Kerry James Marshall

The Key Figure

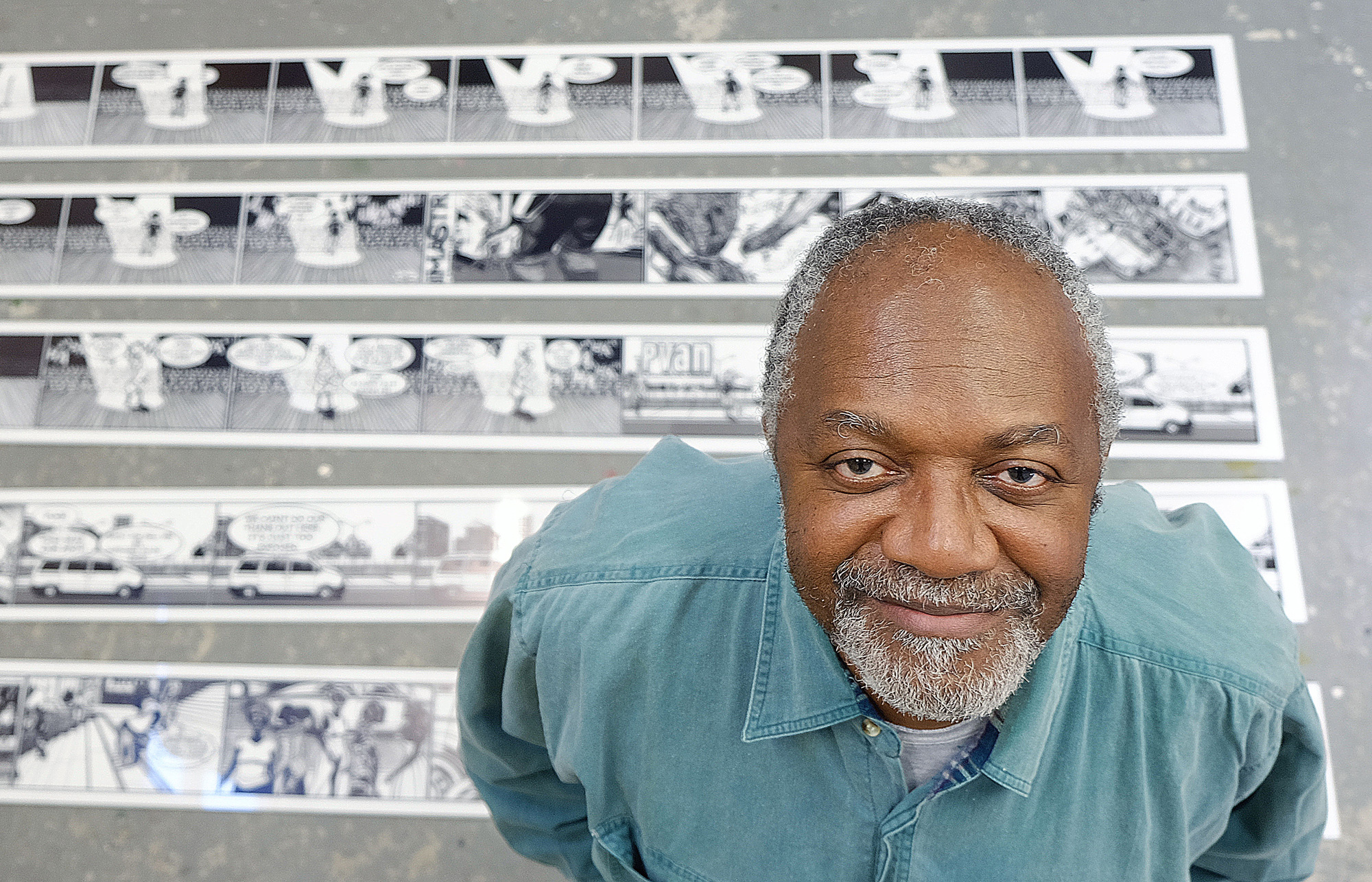

Interview by David Molesky // Portrait by Joey Garfield

In 2016, the Kerry James Marshall retrospective, Mastry, traveled from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (MCA) to the Met Breuer. Standing behind the clear plexiglass podium, about to address the press, Kerry took a deep breath, looked down, noticed his descended zipper, corrected it, and then delivered his wonderfully disarming chuckle, effectively deepening the awe of the already starstruck audience. The exhibition fulfilled his biggest dreams, he explained, his work now in the Met alongside his own selections of great historical artworks from the museum’s permanent collection.

