tool that I included in the language of the skin as well as the surroundings, expanding the read of the drawings, and the renderings became more subtle. Everything I place in the picture plane has to be intentional, It has to serve a purpose in how the work is read. I like the idea of reading a work as a code, the way one might read a letter or a novella. The drawings I create now read as episodic, even when they are a part of a larger series. The polychromatic palette provided more options for how to engage with that, but it took some time to get there, and I am still learning.

What do patterns symbolize in your images?

I read mark-making as a form of language, the same way one might read English. Because I came to the States at a young age and didn't speak English, I remember watching television and reading people’s actions—either overemphasized or subdued—as a means of communicating, of understanding. I thinks that’s why I have such an affinity for animation, because that is how I first came to understand the importance of nonverbal communication and expression, particularly Disney animations and Japanese anime.Productions like The Lion King and Mulan, as well as those from Studio Ghibli and films like Ghost in the Shell and Vampire Hunter D gave me life. “Reading” those animations helped me hone-in on that skill in order to process what was happening around me.

Moving to another country can be overwhelming, especially when there is little to no possibility of returning to the comforts of where you came from. It’s not enough to just assimilate, you have to constantly readjust yourself and the space you occupy in order to move through this new world you now inhabit. Images and how they were presented provided a gateway for me to do that, and now as an image-maker, I am always trying to get at those esoteric and universal signs and symbols which can cut through various reads and cultural staples. We often fall back on the spoken and read language as a unifier—a means of settling something or cutting through the disparate noise—but what about visual language? I utilize pattern in this way, as a unifier, to question those symbols or notions that seem to be a given.

The skin is an arena for this, as are the spaces where a figure can exist. In my work, nothing is a given or taken for granted, everything is questioned, even a mud-cloth pattern or a hint of a batik print serves the purpose of that questioning. I want to ask why we expect certain elements to exist visually in a certain way, and in order to do that, I have to employ elements that seem familiar with those that do not. Because what may seem strange is completely normal elsewhere—be it culturally or otherwise—the function of every element I place in a work is to draw out those questions of why things are presented the way they are. Once you see that invention is the only reason behind the things we expect to be, that’s when you understand that images can purport so much more than simply a rendering of a subject in a time and place, they can illustrate the notions we have about what an image means and how it is used—and how certain people are seen—even in the realm of the fictive.

How do you perceive the influences of all the places you have lived in your work?

The older I get, the more it becomes known to me that I have the mentality of a migrant. I traveled so much as a kid that the idea of a staid and true definition or thing, or more specifically, a steady place that I can claim, is a foreign concept to me. I grew up without a safety net. My life was defined by precariousness. So, I never understood this notion of “taking things for granted” or always having something to fall back on. It’s strange that I leaned towards art making as a means of understanding the world, because the effort of art making is a very precarious undertaking. When you gather the confidence to put something down on a surface, to create an illusion, you are playing with all the tools you have gathered—including where you grew up, how you grew up, etc. And because so much of how and where I grew up never felt like my own, never felt certain, I use art to create that for myself. It can be seen as world-building, but the act of drawing for me is a cultivating act. The land I am working with has been plowed through, eroded and mired so much already, before I come to touch it, so I am coming in from a state of possibility—because I’ve never known of anything else but the tools I have gathered before me. Each drawing I create is my way of crafting a home for myself—in fact, the very act of creating for me is a home-space, and it is very precious to me. I try to protect that.

How do you respond when the question of identity comes up?

I refer to my drawings as conceptual portraits, because their purpose isn’t to simply depict a person in a specific place or time, but to create a character in a possible space and time. The inquiry is key. I’m more concerned with presenting something that might be as opposed to something that already is. It’s a strange way of describing my thought process, but that is the closest I can get to illustrating what it is I do. Identity art is such a specific movement and work, it deals with concepts which my work can be associated with or adjacent to, but it’s not aligned with mine. When I first began showing work, I was clumped into that category based mainly on the fact that I am of Nigerian descent and my subjects weren't seen as anyone but black, and thusly, they were deemed works about blackness. In a way, I was exploring blackness, but not in the reality that is lived, though. In truth, that experience obviously affects the work as it affects my daily life as the artist creating the work. That entire series is about witnessing ideas take form, that is all. My work since then has expanded on that idea: what might come when you witness an artist grow up in a very public way; witnessing her change her mind and evolve. Is it about identity? Or is it about pushing one’s work beyond those limiting parameters to see how far blackness can go, what it can contain, how it can evolve, where it can exist, what it can claim? Identity is just the starting point, it’s not the final destination.

