Kristina Schuldt

Nothing Has to Fit

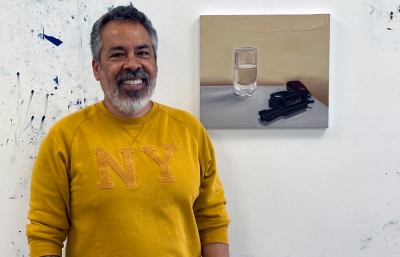

Interview and portrait by Sasha Bogojev

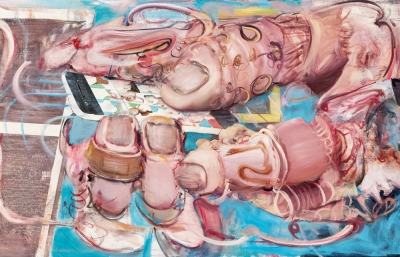

Rough and elegant, beautiful and grotesque, strong and fragile, vibrant and dispiriting, successful and failed. Such are the perpetual interplays that play with equilibrium in what we recognize as life. For Kristina Schuldt, they function as elements of a language through which she examines and seeks to explain about disorder, randomness, and uncertainty of everyday experiences. Her sturdy muses clutch withering flowers or valiantly navigate in high heels, pure metaphors for personal experiences, coded visuals that represent the human condition.

Schuldt recently moved from her old studio in Spinnerei, a renowned repurposed industrial complex in Leipzig, to the performance hall of a former cultural space within a small village outside the city. Located in the austere countryside of a former GDR, the building itself feels like a monument to the precarious, a state that both fastens and tears down everything from banal, everyday moments to the universe as a whole. Capable of seeing the humor, pathos, sadness and entertaining, Schuldt embraces this careening capriciousness as her ethos for her uniquely formidable paintings.

Sasha Bogojev: At the opening of your show at Drents Museum in Assen, you declared a belief that one person’s pleasure equals another’s suffering…

Kristina Schuldt: Yes, for me, life is really brutal. I'm painting here while people are suffering and things just work like that around us, as well as in nature. It's like energy that cannot get lost. It only changes its form.

You’re saying the laws of thermodynamics?

Yes. I think in a formal way, for me, flowers are like humans. When you pick the flowers, it's like when you fall in love—the moment that it happens, it's like it starts fading away. It begins to fade away. And the flowers, once you pick them, they start dying at this moment.

What do flowers symbolize for you, and why do you like using them in your work? Is it primarily visual?

What I like about flowers is that… they grow. Yesterday, when my son’s teacher told me that he was drawing penises, I thought about masculinity and I thought about churches too. It seems that everything is in this phallic shape. Also the plants and everything, the whole world is like that. So, yes, what I like about flowers is that I really like doing gardening because I like to watch the plants grow.

You referred to masculinity, and your work is obviously not about masculinity.

Maybe this is also this thermodynamic thing because everyone tells me I behave like a man.

What I like about female figures is that I can feel that. When I painted a bike accident, it was my bike accident, and I tried to find a form to make a pictogram out of it, because it's not my private thing that happened. I always think about a problem and I try to find how it can be presented universally or what it means in a bigger context.

What are some of the private things that informed your work and how so?

For example, the last year, 2020, was a really bad year for me because my mother died in the beginning. I was really, really suffering and I was longing for something good, but there was this whole Corona thing. So, when I was there, I took what felt really important, her gardening hat. Because the hat is a symbol of good times, for summer; then I started to paint hats. I'm really into hats now. I had this longing for these themes. I think this is how it works—it's always what's happening in my life that is influencing the work.

How do you go about switching the personal to the universal?

I just start painting and then something happens. It's like this evolution happens while I'm painting, both in the painting and in real life. I keep thinking all the time—what is it about? What is the context? What is the problem? And then I try to find the solution, like a key.

How much work do you have planned ahead when you approach the canvas?

I pre-plan nothing.

How difficult is that?

It's difficult, but it's also a luxury because I don't really have to do anything. It's like playing a game and I don't want to know the rules before.

Do you have a certain formula that you use when you approach a blank canvas?

No. It's when I start, I just know that anything I put down, will not last. And it's really, really frustrating. But there's a point where it becomes like a haptic thing. It gets a body.

I also do have a new trick. I’m showing you these colors, these jars of old tubes of paint from my grandfather from Russia. I always choose one color and put a little bit in the painting. I have this idea that the soul of my grandfather will be there and will help me to find this picture.

