Julie Curtiss

In Her Wildest Dreams

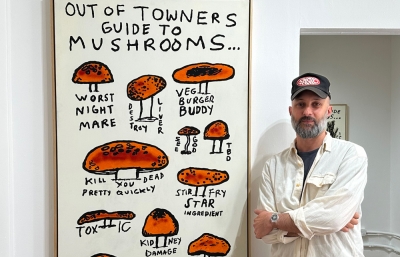

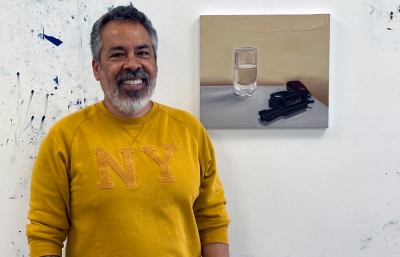

Interview by Charles Moore // Portrait by Dan McMahon

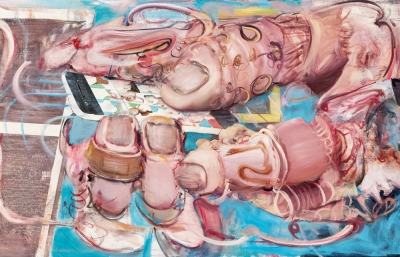

Raised in the eastern suburbs of Paris, abstract painter Julie Curtiss stands firm in her belief that the Covid-19 pandemic has forced people to look at themselves. While she’s adamant that the rippling effect of the devastation taking place in 2020-2021 is temporary, she claims people can’t understand what’s happening collectively without looking inward—and that perhaps, by taking the time to self-reflect while stuck at home, we can pave the way for a better-informed and more connected future. Let it be said that the New York-based artist isn’t political in the broad sense of the term. Her work is rooted in the female identity, focusing on vibrant close-up paintings zoomed in so close the viewer inevitably becomes lost in her large-scale canvases. Showcasing the fine line between inspiring ideas and summoning questions, Curtiss creates both overwhelming nuance and in-your-face specificity that jointly encourage observers to project their own experiences into the art they’ve come to appreciate. Ambiguity is key, along with the paradox of the human experience. These, of course, are pillars of Curtiss’s work.

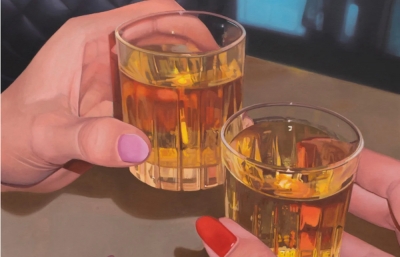

Brought up by a French mother and a Vietnamese father, the artist—an only child—visited museums on a regular basis in her early years. She found herself infatuated with Degas and captivated by much of the late nineteenth century; in this same vein, pulling stillness from movement plays a key role in her own work today. The artist has lived in France and Germany, Japan and the United States, working with the likes of Jeff Koons and Brian Donnelly (the latter known as KAWS) before making a name for herself. In 2004, she studied at the Art Institute of Chicago by way of a Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy Award, subsequently earning her degree from l’Ecole des Beaux-arts in Paris in 2006. It wasn’t until 2015, however, that Curtiss cemented her signature style composed of faceless portraits, skewed digits, and curved bodies masked by thick hair, macro-representations of food and drink, and seemingly simple life objects.

Ask the artist what motivates her, and she’ll cite psychology; now in her 30s, Curtiss has been in therapy since she was 16. The painter explains how everyone possesses a shadow which is integral to the self, and that incorporation of the shadow into the work can be largely therapeutic. Since the shadow represents the darkest parts of a person’s being, she has set out to capture this sense of other by way of projected experiences.Through her paintings, Curtiss endeavors to serve as the viewer’s own shadow, culminating in an experience emblematic of gazing through a screen, forcing introspection. Featureless beings, isolated body parts, accessories and food warped into abstraction in contrast to frequent monochromatic backdrops all comprise elements embraced by Curtiss. And, at this point in time, it is certain that Curtiss has given the female identity an innovative, grotesque, and utterly human overhaul the public has grown to love. “I get really excited when people really see art as it really should be,” she says, “the most successful art pieces are when people get something from it that's spiritual.”

Charles Moore: So you grew up outside of Paris. Tell me about those early years and your earliest experiences with art.

Julie Curtiss: I grew up in Les Pavillons-sous-Bois, which are the eastern suburbs of Paris. There's a lot like what you would call the “projects.” It was more a residential type of area, a bit different from Paris itself.

My mom is French, my dad Vietnamese, and so I felt I had kind of cool parents. My dad was a really good photographer and my mom was always interested in art, so they brought me along to museums and we traveled quite a bit. I had quite a liberal upbringing. I remember going to the museum and being really into Degas because he painted dancers—and I really loved dancing. All those late nineteenth-century works really captivated me.

When did you first learn that you had the talent for drawing or painting?

As an only child, I was naturally inclined to drawing and all kinds of crafts. I’m glad my parents encouraged me to pursue whatever I had a fancy for. I would just lose myself in it and be captivated by the flow and mood of the moment.