The black figures in that work existed in my imagination and were more of a record of that internal world made tangible. I think the work I am making now is the work my nine-year-old self was imagining, the way that earlier work was what my five-year-old self was conjuring. These aren’t documents of identity or identity politics, because what this work questions is the very notion of an identity—what it serves and how it is read. The drawings I do question identity; they reveal the lie that one chooses to believe about a person, a place, a thing. I’m not concerned with documenting my daily life as it is, but the vignettes of things, moments, memories, things that don’t make sense entirely, but aren’t necessarily surreal. There is reality in my work, but that reality is a scaffolding for the imaginary to emerge, proliferate and roam.

During an interview for one of my earlier shows, I was asked what I thought about when I was drawing the subjects, which, at the time, were modeled after myself, and whether I was trying to explore what it meant to be a black woman today. I didn't understand that read at all because it seemed so literal: vis-a-vis an image of a black woman in a space must only be a black woman in a binary space against whiteness. The “othering” of my work didn't bother me, it was how otherness was seen and what it encapsulated that was so confined. The infinite possibility of the imaginary was never included in the questioning of blackness, never even considered. When I look back at that work, the series for my solo show (MAPS) in 2011, for instance, I see it was entirely the workings of my internal universe. Whenever I look at the sequence drawings from that time, I can see the thought process behind them utterly exposed. It’s a rather vulnerable series, because it was the first time I took the inner machinations and exploited them in such a revealing way. I no longer go that far in exposing my methodology, but what came out of that work was a need to explore the internal in a more layered, complex way. I can see now how the nakedness of that work could lend itself to identity art, but those drawings were more about an artist discovering herself in the process of the making, not about explicating the state of a black artist in the world today. As if to take the backdrop of a story and push it to the fore when the content, the actual story plays out, is far more nebulous.

Tell me about your brothers who have appeared in your drawings.

