Jules De Balincourt

Searching the Wave of Possibility

Interview by Marcel Dzama // Portrait by Bryan Derballa

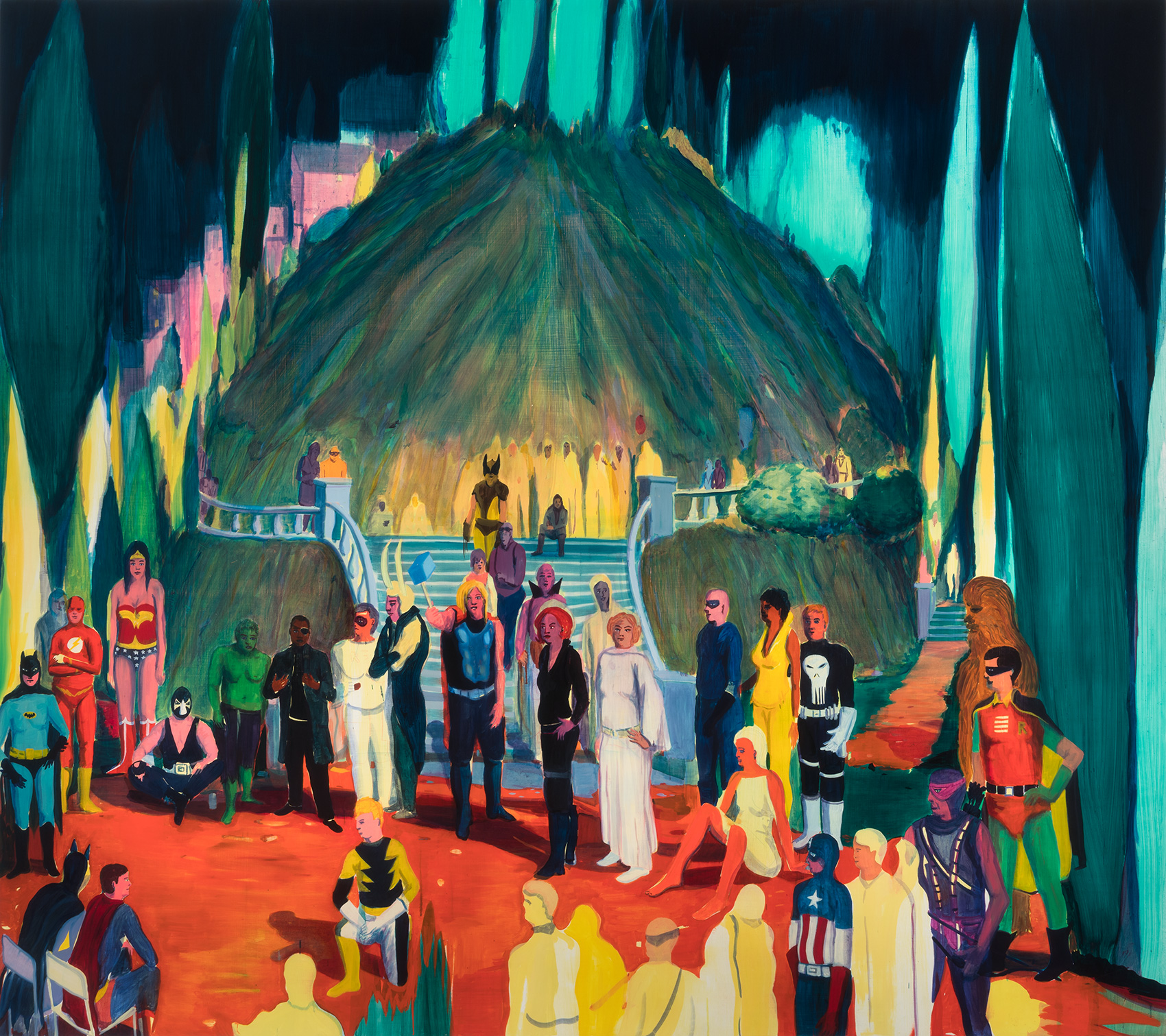

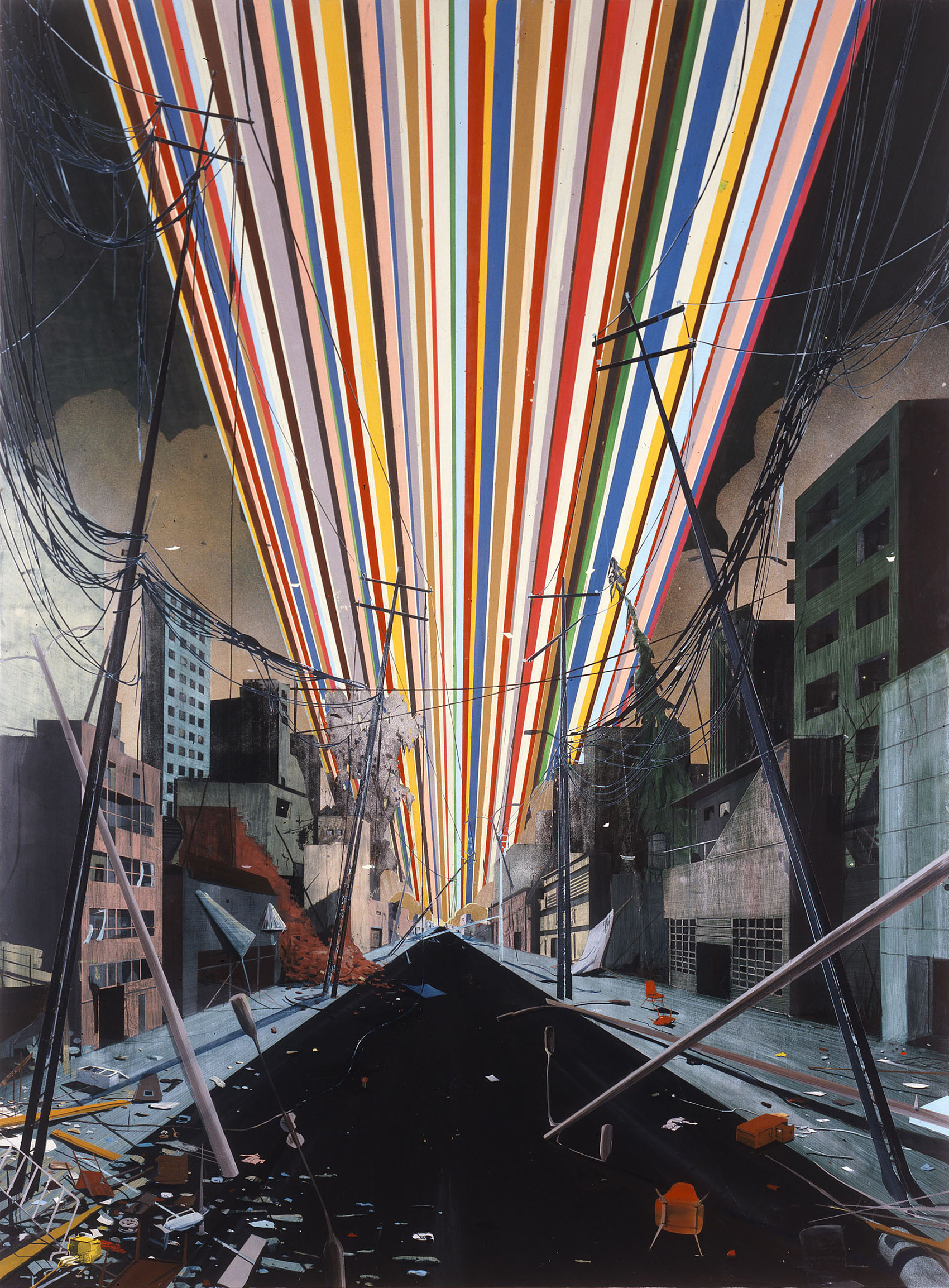

There’s the depth and scope, the sensational fields of vision in the paintings of Jules de Balincourt. As if in perennial perch just above the action, or off to the side observing the group, de Balincourt has found a unique angle in portraying our humanity, bordering at times on abstraction and even mysticism without straying too far from our reality. The colors may seem overly vibrant, the scenes a bit surreal, almost dystopian, but there is a familiarity and dreamlike paradise in each painting. From the hallowed galleries like Victoria Miro or to Girl skateboard decks, de Balincourt’s work speaks to multiple audiences even as he becomes a staple of the fine art world. Marcel Dzama, a contemporary and fellow New Yorker, sat down with de Balincourt to share their collective insights on artistic practice, the power of scale, and hearing the voice of Vincent Price.

