Laurena Finéus

Love Letters to Haiti

Interview by Charles Moore // Portrait by the artist

Canadian visual artist Laurena Finéus showcases her Haitian heritage in figurative paintings. Now an MFA candidate at Columbia University, the artist relies on early memories of her childhood in Ottawa and Gatineau, stories from her maternal grandmother in Haiti, as well as a keen interest in alternative historical production to bring her compelling scenes to life. She infuses real and imagined subjects into near-whimsical landscapes, Creole, English, and French are blending into the titles of her works, baking in her cultural range. The artist leverages an intuitive color palette, something around which she admits to still building a narrative, further connecting with her lineage while creating intuitive spaces for the viewer.

Finéus speaks openly about the extent to which others have tried to silence the past in many Black communities, discovering that some have tried to fictionalize or omit those darker parts of Haiti’s history, allowing those in power to dictate how others are remembered. She hopes to reclaim this narrative through her paintings, offering a more impactful, more honest, if you will, take on Haitian culture. Though the public may feel repelled by the concept of nostalgia as it relates to their own country, Finéus wants to capture her lineage more objectively, honoring the place where her family put down roots before relocating to Canada. Issues around fear of Black governance, the condition of asylum seekers in America, and neocolonialism all serve as entry points into her research and define why she has turned to Haiti as a packed subject. Applying swaths of captivating blues, greens, and purples, the artist paints scenes of people simply communing, dancing, standing, swimming, spending time outdoors, gathering over rice, beans, and drink, and including more politically and historically charged imagery shrouded in the Caribbean landscapes.

Now based in New York, Finéus reflects on the beauty of growing up in the Black diaspora in Canada, a personal experience that underscored how rich and diverse a person’s idea of Blackness might be. The artist observes a more unified notion of Blackness in the U.S. and while she appreciates this sense of unity, she learned to identify with Haiti specifically while living in Canada. Today Haiti is exclusively absolutely elemental to her artistry, in work where Finéus strives to depict the darkness behind the exoticism. The nation of Haiti is visually stunning, culturally rich, and tied to the Caribbean, yet the historical lens through which it is so often portrayed isn’t entirely honest. The artist explains that the nation is often misrepresented, and far too often subject to needless foreign interventions. Inspired by her grandmother’s upbringing and migration, Finéus paints an expansive picture of life in Haiti, presenting a more truthful gaze.

Charles Moore: Laurena, perhaps we could start by talking about your background.

Laurena Finéus: Well, I was born and raised in Canada, but my origins are Haitian. This is really my rooting ground and where a lot of the drive in my work is derived. I have been moving around recently but I spent a large part of my life in the Ottawa-Gatineau region.

Tell me what it was like growing up.

I was raised in Gatineau, Québec, by my mother and grandmother who migrated to Canada in Hull, Québec, from Haiti in the 1970s. Both were single parents. Gatineau is located on the northern bank of the Ottawa river, both part of what we call Canada’s national capital regions, also known as Ottawa-Gatineau. But culturally, they are quite different, especially when I was growing up in the early 2000s. Gatineau had a very small homogenous and close-knit community that was mainly French-speaking at the time; however, it has changed rapidly and grown with a flux of recent migration, while Ottawa is much bigger and is primarily English-speaking, therefore, more ethnically diverse.

Growing up in Gatineau, I realized that there were probably five to ten other kids of color in the entire school. It was just this white world that we all had to contend with regularly. which now that I look back, was quite violent for a young black girl. So, when the earthquake happened in Haiti in 2010, it somehow triggered a wave of unwanted reactions toward me from my teachers and classmates in middle school. Every teacher would make it a point to acknowledge the crisis in the classroom which made me feel especially self-conscious. It was the first time I dealt with such a tragedy, and I simply didn’t know what to feel.

Case in point: following the earthquake, I was mostly detached from the catastrophe because all those images of pain and violence were suddenly thrust upon me—I couldn’t handle it. I think that's when I purposely had to disconnect. Even in conversations with my mom, I think she alienated herself from the crisis. She really would not want to talk about it even though we continued to live within the Haitian tradition like the food, the music, the culture—everything.

And were things different in Ottawa?

Absolutely! When I moved to Ottawa, where a major part of my family lives, I saw a huge contrast. First, I was amazed to see how diverse (in comparison to Gatineau) and confident my other family members were in terms of their Black identities and how seamlessly they navigated the western world.

