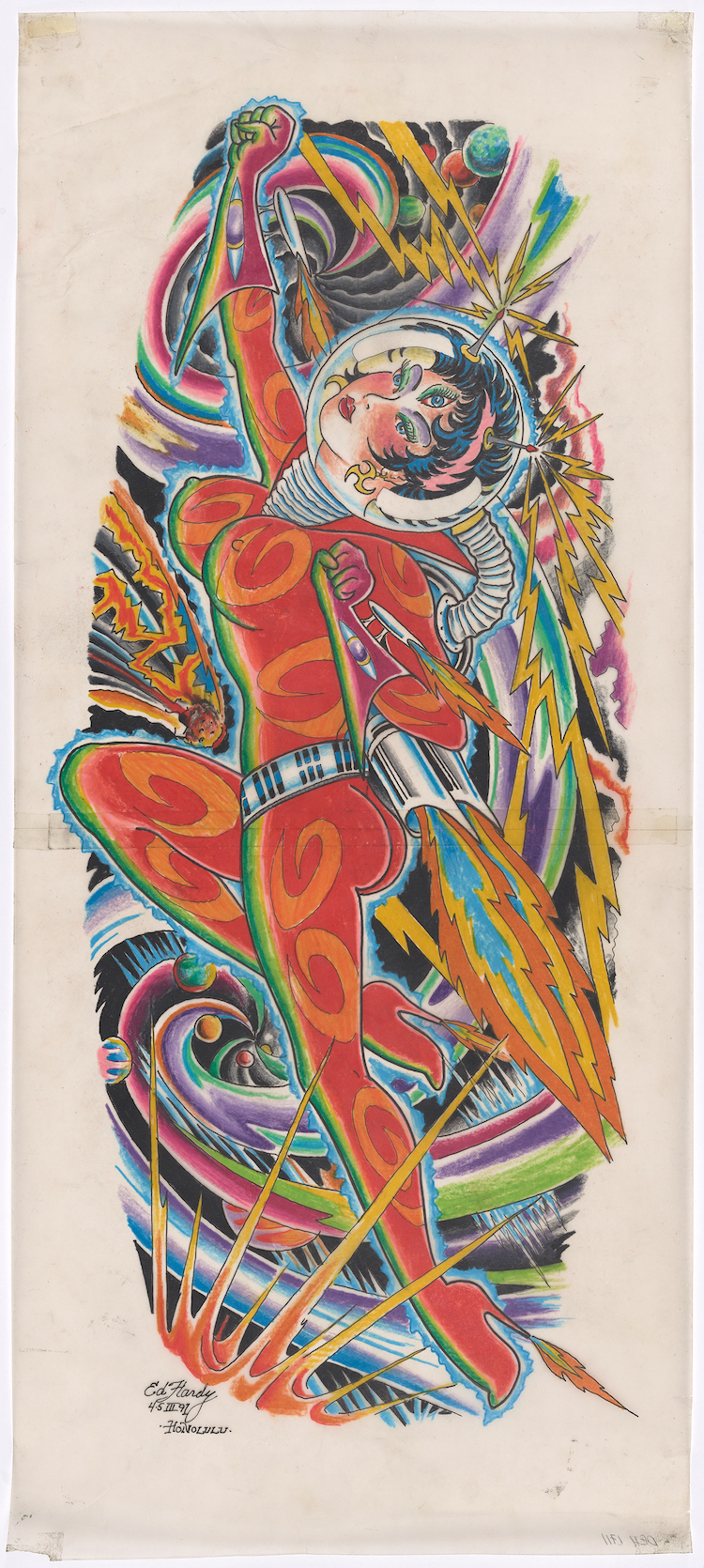

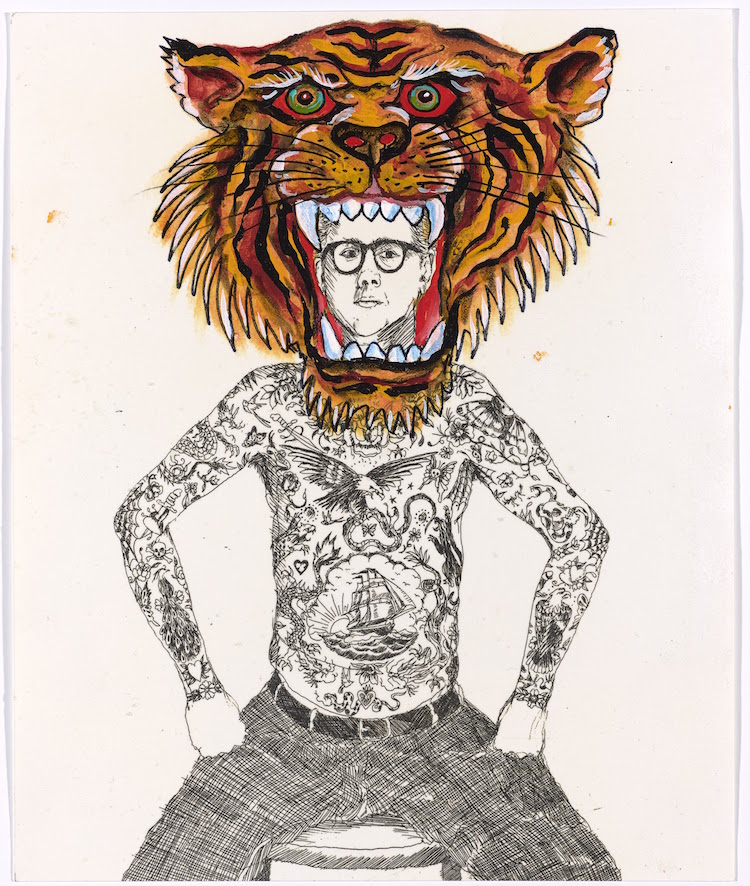

Ed Hardy

Deeper than Skin at San Francisco's de Young museum

Interview by Gwynned Vitello

2000 colorful dragons cavort along the 500-foot long scroll painting that ripples through the Deeper than Skin exhibit of Ed Hardy's work at the de Young museum. Suspended from the ceiling, they really do ripple, and yes, in the fullest meaning, they are swell. So is this retrospective of an artist who dreamed beyond horizons as a kid growing up on the beaches of Southern California, later discovering ancient Eastern culture when he studied in Japan. We sat down to talk in the offices of the Achenbach Foundation where, as a young man, he studied printmaking, and where I learn about the women who mentored