Daniel Rich

This is Then and This Is Now

Interview by Evan Pricco // Portrait by Kyle Dorosz

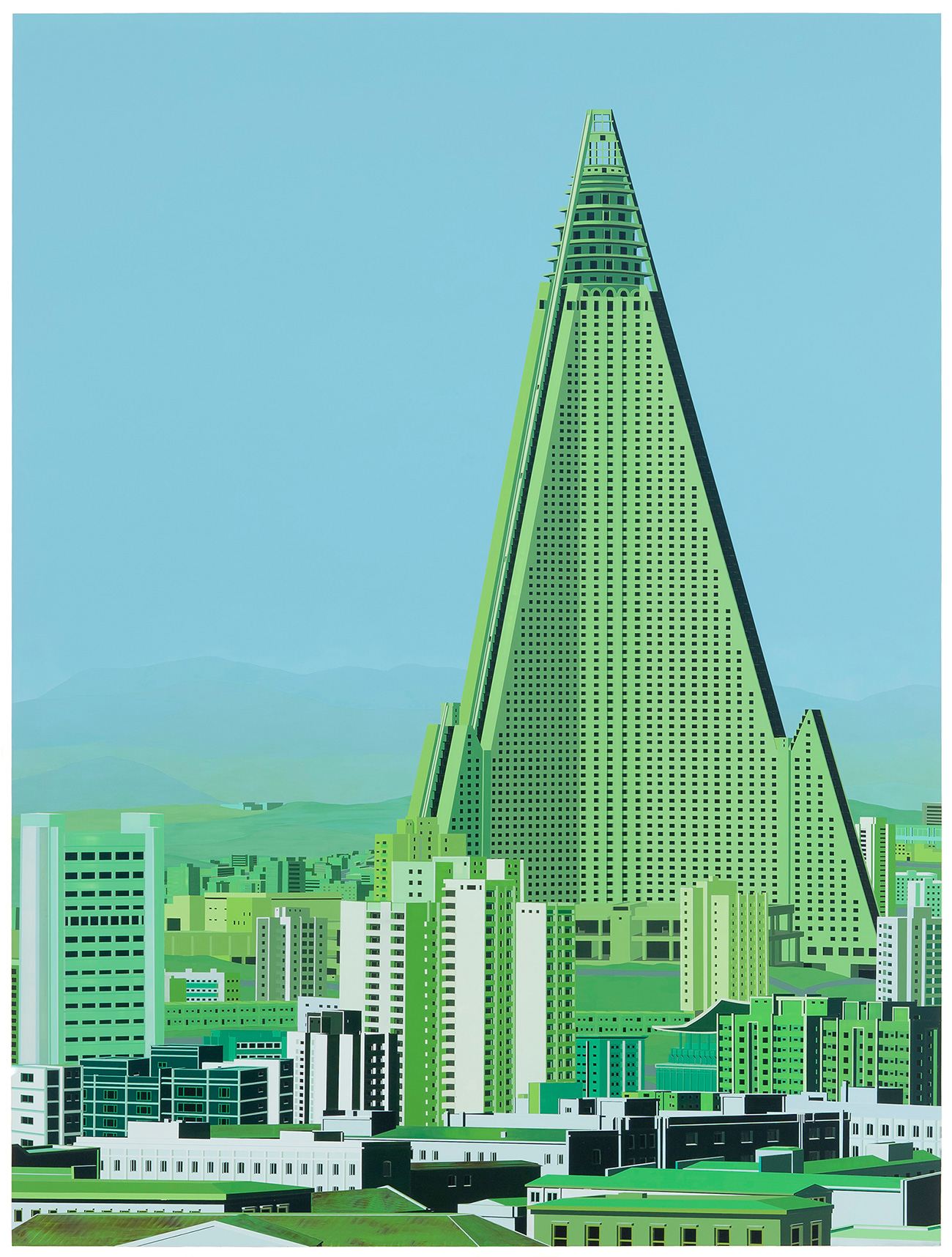

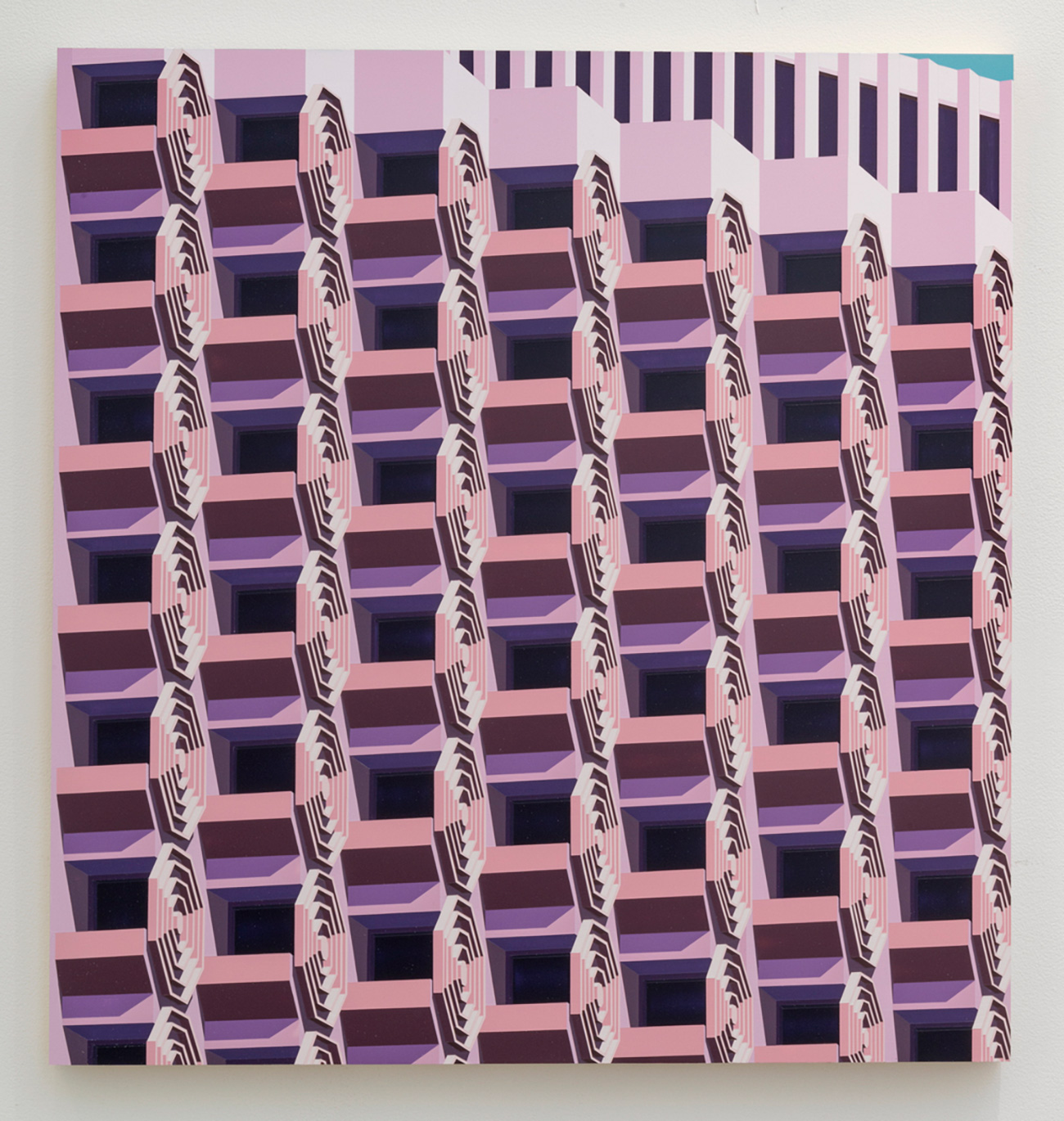

The city is a living, breathing entity, and from above, the perspective that Daniel Rich approaches in his image-making creates fluid interpretations of the landscape. Am I looking at New York City? Is that Tokyo? Does it matter? As Rich puts it, his overall goal in making works based around cities and architecture is to have “a dialogue about changing political power structures, failed utopias, the impacts of ideological struggles, war and natural upheavals.” Every city’s history relates to change, failed ideas and overlapping architectural eras mixed with historic relics and smart design. In his paintings, the NYC-based, German-born artist has created a language that functions as both window and mirror, to view the city as a vital portal of the past and future.

Evan Pricco: After all the hustle and bustle of NYC, you are going to be in North Carolina for a bit preparing for the next solo show, right?

Daniel Rich: I’m in a place called West Jefferson, North Carolina. I think it has 1,500 people living in it, barely even a town. It's in the Appalachian Mountains, basically western North Carolina. It's very beautiful. My wife's family owns property here, so the space was just available. We're just going to live here and see what happens.

Although you grew up in Germany, you lived in South Carolina later, and then you went to New York City. Give me a little bit of a background of how you got to where you are now.

