Danica Lundy

The Art of Extended Release

Interview by Sasha Bogojev // Portrait by the Artist

I can recall the first time I saw Danica Lundy’s work in person, marveling at how the layering, perspective and dimension of her visuals seemed to open before my eyes, how a gravelly surface or metallic shine took shape from her brush strokes, how color gradients transformed the flat canvas into three-dimensional space. I also remembered meeting her a few days later at her Brooklyn studio and being charmed by her genuine, generous character, equally matched by a zestful energy that fully complemented such captivating work.

So, in order to avoid the awkward lag of video calls and exert some rebellion to 2020 protocols, we opted for a good ol' penpal method of communication. Over the course of a few weeks, we wrote to each other, covering everything from cars, to art and sports analogies, to the experience of being a Canadian living in the USA.

Sasha Bogojev: How’s life been in the last 6 months since I last (and first), saw you?

Danica Lundy: Have you ever seen the movie Dark City? It might be kind of obvious from the title, but in that city, the sun never rises or sets, and for the most part, the characters are totally oblivious to it. Looking back, I have this weird feeling the last six months could’ve just been one long night.

Kiss the Clock, Oil on canvas, 48.5” x 71.5”, 2020

As a Canadian in the US, how does your life journey look or feel like at this point in time?

Funny you’d ask this next—in that same movie, the protagonist has this vague but enduring memory of his coastal home called Shell Beach. Everyone in the city is aware of the place, but no one remembers how to get there, and each attempt to get there is thwarted somehow. And when they finally do find it, it’s just a massive poster at the edge of the city. I’m pretty sure my home in Canada does exist, and I miss it terribly. But that’s the kind of feeling I get while thinking about finding my way back right now.

It’s a strange time to be an “alien” here—maybe even stranger to be an alien in disguise. I’m assumed to be American until a certain word or two escapes, and then the game’s up. It’s even more disconcerting when I’m assumed American at a time when actual citizens are told to “go back to where they came from” by their own president. I guess any sense of stability forged here is tenuous within this kind of political backdrop.

I feel focussed here. I have a studio in a neighborhood within walking distance of a bunch of peers, a damn good man-friend—and a new dog we just adopted. I guess I feel a sense of purpose in making things, and deadlines have allowed me to side-step the over-thinking. Despite what I just said about tenuousness, there’s a totally convincing, non-illusionary feeling of home here.

Does it feel, though, a bit like having a joker card, knowing you actually do have another home and this isn’t your original home, that this president isn’t your president?

The only answer to this question is Orwellian: “Two plus two makes five. Oceania is at war with Eastasia. Oceania has always been at war with Eastasia.” Sort of kidding, although I find myself watching what I say here closely. I’ve never felt more suited to a place before. New York specifically, I mean. I don’t want to leave. And it would be tempting to denounce the absolutely egregious MAGA shit-storm as, “not my monkey, not my circus.” But that would be impossible—especially because I’m living and breathing here in the middle of one of the biggest civil rights movements in US history, where systems of oppression are being challenged and deep-rooted racial and social inequities exposed. It would be unconscionable to be on the sidelines for that.

But my American boyfriend Tim and I do talk about moving back to my island. He wants to get a float plane. We biked around on the fourth of July, fireworks popping up on the street in front of us… and Tim started singing “O’ Canada” at the top of his lungs. A little middle finger at American patriotism, I guess. In retrospect, it was funny, but at the time, I just shook my head in embarrassment and tried to pedal away. I was like, “That’s such an ironically American thing to do.”

Rust Bucket, Oil on canvas, 62” x 70”, 2019

Did the current situation affect your practice or maybe even the focus of your work?

I mean, how could you not be altered in some huge way? There are such profound shifts happening all around.

Ha, yes, it would be worrying to hear you say “nope” to that one. I wondered more about whether it changed or redirected the focus of your work.

Do you mean the Black Lives Matter movement? Or do you mean the pandemic? Or the shaky economy? Or the ongoing degradation of democracy? Like I said, completely impossible to be unchanged, and I’m definitely processing it in my work and life.

Yeah, exactly. Can you give an example of how you incorporated some of those issues into your latest work?

I usually lean away from quick, overt political responses in my work. There is certainly a place for satire and sensationalism, but I think my work tends to be better served by allusions to topical issues than direct assertions. Power structures have been a central theme… and it certainly feels as though those remain well worth prodding in this era. I listen to audiobooks while I paint and am currently three-quarters of the way through The Power Broker— all about Robert Moses’s notorious reshaping of New York City at the dawn of the car era until the ’60s.