Is that why you decided to go to art school instead of a more traditional university?

Yes. As a teenager, I experienced a lot of anxiety, so I used art to channel my nervous energy. Art was also my favorite subject in school, too. So, naturally, I wanted to get into art school. There were never any other options, and my parents were always supportive. My mother was always very savvy, so right away she was able to find a suitable prep class that was also free. It was experimental, but it was really good and enabled me to get into more recognized art schools of my choice later.

The French system is different from the American system. If you want to go to a public school that's free, you have to qualify for admission, and that can be pretty difficult. From then on, your whole education is assured. So I attended the Beaux-Arts school in Paris. Beaux-Arts really intimidated me at first because it felt really elitist. But I got over that.

I was actually looking at your CV and it seems like you jumped around from one art school to the next. You went to Germany and then Chicago and then back to France. Tell me about that experience.

Do you know that you can apply to art program exchanges with other schools? I applied first for one in Germany and I got into Dresden, which was very competitive to get into but I made it. Then I came back to France and obtained a sizable grant from LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton). The grant enabled me to study abroad; I had already done one exchange program, and this was the second. So I went to Chicago, which totally changed my life, and it was amazing.

How so?

American culture is so different from French culture in every way. For me, it was pretty liberating to be in Chicago and discover the American subculture. It was also here that I met my husband, Clinton King. Just being in Chicago made me realize that I just wanted to spend more time in America: I was learning so much here, I felt so free.

But you did go back to France, right?

Yes, I went back to France to do my MFA, but it was so far away from my husband that we decided to be in Japan together for a year. We eventually returned to Paris, but decided to try to make it happen in New York.

Was your first job here in art?

No way! I worked in a coffee shop and then in a shoe store, so I moved from $11 to $14 an hour. Eventually I found my way to Jeff Koons. This was a really huge upgrade and I couldn't believe my luck getting there.

What were you doing for Jeff?

I was working in the sculpture painting department, masking sculptures, which I enjoyed because Koons’ sculptures are amazing. But I didn't stay long because it was a full-time job and I just didn't have time to do my own art.

Didn't you do any art at the time?

I definitely kept doing it but that meant a lot of work. I’d go back to my studio and work through the evening and on weekends. I worked seven days a week. But that's what I like about New York—the people are so driven! After a year, I managed to get a small art residency. I finally found a job with KAWS for Brian Donnelly; this was a turning point.

What were you doing for him?

It was a smaller studio than Koons’s, a much more intimate, hands-on and supportive atmosphere. I was only required to work four days a week, so had more time for my studio. That was such an invigorating experience.

What was your work like then, and how has it evolved since your early years in New York?

I've tried so many different things, but the constant is that I've always worked more with images. It was more Degas and figurative work in the early phases. But when I moved to New York, I focused more on works on paper that were really graphic—comic-bookish, if you like—but with big compositions, almost abstract. It was really the line, that strong upward line I used that actually caught KAWS’s eye: somehow he thought we did relate in some strange way. Of course, my style evolved once I started to work for Brian, because I really liked his work.

I definitely see the correlation between your work and Brian's, especially the meticulous lines and unique figures. But I'm also looking at what you said in one of your other interviews about exploring the enduring influence of surrealism through the female gaze. Tell me about the female gaze.

Well, the idea is re-exploring canons of art in terms of female archetypes and figures. You paint from the inside and on the outside too, bringing in all your influences, which sometimes involves borrowing someone's gaze of the artist or the culture.

You also think from the perspective of the viewer to the objects that are being displayed. The female figures being presented are far from passive. There's something very active about displaying yourself, curating yourself, presenting yourself to be seen, to be an object of adoration—or whatever I envisioned to be active and creative about that display.

I remember when I started this body of work, I was really interested in finding my own voice and exploring different aspects of my psyche in relation to society. This was in the medium of visual language, that age-old argument of what it means to be a woman at a given time in history. At the time, I was just a nobody without an art career. I was just really trying to find my way, and I hadn’t sold anything. Again, figuration wasn’t big at that time. Abstract was still the big thing.

That must have been tough.

When you don't have a career, there are often thoughts that having a child would bring fulfillment. At the same time, you wonder whether you should be sacrificing something that’s really important.

So, you had to make a choice.

Yes, I was really torn, but I was really drawn to all these questions swirling in my head.

On another subject, your work is considered to be surrealistic, which is often described with terms like “untethered from reality,” “dreams and the subconscious mind,” “automatism” or “pushing back our conscious mind” to make room for the work. Tell me what these things mean to you.

I can’t say precisely. My work may be interpreted as surrealism, but I don’t think I consciously sought to define my work primarily in that way. But the element of surrealism is there because I would take the image, push the boundaries and use it to question perceived reality as well as my own.

At the beginning of my art practice in New York, it was this very sci-fi kind of landscape that was very graphic and trippy. Every scene appeared to be made of intestines and internal landscapes—but, at the same time, I was aware I was thinking myself into a corner.