him, the books he has always treasured, and the giant waves he still seeks in a life guided by the joy of discovery.

Gwynned Vitello: It all started with drawing, didn't it? The documentary, Tattoo the World, describes a kid with lots of freedom and energy, and I wonder what you were sketching at that young age?

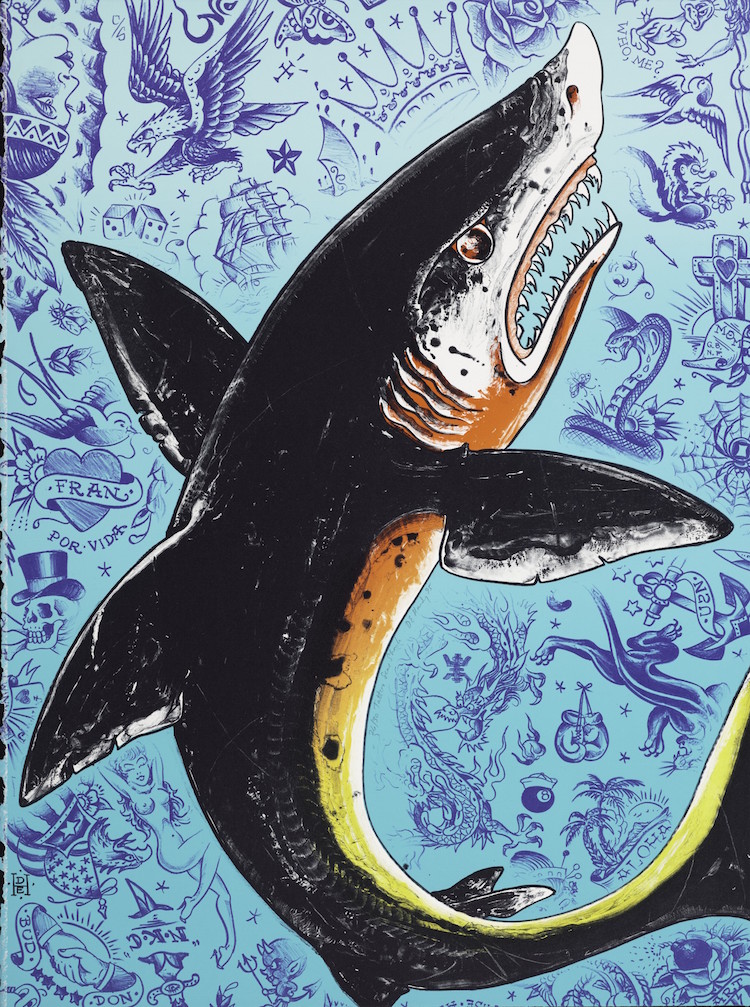

Ed Hardy: When I was a kid, I drew a lot of ships. I was raised in Corona del Mar, and with the bay, the shipping, the sailboats, I was completely entranced with pirates and old clipper ships, that kind of thing. I still have a copy of a book called Pirates, Ships, and Sailors that was put out in the early '50s when I was six, seven or eight. It really showcased the massive ships and pirates with tattoos and all that stuff.