Yeah, I'm sort of stateless. My parents are from London, but I was born in Germany because my dad is a hematologist with the Red Cross and was based there. I lived in Germany until I was 19, and then my dad took a new job in Columbia, South Carolina. I had the choice of staying in Germany or coming to the states. In Germany, I was skateboarding, painting graffiti, and just not really focused on anything in particular. Because things weren’t looking so bright for me, I decided to move to South Carolina and did a year of high school there.

Everyone was applying to college and I decided to apply to art school because I always liked to draw and, like I said, I had a background of painting graff. Because South Carolina was such a big culture shock for me, I went to Atlanta to this place called Atlanta College of Art, which doesn't exist anymore, but there was an art school at the time. I was going to study graphic design but then immediately got into painting and printmaking. I didn’t know I would be into that! And then something odd happened where I got some awards, so then I started thinking about graduate school. I wanted to get out of the South. I wanted to live in a city again, one that had a river, transit system, and stuff like that, and for some reason, I decided on Boston. Then I just kept it going. From there, I moved down to New York and just kept working. Maybe the last five years or so, I've been able to support myself just with my work.

What was Daniel Rich the graffiti writer like?

I was very tight. Actually, when I moved to Atlanta, REVOK was still there, and so I was psyched to see graff on such a level. That was also more of the scene in Atlanta. It was more about painting productions, and then the illegal spots were more like silver pieces. We did a lot of highway spots and things like that, so that's what I did most in Atlanta. When I moved to New York, I didn't have the energy anymore to stay up late. I didn't really paint. I was just more of an observer of graffiti after that.

It makes sense because you have such an observational eye for a city in general. I always noticed that people who did graffiti at a young age tend to look at the city differently as they get older. It works with skateboarders, as well. It seems as if you gain a perspective from graffiti so that you understand structure and mass in a certain way.

That and growing up in Germany, being really into history and seeing how history and landscapes aren’t there anymore because of war and political change. So, Germany, skating and graffiti led me to being into architecture or just having an appreciation for the built environment. Seeing how buildings connect with each other, I've definitely carried that through into what I'm doing now.

This probably isn’t the first time you have had heard commentary that in your paintings, it's like the world has been abandoned. There's something about that absence of people that has a doomsday feel, like what's left behind when we leave.

It’s not necessarily something that I do on purpose, but, for the most part, I do try to make them appear somewhat timeless by editing out references to people. I do know that they come off as being "the day after" kind of look. It’s interesting that I'm not really that aware of it, but I like what people read into them on their own.