Who are some of your influences?

One major influence is one of my favorite Surrealists, Robert Greenwell. But there’s an area in the politics of the Surrealist movement I've never been into. I think people forget how political Surrealism was, how much of a chaotic and anti-establishment kind of movement it was from the beginning.

That’s true. I interpreted your work as more of a juxtaposition of unexpected objects, but do you feel that your work is becoming more political?

I've never been political in a strict sense. There's a fine line between inspiring ideas and exploring new perceptions of things, and becoming political in terms of advancing a really strong agenda.

So you had different priorities?

Yeah. I want people to still have room to project some of their lead experiences or some of their inner world into my work, and I want to provide enough ambiguity that portrays how ideas are often complementary. I’m more interested in paradox, and in how things can reverse in one second. Something that's too political in the classic sense just doesn't allow for that shift.

Right, I get you. Moving on… hair features prominently in your work. How do you utilize it as an important element?

Hair is a substance that is growing, that ties us to a primitive form of life and possesses a duality, especially for women. When it's on our heads, it can be perceived as quite exquisite, but when it's on the body, all of a sudden it's considered unsightly.

Do you feel like you have something of a Medusa complex?

Medusa was my favourite mythological story as a kid. It fascinated as well as scared me, and it brought on these weird dreams.

I have this dream, where I’m working in a temple thinking it must be secret art—for me, that’s a Medusa complex. You know, the foreboding that a fixed image or a fixed rendition of something has the power to turn you into stone. It’s so strong it can kill me. Most of the time, in that whole gaze paradox with Perseus and Medusa, Medusa is the embodiment of that kind of duality between good and evil. You see, Perseus uses her head to turn it against his enemies. So she was really a symbol of duality, both the illness and the remedy.

How much do dreams influence your work?

Art comes from a dark place, and I find a lot of darkness in my dreams. When I started therapy, dreams would be part of the therapeutic method. I always paid attention to them and so does Clinton, who always writes them down. Occasionally, I get what's called a luminous dream, where your unconscious is trying to send a message through the dream.

But, more importantly, it is the place of intuition. I'm not a cerebral or intellectual person; I try to pay attention to my instincts, and I think dreams are one expression of them. My instincts direct me to have a flexible state of mind when I walk in the street or when I go to museums. Ideas pop up because I do entertain the imagery and associations triggered, and know how to nurture them so they can evolve into a life of their own. But it has to be spontaneous. When I analyze too much, they lose their potency.

Most of the work I saw involved a lot of facial hair as well as women’s fingernails. I feel like there's a little bit more emphasis on the body now.

Yes, there’s more of the body. I have been working in a cinematic way of cropping, chopping and segmenting the body, like a puzzle. I crop to bring out the mystery. Now I just want to change the general framing to a wider angle. I was thinking more about how the individual relates to the collective. This is the new body of work that is tapping into those broader ideas.

I also feel that literature informs a lot of your work. You’re currently reading A Beginner's Guide to Constructing the Universe: The Mathematical Archetypes of Nature, Art and Science. Is this part of a series?

This book says where you are from 1 to 10. It’s basically how the universe is organized according to different scales, whether through biology, physics or mathematics; not just how things are organized, but how they can be used to create myth, which basically communicates knowledge. Then there’s myth through archetypes, meaning images that unify knowledge into one whole in terms of people’s age, symbolism and religion.

The number one, as in unity, the cell, the circle, or God and the universe, recurs all over the place. And art reflects that recurring theme. What’s interesting is that the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s painting of Adam and Eve being cast out of the garden is about being aware of whether you’re naked or not.

Tell me about the shadows.

Everybody has a shadow, which is the dark side of oneself. We can't look at our own shadows. It’s like you're projecting your own shadow onto the other person, and that's what the paintings depict—how they are each other's shadow as they look through a screen. How can you pretend to understand what's going on in the world if you actually don't know your own self?

What about the food pieces?

Those are hyper-realistic, but definitely uncanny. I made a bunch of sculptures when I was in a residency in Japan using some of the materials they use there for their food displays, like fake seaweed or beef.

I've always needed sculpture to fall back on just to keep experimenting, to keep everything fun and alive. The thing with the sculpture is that I'm having a lot of fun, but it also feels less resolved than the paintings.

So, you think that art should be enjoyed?

Yes, and I get really excited when people really see art as it really should be—a truly enjoyable experience. That is why I really like pop culture. For me, the most successful art pieces are when people get something spiritual from them. The beauty is being so engrossed in the moment that you are almost unaware of that transformation,

In closing, what do you want me to know about you or your work that hasn't been asked already?

Nowadays, I find it harder and harder to really open up ideas because somehow I think artists are wary about new audiences and offending them.

I would prefer that we just tell it as it is; we don’t need to cast a moral spin. I find it really hard to do that because there are uncomfortable subjects that are also very important and should be addressed. In fact, where there’s discomfort, we should actually go straight for it, so you definitely don't want to linger over the matter, but settle it. But I think that’s really difficult in today’s cancel culture.