Oh, I really like that.

I don't know if that’s just in my mind. But then I also need to choose the color, and that is also really difficult and takes a long time. For example, this painting, which appears to be far from complete, for me, looks like shit. I have to change everything.

Does your grandad’s work still exist somewhere?

He was a painter and sculptor. He died when I was one year old, and I only have these old photos and some of his things, and I really like them. He was working in a social realism manner.

I always sensed that element in your work too, though it seems to take a few steps towards cubism or even abstraction. What appeals to you about that?

I always have the problem that I cannot decide. When I finish a body of work, then I am thinking about being more realistic or more abstract. I cannot decide, so I do both. I try to do both. Also, I think I'm connected to everything. I don't want to set any borders on myself. I think today you can do everything. You can exercise or use everything. So, with the Internet, you can find and use everything.

Does that get frustrating?

Yes. But I think that it's normal, because it’s hard to have an idea about new things. It's always a combination of things that already exist. Yes, it's a problem and I would be really happy if anyone finds something new or invents something new, but until this happens, we all have to just do what we’re doing. For example, my work is always compared with Fernand Léger, and yes, I have phases when I'm really into something. This year, I admired an Austrian painter, Waldmüller. I bought this book and it's a little bit kitsch, but I was really into it. I don't force it at all, but it just happens that I realize after some time that there's something from it that seeps into my own painting.

I saw Léger and Tubism being referenced, but you’re going in a pretty unexpected path with your colors. They're not flashy colors in any sense, so how do you choose them?

It's a really long process. I keep changing the colors and looking at how it works. When I work, I have this feeling that it's all really boring and there are no new colors. I need more. Even when I'm buying colors, it's like, "Well, that's so boring." So, I always try to make a new combination so the colors look different.

It must be pretty difficult to start with nothing and go towards the finished piece and all those color combinations. Do you impose restrictions or certain methods to achieve the goal?

One restriction is when the painting is out of the studio, nothing will happen. It's really dangerous to let the painting stay here. I have this one motto, but I keep forgetting about it! So when I remember, then I have fun again. It is—“nothing has to fit.” It's really fun because most of the time I'm only thinking, "I'm a loser. I cannot finish at this stage. I'm really weak. I can do nothing. Everyone is successful and everyone can paint." And then I remember this motto and then I start having fun again.

That’s pretty awesome! So would you say you work better under pressure?

Yes. I work better when I have deadlines. But then everyone gets crazy around me, my family, and everyone. Everyone becomes an enemy. While I'm working, I'm a real monster.

So the collage elements evolve from “nothing has to fit”?

This also came from the working process. I just tried it and then I thought it’s really nice. So, I can use this, and normally these things are laying around everywhere and they're also dirty and with some other colors on them. But for me, they're really sacred. So when I paint them in the picture, I get to keep them.

And when you said that it comes from the working process, what does that phase look like?

It's mostly about trying things out. Sometimes when I have a hand that is painted on a sheet of paper, it should not be a real hand. It's only a hint that there could be a hand. Or maybe a head that’s not a real head, only trying to be.

So you don’t use the computer in any part of your process?

No. Sometimes I use photos of my own paintings and cut them out, and I started using photos from a magazine. And they can be like meditation too because, when it's really chaotic, and you are really in crisis, painting a realistic part like that calms down the whole thing. When you paint slowly, that calms the whole painting.

The images are always fragmented. How do you approach that?

I think sometimes I wish that the painting would be like a film, like a movie. When you make it fragmented, it gives a little bit the feeling that it's moving, that you’re watching something from different perspectives. Also, when you remember something, I think it's also fragmented. This is what it's about in oil paintings, always thinking of something and then finding a picture to save it, and to make it a universal thing that everyone can understand.

And what’s with the shoes and focus on the soles? It's a very recognizable element from your work, so I feel there must be something very symbolic about the image.

In the past, I told everyone that shoes are really important because I'm a Virgo. I'm an earth sign, so it's really important how I stand on the earth.

I'm also a Virgo!

Yeah, it's the best… But then also, I'm really into shoes. I like the heels because when you have high heels, it's like you lost your connection to the earth and it's really dangerous. You can fall down. You can fall down if you lose this connection tool. These faces with shoe soles are like real contrariness. The sitter will not say anything. I think in Arabic, Muslim, Hindu, or Buddhist countries, it's a really bad, bad, bad thing to show the bottom of your foot or shoe. So I thought about making a portrait, which is really antisocial. It says nothing and doesn't want to say anything.