Of course, pirates would have tattoos!

Yeah, it all kind of fit together, and it was great being raised that way, because it was really idyllic in those days, very small and low key. I was about five blocks from the beach, so I grew up in the water.

Not monsters or cars? I thought maybe some hot-rodding had snuck in.

Initially, it was the seafaring stuff, and then the cars. That was a visual experience for me because I never had a fancy car. But the beach at Corona del Mar was really beautiful and drew lots of people from LA, so in those days, when the customs and hot rods were really flourishing, you'd see so many of those in the parking lot at the beach. I remember Dean Jeffries and all those crazy painters, guys who were painting the switchers and stuff. I'd watch those guys at the expos who air-brushed custom shirts for people at the car shows.

I knew you did that as a young man, but didn't know where you got the inspiration.

Exactly, because in those days, nobody had fancy T-shirts. They had just white T-shirts the guys brought back from the army. People would get all kinds of crazy images painted on them, as well as cartoons of their cars. So all this stuff about personal art is about people expressing their taste and interests. I'd see people on the beach with tattoos too. In those days, if you had a tattoo, you'd basically be in the service or been in jail.

So, you just started out with a pencil and a variety of influences.

My mother encouraged my drawing. She figured I had a talent for that and would make notes to go with the stories I related to her about my day. I'm pretty sure there are some drawings I made when I was three, so you can see I started really early. With her encouragement, it was the main focus of my life. It's still the one thing I'm really good at, you know?

You have said that you blanched at the “white bread '50s” but it sure doesn't seem like you were repressed or regimented at home.

I wasn't, and because I could see all the popular culture that was around, I was fascinated. It's not like my mother was far out or anything, but she loved the fact that I could draw. She loved art, and Laguna, just down from where we lived, had been an art colony since the '20s when they had the Laguna Beach Festival of Arts. We would go every year and see the Pageant of the Masters. I had good support at home.

There was stimuli all around you, and it sounds like you were very drawn to the exotic. But unlike our friend Robert Williams, the admittedly rebellious Robert, you weren't exactly a rebel renegade.

I was a bad boy very mildly. Yeah, I started smoking when I was 10, but no. I was just crazy about art, I thought it was magic, you know, to be able to make these things.