The first room of the retrospective was breathtaking, with nearly a dozen unstretched canvases as large as 10 x 18 feet, painted with thick unblended passages, fixed to the wall by rivets. These masterworks of narrative compositions are astutely conscious of flatness, illusion, and draftsmanship, with dynamic brushwork and colors that freely incorporate comics and pop culture as much as they sample the grand tradition. The retrospective presented his entire oeuvre, including portraits, lightboxes, sculptures, photography, and comics called Dailies.

Perhaps even more inspiring is how Kerry’s life path has provided the key ingredients for his ever-expanding creative universe. Born in 1955, Kerry moved with his family a decade later from Birmingham, Alabama to Watts in Los Angeles. During an era of rising racial tension, they moved a few years later to a housing project called Nickerson Gardens, just before the historic Watts riots.

Kerry knew early on that he wanted to be an artist and was selected from his Junior High School to attend advanced courses in drawing at what was then known as Otis Art Institute. While drawing a master copy of Otis instructor Charles White’s lithograph of Frederick Douglass, he had a realization about the insularity of white figures representing ideal beauty throughout art history. He’d go to museums to observe masterful technique, but his appreciation was hampered because of the dearth of black subjects who seemed excluded from the whole genre.

-HR.jpg)

At first, Kerry considered a career in children’s book illustration and also dabbled, like many of his peers, in abstract pictures. The Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison’s novel about a black man whose skin color renders him marginalized, inspired Kerry to make his painting Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self. This seminal painting re-energized the use of the figure as his vehicle to bring politics and race into focus. The painting became emblematic of a lifelong artistic goal to fill the gaps of history, where black historical figures and black cultural ideas did not have representation.

In his late twenties, Kerry took a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, the only museum in the US funded and operated by African Americans. In what was literally love at first sight, he would eventually marry the first person he met upon his arrival, the actress Cheryl Lynn Bruce, the museum’s PR representative at the time. Working and living in a 6 x 9-foot room at the Harlem YMCA that was once home to Malcolm X, Kerry solidified a determination to continue his work, regardless of what situation or space was available to him.

In 1987, Kerry, focused and unwavering, moved to Chicago and got a break when he was hired as an artistic director for a feature film. The salary afforded him almost a year of living expenses, spurring a significant body of work, and his momentum continues unflagged to this day. In 1998, he had his first major solo show at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago. Now, Kerry’s work is featured in an incredible roster of important museum collections, and he has been awarded an even longer list of residencies, grants, fellowships, and honorary degrees.

This past autumn, I called Kerry at his studio on the South Side of Chicago, and we talked about getting to work after the retrospective, and the exciting continuous evolution of his comic strip.

David Molesky: You must be excited to get back to studio life after the tour of Mastry.

Kerry James Marshall: The whole experience was satisfying, but I couldn't wait until it was finished, so I could get back to a normal routine. The problem with big surveys is that it puts you in a position where you have to start to figure out what your next act is going to be.

Especially when you've achieved so much, the bar gets raised again.

Right. It's a challenge to exceed yourself. Every time I do a picture, I'm trying to do a better or more complex picture from my last. I try to push the limits of my abilities. With retrospectives, you make assessments of what you've done over time. You can see it all in front of you. You know more about what you're trying to get at and how to make it happen. And it's hard to look at things you've done 30 years ago and not think, "Oh, if I knew then what I know now, maybe I would've done this a little differently."

