Vision Walk: NYC

With cheryl dunn

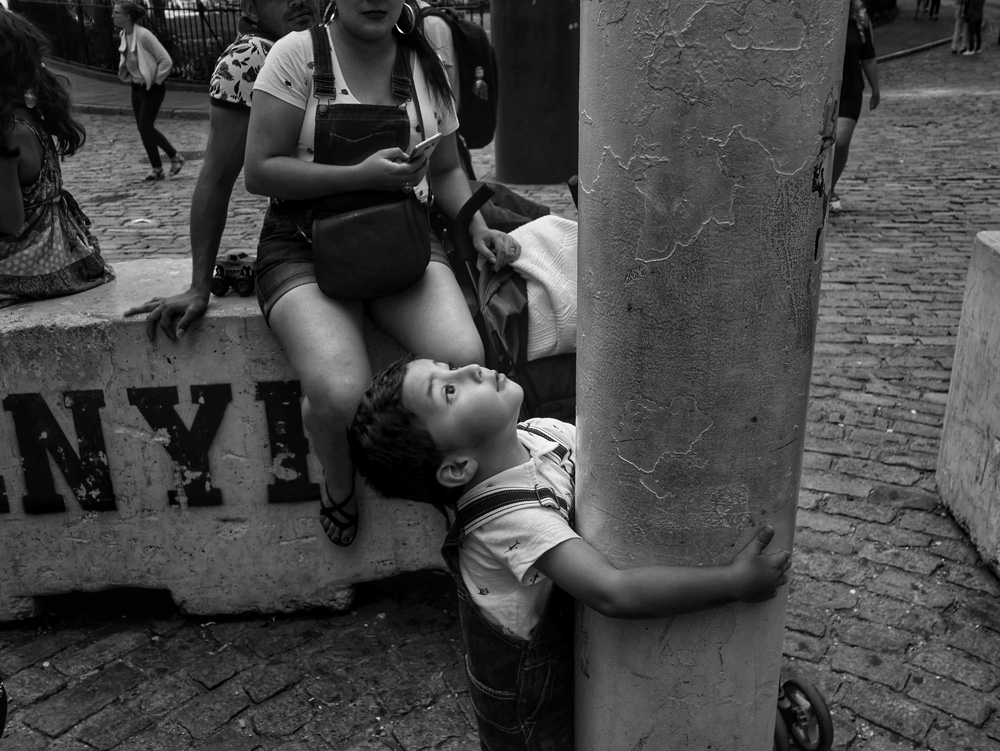

We are traveling around the country with VANS VISION WALKS, a series of workshops led by some of our favorite photographers in their home cities. This month we spent the afternoon with CHERYL DUNN as she led participants on a walk through lower Manhattan.

Cheryl Dunn told us that making Everybody Street, her 2013 street photography documentary, felt like going to graduate school. She was able to sit and ask many of the great masters of photography anything she wanted for a couple of hours. That is often how we feel interviewing artists and photographers for the magazine; it is a rare chance to absorb as much information and wisdom as we can. Spending the day with Dunn felt extra special though, because after our conversation she led a Juxtapoz-curated Vans Vision Walk through Lower Manhattan, imparting wisdom, stories, and advice she has learned shooting fashion, boxing, the streets, music, friends, art, and from making an entire film about her own photographic heroes and icons of street photography. "You just have to believe," she reminded us. "And you have to keep putting things in the world. Making zines. Making things. I think that people respond to passion, to people that are psyched and passionate about what they do."

Alex Nicholson: What were the first photographs you remember having a big impact on you?

Cheryl Dunn: I think the work of Bruce Davidson. I grew up in the vicinity of New York City and I remember babysitting for a family and they brought me to their apartment in the city. When you're in the vicinity of a big city, and New York at the time, you only get the bad news. It's just horrifying because you think you're gonna get shot and murdered. So I was this teenager in this New York City apartment, thinking, "Oh my God." Bruce’s body of work just reminds me of that time.

You first met him while making Everybody Street?

Yeah, I was very, very nervous, it was a big deal to me. He was such a sweetheart, I dropped my phone in his toilet before I even started! I went to the bathroom and this door was cracked and I peeked in and it was this magical dark room like Narnia, the back of the cabinet. I was like, "Oh my God!" and I turned around and my phone flew out of my pocket and into the toilet. So now, my whole calm demeanor was super fucked…

Do you have any favorite pieces of advice you got from photographers you interviewed for Everybody Street?