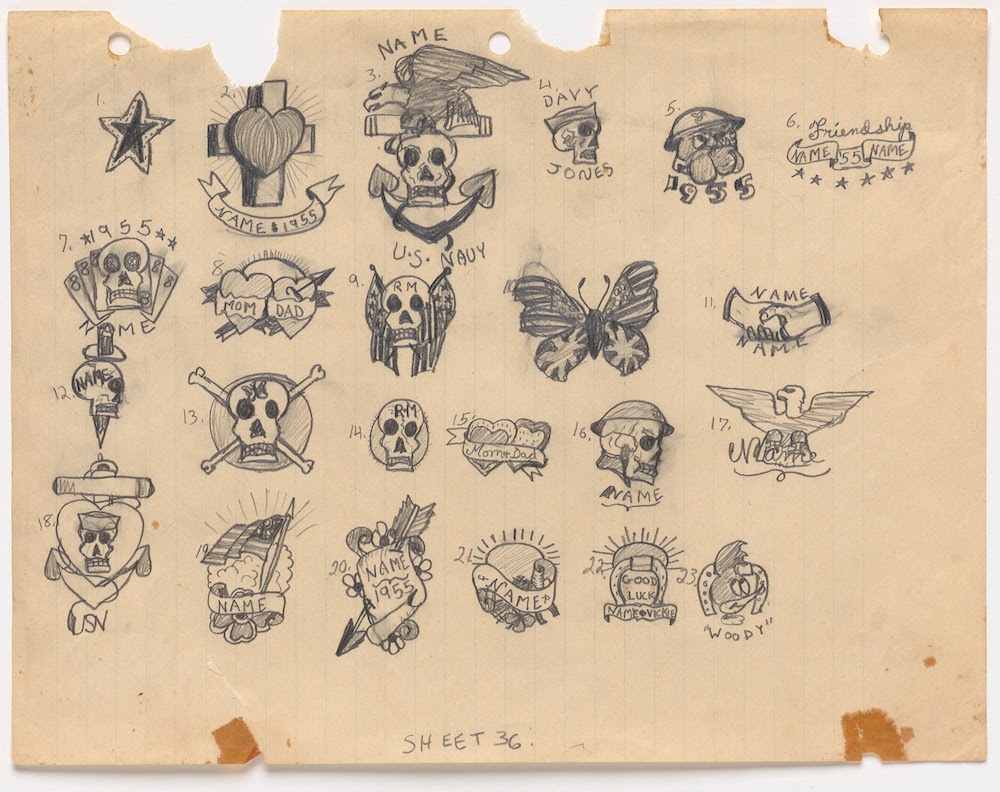

Bert Grimm's shop was your first real exposure to the practice of tattoo, right?

It was the biggest tattoo shop on the pike and, in those days, tattoo shops were pretty rare. There were none in Orange County. I think when I got in the business in the '60s, there were probably 500 shops in all of the country. Now I think there must be 5000 and counting. But I was fascinated because my best friend's dad had some tattoos, and I thought, “That's really cool.” My friend Lenny and I started drawing tattoos on neighborhood kids and tried to get them to pay, like, three cents. We just wanted to do the tattoos, you know? There were kids walking around town with these tattoos that weren't real. We did it with pens in a room in my house we called the den, where my mother did her photo coloring.

I didn't realize your Mom was an artist.

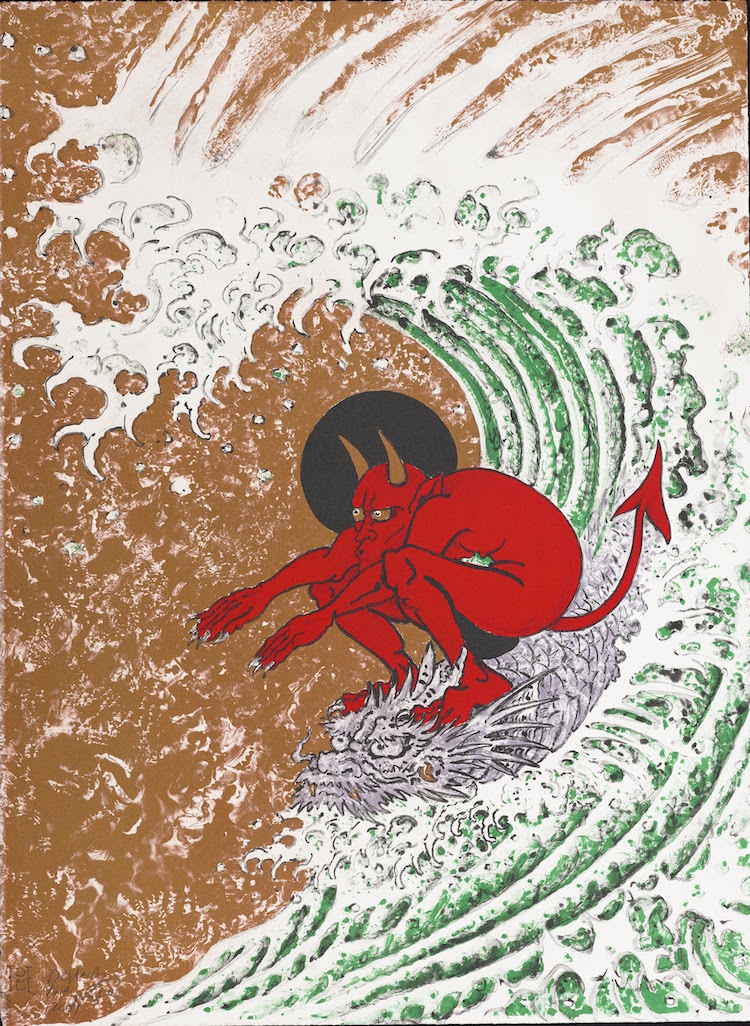

Yeah, it was a side job, she did hand-tinted photos. My dad left to go to Japan when I was seven. She figured after a few years that he wasn't coming back, so she divorced him. But he kept in touch with us and sent very cool Japanese stuff, things that were exotic to me and fueled my interest. I still have a real cool dragon painting on silk, and it's up in my studio. In fact, he sent a book called This is Japan, and on the cover was a Hokusai great wave, that famous print. I was like, whoa, and that fit right into my fascination with surfing.

Which is another major influence on your life and art.