Depending on where you are in the world, some structures themselves have an inhuman concept, almost like they've come from a different planet and were not positioned organically. Or the way so many buildings and styles clashed after cities were rebuilt after WWII, especially in Germany.

So much in Germany was rebuilt and was new, but was also made to look old. You get this ugly modern look that doesn't fit with the rest of the landscape. I guess what I'm really interested in is how history is recorded through architecture, while paintings capture a moment in time. Maybe there's something uncanny about the scene, something strange. That's something I do, add a weirdness to the image, something that's a little unsettling. I look at it like a Trojan Horse because the subject matter, I would say, is 95% politically motivated. Maybe you'll find out the title of the work, the city, and that might introduce some other thoughts into your head as far as what the painting is even about.

Let’s cite an example; for instance, your painting, Athens, from 2017. Talk about the way you choose an image, what your motivations are when picking a city.

I had gotten into the Athens cityscape because Athens is this iconic place, the birthplace of democracy, and has undergone so much change in the course of its existence. Also, the contemporary face of Athens is a direct result of the clash between capitalism and communism, because after the civil war in Greece in the late 1940s, it was either going to lead toward a communist system or capitalist system.

Basically the government prevailed and wanted a capitalist system, and what they did was encourage this building boom in Athens in order to get the workers, the middle class, whatever you want to call it, on their side to vote for them.

They encouraged all this building in Athens, building which led to jobs, growth and people making money. It just so happened that the kind of buildings the state encouraged were really simple constructions, these multi-level concrete apartment dwellings. It's this early Modernist idea of architecture, but what was adopted in Athens is just super dense and looks like these stacked concrete blocks. That was the idea. I didn't actually know all of that. The initial idea was this clash of capitalism over communism.

What I do is I basically scour the internet for images that I can use. First, I blow up my source image to the size I want the painting to be and print it out on an oversized black and white printer. Then I trace the photograph on to the panel, which is completely covered with a transparent vinyl mask. The tracing is then tidied up with a black ink pen—that way I can fix perspective issues, edit and add to the image, and so forth. The line drawing on the vinyl covered panel is then "re-drawn" with an exacto blade—every line is scored with a knife. Once the line is cut, I can remove vinyl shapes to be painted in.

Once I have scored the line drawing, I mix as many colors based on the image I'm working from as possible—a color for each shape. The shapes are painted in with a squeegee by masking and re-masking over the scored line drawing over and over until every shape has been painted in. The large paintings usually have about 300 colors and take about 2-3 months to finish.

It goes without saying that seeing your work in person is such a different experience because you actually get to see those layers you are talking about.

Yeah, you can see it's actually painted and really cut with those raised edges where it's masked off. I do like that tactile quality, but they really flatten out when you look at them on the screen. They don't read the same way as they do in person, which is a good thing. An 8-by-8-foot painting takes up to 3 months of work to finish, which is ... a little long [sighs].

I love that sigh.

It’s meditative, but they do take a long time to make, which is the downside of my practice. I have had assistance in the past from interns, and it does help move me forward faster, but I'm a real stickler about stuff, so if the lines aren't straight, it's not going to fly. I feel like I’m the only one who can do the cutting part. People say, "Oh you should use a vinyl cutter, you should do this or do that," but I just can't see it really working out the same way as just doing them by hand. It would lose the personality. I'm just going with what I know for now.

So we talked about Athens, but you have a range of cities and structures you have addressed in your work. What else goes into the picking process?

