Shepard Fairey

Punk and Progress

Interview by Gwynned Vitello // Portrait by David Broach

The musician who only wants to discuss his upcoming album, the film actress focused on her Broadway play, the painter who doesn’t acknowledge commerce. As I approached the Los Angeles studio of Shepard Fairey, I wondered who would be at the door, and if I’d zero in on art or politics, if Shepard Fairey would be tired of talking about Barack and Andre. His core team greeted me, none more enthusiastically than wife and partner Amanda, who eagerly told me about their upcoming show, Damaged (and a newspaper!) as I was ushered around a colorful pastiche of activity and movement, collage, prints and news clippings, as the new pieces gazed gloriously around the room. Shepard Fairey doesn’t put on his art or political hat. It’s all fair game because, to him, it’s not a game. In regards to parenting daughters Vivienne and Madeline, he stresses that “satisfaction in life is not just passing time.” For him, truth, indeed is beauty.

Gwynned Vitello: I have the impression that you have mixed feelings about your birthplace of Charleston, South Carolina.

Shepard Fairey: Well, it was very conservative. Not the whole city, per se, but the environment where I grew up. My mom was a head cheerleader who later became an English teacher and and my dad, captain of the football team, went on to medical school. I went to a private prep school, the same one, interestingly, Steven Colbert attended, where you had to wear a coat and tie starting in 7th grade. It was very strict, academically, and socially conservative. Reading Catcher in the Rye was very helpful, but until I started skateboarding and listening to punk music, I didn’t understand why I was so miserable. I did a year of boarding school, but put in as little as effort as possible, just enough not to fail out, and then finally my parents said, okay, what would make you happy? I went to public school for two years, but they thought I was hanging out with juvenile delinquents, which I was loving. There was diversity, there were people from different ethnicities, different economic backgrounds, and I felt like I could make own way on my own terms. At private school, if you were not a jock who wore polo shirts every day, then you were an outcast.

I didn’t mind being an outcast, but there was no one to connect with, no partners in crime. When I went to public school and had my skateboarder friends who were into punk rock and things I was into, that was good. But I think having to fight for the things I was interested in made me more committed and it made me soak up things up in a way that went a little deeper.

That would definitely contribute to your drive, but somewhere you learned the discipline and a work ethic.

We were definitely not rich, but I guess you could say upper middle class. My parents were very frugal, but also very shrewd, business-wise. My parents are very disciplined, and they did teach me, as much as I rebelled, that you don’t let people down by not delivering on your word.

So you can’t really take the boy out of Charleston, or Charleston out of the boy.

That’s another aspect that I feel is important, and that is to be polite and respectful when you encounter people casually, first impressions and all that. If you need to take a stand and be abrasive, wait until it counts and is absolutely necessary. Always give people the benefit of the doubt, treat them well and make sure that you’re respectful in your basic demeanor. So what I tried to do with Charleston is take the things I thought were good ideas and abandon the ones that weren’t.

Then it did provide a good foundation in many productive ways.