As a painter myself, sometimes it seems the more I paint, the harder it gets. I have to account for more perspectives while I’m working. You ever feel that way?

Yeah, but you know what? That's the way it's supposed to be. It's supposed to get harder, and that's not really a problem. You're supposed to be more sophisticated and much more self-conscious. As you know more, you have to consider more. It gets harder to make the next thing, because you have to have a good reason to do it.

How do you think new digital and virtual mediums will affect the future evolution of figuration?

Figuration is coming back. It’s the foundation, but the reality was that it never went anywhere. There were periods where abstraction seemed more advanced. The issue is that it's not whether a thing is painting, photography, sculpture, installation, abstract, or representational. That's not really where the critical value of a thing lies. It actually has more to do with the particular treatment of each one of those different media.

The popularity of cheap instant cameras didn't increase the number of excellent images any more than going abstract made people better artists. When there is proliferation, it’s another case where it becomes more difficult, and you have to take responsibility to marshall all the philosophical ideas, critical conceptions, and technical characteristics. You have to figure out a way to maximize their generated effect. This is how proliferation makes it harder to do things that are worthwhile.

It seems with greater knowledge comes greater responsibility.

If you're not going to surrender to chance, then you're going to target your efforts at achieving a very specific thing.That's how you keep it going. You're trying to get at something specific, you're not just waiting for any old kind of thing to happen, or hoping that something you did was interesting enough, you're really trying to make it that way.

When you were teaching, you’d tell students, "You have to ask why, to ask why always." What were some of the important “whys” you asked yourself, and what do you think are some of the important questions that younger artists should be asking themselves now?

People are not driven to make artwork because of some of internal emotional need. I believe it's always because you want to participate in something that you see other people doing. When you look at the history of how what you want to do has evolved, you have to ask: "Can I add anything to it?" Or will I be satisfied just mimicking what has already been done?

.jpg)

In the ’70s, there was this notion that painting was completely obsolete. Would it be worth my effort to carry on a practice that people are claiming has already been exhausted? You have to ask yourself that in the face of what is going on around you. No matter what the technology or activity is, nothing has ever been completely exhausted. You can look around for those places that never got fully resolved, and then you can make an attempt at trying to resolve those things.

I came across an article in Scientific American about Fermat's Last Theorem. He was a 17th century mathematician who proposed a paradox that couldn’t be resolved for over 350 years. About 20 years ago, it was proven by a man who, at 10 years old, became determined to solve it. So there are these novel ideas that pose a challenge, and somebody's got to check if it's worthwhile. You can do that in the art world, too.

Contemporary history painting can shed new light on events by prompting a unique space and time for contemplation. How have current and recent events made their way into your work?