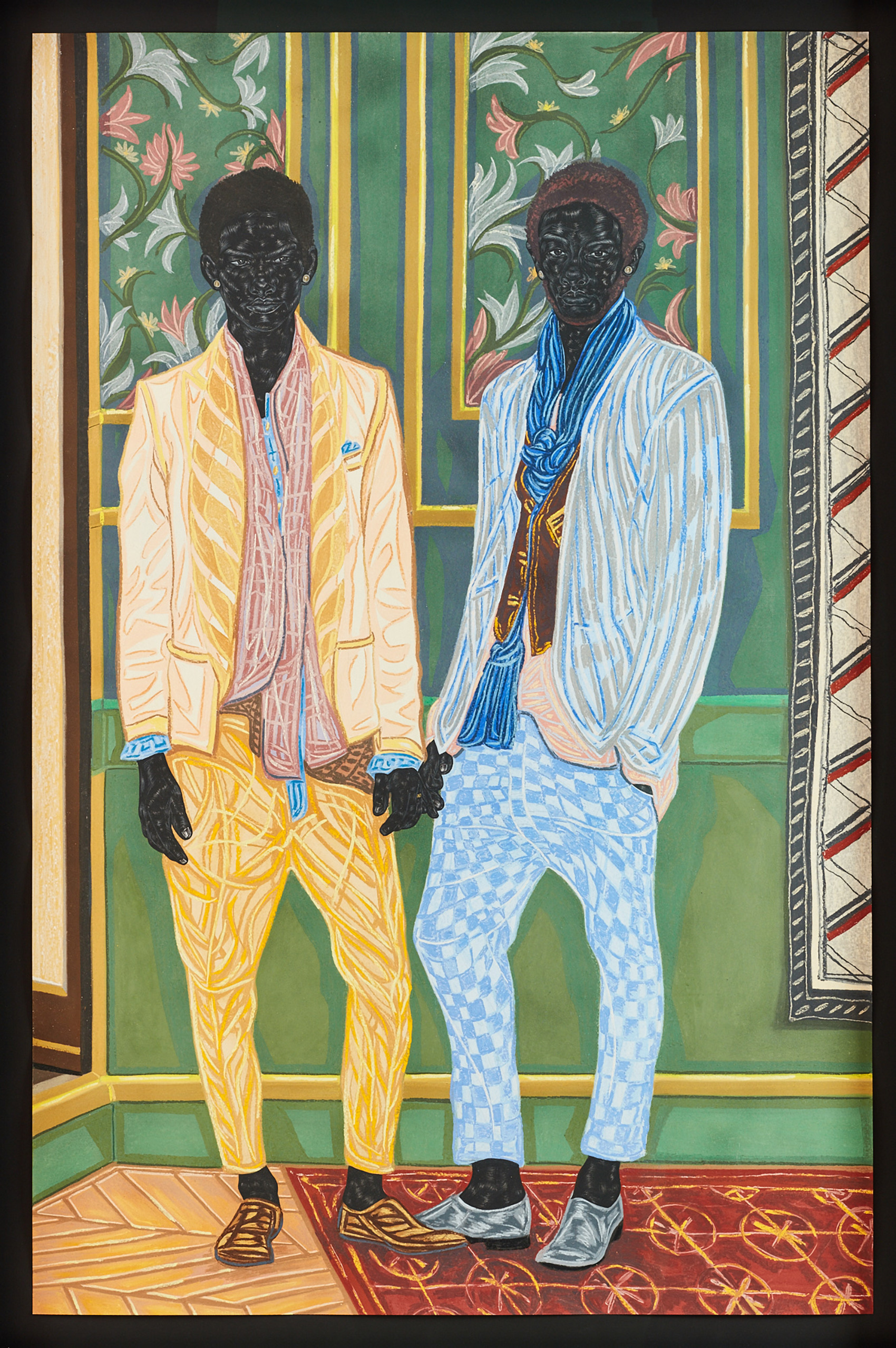

I have two younger brothers, and they are often featured as characters in my drawings. This is partly due to proximity: when I first started showing and needed subjects to draw, they were there, so I drew them—the same way I would use my image in my works. From the drawings I made where they were featured, it was often to explore an aesthetic or conceptual idea and not so much an investigation into who they are as people. That’s private. The only work which came close to that investigation was a series I did in 2013-2014, Like the Sea. The show was an expression of my appreciation for them in my life, yet it was also an exploration of the value they hold in their existence as black men in our country. The series was the very embodiment of that phrase, “the personal is the political.” I wanted to create a body of work which could reach out to them and so many others like them, to let them know that they are enough and they are beautiful. It was a very literal series and it was important for me, personally, to do that work at that time. It was a capsule.

What are some challenges you’ve imposed on yourself?