And, surprise surprise, the very infrastructure of the city—many of its roads and parks and bridges—was constructed with racism and classism so sturdily that the repercussions still haunt NYC a century later. So much was built in pursuit of power and to curry political favor, without considering the needs of the city’s inhabitants—immigrants, the poor, and people of color, in particular. This is not unique to New York, of course. It’s not unique to the twentieth century. It’s only one example of many in which an ostensibly tremendous feat—I mean, look at the city from a distance and how could you not get a feeling caught in your throat—can prove to be a double-edged sword. In this case, it was both a triumph in the name of steel-and-concrete progress, and a terrible, terrible plight on a multi-generational human level. Not exactly sure where I’m going with this, except to say it’s all connected and feels relevant… and I’m thinking about these types of structures, and where I stand in them, when I paint.

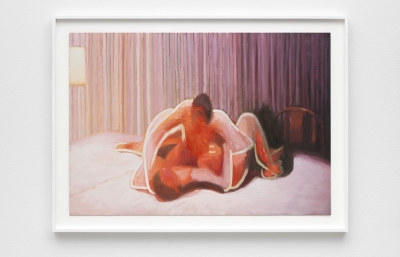

Sport Knot, Oil on canvas, 48” x 80”, 2020

You’ve mentioned in the past that your athletic background influences your practice. Can you elaborate?

My little sister is a phenomenal athlete, an absolute pleasure to watch on the field or swimming or dancing. I was more of a scrapper out there— you know, grit over finesse. I practiced and played hard. From early childhood, I was in the water for practice twice a day and at meets on the weekends, and continued this in tandem with soccer, until soccer won out, and eventually I was able to play varsity at university. There’s such a brutal regimen to it. It just kind of structured my life for so long. Eventually your muscles learn to comply and you ignore the part of yourself that always resists the onslaught. But it probably helped establish painting habits, yes.

How did you even end up going from being an athlete to making art, and how often do you come across artists with a similar trajectory?

Are the two paths that discordant? I guess I was always into both. I think painting and sports could kind of be siblings. You’ve got the hand-eye coordination component in each, mental diligence, repetition of a physical task to build muscle memory. And all the while, your mistakes and shortcomings are laid bare in front of your teammates or peers—in the name of constructive criticism, or because your coach is a sadist and you are a masochist. You have to be a bit dense to keep going. And at some point, you have to shake off the critical eye of the coach or the weight of your own judgement and trust your body’s current. To me, they both provide a release… a fierce, kind of ecstatic labour that belongs intimately to the body.

In soccer, like art, you have to look at a big field that is constantly shifting and figure out where to put yourself in order to best receive and then pass the ball. They are both a conversation, a series of give and goes.

A swimmer gets fast with one kind of stroke, and the next year she’s confronted with two brand-new, swollen bumps on her chest. Suddenly, that technique no longer serves her and she has to adjust. I think the same mentality is required of an artist. There’s a need for nimbleness in making and thinking to ensure your conceptual desires—and your more concrete objectives—align with the way in which you go about bringing them to life… Oh, god. I’m that guy with the sports metaphors!

Yes, you are and I love it! Those are such great comparisons and parallels. So, since you’re so good at it, then who would be the coach in the art side of the story?

I guess while in school, profs and peers? Then, hypothetically, the critics, if you’re lucky enough to get something critical out of them. The audience—whether actual or perceived. The people who’ve been generously brutal… the deliverers of tough-love in your story often become the people whose opinion you weigh in your head. And I guess when you’re alone in the studio, you become your coach. Scary thing when she’s in a mood, though.

Your last body of work was built from your perspective outward, mostly based on personal experiences, memories, and feelings. Is this still the way you go about it?

The last body of work had loose ties to personal experiences—largely teenage ones—but no knots holding them there, if that makes sense. I’ve got this decade gap between my adolescent self and so much new content and refurbished memories to throw at that poor sucker. I puzzled over teen movie tropes until I was older—teen movies are not made by teens, but by adults looking back, right? So I get to go back to visit Heathers, Mean Girls, Bring It On, Wet Hot American Summer… smart movies disguised as dumb ones, and more contemporary ones like Lady Bird or Call Me By Your Name, and think about this funny snake eating its own tail scenario. The teenagers who consumed the former generations’ projections and altered memories—they grow up and make movies about their own experiences. Which then helps shape the next teen generation’s understanding, or misunderstanding of itself. It really feels like time travel to me.