I didn’t make that connection, but it’s an intriguing concept. What about the other elements that suggest traditional femininity?

I really like this idea of making up. Like a young woman who's really dressing up and then the moment comes, and she chose the wrong shoes or the wrong dress. I particularly like skirts because they are like flowers. But there is no border for me there. I would also paint other clothes and I also started painting men, but it's really difficult to find a form because I cannot feel it. I can only see it from outside. I have many, many different shoes around, so I always change them because when you change the shoe, the whole painting is different.

The skirts flow and the heels are high, but there’s also an unexpected stubbiness? I’m sure it’s on purpose.

Yes, I really like these legs, which are like columns. And I also imagine that the legs transform into columns. I had some columns in the last paintings. It's a thing about stability and energy pathways. I cannot imagine painting thin legs. Maybe because I'm half-Russian so I want to have more, more… [laughs]

Do you feel any pressure working in Leipzig since it has such a strong reputation as a painterly mecca?

I think I never wanted to be quite a part of the New Leipzig School. But when I started studying, the first exhibition I saw was the diploma of Christoph Ruckhäberle and I remember that I was really impressed. But no, I don't feel under pressure because, at first, I didn't study with Neo Rauch. We were the idiots, the idiot class.

Ha! Was that the official title of the class?

No, no. I didn’t work in the academy; I worked in another building, not in the city center, a little bit outside. So, we could go there at night and in the day, and it felt like working in a village. Then, when I changed classes and was in the Neo Rauch class, I was still the idiot, coming to this meeting with house shoes, always too late. I was the only woman in the end and no one was expecting anything from me. So this was really good.

There was a lower standard for a woman?

Yes. It's the best starting point. So, I always did my thing and was not under pressure.

To what degree did your art education influence how your painting process?

The only thing I was taught, I think, is to think about it, that the context and the form have to go together and how you paint is also really important. It's like giving that special energy to the painting. This is really esoteric, I know, but I believe in it.

Oh, I think I understand what you mean. Are the switches between techniques within one work also part of this energy transfer?

Yes. I try to find the right form for everything. Even the music I’m listening to has to match.

What are some other important things you took from your art education from that period?

What I did was finish all theoretical things in the first year, and then I was only working in the studio. I think the most important thing is that you can be alone in the studio and never give up and always go on. Always go on. And the time with Neo Rauch was really interesting because he started at one corner and went to the other corner because, again, the composition and the context have to go together.

And how did you actually end up in Leipzig?

It was all really a coincidence. I was born in Moscow because my parents were studying there and then we moved when I was three to the north of Germany, next to the Baltic Sea. I came to Leipzig only for the first test at an academy. Maybe if the Berlin test were before, maybe I would go to Berlin. I only knew one book about Leipzig graphics, like advertisements and placards, and then someone at the test told me about the professor, and so on. I was like, “Is this important?”

Here we are today with you having a museum show in the Netherlands, and then another one in Germany. How does that feel? I guess people see you in a bit of a different light.

Yes. It's a big, big compliment. I realize that people are much nicer to me. And my father is really, really proud. Yes, it's interesting when you see paintings again because most paintings go away really fast and you will never see them again. In the museum show, you see your own paintings, and this show in Assen, it's like a retrospective. It's really old paintings inside. It's also really interesting for me to see my own painting.

Do you enjoy seeing them all again? I can imagine that looking at past mistakes and past successes, coupled withe with today's experience, can be challenging.

When you make a painting, you know every centimeter of it. So when you see it again, it feels familiar, like seeing your old friend. But I still wonder who did this work and I can never remember where I found the key for that. Because, sometimes, you go for a walk outside, then you have an idea; or I am walking in the studio and searching for something and then find a solution. But later on, I cannot remember how I solved the painting problem.

When you say "solve problems," what do you mean by that?

I try to understand what it's about, why things happen. Because I have this feeling that when things happen, you have to think about them and it's like a hint. I cannot understand it in this normal language. I have to transform it into a painting language to understand what it's about. Like, speak in another language.

Is it easier for you to communicate in that painterly language rather than an interview like this?

When I talk to you, sometimes I have the feeling, but I have a blackout and I have no idea how to express it, no answer. But in painting, it feels like it's my language. Everything is familiar. They're my props here and I know them.

So, you're not a big fan of talking about your work?

No.