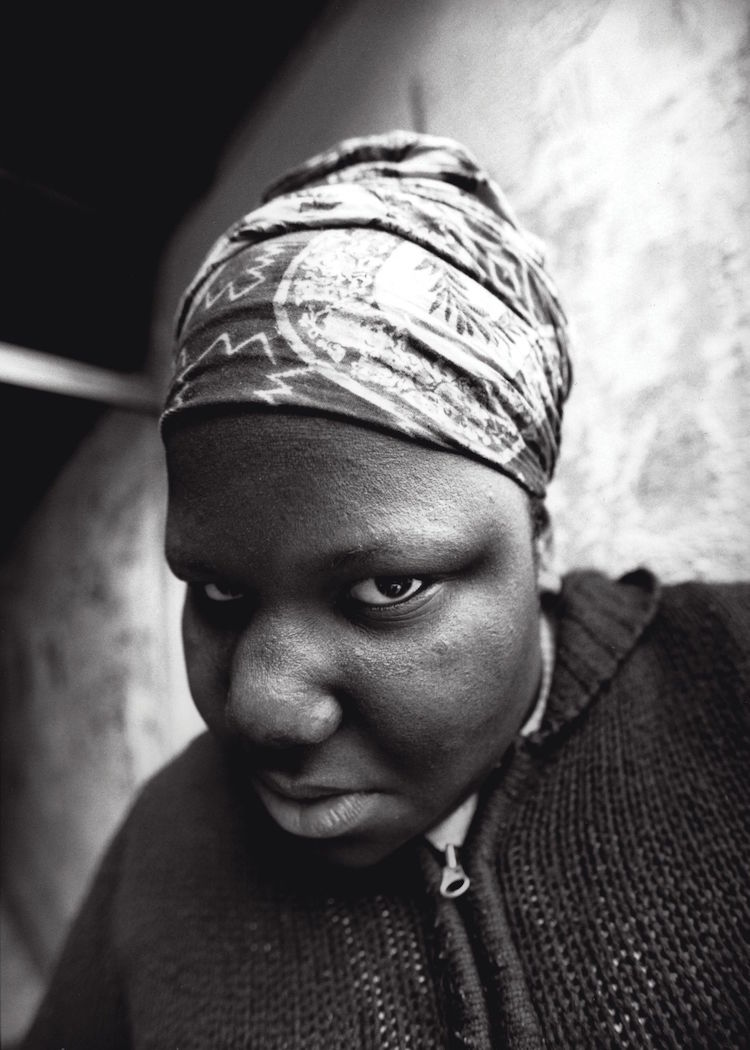

Knowing that he sued you?