Jill Friedman, who I love and became my friend, she's such a ball-buster and hilarious and raw and crazy. Her real substantial body of work was street cops, and she did firemen. She’d be shooting very gut-wrenching things, often murders. Sometimes it would be difficult and she would just tell herself, "I better take the picture, okay, take the goddamn picture. It's your job. Take the picture." Even though it wasn't an assignment, this was her initiative. Sometimes you can bail out on that because it's just like, "Well, I made this up. I can bail." But she would say, "Take the God damn picture. That's why you're here."

"Every situation is really different just as people are different. I try to not break the thing that struck me, why I wanted to take the picture because when you engage in something, in someone, everything changes."

So, I think about that. I ride my bicycle a lot instead of walk, it's how I get around the city. You see more things from your bike, but they're going by you, right? I'll see something and it's so easy to be lazy. But then I have that thing that Jill said, "Take the goddamn picture." Not every time, but I'll go back and I'll take the goddamn picture. Because this is what I do, take the picture. Every day, I'm completely riddled with anxiety because I just want to be on the street. I mean, I'm not a drug addict, but I would imagine it's sort of like I just get wound up and I just need an hour, I just need to shoot on the street. Even if I don't get something great, if I did it then I feel calm and I could go do my tedious sit-in-one-place stuff.

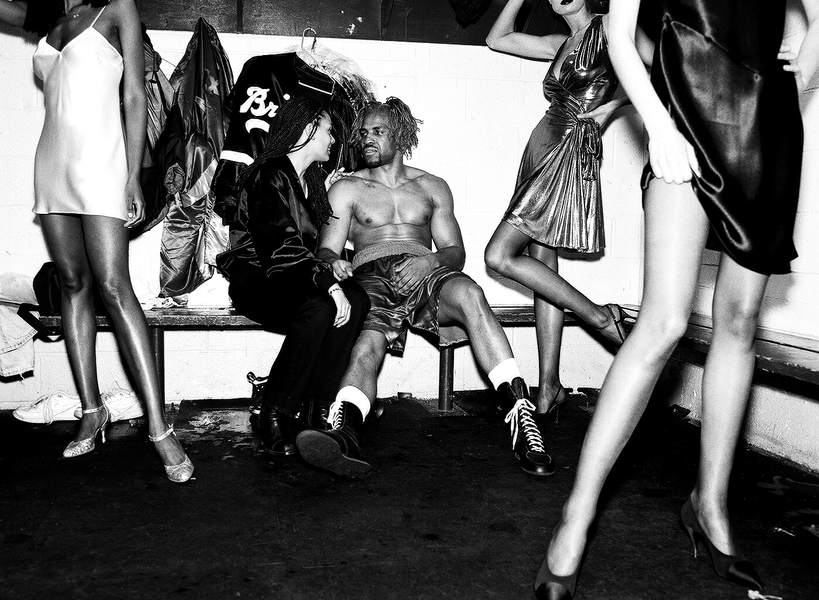

When you were photographing boxing, did it involve a lot of communication and getting to know the boxers you were shooting?

No, it was very fly on the wall. I mean, there was a crew of fighters associated with a gym that I would go shoot in Newark, NJ and they were my friends. Being a woman in that scene really served me well because I was literally invisible to these dudes. Why did Mike Tyson make 30 million dollars a fight? The whole world watched those fights. The richest people, the biggest celebrities were at these fights, some of the people that I knew in boxing at that time, the investors, these people basically controlled everything, they were ruthless businessmen that basically owned these fighters. It was like, "If you can't be the most powerful, strongest man in the world, you can own him."

One of the fighters said to me once, "People don't even know what you are." I was just some tomboy chick with a camera, there were no women in that world. I would be in a room with guys saying things I don't think they would ever say in front of chick. I was trying to be a commercial photographer, make a living, and survive in New York City. I had access to a pretty inaccessible world at the time, and I just went in there and thought, "I'm just gonna use this as a study and to practice. I don't have a deadline, it's not an assignment. I can fuck up, I can learn the psychology of people and how to work really fast." If you're ringside you have to pick a place, you have to fight. I was always the only chick. You have to fight for your place on the ring with all these dudes. You have to hope that the knockout happens in front of you because the odds of that are very slim. I was shooting film so you had to make sure you were not at the end of the role, that you had the right lens on, so of course, you miss many shots.