Marcel Dzama: I’ve noticed that your work is getting a little more political lately. Not that you haven’t touched on politics in the past, but I see it since the election, and I like that. Did you imagine your work going in this direction? Do you approach a painting with an idea or more formally?

Jules de Balincourt: Yes, it’s difficult during these Trump times for there not to be some sort of dark reaction or tone that starts to permeate in the work. As you might remember in the early 2000s, when I first started showing in New York, my work slowly became reactionary to the Bush-Iraq era.

I never really saw myself as a political artist. I think I was simply hypersensitive and aware of the political climate, and as that saying goes, “If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention.” In these current times, if you aren’t against Trump or speaking against him, then you’re ultimately supporting him.

Regarding approach, my paintings begin in a purely abstract, intuitive place with no set preconceived image or idea. It literally begins as an intuitive dance of sorts, which eventually evolves into a recognizable figurative space, but is initially mined from a subconscious place. I’m interested in what happens in that crossroads where the work transforms from a purely abstract place and the decisions that are made to bring it into a figurative reality.

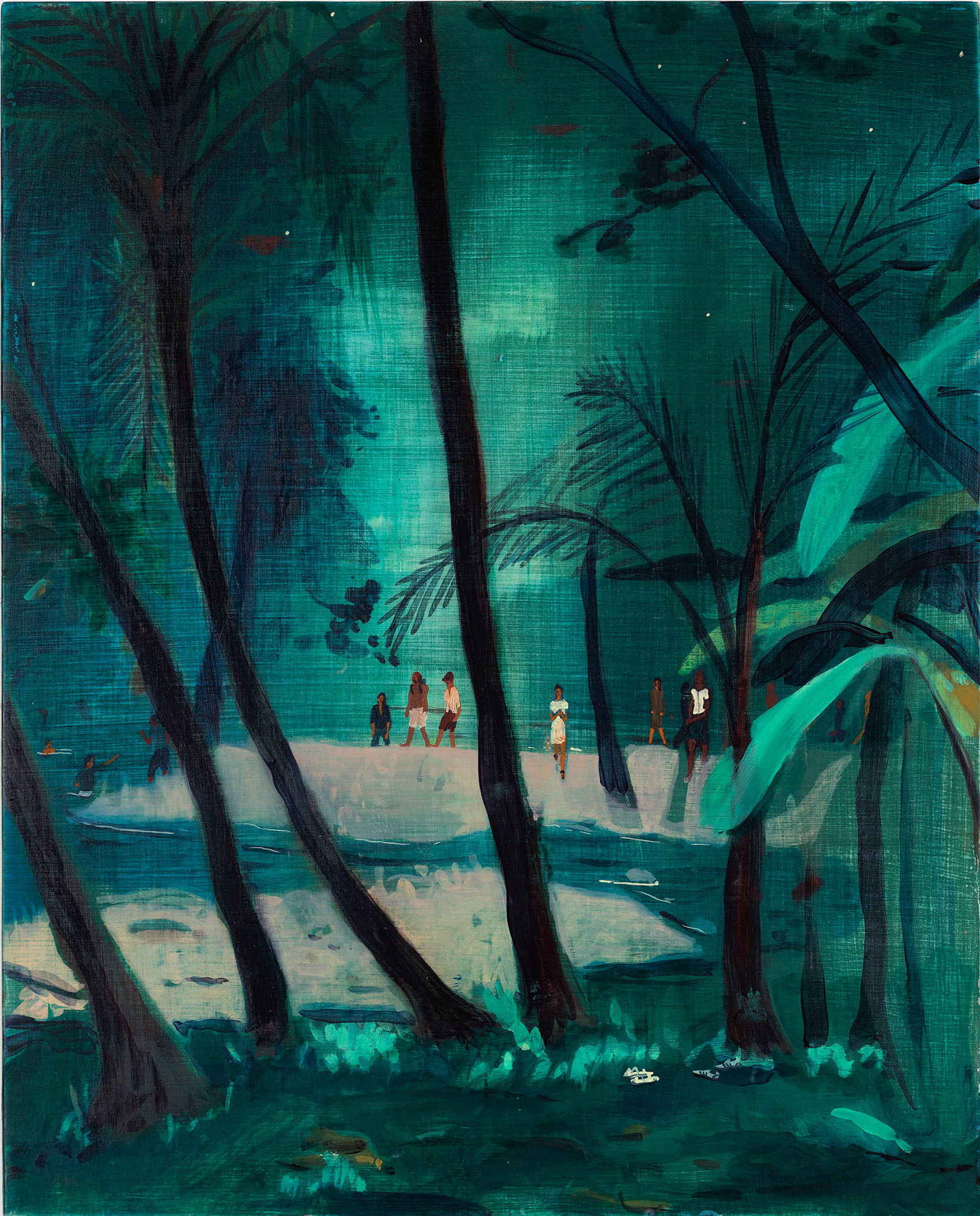

I’ve also always had a feeling of community from your work. These panels tend to be brightly colored and filled with people. You can sense the humanity. I notice it because my own work can skew negative, and I don’t always like that about myself. I like how hopeful your work feels. Do you paint those images from life? I know you are big into surfing in Costa Rica, so is that what I am seeing when you paint palm trees and people on the beach?

It’s funny, no matter how much I try to experiment or go into other directions, these little populations, or communities of people congregating always seem to reappear. After so many years of painting, I’ve given up the fight or the desire to change this about my work and am interested in these spaces and places that teeter between a utopian Eden and the post-apocalyptic.

I like the dark, almost witchy elements in your work, but I understand that desire to seek something we don’t necessarily intuitively do. I’m trying to imagine if your art was translated into music, what music would it be? Or if my work was translated into music, what would it sound like?

Maybe, for me, it could be a lost home recording of someone like Vincent Price performing a vocal track on top of Anton Karas’s haunting zither. What do you listen to while you work? Or do you listen at all?