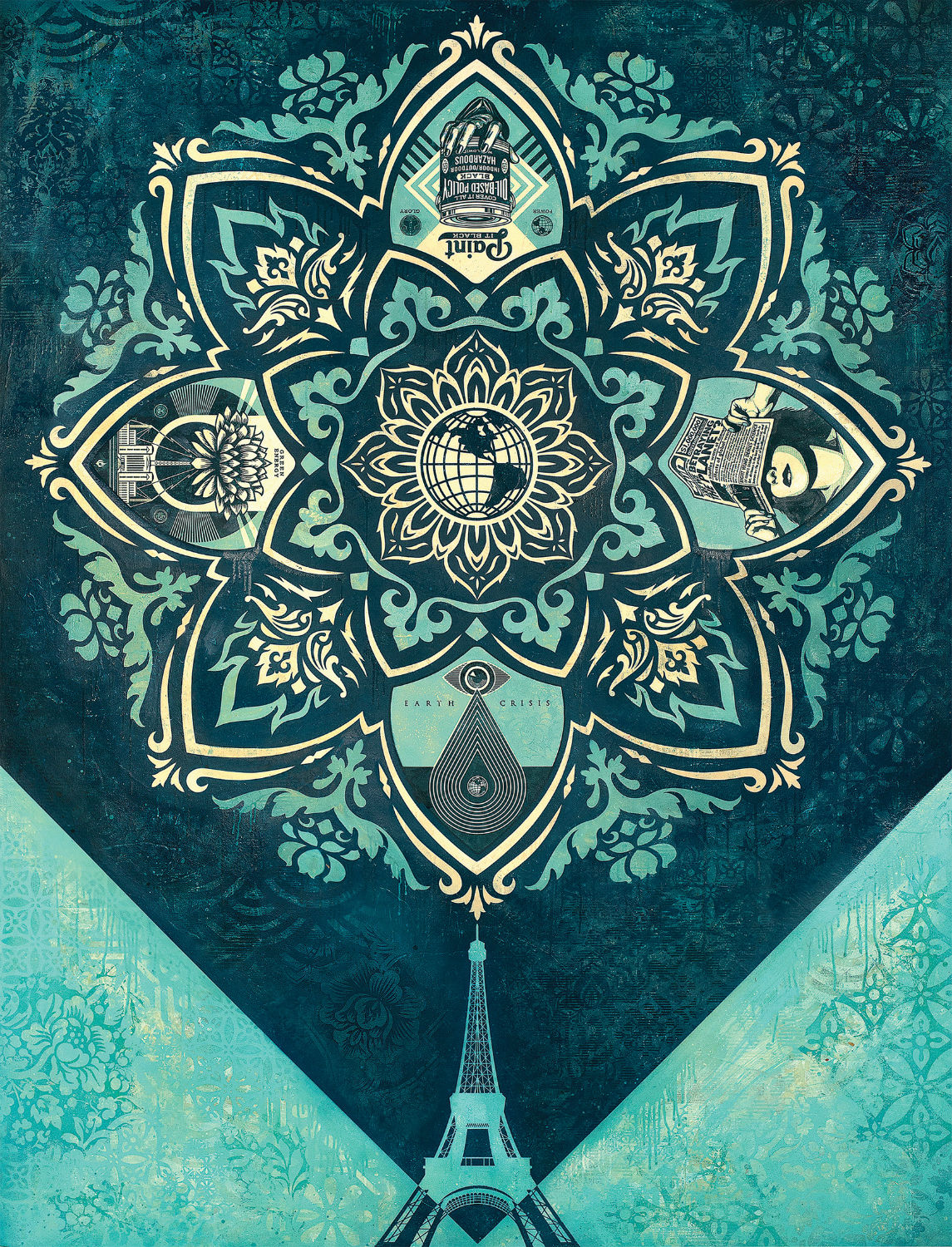

Another good thing about Charleston is that it is really a beautiful place, so I got a good appreciation of the environment: the beaches, the health of the ecosystem. When you are in a place like that, you need to have your eyes open, be impacted by it. My dad was a real outdoorsman, and took me out to identify birds and plants and things like that. I love skateboarding and being on the streets, but there is a side of me that really appreciates the beauty and vulnerability of nature.

What bridged those experiences with RISD, and what did you take from that art school experience?

Early on, it came from enjoying the process of drawing and painting, even if the subject was something I wasn’t passionate about. I did a lot of things that were still-lifes that I set up in my room, and architecture from around Charleston. I never really considered what would make good art other than technique, so subject matter wasn’t even something I thought about much. It wasn’t until I was about 14 and got into skating that I saw the connection with board graphics, with what Jamie Reid did for the Sex Pistols and Raymond Pettibon for Black Flag. Another thing that made me want to draw well was when I went to the Whitney and saw the Chuck Close portrait of Philip Glass. I was so blown away that I looked at that one piece for about an hour. I was just so moved by the meticulous translation of a photographic image to a canvas.

I wanted to draw photo-realistically and actually got good at drawing in that style, rendering with great shading and everything. Once I got to art school and became more familiar with artists like Close and Robert Longo, I felt like, okay, there are people who are doing this really well, so if I try and do that, it will look like a grade B version of what they do. So I had to figure out my vision, my choice of subject, technique, and concept that all determined the impact of a finished product, and each of these elements dictates whether you’re going to have a powerful piece.