That's why when you see a really perfect boxing picture it's phenomenal because it's really hard. And you go back to the guys who were shooting boxing in the ’30s and ’40s with the fucking one flash and they get the shot. And it takes three more minutes for them to set the 4X5 camera back up and the magnesium flash bulb, I mean that's insane. So, shooting the fights was really great practice. In hindsight, doing a lot of interviews after I made Everybody Street, I realized how influential those skills were to street photography as well. You have to be ready in one second.

Your mind wanders and you miss the moment.

Yeah, you can't take your eye off the action.

So do you mix it up when you're on the street, being a fly on the wall and approaching people if they seem interesting?

Every situation is really different just as people are different. I try to not break the thing that struck me, why I wanted to take the picture because when you engage in something, in someone, everything changes. That's not always easy, nothing is ever easy actually. Also, I try not to be exploitive and hurt people's feelings.

Do you feel anxious if you have your camera and you're not looking for a picture or shooting something that is happening? Do you ever think, “I should just experience this."

Shooting doesn't hinder my experience. I usually shoot a few then stop and be in the moment. Then maybe I'll take some more in a little while. If I didn't shoot something I would be having a less awesome experience. I like to say I'm a participatory shooter. If I'm shooting people dancing I am doing it while dancing.

The only time I ever never shot pictures was at Burning Man once. Because it wasn't really my scene as I just happened to go with a friend who was a photographer. That was the only time really I would say in my life perhaps that I didn’t shoot pictures of something.

The skills you learned in boxing must have helped a lot with shooting music.

They all did really. There are lots of skills that are very similar and different but ultimately they all are about reading people and studying how people move and working fast and not missing that moment. They all have that in common.

We talked earlier about the 16mm footage on Everybody Street. It feels like what walking down the street as a photographer is like.

Well, that was my medicine for my anxiety about not being able to shoot too many stills during the duration of that. The 16 was my street photography that I could incorporate into the film. I really wanted, as much as possible, the complete, total, visceral feeling of being in the street. How sound feels. If you walk, how does sound come in and out? If you're on a bicycle, you're this much higher, and the sound is going by you at this speed. If you're skateboarding, how does the scene look like? I wanted to build all these ways that you experience sight and sound and image in New York City. The film was about all these sorts of people's viewpoints. Getting low, getting high, you know. That was what my motivation, and also it was my way of flexing my shooting when I was making the film. Then you get to weave them together and kind of set a mood.

Was there anything that you learned from making films that translated back into your still photography?

For my 16mm, I have this weirdo 6 mm TV lens, it's wide as hell. I learned how close I can get to someone, and them not even notice me. I've taught a few workshops and I tell the kids, most people are afraid to get close to strangers or they won't get in their face, because it's ethical, it's whatever, it's weird. I tell them, "Step closer, see how many steps closer you get before someone even notices you're standing there. You'll be surprised.”

Especially in New York.

When you are in crowds, you can get away with a lot of shit. And if you're in crowds with people that are taking pictures, like in a tourist place, no one even sees you.

How do people react to the different cameras you are using?

I think people are interested in cool cameras that are different from what everybody's using. I shoot Leica, and it looks old-timey. So many people come up to me and say, "Oh, my grandfather had that camera." They engage you, and they're more okay with you if you're sticking a camera in their face, if that camera looks cool, or is old, or something.

After we did the interview with Bruce Davidson, my idea was to get him in the subway, and I'm like, "Can we go to the street? I like you walking down the subway steps." He's like, "Okay." This camera's a pain in the ass to load. So he saw me loading this thing, and a lot of these guys made films and made them on 16mm, and they know what it is. I think he really appreciated that I was shooting this format, and he was way more generous with his time because he saw me using this camera. He's done it, he knows the pain in the ass, and he's like, "Oh don't worry, we can go more," because I had that camera. If I was shooting my phone or if I was shooting something else, I don’t think he wouldn't have said that.

You've been shooting music festivals for a long time. How have you noticed people's reactions to having their photo taken change with smartphones and social media?

I have gone to Bonnaroo for about 14 straight years and that was really helpful in studying exactly that because I am four days in a sea of 100,000 people, and their behavior in front and behind cameras change exponentially every year based on what was happening with technology and cameras.

I remember this weird year, some shaming thing happened on Facebook, and people would ask, "What is this for?" and say, "No, don't take my picture." Then the next year, Instagram happened or camera phones happened, and everyone was doing it more, and people were more open. After Instagram hit barely anyone says, "Don't take my picture," because they're all taking pictures all the time, and they want these pictures of themselves. They want more followers, so they say, "Send me those pictures." It really, really changes.