Those were key influences, and as I got a little bit older, I got interested in beat culture and Buddhism. Then, going down to Laguna Beach where there were coffee houses, I started buying books by some of the beat writers. There was this kind of velocity of things unique to southern California that all factored in.

Especially surfing.

I grew up body surfing in Corona del Mar, and it started to take over my life. For a couple of years, all I drew were surfing pictures, and I remember the art teacher always saying, “You could do so much more than these surf pictures,” while I was saying, “Yeah, yeah, that's what I want to do.” Then when the light flipped on, I really went for it. She encouraged me and told me about a lot of artists I should take a look at. I remember getting my first Picasso book at 16 or 17, and thinking, “No wonder this guy is famous. This is how you should make art. It can be anything.” I didn't feel like there was one thing I wanted to do, I wanted to explore it all, you know?

She recognized that you would enjoy books and writing, but I'm guessing that most of your friends didn't share such enthusiasm.

No. I had a couple friends who were interested in art and could draw, slightly older guys. I'd draw surfing pictures and sell them to get gas money to go down to the coast. I was basically following this passion, and it was these strong women who were encouraging me.

Then I turned 18 and was draft eligible. That was a big deal in those days because you could get deferred if you were in school. It was the reality of the world we lived in, all things that shaped me. After a semester at La Jolla Arts Center, I went to Orange Coast College. I kept going to these beat book stores and reading some of the poets, and absorbing the intellectual background of these people, which was Buddhism.

I thought you were introduced to that when you went to study in Japan, but you were attracted to Buddhism before.

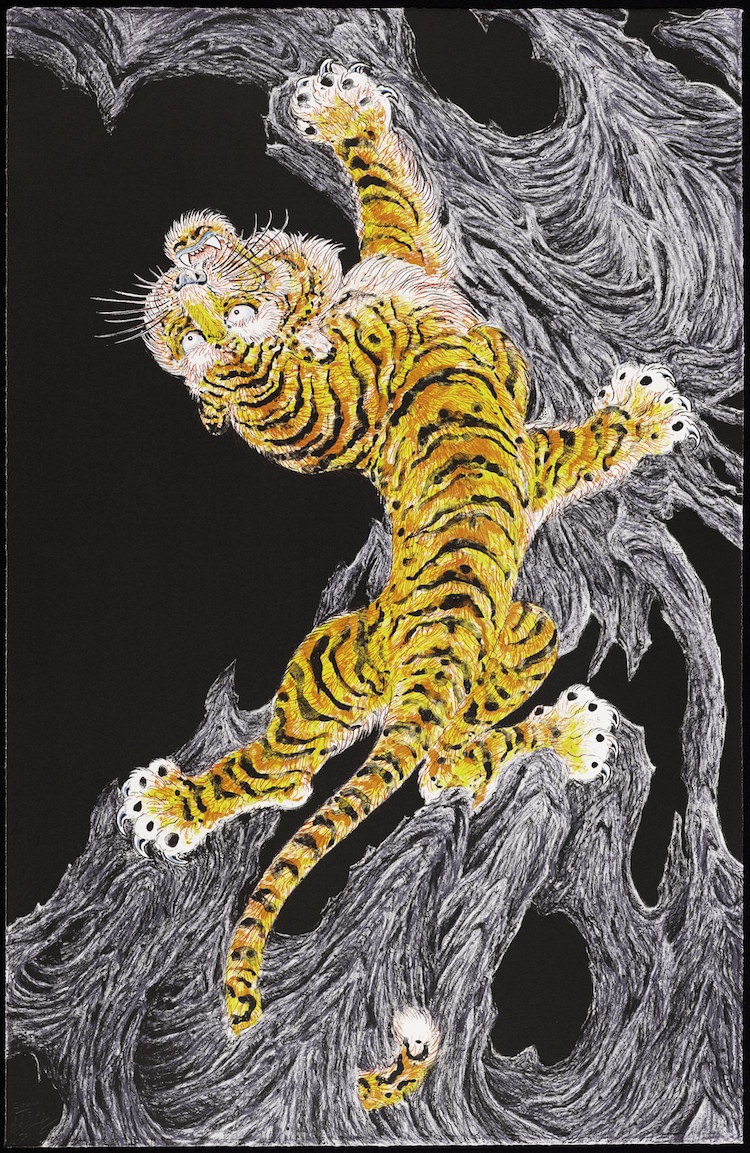

It started when my Dad would send back different things, and when I got into beat in my teenage years, I became interested in more than what the images looked like, but in the driving force behind them, which is based on Taoism and Buddhism.