My playlist can go from Bollywood music to West African pop, to Serge Gainsbourg, to some cool new band my studio assistants get me into, all within the span of an hour. It’s also similar to working on small and large paintings—there are moments when I want to listen to intimate, folky music, and other moments when I want to listen to West Coast rap. It covers a whole spectrum, but I never liked Jazz or Disco.

But back to your initial question, based off my work, I can see elements of my upbringing in France, Ibiza, Zurich, and California. Thinking of your work, I can’t help but associate a hermit in his cave during the brutally cold months of winter in Winnipeg, creating his own mythology.

Like the people that populate my paintings, another recurring theme is nature, landscape and the human relationship with nature. Yes, Costa Rica, and travel in general, has always been a source of inspiration in my life. I’ve been going to Costa Rica for over 20 years and I’m now in the process of building a house and studio there, which will also serve as an artists’ residency and retreat.This will be another sort of variation of Starr Space, but in the tropics. I don’t just want to paint utopia. This is my attempt at making one.

I love that you are able to create these communities and continue that in Costa Rica. I would love to go there with you one day. Can you explain what you were trying to do with Starr Space?

I ran Starr Space in Brooklyn from 2007 until 2010 in the space that is now my studio. It became an alternative community center, my own micro-mini-utopia. This was a space in which I was able to bring together the local community for events, including yoga classes, dance, cinema, and art, all under one roof.

Who are some of the artists that have inspired you, and has the list changed over time?

Oh, god. Well, the names are endless, so many great masters and underrecognized outsiders are there, too many to list, but as far as current political art, I love what you and Raymond [Pettibon] are doing now. I also like this new figurative painting coming from artists like Loie Hollowell and Shara Hughes, the political bite and punch of Kara Walker, the mystical, shamanic elements of Chris Ofili, and even newer discoveries, like the under-recognized Bob Thompson. As far as Old Masters, I’d have to say my top five are Goya, Manet, Velazquez and van Gogh. And then the American pre-war: Charles Burchfield, Milton Avery, and Arthur Dove. And of course, the mysterious Swedish Hilma af Klint, the first true mystical abstract painter.

I know you like to travel a lot and work in different places. How does location affect your work, and does it change a lot depending on where you are?