What's with the cars in your work?

I thought you’d never ask! Ha ha. Well, the car… anything can happen in a car. In a larger sense, it’s a North-American coming-of-age symbol—and sort of tucked right into the trajectory of modern art. There’s this obsession across cinema with it too that aligns with real life somewhere. Bad guys chasing bad guys… violence… teenagers. You hit 16 and bam, you do whatever you can to get your hands on a puttering hunk of hand-me-down metal to just get you outta there! And suddenly the world opens up. It’s a room you can speed around in, where you can collect private conversations. Sneaky sex. It is safe until it’s not. You can stuff so much in a car. And with all that, it’s such a kind of perfect metaphorical and compositional armature for a picture.

So, teenage-hood and cars… this has been some of the enduring subject matter, but I definitely play house with composition—start with a foundation borrowing from stories, news, lyrics… insert a ghost story here and there from paintings past. And once the beams are in, I’ll give ’em a little whack and hope they’ll stand up with the full force of the painting’s inhabitants and all their junk.

I loved how some of the works are connected to each other, depicting the same scene from a different angle or slightly different time. How did that concept come about?

Honestly, at first, mostly out of necessity. Trying to sharpen up a completely invented space can be frustrating, especially if you’re building form and trying to coax paint into light. After spending so much time willing that space into existence, I’d just pivot slightly in the scene, imagine turning the viewers’ head to the painting’s periphery. That way, I can borrow the feeling of that space and push it into the next painting. Like eliminating one variable. Then each painting has space to change but also something to hold on to. It really just helps me move through ideas without having to go back to the dark, you know?

And clues from one painting might inform another later on, or give light to one I painted years back, or solve questions whose answers might currently be remote to me. Nice sometimes to defer to a future version of myself who has her shit figured out.

“The dark” being having to think of what to paint?

The dark being the place behind your eyes before the world shapes itself in paint.

So, is that how you go about making a painting for a new body of work?

Sort of. It’s all evolving slowly. I was listening to a podcast that described the Supreme Court making moves at snail-speed. If you have a lifetime appointment, there’s decades-long three-dimensional chess to play… in that context, it’s incredibly unsettling to think that a small group of people have so much time, and ultimately power, to warp the country to their will. But I’ve been trying to apply the concept of snail-speed to my work. Thinking about it as a slow, lifelong thing.

You seem to be focused on rendering surfaces—aluminum sinks, gravel, droplets of water, hair, skin. Why this interest in creating such tactile surfaces?

Before I start a painting, I take the idea and figure out of the gist of it in a drawing. That’s like establishing the power lines—or like I said before, the foundation of the house of the painting. But then it takes time to come into focus. It’s like being in a dark room and willing it, or feeling it into existence with your fingers.

Maybe it’s an argument for a specific kind of experience. One that's full, unfolds over time, sometimes uneasily. A 10K compared to a 50-metre dash. There’s nothing wrong with fast-twitch muscle paintings… it’s just not what I’m doing. I want to make a painting that acts on the viewer like a slow-release pill.

I’m holding onto an archaic medium that some might argue is still dead and just experiencing a temporary resuscitation. But I can’t get the feeling I get looking at a painting—that really works on me in such an abrupt, physical way—anywhere else. So imagining there isn’t room for more of that feeling, or no possibility of pushing its evolution or proving it’s worthy of pursuit…what a brutal place that would be.

I am not after a painting that looks real, I just want it to feel sharply familiar. I think about authors like Haruki Murakami or Jennifer Egan who can express in one sentence what most people can’t get at in a whole blabbering book. In real life, I’m probably more of a whole-blabbering-book person. But I’m certainly trying to find— and make—sentences inside paintings that can encapsulate a feeling you’ve experienced many times—that you know in your bones, but that shrinks away whenever you try to put a name on it, kind of like a dream does. I am looking for a painting that has so much in it that it sticks to your ribs and rides along with you even after you’ve moved on. Did I actually answer your question at all?

Perfectly. So, what are you hoping for in 2021?

I’m hoping to step into my thirties… gracefully? I want to learn how to sew my own clothes and I’m hoping to be able to dance in an all-night techno rave. And see my family again. Art-wise, I am excited for my solo show in Brussels with Super Dakota in January and some other semi-secret projects. I’m also hoping to become a little more mysterious, you see, so this is a start.

Follow @danicalundy for information on her upcoming shows // This interview originally was published in the Winter 2021 Quarterly