I didn't realize it was so important to you. Is it still?

Sure! I mean, it's not like I go through the ceremonies, but it sure makes more sense to me than anything else. One's not right or wrong, but it's just a way of looking at the world, as opposed to Judeo-Christian, which was all that I knew growing up.

Let's get up to San Francisco.

Some friends found out about the Art Institute, and of course, I had always heard about the scene in San Francisco, so a buddy and I decided to fly up for the weekend. I remember it was a Friday night, and we drove straight to North Beach, and I was, like, “Whoa. Okay!”

You saw City Lights Bookstore, right?

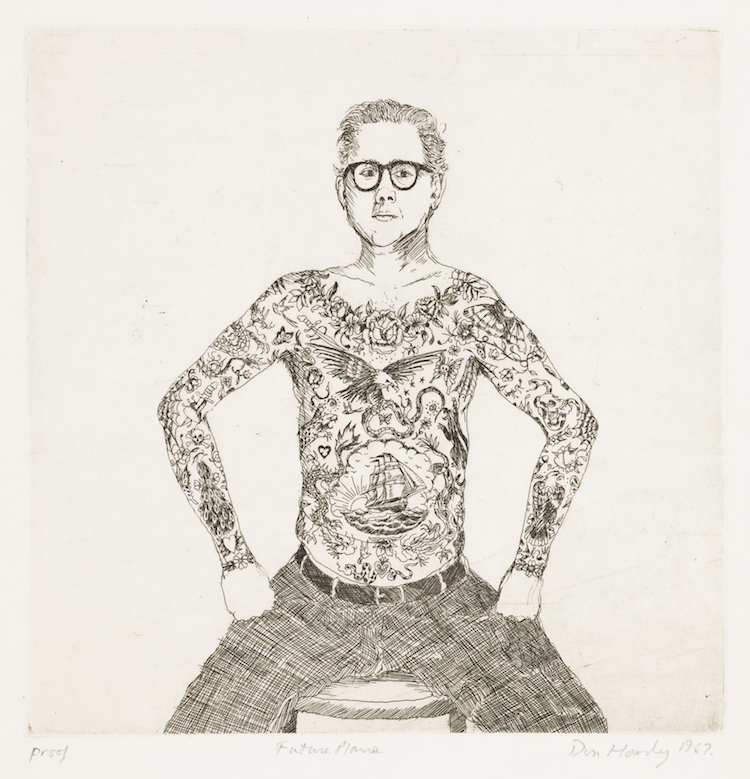

Yeah, everything. It was fantastic, and the Art Institute was fantastic. I realized that's where I really wanted to go. My mother helped me with that, and I got a scholarship after the first semester. That's where I got my degree in printmaking and etching. I was really interested in the idea of multiple originals, that it wasn't just one precious thing, but you could have a mirror image of a whole edition of the same image. I loved the democracy of it, you know.

I was studying a lot of classical printmaking, Rembrandt, Goya, and that's how I got connected to this place we're at. My primary mentor, Gordon Cook, taught etching, and we came out a few times to the Achenbach Foundation to look at classic prints. Maybe five or six of us would come out, and they'd bring out the Durers and Rembrandts and all that. It was fantastic to see these... these real prints that a guy printed 500 years before. It's not like a picture in a book. You get a tangible connection to a piece of art that person made.

Is that how the Yale scholarship came up?

In those days, the question all of us had after getting the degree was whether you teach and have summers off and be in that environment, or have a job unrelated to your paycheck where you could just do your art. I applied to Yale and was accepted, but I was just not interested in the kind of art that was popular at the time; performance art, conceptual art. But that was the time when tattooing came up and saved my ass.

The turning point!

I was at an art show at SFAI, and a buddy I'd grown up with showed up at the opening in his Navy uniform. I had actually hand-poked a little tattoo on him when were little kids, and now he says, “Hey, Don, I've got some tattoos!” It wasn't in my life at all at this point, but a light bulb went on, and we looked in the phone book. I remembered ads for tattoo supply catalogs from when I was a kid and saw the name of this guy Phil Sparrow, who was then in Oakland. He was closed, but we went to another shop and got a tattoo, then a day or to later, got another from a guy over there, Shaky Jake.