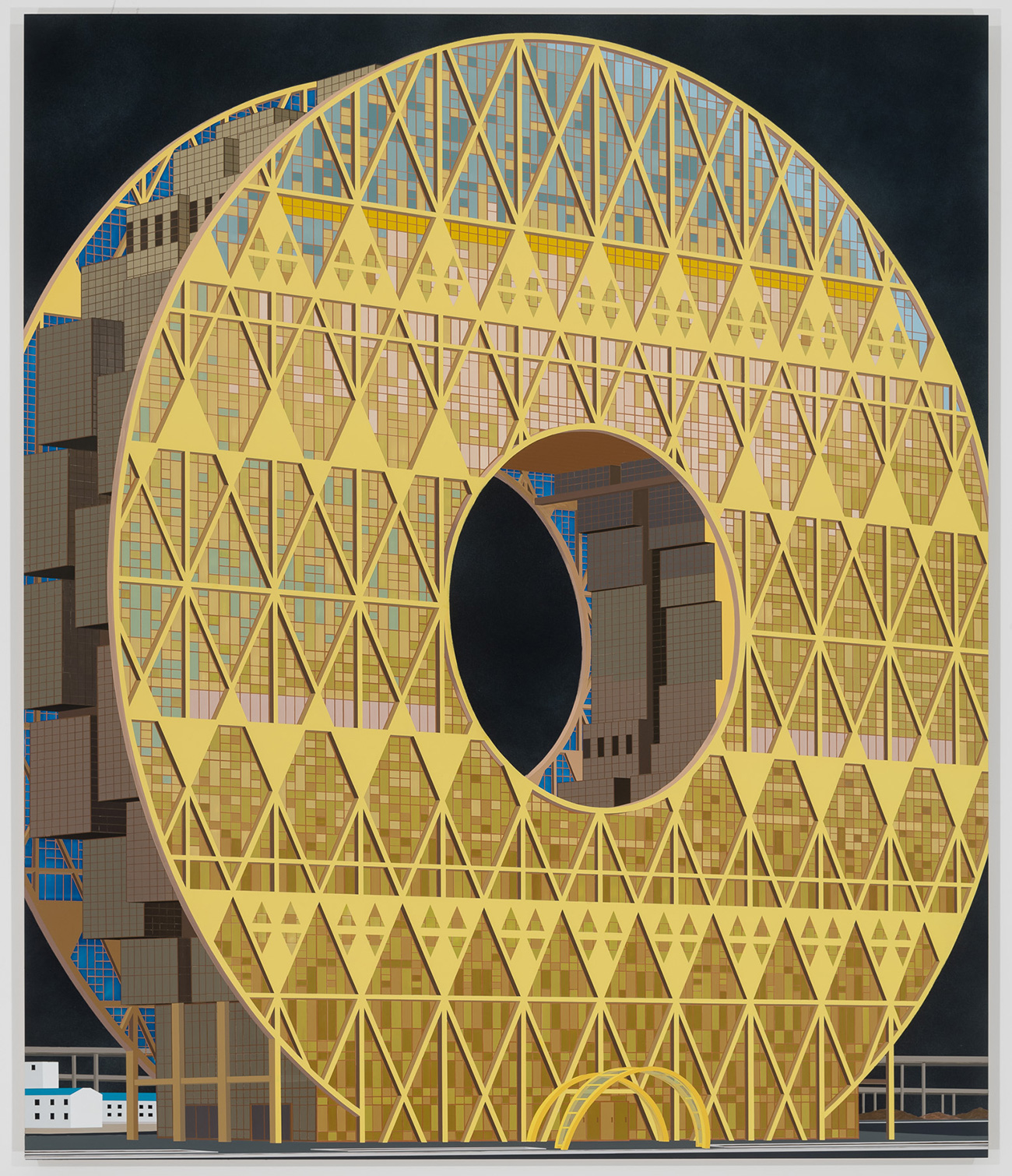

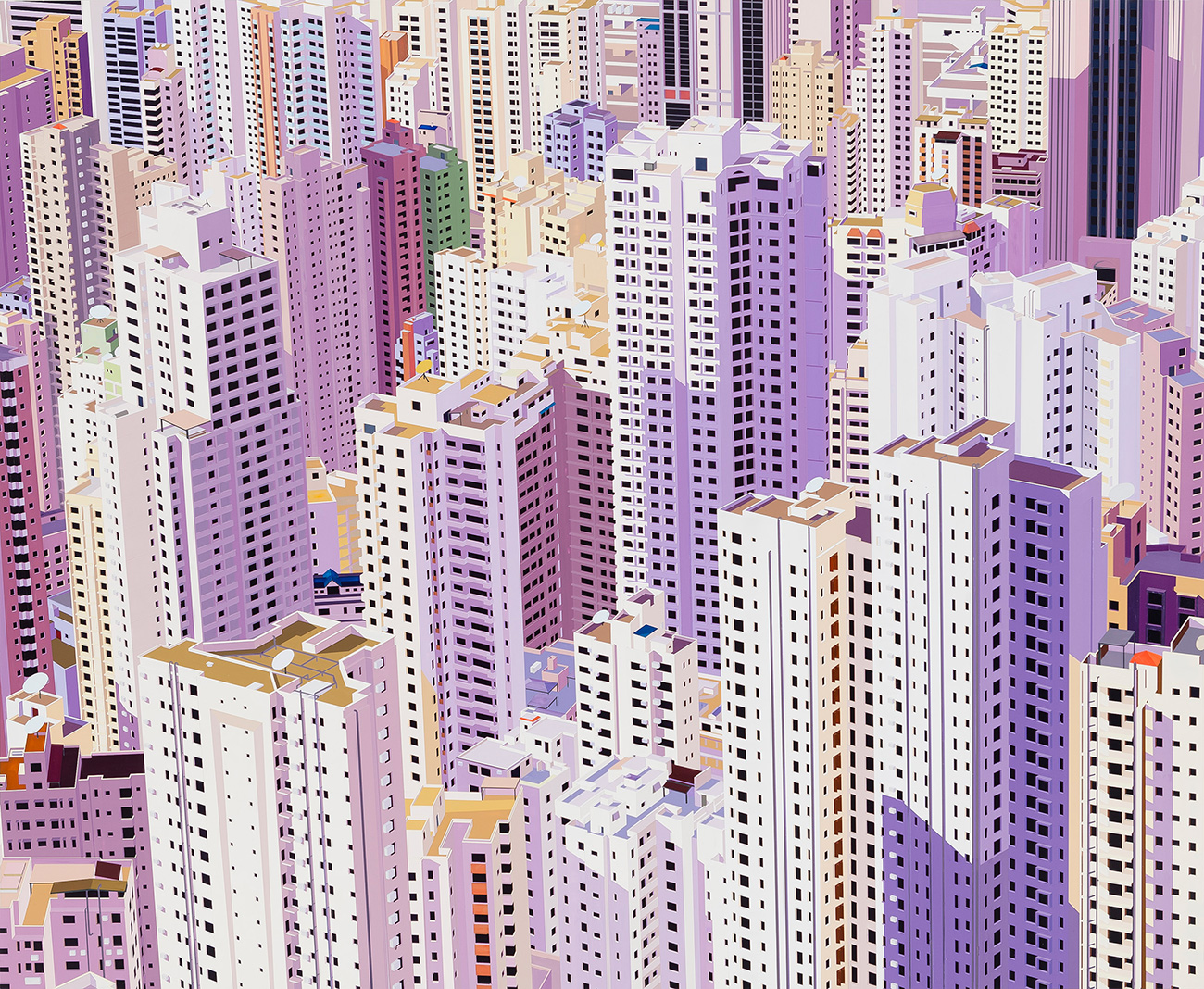

I'm a news junkie, so I listen to the radio a lot and I read the newspaper, and it's about the things that catch my attention. Then I try to seek out images that somehow reference that event or that thing that interests me. For example, the Hong Kong painting I made came about after the Umbrella protests that happened there that were about pro-democracy. I only started working on the whole cityscape works four or five years ago. Before that, I wasn't really doing these really dense compositions, it was more free-standing buildings. The imagery has gone down this road where it's really busy compositions right now.