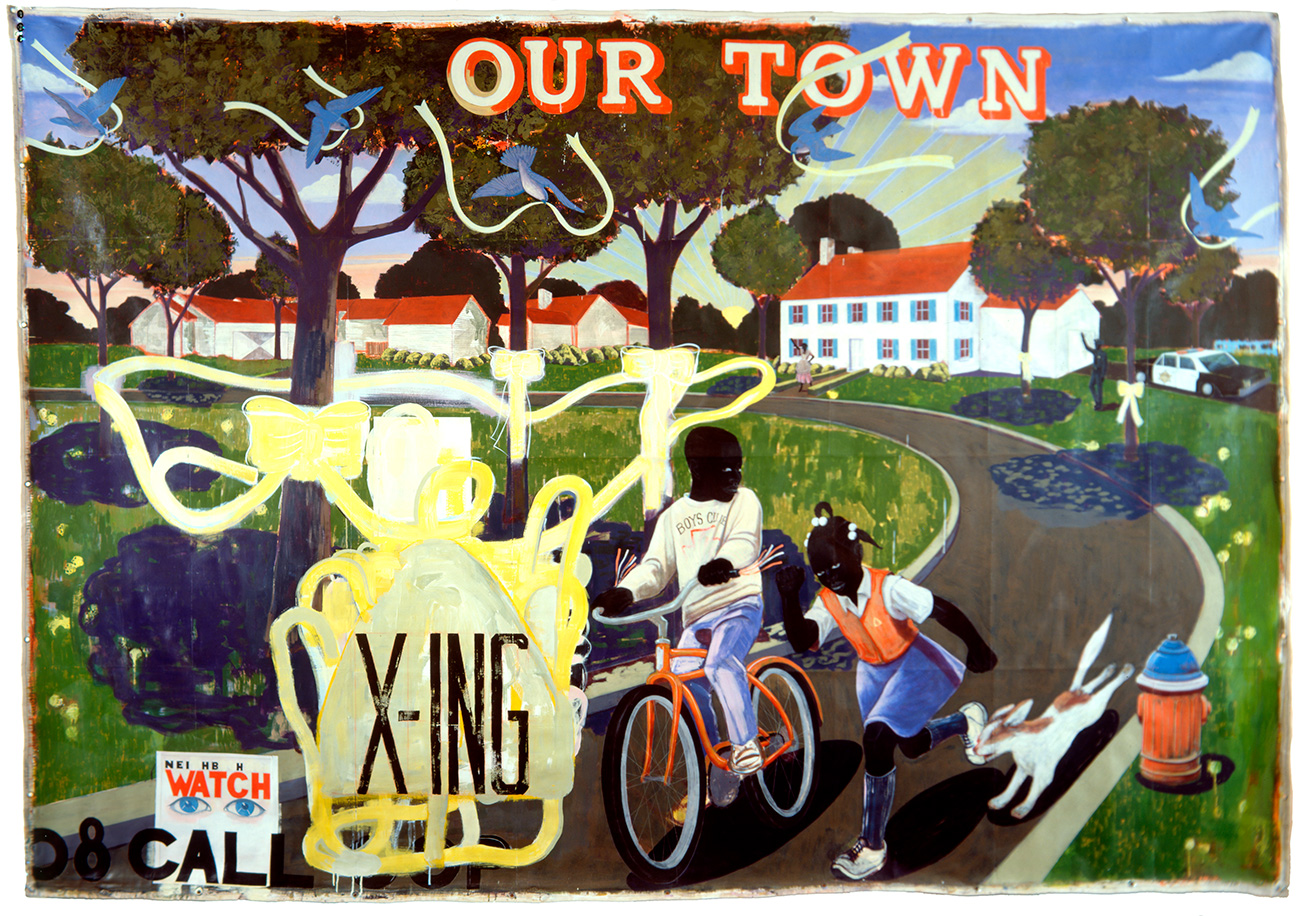

The idea for Rhythm Mastr began with two recent catastrophes: the spike in violence in Chicago in the ’90s, and the demolition of high-rise public housing near where I live on the South Side of Chicago. There were moving people out and tearing down public housing. It was controversial and complicated in how it was handled. I want the narrative around these events to take on Homeric epic structure and form. I realized how this could have the same cultural impact as Star Wars, which initially was going to be five episodes, but now seems to be going on in perpetuity. The narrative allowed me to talk about the social consequence of high-rise housing and its demolition, as well as the consequences of gang violence in relationship to public housing projects and the surrounding neighborhood. It also gave me a chance to talk about the conflicts between tradition and modernity. The public high-rises on 35th Street were right across the street from a Mies Van Der Rohe-designed campus for the Illinois Institution of Technology (IIT). The street literally divided two completely different worlds.

I have a character from the neighborhood in a program learning robotics at IIT, alongside a young man who lives in the projects. Also in this neighborhood is a brownstone building called the Ancient Egyptian Museum. This museum promotes the idea of Afrocentrism, where black people become healthy and gang violence stops when black people can revive who they were before they were enslaved people. To do that, you center your worldview around Africa and center creative capacities around the achievements of the Egyptians. In the narrative, the robotics student is the girlfriend of the kid who meets the Rhythm Man who teaches him drum patterns to unlock the power of African figure sculptures. They are both trying to solve the gang war problem. They don't realize that they're in conflict with each other: one using robotic technology, the other using African mystic power.