There was a landmark case that went to the Supreme Court in New York State that ruled if you're outside, you have no right to privacy. And particularly in a place like NY, look up at the street poles, there's like seven cameras on every one. There's like a billion cameras ... everywhere now. So if anyone says to me, "Don't take my picture," I reply, "Your picture is getting taken by 20 cameras right now. You're in public; that's just the way it is." I don't wanna be a dick, but if someone's aggressive to me, that's what I say.

You've done so many different things; films, documentaries, street, fashion, music... do you like being in situations where you have to learn a new skill on the spot or do you prefer focusing on one thing for a while and getting really good at it?

I like learning new skills. I'm obviously not focusing on one thing. I wish sometimes that I was like that. I always think about how some painters are every day in that studio, and doing the same thing, or subtle variations of the same thing. I need to have adventures. I need to be in the world. I think my work is a bit schizophrenic, and maybe from the outside, it looks, hopefully, less schizophrenic, but I guess it's my personality.

Yes, I like new things but I don't necessarily love to know everything about Lightroom or know everything about Premiere, but I have to be self-sufficient. And in this day and age, if you're like, "How do I do this?" You type it in your computer and there's the answer. If you're not frustrated and you can sit there for a second, you can learn how to do anything, you know? And I do it when I need it, and then sometimes I throw that new information out of my brain because I want to save my brain space to be open for creative thoughts and ideas rather than holding on to all this technical information when I'm not using it. I can always go back and get that info again when I need it. I'm glad I can do all this stuff, and anyone can teach themselves how to do anything in this day and age. And if you can't ... you can, you just don't want to. It's a very interesting time to know how to use technology, and the answers are right at your fingertips if you want them.

Do you think about your photos in terms of how they will look in the future?

I just did a talk at ICP and someone totally asked that question. How do you know when the weird, shitty photograph, the shot you took of graffiti fifteen years ago even will matter? You kinda don't. Clayton Patterson said this in my film. He was like, "I like to take pictures of mundane things, because in fifteen years that will probably be an important document of something." And so I try to take the pictures that thrill me now. I also bang out a couple pictures of just stuff. I always used to and still do, but less so, go to most of my good friend’s art shows and I just make sure I take a picture of them in front of their work and then I bang about five pictures off of the scene. And they're whatever pictures but they're a document. Then in 15 years, someone's making a book about that show or scene. It's happened so many times. It takes about 15 to 20 years before people start making films about the past. I mean, history also changes at the speed of light, too. How many years does it take to be called history?

I've licensed this 9-11 footage a lot. And how long ago was that now? I got very dramatic stuff when those buildings were coming down but then I have lots of mundane stuff. I just walked the streets. I kinda was homeless and I just documented what the hell was going on outside just because I could. I had access to it and that's valuable footage now. At the time I didn't think in those terms. There's an importance to it and I always think that particularly with that or anything that I am lucky enough or unlucky enough to have prime access to, that it's kind of an obligation as a historian. Am I a New York historian? Maybe I am. I think about the footage I have of Margaret Kilgallen and I'm like, "Oh, my God. It's a treasure to me." We were friends and I documented her in a few instances. Who the fuck would think that you would lose your friend at 32? That's what you don't know.

You might think, "Oh, this is just a typical day." But life is really fragile and your best friend might not be there tomorrow. Friends, people, things change. It's really nice to just document stuff. It's easy. And then care for it. Care for that. Because that's the thing with Instagram and phones and stuff. People love to shoot, but do they archive, do they back that stuff up, do they label it? Can they find it? Do they care for those images? I think that's a difference between maybe someone that does this for a living or really thinks in those ways and someone who is a great Instagrammer. It's caring for the images after the fact, and that's pretty important.

Was there any point along the way where you felt like you should be doing something else? What made you realize, "Alright. This is the only thing I want to or can be doing."

I really remember when I decided that I would pursue this. I had no frame of reference for what you could do as a career and I didn't come from anybody in a family that had any job like this or whatever. I initially started working in an office and I was like, "Hell, no. I'm not doing this." And then I worked on a photo shoot with someone and thought, "Well, maybe I could do a part of this." My friend said, "Well, maybe you could be a stylist." I'm thinking, "What's that?" I had always shot pictures from high school, but I didn't know how to make that a job. Then I just went to Europe. I had a boyfriend at the time who got scouted on the streets in New York to be a model in Milan, so I'm like, "Fuck, I'm going." I got a bunch of jobs and I saved up some money. So I just busted out of New York and I went to Europe and lived really cheaply and just started shooting, really naively, thinking, "Oh, I'm gonna be a fashion photographer." Being young and naive is really important and you should never listen to older people going like, "You can't do that" or "Be afraid." Which, particularly for a woman, they're like, "You can't go to Europe by yourself.” I'm like, "What?" Like be afraid, be afraid. A lot of people like to throw fear onto chicks. Maybe they don't do that anymore. But I thought, I'll be afraid when I have my own bummer experience, but until then I'm gonna be careful, but I'm not gonna buy into your fears.

