Jesse Mockrin

A Tragedy in Two Parts

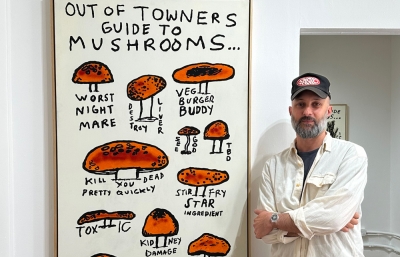

Interview by Shaquille Heath // Portrait by Max Knight

In one of Jesse Mockrin’s most recent works, for she died, the artist reimagines Francesco Furini’s 1632 painting, The Birth of Benjamin and the Death of Rachel. It was shared that Mockrin was first intrigued by this biblical scene by a small gesture that could have been overlooked by the sharpest of eagle eyes: a figure sewing up the fabric of a woman’s dress, happening just moments before her death.

Mockrin, who could easily take on the role of a historian or archivist, learned that this gesture may have been an allusion to a caesarian section procedure, particularly by the presence of a man whose appearance indicates that something has gone wrong. With our own current issues—or rather the eternal battle over the autonomy of women and pregnant bodies, the forceful intervention of men, and the politics of belief, morality, and justice—this painting struck a chord, resulting in Mockrin’s staggering rendition that caught many an eye at Art Basel Miami this past year.

That’s a little peek into the process of Mockrin’s divine oil paintings. Based in Los Angeles, her works appear to come from a land much, much farther away. Looking to iconic paintings from the Renaissance and Baroque periods, she zooms in, crops out, and fixates on a central element that has been lost in all the theatrics and drama. Her canvases illuminate these in our contemporary moment, directing attention to the conversations that we should have been having all along. These works tackle the most burning of subjects—gender, power, violence, and sexuality—the yummiest of aperitifs for dinner party conversations. And why, again and again, these matters emerge when we think we’ve put them to bed. Ultimately, at the heart of it all, I believe her art often asks quite a simple question: Who gets to live, and who has to die, for the choices and consequences of men?

If history is a tragedy in two parts, Mockrin makes these points: First, that tragedies happen. Second, that we let them happen again.

Shaquille Heath: So I have to ask the dreaded year-in-review question. We're at the end of 2022 as we speak now. I'd love to hear how it feels looking back.

Jesse Mockrin: It's crazy how compressed everything feels now. I feel like there were two years just in the past year. I was actually just looking back to pick paintings for this feature, and I was like, “I did all this in one year?!” It just feels kind of like a time warp. I had my fourth solo show at Night Gallery in May, so that was really exciting. I've worked with them for a long time now. There were new moves in those paintings that I was excited about. I also just signed on with James Cohan Gallery and had my first painting in Art Basel with them. It's an exciting new relationship in New York. So yeah, it's been good. And then for the most part I’ve been able to keep my children in school consistently. So that has been nice… yeah, that's what comes to mind off the top of my head. At least what I can remember because the rest is a blur.

I totally hear you. When I think that we’ll be hitting the three-year pandemic anniversary… that doesn't feel right. That's so exciting that you had your first piece at Basel. I honestly can’t believe that! But also, you're a mama? How many kids do you have?

I have two boys. They are almost six and eight. I basically was pregnant with my first child at my first solo show. So, the career that I've had, and the children, have all come at the exact same time. I’ve always had them together. And it's, you know, so fun to juggle them…

Have you seen a change between how you approached your art before you became a mother and after?

I'm sure it's affected the things that I think are interesting. For example, it wasn't until I had kids that I started thinking the Madonna and Child images were interesting. I'm not particularly religious, but I thought, Oh, this is just a mom and a child! This is the most fundamental thing there is. So things like that I could relate to differently.

I've also started to see my work through my children's eyes, which is interesting. There tends to be a lot of violence in the work. And so sometimes I've had the kids in the studio, and they're like, “I don't want to look at that!” I’m like, “Oh my God! Your mom's so weird!” So it's made me reflect on that, and how I explain it to them. I'll tell them, “These are based on old stories.”

But anyway, it's a very selfish thing making art, but it's made me realize a little bit more that there is an impact on the other people around me, and my life. In more ways than one. I did this show in 2019 at Nathalie Karg Gallery in New York, which was all based on Lucretia. In that story, she's committing suicide with a dagger. I had these paintings everywhere and my son was just like, “Where can I sit where I don't have to look at these?!”

That's actually quite funny! I’m sure one day he'll view them with very different eyes.

Yeah, exactly! I mean, that's kind of what the work is about, to some degree. It's about how with time and the changing of society around you, the work appears different. It's interesting to see how different he sees it from me, with all of the art history I've been exposed to over time, and my understanding of the art world. And how, to somebody with such a limited experience, they're just like, “This is really creepy!”

