Tell me more about how using cotton and other materials supports the content.

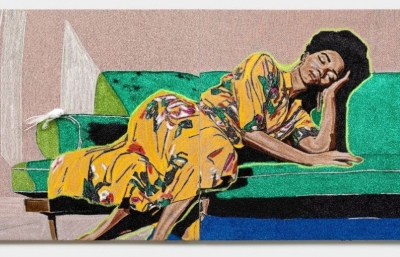

Materially, it is mostly cotton that does that, and I’m intentional about using it because of its realtionship to Texas, to this country, to slavery. Even beyond slavery, I have family members who are still alive who grew up picking cotton, so it feels important to use those materials if those histories are embedded within, and if it can be any kind of homage to them—to elect to use it, versus it just being this thing that is impressed upon you. It’s idyllic, of course, but it feels important to have that small tribute embedded in the work.

It’s a big tribute! Do conversations about your work bring up moving moments?

Beyond weaving, one of my favorite things is interacting with folks around the work. I love being able to share particular stories or images, or point things out about the work, and hear people talk. It gives me a lot of joy and a chance to really dialogue with people.

A lot of moments that stand out are around spiritual things, which is somewhat embedded, but it’s often not something people want to talk about in a fine arts context, so I typically don’t.

Some people have asked about a very specific story from the Bible, or said the work feels biblical, and the first few times it happened, I didn’t feel good or bad about it, but it was interesting. It wasn’t surprising that someone would say such a thing. Growing up Southern Baptist, there were so many of these stories just baked into my mind, even though they’re not things that I’m anywhere near thinking about at this point in my life. I would start to see it, and have more conversations about that, to the point where I decided to intentionally mine some of the imagery. Instead of it being this thing that came up, I could take control of it and embed my own content on top, as opposed to using my content, and then finding out that it invokes something else.

A lot of the later images, like the horses, the snake and the hare, were moments where I was deciding to take these animals with particular biblical symbolism, and think about what I actually want them to say and do. I was using these animals that, in the Bible, were either representing evil, or weren’t things you were supposed to eat because they were unclean, and thinking about how to extrapolate and change those ideas, making them into things that talk about my own experience as a queer person.

And then how does it complicate the situation if I’m thinking about this animal as a means of self transformation, or as a stand-in for any kind of celebration of myself? What starts to happen if people read into these biblical storylines, and the horses were fueled by these ideas of the apocalypse, and the fact that, on any given day, it feels like the world is coming to an end because of how crazy it is?