When I started to shoot, I was just like, "Everything about this engages me. I'm not bored. My mind is not wandering. I'm interested in all of this, so I guess this is what I'm doing." But, yeah, it was a struggle. You know New York City is not cheap. When I came back I had to pay the rent and to shoot and buy equipment. I didn't really have any fallback plan. I was like, "If I don't keep working, I'm gonna be the chick living in a box in the street." It was a gamble. It was a big gamble. But being freelance is a gamble, right? You just have to believe the possibilities. You have to put that energy in the world or else you're shot. You're freelance, you don't have a job. I haven't had a job since, for 30 years. You just have to believe. And you have to keep putting things in the world. Making zines. Making things. I think that people respond to passion, to people that are psyched and passionate about what they do.

Do you think that struggle can be helpful for creative growth, for the work itself?

Yes and no, but it was fire for me, but things take time. It’s not for everyone. And you have to set your priorities. Do you want to go out to a fancy dinner or you want to use that money and go to the darkroom? It's your choice. And I knew that when I was 40, I didn't wanna be like, "I wish I did that. I wish I did that." I wanted to be in a job that engaged me for my entire life. When I was making Everybody Street, I read The New York Times every day and was really clocking when there would be an obituary of a photographer. Every person was in their late 90s, shooting to the end and living until their 90s because they loved what they did. I don't wanna retire when I'm 40 because I did a job that made me a lot of money that I didn't really like. I don't care. I'd rather struggle now and even struggle whenever, but if I'm doing what I love, it's not a struggle. I'm lucky that I found something that I love. That's not always the case. Half the people in the world, or more, I don't think do what they love every day. So if you do, money is... as long as you've got enough to float it...

Fear is a really negative thing. Yeah, it's a bummer not to have money, but I'm not afraid of it. I have the foundation. Okay, this is another thing. A foundation. A body of work that's a foundation. When I was hustling, trying to get fashion jobs, I would get thrown a bone here and there, but it was harder for... I keep harping about the chick thing. But it is a thing. I asked Mary Ellen Mark this, and she said, "Yeah, people wouldn't give me assignments because they didn't think I could carry the equipment or it was too dangerous for me." So she did a lot of personal work. "I can walk up to a door,” she said, “a stranger's door, and knock on the door and they'll let me in that door. They won't let a man in there, necessarily." You just have to think about the assets you have and use them.

When I was trying to get all these jobs, I thought I was failing. I wasn't shooting Vogue and all that, but that's why I did these documentary projects. I wanted to get better at what I did. If I was shooting fashion pictures in the '90s, I would just have a pile of outdated fashion pictures. But instead, I have a documentary body of work that gets better with age. That's what documentary is. That becomes the foundation of where you stand, career, creative wise. No one can take that away from you. So even if I fell to the dirt, I'm not gonna fall to the dirt. I'm gonna fall to like a couple rungs up because I have something. That will always be there. So my failure, my perceived failure, in not getting those jobs was actually not a failure. Personal work is something that comes from your heart, from the ground up.

Do you have any other examples of perceived failures that led to something positive?

Just being loose and not being so stressed out. When I started to make films, I was 30. I was older than when I started to do photography, so I was like, "I have no time to fucking be embarrassed about asking questions." I think also as a chick, too, you had to know everything. All eyes were on you because they just didn't think you could do shit, so you had to really know your shit. I think there should be some looseness. Do what you're passionate about. Many photographers that I interviewed said things like, "Make things about your life. What do you have access to that maybe is inaccessible to other people? Go there and go deep and that should be one of your projects. And see where you get with that."

Speaking of that critique, did you have lots of peers when you were young that you could give you feedback?

No. I think it might've been more like you would go with your portfolio into an editor's office. But that's also a weird agenda. That's their agenda. And it’s political and so, no. But I used books and I did my own education. Books and museums and, yeah, just studied myself. And doing Everybody Street felt like going to graduate school. I was able to ask these great master photographers anything I wanted and be in their studios for a couple of hours. This was just pretty great.