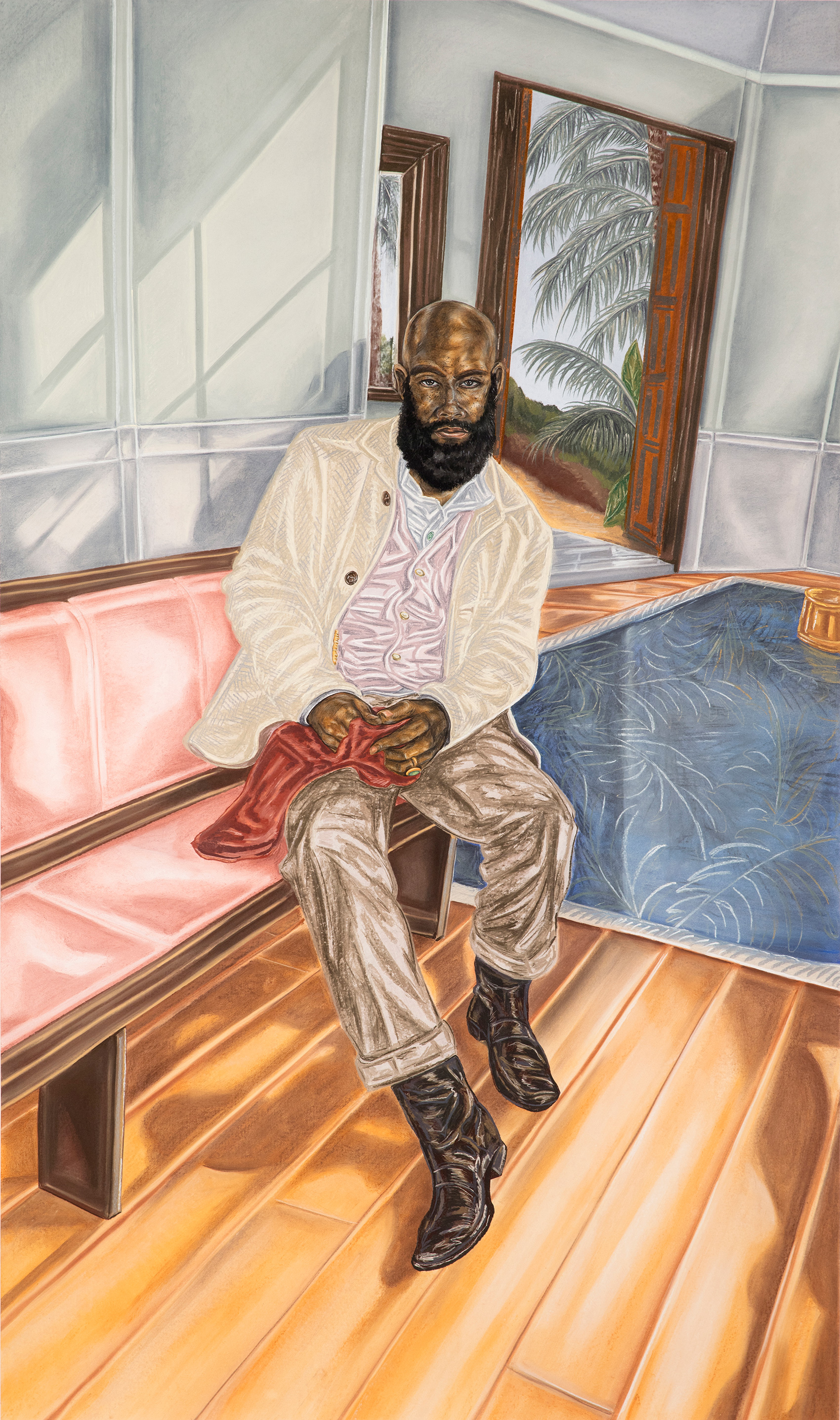

I’m always placing restrictions on myself whenever I start a series. It can be how each drawing is composed, or which colors I’m limited to working with in terms of palette, or what kinds of characters I choose to render and how. I recently completed a series titled, The Treatment, where the restrictions imposed were stark: the entire series was composed of men, it was monochromatic, and the skin was the only element which was touched—with the clothes, hair and other accoutrements of each portrait purposefully left in pencil sketch. The process of making that work was incredibly taxing, simply because the restrictions were so tightly wound, there wasn’t room for flair. However, the result of that work was a very consistent, visual aesthetic that was so closely knit that it felt like a collective body, instead of a grouping of individual works. Even though that work has since been broken up and shown in different groupings, it still exists as a singular entity—and I’d never had that happen to my works before. It was a very enlightening experience creating that series.

What are you working on now?

The second chapter that follows the series in my show A Matter of Fact (2015), which chronicles two wealthy Nigerian families. Parts of this second chapter will be shown in my solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in October—my first solo museum exhibition in New York.

What’s something important to you that seems less important to other artists?

I don’t know if this is less important to other people, and I don't presume it to be, but I’m attracted to the understated in art: moments that can be quickly passed over, but are complex and layered. There’s nothing wrong with bombast, and the maximalist in aesthetic and presentation, and I often exploit those very qualities. But nothing beats the underwhelming, the quiet, the subtle. When you see the economy of line used so effortlessly—that always gets me, because it isn’t easy. You have to build up to that kind of confidence; it takes awhile to trust yourself to go there and know that what you are doing hits just the right note. When you get to that place where you don't need a lot to fill in a space and what you lay down is just enough and not overwhelming—that’s my goal… and I know it’s going to take awhile to get there. Whenever I am stuck on a particular element of a current drawing, I remind myself, “Toyin, don’t describe, interpret.” That’s the aim. If I describe, am I aiming to capture something like a camera would? Or do I interpret, where the perspective of my vision dictates how the work unfolds? It’s a balancing act, but it’s part and parcel with building up an image to its full potential.

Toyin Ojin Odutola’s solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York opens October 20, 2017.

toyinojihodutola.com