Well, actually, that’s a perfect pivot because I always love to hear an artist explain work in their own words. May I ask that of you?

I focus a lot on reframing works from European art history, usually cropping details, and then re-presenting them in a new context. I'm mostly focused on issues around gender, the body, violence, and sexuality. In the past, maybe four years or so, it's just been exclusively art history. Before that, I was also looking at contemporary popular culture. I had sort of a mix, but the work is always kind of about this time travel. Bringing things from the past to the current moment. Or putting the past and present into this confusing relationship, side by side. I think the aspect of appropriation is important to me, and how context will transform the meaning of these really, often repeated narratives.

That's the lens with which I'm sort of looking. The things that I'm drawn to over and over again tend to be about gender and the body. I started painting in high school and I’ve always been really focused on the figure. I had a really great painting teacher in high school and he would take us out and do plein air painting. I would always put figures in the works because I didn't really know how to make a painting without a body in it. It felt like that was what activated it. And then in college too, the work I was making was about gender and identity. I went to Barnard, it's an all-women's college, so it's funny how the work can change. Like, the work in grad school is different, but these core ideas are always present.

Where do your ideas come from? Are you visiting museums? Mostly looking through books? Inspired by something you saw in White Lotus?

I loved that show for that reason! I was like, “Oh, that's St. Sebastian! That's St. Agatha! It was very fun for me.

We just finished the last episode and I’ve been making a lot of connections with your work as I was preparing for this interview.

There are a lot of paintings of the saints. And the martyrdoms of the saints—they're so messed up, and so gory! I do all of the above. I go to museums, I look at books, I go to libraries. The more new ways I can access images, the better. If I'm going to a new town and am going to a totally different museum that I've never been to before, that’s really exciting. I've tried to hit all the University art libraries in LA. I'm from Maryland, so when I've gone home, I go to American University’s library.

I usually have a couple of things to start with, and then I'll see other things in the process. I have this collection of images that, so far anyway, have continued to inspire more and more work. And then once I have those images, I'll make small sketches from them. That's usually a small section of a painting, but sometimes it's a section that then is expanded, or a diptych where two different things are put up against each other. I'll make these sketches in my notebook and from there I can photocopy them, cut them out, and see how they relate to each other to sort of plan a show. I usually make a lot of drawings before I figure out what the next show will be, or what the next things I want to make are.

What’s your process for choosing subject matter? Is this also more visual or do the instincts come from the subject matter itself?

Yeah, it feels like a weird sort of cycling around. Often I'll start off with an idea. Like I made this show that was all about St. Sebastian for Night Gallery in May. And that one I started by looking at Dutch still life. I made a few select paintings and I thought, well, what if I did a whole show? So I got all these Dutch books. And in one of them, I saw this painting of St. Sebastian, and then I got kind of obsessed with that. So it's kind of this meandering path.

But, maybe that still life show will happen later? There are ideas that I put to the side that maybe I will come back to. There are just things that are sort of simmering back there. For example, I did a show in 2018 at Night Gallery and some of the imagery for that one was based on witches. I'm still pretty into the witches. So whenever I see anything, I'll collect it. If I come across a book that deals with them, I'll get it. I’m starting to amass that stuff. I don't really know the next step until the one before it has been laid out. It’s kind of unfolding a little at a time.

Do you find yourself gravitating towards certain iconography or postures?

I like Baroque drama. There are a lot of theatrical dancer expressions or physicality in the bodies. With reference material that I like to work from, it tends to be painters like Bronzino or Rubin's—where the emphasis on line was very clear, as opposed to somebody like Titian or Delacroix where it's really color based and textured. I am drawn to the more linear figuration.

I always get excited when there's a female painter that I'm looking at. I’ve looked at a lot of Artemisia Gentileschi. It’s always interesting to me to think about what it must have been like to be painting at that time as a woman.

I'm always drawn to hands. They are a recurring symbol in my work. I think that one of the things that I'm always looking for are the gestures in the paintings and these kinds of active hands, even if the gestures aren't a language that we necessarily have the key to anymore. There's still something about the way the hands are the actors in the paintings that I think is really interesting, and that I am interested in within my own work.

The hands! There's just this really fun and interesting fluidity to the way that you paint them. This boneless state. It almost gives this layer of freedom, almost as if they're not even attached to a body. For example, if we are thinking about them in the context of the body, it feels like they're the brains—they're the ones who are making decisions.