You're not doing the postcard shots, which I think is very refreshing.

I definitely don't want to do the postcard shots. That was the thing with the New York City painting, too, the Upper East Side. When you think of NYC, everyone thinks of that skyline. And I don't want to do that. For that work, I took the picture myself, but I do prefer to work from source images just because it's part of the content. I find an image and it's super complex, but I get psyched about it because I see the possibilities of it being a good painting.

And you are working with nuance, often a complicated history or turning points in history. They aren’t as literal as seeing sights you are used to seeing.

They're definitely a lot more open ended in that way. My painting, Gamcheon Cultural Village, Busan, South Korea, looks like a Lego hillside painting. That was originally a refugee camp from the Korean War that's now become an artists’ village. It also underwent this transformation of being a place of despair, and now it's a tourist attraction.

When I first looked at that work, I confused it with something you might see outside out of São Paulo.

Yeah, it has a very different history but then adapted the same kind of architectural style. It's just out of necessity: we gotta build a shack and that's how we're going to build a shack. There's a hillside, they'll just climb up the hillside until they're at the top of the hill. I think it's interesting that we share these commonalities all over the world, that as humans, we automatically go to these same kind of styles of shelter.

The stadium painting is what first attracted me to your work. I have a fascination with empty stadiums.

That one was hell to paint! It’s really hard to paint the seats. It's based off the stadium called the Big Eye in Japan. I'm interested in the fan culture of soccer and how it also brings groups of people together, these very fanatical meetings, a “power of the masses” kind of a thing. A stadium can really exemplify that, and it being empty gives a moment of stillness that I like.

I personally got really fascinated with Olympic stadiums after the games. A lot of them aren't used for anything, and they just kind of sit there, especially in locations that aren’t as developed as Los Angeles or London. It's like Chernobyl, these relics left behind. It’s like perfectly sustained ruins.

Yep, instantaneous ruins. It will be ruined at some point, like these cityscapes I’m doing. All this stuff that we're building for specific purposes that's now just languishing.

Let’s talk about the show, because you are in North Carolina with a purpose.

Yeah, I’m preparing for a show at Peter Blum Gallery in NYC in early Spring, 2018. I'm hopefully going to have eight to ten paintings. Six of them will be large, and then I want to throw in some smaller ones.

For your sanity?