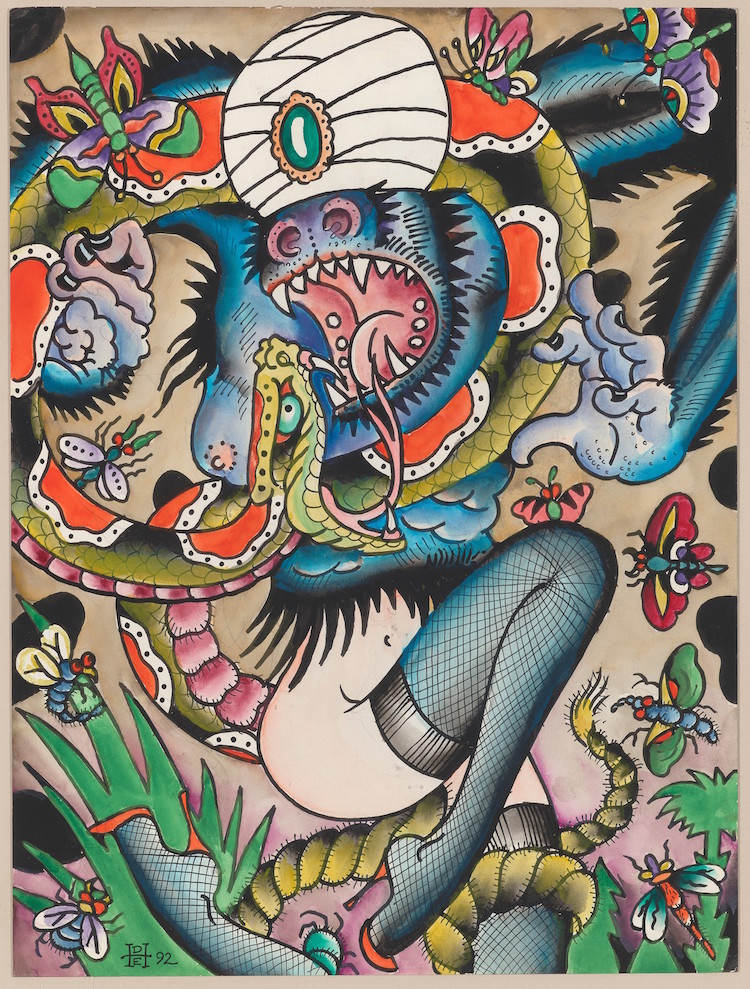

When I finally saw Sparrow's shop, it looked different; it was flash framed, more like an art gallery. I got a tattoo, then another, and on the third day, I told him that I was an art student. He showed me a book on Japanese tattooing, and said “This is real Art. Look at this.” I realized that this was a medium I could really develop, so decided against graduate school to become a tattooer. I basically bugged him till he gave me some help, and the first two or three tattoos I did were under his direction.

Followed by stints in Vancouver and Seattle, then San Diego, right?