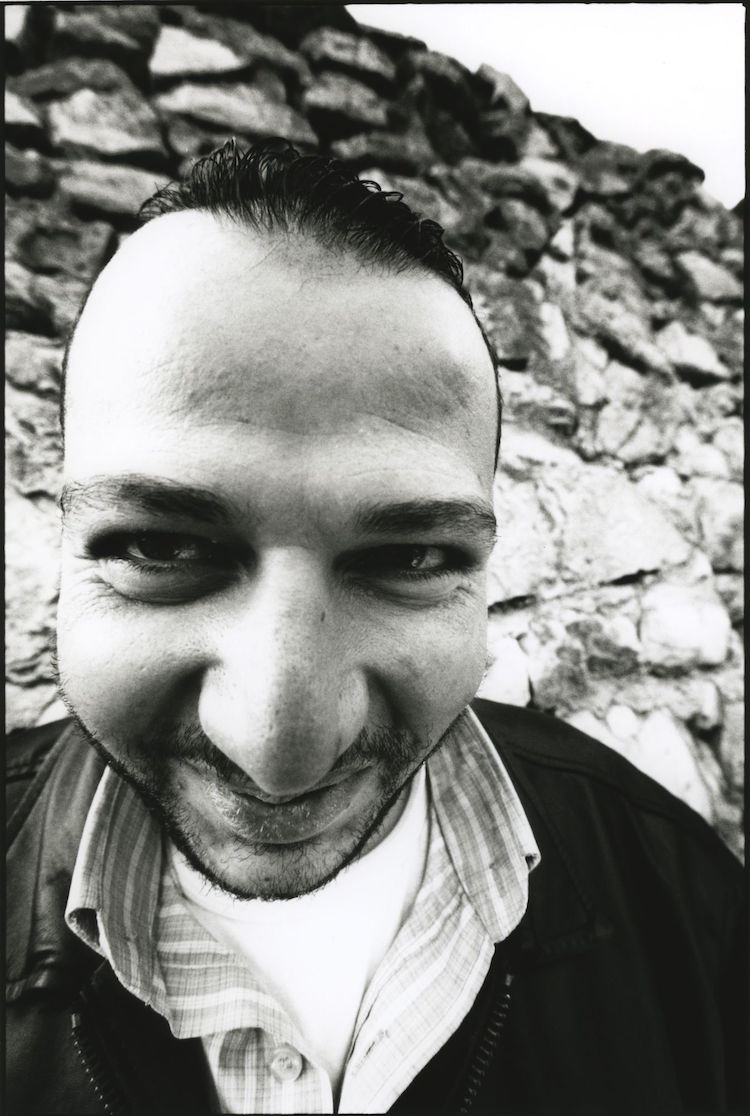

Knowing he sued me and we'd be enemies, and you have no idea. Over the years we have done documentaries, films where you see him say, “Well, I sued because they never asked for any permits.” We're big enemies for all those years. When he came to be photographed, we said, “This is what's going to happen; everyone can be represented how they want.” He brought his sort of political sash and said, “I want to be as the mayor." What we told him was that some people would pose and turn their back on him. He said yes and played the game.

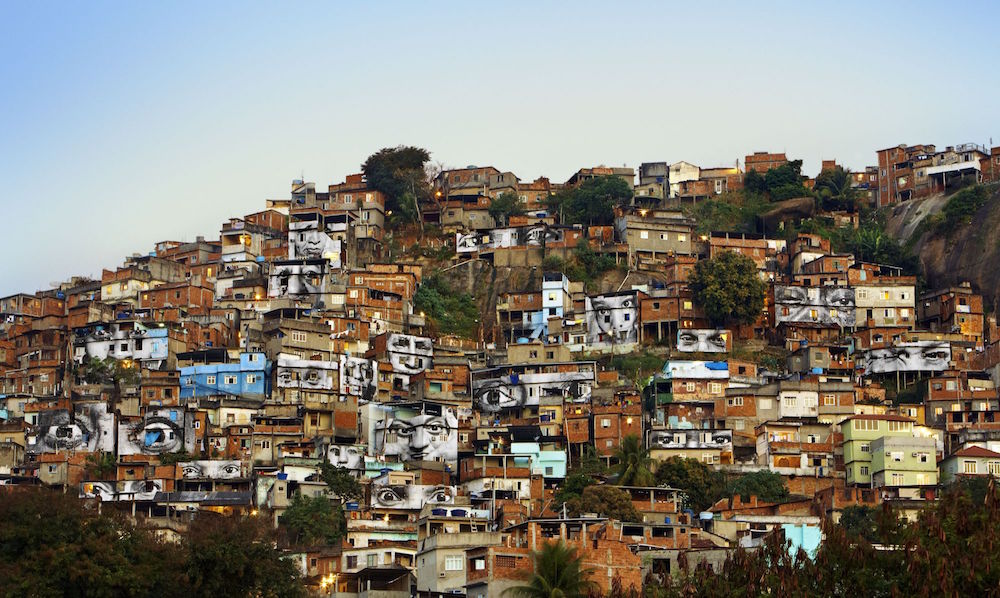

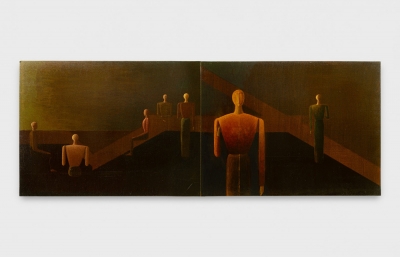

When we finished the whole project, the mural was shown at the

Palais de Tokyo in Paris. We had an opening, and all the people from the neighborhood were invited. Amazingly, the President of France at the time,

François Hollande, heard about it and asked to come! He came, but early, like at 3PM. We meet him and he goes, "Oh, my god!" He looked at us, then at the mural, and said, "That's the history of France, you know that?" And we're like, "Yeah, we know." And he started naming off some of the people in the mural. Because all those people were in the media at the time, you have to understand that. This was the epicenter, like it exploded in a way that France has never seen it.

So the president says, “Where are the people?” I'm like, “Well, your security asked that you be here at 3PM, so there is nobody. They all come tonight, at the opening.” He says, “Well, no, no, I should be meeting the people. That's very important.” And he said, “I'm canceling everything today. I'm staying here until they come.” So we stayed the whole afternoon with the president, just chilling. Like sitting in cars, going around the museum. Waiting for the people. The people were all late because the buses were supposed to arrive at six. Of course, everyone is late for any reason. They get there at seven.

When everybody came and saw how big the mural was, everyone wanted to find themselves in it. So they barely saw the President. But he was into it, too. He was asking people where they were, got their stories. So it's interesting that all this, and the dialogue that comes in, again, activated some positive things in the neighborhood.