That seems like a pretty mature understanding to have at a young age.

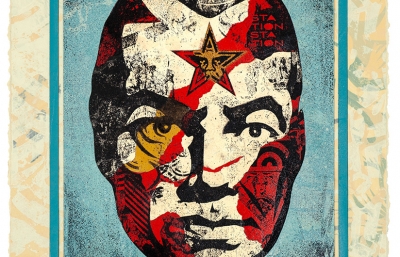

RISD is hardcore. When you go through that foundation, you have to learn how to explain what you are doing. It was a brutal critique to hear professors say, “Okay, this is well-rendered, but it looks like so-and-so,” and ask what new thing you are trying to bring to the equation. I learned by imitating so many different things. Most people are quick to point out the Russian Constructivism influence in my work; it’s more than me just liking it, but also that Americans have been conditioned to fear that aesthetic while at the same time conditioned to embrace American propaganda, which is advertising. I had something benevolent in a sinister package in what I was doing, and it was intentionally a pastiche.

Well, the advertising scenarios dreamed up by the Mad Men crew are pretty seductive.

Marshall McLuhan was an influence, but there was also this movie Putney Swope, really an outlier of its time. In this boardroom scene, the head of the agency goes, “First we stimulate the consumer by arousing their desires, and then we satisfy those desires for a fixed price!” Everyone is like a deer in the headlights, and it’s called advertising!

You were listening and you paid attention. Actually, you don’t look like someone who takes much time to relax.

Well, now I DJ, but I really relax when I am working on my art at home, working on a poster composition on my laptop.

That’s when I am most at peace. When I say I relax when DJing, that is when I feel light and happy about doing something where I get to be part of the musical and social energy without necessarily being kind of under a microscope. Whenever we do art shows, I DJ for a couple hours; some things are more hip hop or dance oriented, some punk. I like a lot of types of music.

Andre kind of started with you making T-shirts for your favorite bands.

Everyone thinks it was a school project because of a couple of things: I wrote what I now call the manifesto, but at the time, I called it a social and psychological explanation for how Andre has a posse, and I wrote it for a class. The original paper, which I lost, was six pages, typed. But I also did a one-page, abbreviated, hipster, short-attention-span version in 1990 that is still on my website. It describes the phenomenology of allowing things to manifest themselves, about reawakening a sense of wonder about the environment. I go through these things, and I noticed how it was working like a Rorschach test, how it was interpreted, and also that hipster club thing, that is... I don’t know what it is, but I know it’s perpetuated by something and I want in—I want to learn the secret handshake.

I wrote this piece for class, actually an architecture class, about how the psychology of spaces, their fixtures and details, anything having to do with these, are taken-for-granted interactions people have with faces. So my interpretation was that people take for granted their interaction with public space, public signage and advertising. When something else is thrown into the mix, it is perplexing, if there is no obvious reason for it to be there. The same semester, I had an illustration class where the assignment was to illustrate a fortune cookie insert, and mine read, “To affect the quality of life is no small achievement.” At the time, this ex-con, Buddy Cianci, was running for mayor of Providence and he had this billboard that said, “Cianci Never Stopped Caring.” It made me really mad because it did not mean anything, so I thought changing the billboard would be a pretty dramatic intervention that will affect the quality of the day for a lot of people. While I was looking at newspapers, I saw an ad for Andre the Giant, so why not? I had been making stencils to make T-shirts for the bands I liked, so up goes a pasted graphic of Andre’s face over Cianci’s billboard!

Now that I’ve got the story of Andre’s posse, how did Obey emerge?

Now that all my friends were asking, “Hey, can I get some Andre stickers?” I’m thinking about how absurd but amusing this is. I thought I should transition this into something meaningful because, even though it started off as a really stupid subject, it actually had some profound implications. I drew from a foundation in literature, Ray Bradbury, for example, but John Carpenter’s They Live was a big inspiration. Remember when Rowdy puts on those glasses and there are commands like Consume, Watch Television, Reproduce and OBEY. The idea of making people have to confront obedience seemed really powerful, and that is why I went with that word, sort of Russian Constructive stuff, sort of Barbara Kruger, who went beyond just being an artist you might be inspired by. She was so influential, her very style seemed to say, “This is art with political intent.”