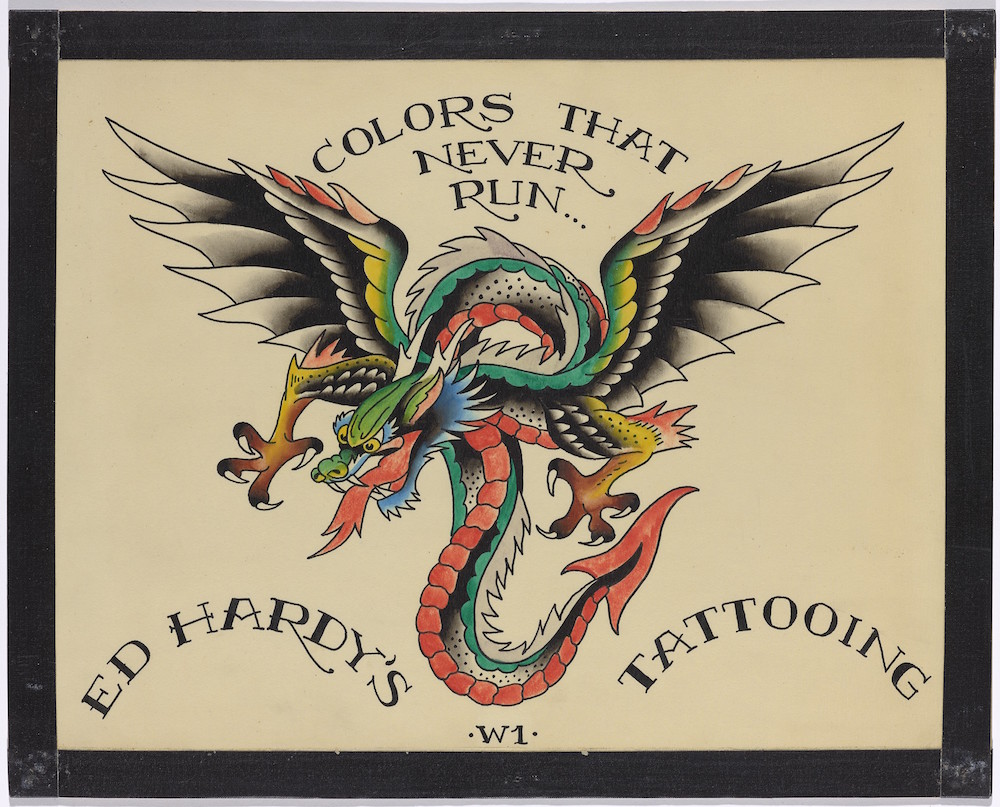

Yeah, port cities, which is where people were tattooing, and at Doc Webb's in San Diego, it was really like turning on a tap. Folks just kept coming through, and it was a really good place to improve technique and get used to the machine. But from the very beginning, I was encouraging people to get unique tattoos.

That they didn't just have to get what was on the flash.

The best metaphor I have is if you went into every restaurant and it was a Denny's menu, that's what tattoo shops were. There was a variety of skill and nuance, but basically one look, you know?

I worked for Doc for two years, operated my own for another two, and then was able to get in contact with a Japanese master who was corresponding with people in the West, and at the same time, with Sailor Jerry Collins who was basically the best tattooer in the world.

I didn't know he had a last name!!

Oh yeah, and that's how I got connected to the Japanese tattoo master Oguri. A few of us went over to Honolulu and all got a tattoo from him. I asked if I could come to Japan and work with him. I think he was just being polite and said, “Okay.” I did move to Japan but didn't realize how complicated it would be. These are all private shops, just word of mouth, not like there was a sign in front or anything.

And what was it like??

Most of the customers were Yakuza, you know, gangsters. I tattooed a lot of bad boys there. But it was fantastic, just incredible to be in that tradition, that deep kind of history and just being in Japan. When Oguri said, “Yeah, you can come over and work with me,” I was supposed to have this sixth sense that it really meant, “Come over and visit for a couple of weeks.” But I moved over, like, “Yeah, I'll stay five years and fit right in.” Totally naive.

But just before I went there, I had reconnected with this woman who had come into my shop to get a big Japanese tattoo on her back. The best thing that happened to me with tattooing was meeting Francesca. I was, like, “I don't want to lose this woman. I can't lose this life's dream to be in Japan.” I was there for maybe just two weeks, and wrote and asked if she'd come over if I sent her the airfare. She went, “Yeah, sure.” And we've been together for, I think, it's been 43 years.

As things developed, we realized it was not the thing to do to try and survive there. My dream had always been to have an appointment-only place. Francesca encouraged me to come back to San Francisco because this is where I knew I wanted to end up. She said, “You have to risk it and just open a private studio.” So we moved there, took a lease on a place, had just one little tiny sign outside the door, and it was word of mouth.

So, you and Francesca we confident you could make this work. What did you have to offer, and how was it different than other shops?

San Francisco, as king of the counterculture, I thought if I could make it work here, it would really work. People would tell their friends, and they came to me because they realized I could draw. A slogan on one of my early cards was, “Wear Your Dreams.” I was the first guy to say, “Bring me your idea, and we'll make a tattoo out of it.” It expanded the possibilities of the medium, and it expanded my repertoire; it challenged me as an illustrator. People bring an idea and you make it fit for them.

Were you still drawing and painting?

I always kept doing artwork for myself. But the next big thing was when I decided to move to Hawaii to start surfing again. I had enough of a solid business here, so we decided to just go off the deep end. I realized I had consecutive periods of time where I could just draw and paint. That was a big challenge, then, because I had become dependent on people coming in and giving me ideas. At first, I didn't want to make anything that looked remotely like a tattoo. But after a while, I realized that was just a conceit, because tattoo imagery is as much of my visual language as anything. So I got back to my own art and painting, as well as connecting to the great print masters. Then we started publishing books, one of them being the first real tattoo title. I was always interested in trying to broaden people's awareness and appreciation on what it was all about.

What I want to know about is my favorite image in your documentary Tattoo the World. I love the baked potato with the melted butter. It looks warm and wafting.

I particularly remember that one, got it from a little illustration in a '50s cookbook. It was up on a woman's shoulder, and she was one of those people, maybe she was in primal scream therapy, but I started tattooing her, and she's all yelping and ouching. I go, “You didn't know this was going to hurt? I know tattoos hurt a little bit, cowboy up, let's get the fucking tattoo done!” I always remember that. I loved that one, but I never saw her again.