I love that! I love the kind of mannerist fingers and that way of drawing them. I used to grid things in graduate school and draw really realistically. When I stopped doing that, that was one of the things that first started to emerge in the work, were these curly fingers. I think it's because a lot of my interest is around this idealization in the grotesque. And how this idea of the elegance of the gesture becomes grotesque when it's exaggerated to a certain degree. So I feel like they look elegant. But if you think about the physicality of those hands, then it becomes really bizarre. Like, how can you grasp something with those hands? To be so elegant to the point of losing function is a really disturbing idea. I think that's where my interest in them comes from.

I like what you said about them being like the brain—I think that's great. I often have thought of them as a stand-in for the whole body. You know, maybe if you just had a shoulder, that's not enough to communicate a story. But if you have one hand, it can hold enough meaning for the whole painting. I love that idea… and then they're also kind of like tentacles or animals.

They really do feel like they have a life of their own. I love that there is an intention on your part for grotesqueness. And I agree that the mannerisms of our hands can play this whole part.

Yeah, absolutely. I think of the edges of the frame as sort of truncating the body. So you can have almost what feels like this disembodied arm or hand that you don't know where it's coming from. I usually think of it like a stage or a black box, so these things are reaching in from the outside of the frame. But it is sort of… the body, as disembodied. As an object. And I'm looking at all of this violent subject matter and I think of that as being the psychological effects of this violence. That's the impact it has.

I know gender is such an important part of your work, and I’ve read that it's very intentional on your behalf for gender to show up in your paintings as very ambiguous. I also watched a talk you did where you discussed your unisex name and its possible influence on your interests.

I do think my name probably played a role in how I think about gender. But also, my parents grew up during the Civil Rights era. There are all these photos of us with them at Equal Rights Amendment marches and stuff. So they always… my mom especially, was like, “You have these unisex names so that you won't be discriminated against based on your gender,” as if that could solve everything. I guess it was just one piece of the puzzle, but I kind of latched on to that, I really like it. My sister doesn't use her unisex nickname anymore, she just prefers Miranda to Randy. But I've always identified a lot with Jessie and not Jessica. It gave me this lens to think about, “Well, how would the world be different if I were male?” So just going into it, questioning that and all the constructs around it, and then going to an all-women's college… I mean, it's fertile ground!

I think getting beyond the male-female binary is exciting to me. This idea of breaking down gender roles and realizing how much more fluid and individual everything is. And so, in my work, there are these bodies that are not determinate, and they don't have biological signs of gender to go on. And then the way that leads to different interpretations is interesting to me. Allowing for something outside of the hetero-male gaze that we were taught was the norm in European art history.

And then also, you know, reclaiming art history from a feminist perspective is interesting to me, looking at a lot of stories about these female characters, and what's happened to them, and why that's relevant now.

What does history mean to you after doing all of this research and seeing how things are so cyclical? How has its meaning changed as you've continued to do more and more work?

I think it shows me how some of the assumptions that people tend to make about the past… it brings them into sharper relief. I feel like we tend to think we invented sex and perversity, and that people back then were really prudish and not creative. That's not true at all. Meanwhile, as violent as things are here, at this moment in time, and how much of this violence repeats itself, I think we still are at the least violent time in history. So it's both encouraging and sort of depressing to look back. But it's interesting just to realize, these were people just like we are. They feel almost like a different species sometimes. It’s exciting to work with the material and to feel this kind of human connection. And yeah, to see the things that continue and continue, like the fight to control women's bodies. I mean, that is never-ending, apparently.

One of the works that was at Basel was for she died. I read that this was a piece that you reimagined from Francesco Furini’s 1632 painting, The Birth of Benjamin and the Death of Rachel—a work that's about a biblical birth. I was really stunned and moved by your focus and prioritization of the mother, in the midst of a devastating C-section. Although your focus isn’t pop culture, again we’re seeing this representation in the new Game of Thrones series.

I mean, that's the thing, is that a lot of times, there'll be stories that were painted over and over, but the female characters in them aren't thought about. They aren't given their own sort of priority or psychological importance. They're a result of something that's important, or they lead to something else that's “more” important. But they're just not focused on. A lot of what I'm doing is just trying to refocus the narrative around this female character in her own experience.

That's a painting that I came across, but I thought, I don't think I've seen any other paintings that depict birth. And given the political moment that we're in, it really resonated with me. I was looking at a lot of images this past Summer and feeling very angry, and it felt really moving to see that and then to learn more about the story and realize… it's complicated. Like she desperately wanted to be a mom and it's a tragedy that she lost her life in this way. But what I think is so crazy-making is that the struggles that women go through to have babies, or to avoid having babies, and that that is still something that women aren't being allowed to be in charge of even when we have all the medical information and power that we have today. So that's what making that painting now felt like to me. That they're really people who want us to go back to this time. And it's just crazy.

Jesse Mockrin’s work can be explored in a new catalog Reliquary, by Night Gallery // This interview was originally published in our Spring 2023 Quarterly.