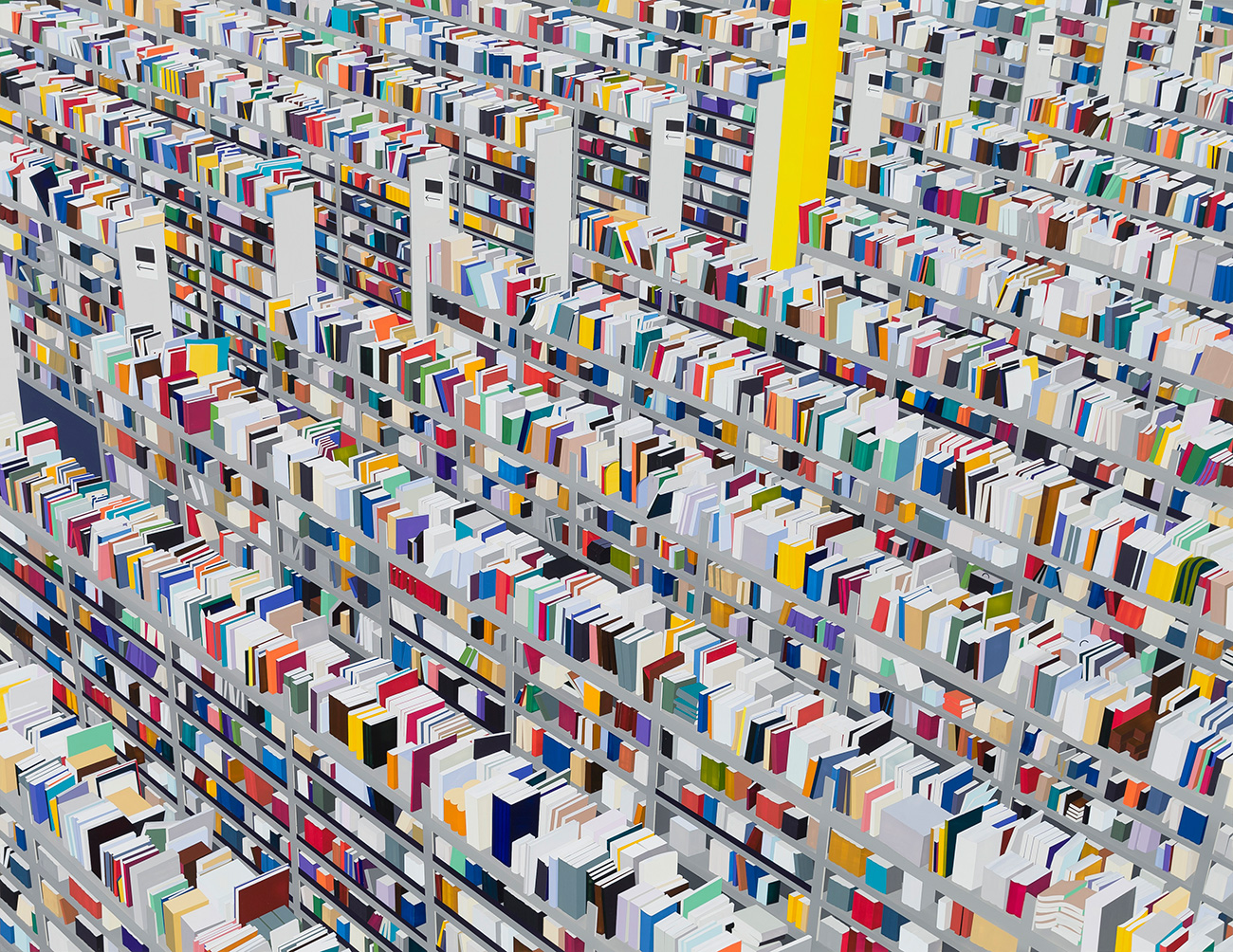

For my sanity, plus I like having smaller paintings; not only because they go faster, but I just feel like it feels good to make something more immediate. The show, I guess, is inspired by current events. There's all this talk about globalism and anti-globalism, and just the fact that we have already moved past that point of being anti-globalism, I think. We are all in this world together, we're more connected than ever. To be anti-globalist at this point in this country is just ridiculous. That's what the show is going to revolve around. I’ve been working again on the Amazon fulfillment center works, and there will be a couple of those.

What I like about an Amazon fulfillment center is that people always think it's a library. It's not a library, it's a warehouse! That made me think about how Amazon is like a future library and how libraries are sort of national heritage sites. For Amazon to take over this role of being this supplier of the written word I think is really interesting. Also, there's been these key events in history involving destructions of libraries, like the Nazi book burnings and ISIS destroying libraries. I got it in my head that I would make this painting of an Amazon warehouse that was looted or destroyed and then place that next to an image of a pristine one.

I’m working on another, bigger Athens painting, I have a big, empty stadium that's based on one in North Korea. I'm doing a painting of worker housing in China that's also like a big cityscape. I like working with these seemingly unconnected images. But then they do all connect on multiple levels, just not overtly. I have been told that I should make more theme-based shows, but for some reason, I can never quite get into that idea. I don't want to make a show that's all the same kinds of building or towers, or this or that. That kind of bores me. History is too chaotic.

Daniel Rich’s next solo show will be on view at Peter Blum Gallery in NYC in April, 2018. His book, Windows and Mirrors, is available at danielrich.net.