That’s a good question. I’m realizing it really does affect my work, and it’s something I want to explore more. I like the idea of not being so anchored down with one studio and being more mobile and nomadic. That’s what I loved when I came to visit your house and studio. It seemed like your studio could be a kitchen table with a light and some Bob Dylan in the background, without all the confines of a big space and all the materials that consume it. I’ve started working more in Costa Rica recently, and I love the immediacy and the different challenges presented by working in a new context.

Have you ever worked in mediums other than painting?

Yes. I didn’t actually study painting in school. I studied ceramics and also got my degree in it. I was always drawing in high school, but my first real exploration in art was through clay. Eventually, it became more and more about the paintings I would do on the ceramics and then, when I moved here from San Francisco, I abandoned working in clay because of the financial demands of running a ceramic studio in New York. But I have intentions of playing with it again. Painting is a job; it’s a job I love, but it is a job to me. And it would be nice to find another medium that presents a more playful outlet for exploration.

As a kid, how aware were you of the possibility of becoming an artist? Was your family aware of art, or was there one person who pointed you in that direction?

Luckily, from an early age on, I was exposed to art and my family’s community of artist friends. A lot of my parents’ friends were either artists, writers, or people working in cinema. I also had the good fortune of attending a Waldorf school in my few early formative years in which numbers and language were replaced by clay and crayons. Eventually, my parents realized it would be a good idea to also learn to read and write!

What was your childhood like and how did it inform your work? Does it still?

It definitely informs a lot of my work. I didn’t have a typical upbringing in the sense that my first four years of school were in different countries. By the time I was eight I had lived in, as I mentioned earlier, Paris, Ibiza, Zurich, and California. I moved to a new school every year, and let’s just say my mom was wonderfully wild and it was the 1970s. In many ways, my work reflects some of the chaotic travel and displacement I experienced as a kid. But, all in all, it was a good experience and it opened up my views on the world, exposing me to many different cultures and people at a young age.

How did you excel in high school? What else might you have done?

Unfortunately I went to a public high school in California that didn’t have much of an art program, but I do remember the one thing I would get praised for is doing my covers for book reports with elaborate drawings that illustrated the novel. Once again, more crayons, less writing. I was always drawing, but in high school, my real passion and obsession was surfing, something that, to this day, is still equally important to me.

I love the lithographs you made with Rasmus at Edition Copenhagen. I got to see them in person this summer when I worked with him myself. I was curious if you have made a lot of prints before because they work so well with your work. What was your experience like going there?

I’m so happy you ended up going and working there as well, they said how much they wanted to collaborate with you. Working with them was wonderful. It’s a medium I’ve never worked with, and honestly, without their help, it’s not a medium I would embark on again. I loved the results and I love the infinite range of what is possible in printmaking, but I think that I naturally gravitate to things that are more direct, like working in paint and clay. We should trade prints!

I absolutely would love to trade with you. I love the intimacy of your smaller paintings but am always impressed you are able to achieve that in your larger panels, as well. Is there one size that feels more comfortable to you? Did you ever have to force yourself to change it up to get out of your own comfort zone?

Initially, when I started painting on wood instead of clay, the largest paintings were 3 x 4 feet and the smallest were 9 x 12 inches. And, indeed, over the years, with more confidence and demands from larger gallery spaces, the work eventually evolved into larger format, some up to 9 x 12 feet in scale. In general, I like to hover between both worlds, sometimes making small paintings with a small brush and other times confronting a larger-than-life canvas and the physicality that comes with working on that scale.

I noticed that you are very creative with where you install your paintings in the gallery and even in your studio. Some are placed quite high up and I’m always wondering what your thought process is in creating the space for the work to be viewed. I like that it’s not a conventional way to look at paintings. Do you do a mock-up of the space ahead of time or am I reading too much into it?

Like you said, I have some small works, intimate in scale, and larger, more massive paintings co-existing in one show. When installing a show, I like the idea of considering the installations almost like a constellations, where certain works are clustered together, and other works are more isolated or hung higher up on a wall above eye level, to create a kind of visual symphonic movement. These free associative narratives that happen between paintings is what interests me, their polarities and the dynamic of their relationships to one another. I like setting up different possibilities.

Jules de Balincourt’s recent collaboration with Girl Skateboards will be in stores in early November 2017. He has an upcoming solo show at Victoria Miro, London, in January 2018.