What is your vision for the development of the graphic novel?

For me, it needs to be something that operates like The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, or the Harry Potter cycles. You need to be able to get that much out of it. It needs to demonstrate that you can generate these narratives that can go on for generations. Its initial inception was for the Carnegie International, but it really started to take shape when I did a show at the MCA (Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago) where it became a daily comic strip called Dailies. I began building a series of comics around the Rhythm Mastr. Each component of the overall narrative allowed me to talk about things through barbershop-style conversations about history, culture, and politics.

There was one thread that started out as Ho Stroll. With a lot of prostitution and streetwalkers in the neighborhood, I had to give these working people a chance to contribute their inner philosophical life through conversation. So it really contains three narratives: the Rhythm Mastr, P-Van, and Ho Stroll, which has now become On the Stroll. I was going to build up enough narratives to fill a full-size page of the Chicago Tribune with black-oriented comics.

These separate narratives overlap and become the larger Rhythm Mastr story, with everything taking place in the same neighborhood. The Rhythm Mastr kids would pass the P-Van, they’d see the prostitutes on the street, they’d go by the Ancient Egyptian Museum, they’d be at IIT, and they would be at the projects. All of it gets woven together.

.jpg)

I'm still working on it. After the Mastry show closed, this was supposed to be the year that I would resolve the graphic novel form. In this process, I'm always making new factions of those stories and I'm actually in the middle of working on new Dailies right now.

What is the overarching plot for the screenplay?

The theme is really the conflict between tradition and modernity. In a drive towards the future, can an orientation to the past win?

It's possible to use values from our past that will remain important to our species in the future.

Yeah. This is something that people miss when talking about painting and all of its accompanying skillsets. I don't know of a good film that didn't start out with the production designer making drawings of the sets. That’s the same skillset needed for narrative paintings. It's a complete miscomprehension to believe that you don't need to do the same things that Rembrandt was doing. You have to think about how the lighting works. You have to conceive, construct, and refine the narrative. Look at all those paintings; there's virtually no difference between the setup for Gericault's Raft of the Medusa or a movie scene. You get actors posed in costumes with props, then find a location and organize it so that it conveys your ideas. I've never seen a movie that didn't do that.

When Rhythm Mastr becomes a movie, do you think it'll be animated or do you think you'll use real figures?

Ideally, it has to be animated first. You have a lot more latitude that way.

Have you done animation before?

I've done some animation and video that uses animation. When I was in high school, I participated in a program at Otis called "Tutor Art," which included hand-drawn animation. I learned how to do animation to a soundtrack. I also have every book on animation you can find. I watch all the Disney and the Chuck Jones documentaries. I'm really interested in technique. I did production design for a couple of feature films, so I know a little bit about how films are made and how animation is done, so I'm ready for it.

Any idea when folks might start hearing about the graphic novel coming out, or the animation?

By this time next year, I hope to have the graphic novel ready for publication. This project first came into existence in 1999. It takes a long time. If you're really going to do it right, you really have to come to terms with the amount of detail that has to be invested in everything. When I started developing characters for the comic strip, I designed clothes with my then assistant who was also a fashion designer. This was just one part of building the archive and style that would ultimately be the graphic novel. In my studio, I use set pieces to development the narrative. You have to invent practically every detail, so I have models of all kinds of things to draw from, including downtown. It gets more exciting as it comes together. It propels me to keep going, because I can see it being fulfilled. When you're in it, there's nothing but hard work. There's nothing but labor. And it's almost all physical.

Any concluding advice for younger artists?

There are some things that you can't even imagine unless you already believe you have the capability of making it happen. As you know more and have more skills, you can do more and imagine more things. That seems fundamental. I encourage people to do everything and take nothing for granted.There are no shortcuts.

Kerry James Marshall’s work will be featured in Figuring History alongside Robert Colescott and Mickalene Thomas at the Seattle Art Museum from February 15–May 13, 2018.

Images courtesy of Koplin Del Rio Gallery