As political intent unfolded in your art, what annoyed, angered you?

This was during the Clinton era, and I wasn’t mad about specific things, policy-wise. I was more irritated by things that annoy every petulant teenager—parking tickets being expensive relative to the scale of the crime and police harassment of skateboarders. But other matters started to creep into what I was portraying in my work, like corporations abusing power and capitalism becoming the new religion. That was big for me.

And then came the Obama poster.

I was saying, hey, Obama is awesome, check him out and support him. With the Hope poster, I was saying, “Here is why I think Obama is the best choice for president.” But also that there are all sorts of ways to look up his policy positions, read his speeches, watch his videos, and make up your own mind. To those who would criticize this by calling it propaganda, I would say that it is not. Propaganda would be the last word in a conversation, and I am urging this to be the start of a conversation, maybe this is an option you haven’t thought of. This is what a lot of my work is about. When greed and indifference is that status quo, it’s time for conversation.

I went to the Women’s March in D.C. and it was upbeat, full of hope, and the desire to move forward, which was very energizing. But look at where we are now. What next?

Our system of democracy, I think, alienates some people, yet it is the system we have and the only way to change it is through the system itself. You have to participate, but so many people don’t want to come to terms with that reality—that they would have to interface with a flawed system would seem like a compromise to them. Or maybe they say that to justify their complacency.

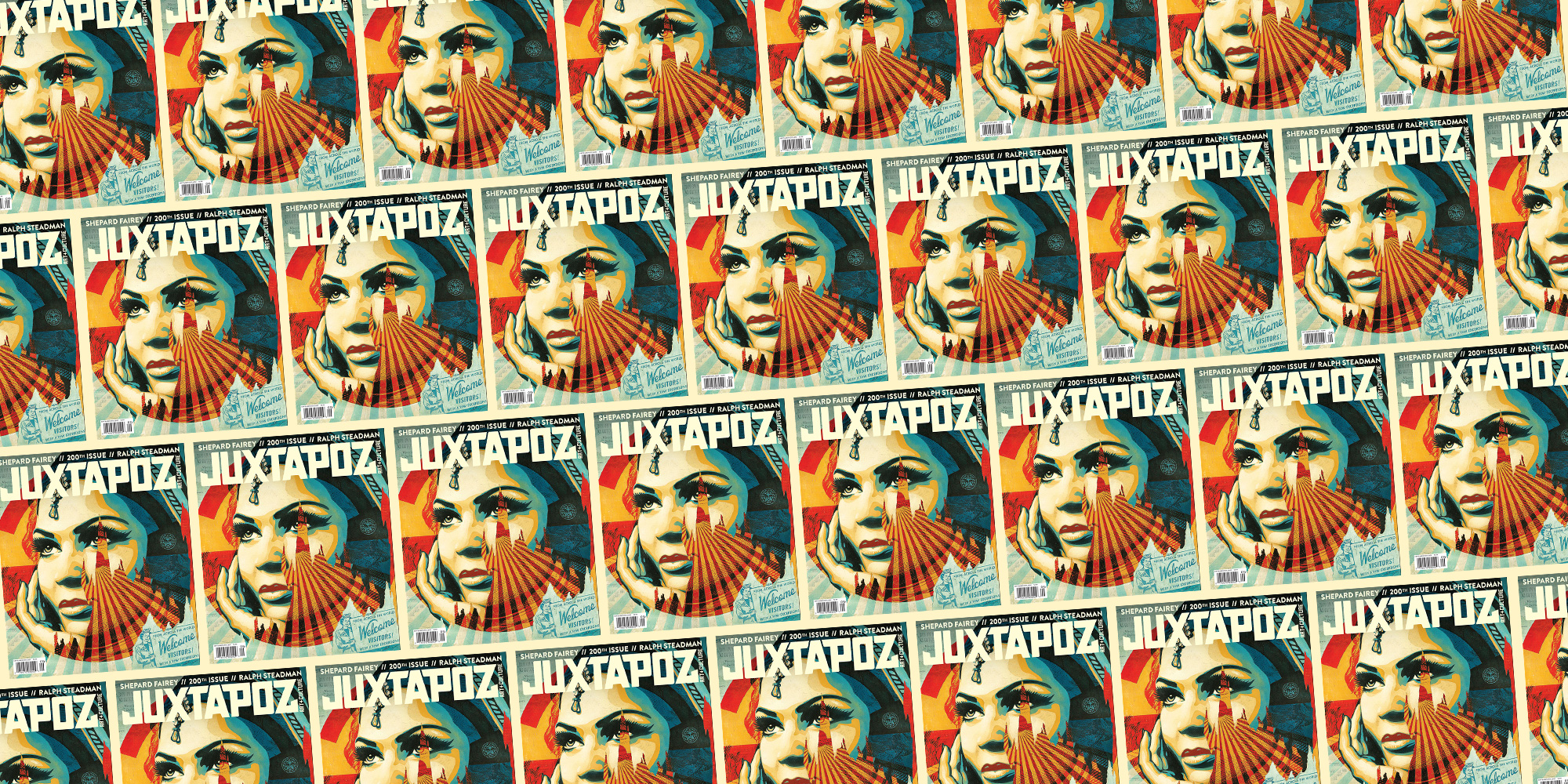

You saw the images that I worked on for the Women’s March. Those were a commentary about a situation where everything seems to be about division and no one wants to listen to the other side about how we define universal, unimpeachable human values. I mean, if you have a problem with theses ideas, you really are outed as a bigot. So it’s a little like, hey, kill them with kindness and give them enough rope.

Aaron Huey, who worked with me on the images, he and I both felt like a lot of people are under fire from Trump, but probably the most vitriol is directed towards African Americans, Latinos, and Muslims. We decided to make images of people from those groups, making sure they reflect the idea that, at one point, we were proud the US was a melting pot for people to escape to from being persecuted for their religion. That is the American Dream, you come here to work hard and get ahead... equality. A lot of the images from my new series are intentionally attractive, not looking like models, but attractive in that you relate to their humanity. And when someone radiates, at that first read is an undeniable humanity, then you see other layers, and maybe prejudice can be stripped away if there is some compassion. Sometimes, in the same piece, I’ll put in different bits of text, maybe about Islamophobic rhetoric as well as stats about how their crime rate is lower than other groups. I wish that every image could resonate like the Hope poster, so I am always trying to make work I think is touching on things that are very relevant. Sometimes I make an image that comes back to life a few years later because something in the news cycle really relates.

Maybe I’m reaching, but is Andre kind of like your Greek Chorus? Things happen around him, he’s the everyman

Amazing you said that because I have said that sometimes he is the hero, and sometimes he is the villain in the way I am using him as an element. I call him the Obey icon, but the Andre face is the origin. I use that idea that something can come from very humble beginnings, very do-it-yourself.

Did your new show come about because it was a good time and there was a good space, or because you had some new ideas to show?

It was a combination of the two. I wanted to evolve some of the aesthetics of my work. I’ve used ripped paper and collage, but here I wanted to show them as symbolizing a fight between elements. We are culturally and politically in fight mode, and I wanted to encapsulate what is going on socially and politically, also using more color. I wanted to bring the best of what I do graphically for prints with a little bit more of an organic painterly style.

I also like duality, the idea that something can be seductive and provocative at the same time. So these new pieces are in your face, controversial, but you could say there is a bait-and-switch component like, “Oh shit, I really did not want to have to think about that, but now it’s too late.” People say that my activist work is so generous. I say, “No it’s not. I want to live in a better world—it’s selfish!”

I’m looking forward to your newspaper Damaged Times, what you call, “giving people a fresh perspective.” I love what you are doing to encourage engagement.

Even if it goes away, I am not going down without a fight. The only thing worse is not trying to do something about it.

Shepard Fairey’s exhibition with Library Street Collective in Los Angeles opens this November, 2017, and will coincide with the release of his Damaged Times newspaper.

obeygiant.com

END