There was this strange and numb, in-between safe space I had lived in for a long time until I moved to Ottawa. Here I had access to the rest of my community. That's when I was able to start realizing certain aspects of the diaspora and became part of a bigger universe and begin my interest in our culture. We would have little get-togethers among ourselves, as well as all these big familial events. So now that I moved to Ottawa, I have begun to feel more and more included in community living. Even though Ottawa is not extremely diverse, it has become a bit more cosmopolitan in outlook since the early 2000s.

When did you get interested in art?

I felt a great deal of isolation growing up. Not only was I an only child, but I was timid and introverted. That’s when I started to get into art, which was always this part of me where I felt I could outwardly try to connect with the world. It was also the only hobby that always felt accessible to me. It was just my little safe space when I was young, such a beautiful private world.

So, as I understand it, your art was developed in a kind of isolation.

In fact, when people came up to me about my art, it was always as if I would be speaking for myself, my own worldview. It wasn't necessarily something that I inherited from my family because I didn't have anyone around me who really understood or appreciated the visual arts. It really was just something that came to me over time. I didn't have many outlets or many other ways of expressing myself outwardly at the time. I needed to entertain and comfort myself in my own way, and I felt like art and making work, just creating these stories in my mind was a way to continue relating to the world.

Going back to culture and country, what were some of the biggest cultural norms and experiences you had growing up that really resonated with your Haitian heritage?

I think one of the biggest cultural norms that really kept me in touch would be the music. That's something that keeps me coming back to my roots even now, because as a child, I remember how my grandmother would always play music including classics from the genres of Twoubadou, zouk, and kompa at home.

What’s Twoubadou?

It’s a very slow romantic melody, which, mind you, I did not like when I was younger. But it was always there, like a backdrop to my childhood. I also remember these big parties we had, where we would rent out, for instance, a community center and then the adults would just dance the night away. This culture came directly from Haiti, where people would have these grand events and just come together from all over. I just remember us kids running in and out between the adults when they were dancing on the floor and having our own little fun. That and the music playing in my head and the nostalgia attached to it were good memories. And then just thinking of food is how I continue to be connected to Haiti—you know—the rice, beans, the soup, and the joumou. There would be a huge spread during all those festivities we do every new year.

When did your interest in Haiti take a more serious turn?

My understanding of the actual significance of events regarding our country came eleven or twelve years later, how it was geared towards celebration—the independence of the slaves, for instance. Before that, I took everything for granted but basically, I was raised in the Haitian tradition. Even just the way my hair was done, like the beads that my mom would thread into my hair was so much like the schoolgirls in Haiti. Although I feel that it's so difficult to view history when it comes to Haiti, the character of the people is still so well expressed in the music. It embodies that slow tenderness you cannot easily find anywhere else. I know many people scoff at the idea of nostalgia and tell us to move on when it comes to thinking of the country they left. When I think of Haiti, it’s important to really capture its essence. That's really what the soul of the nation is.

I had a somewhat similar experience. I grew up in Detroit, Michigan, which borders Canada. Detroit has the largest percentage of Black-identifying people of any major city in America. I grew up knowing a lot of Black Canadians, just from going across the border and families moving over to Detroit, as well. But what do you think are the similarities and differences between the black experience in Canada versus the Black experience in America?

That’s an interesting question because even thinking about Blackness in the arts and the way that it's been documented in Canada is so sparser compared to the U.S. Canada, and in the U.S. too, is such a big melting pot when it comes to Black identity. However, in the U.S. there’s a very strong Black American core, whereas in Canada there seems to be no easily definable one. The Black experience is more dissipated. Of course, with you, the African American presence has a strong and undeniable foundation within the country’s history. For Canada, the strong base comes more from the indigenous people, that is, the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. And then the Black question follows.

I know in America there's also an indigenous presence with the Native Americans. But It seems there's a lot more emphasis on the friction between African Americans and whites today than indigenous people—and that's where the attention is given for that community to be seen and be understood.

In Canada, while there's always been a fair amount of discussion around blackness, there is an important legacy of erasure because of the ‘newness’ of us being in the country. A lot of us are migrants, so most of us don't have the degree of vested interest that African-Americans have. But of course, there are also Blacks that have been in Canada for as long as African Americans have but this is confined to specific places in the country like Nova Scotia and such. They're still able to retrace the story of their ancestors in Canada. These are the aspects of our society, which make it so interesting, to see how in Canada we have so many different takes on Blackness. Whenever you meet a Black person, you don't really assume that they're going to come from the same cultural experience as you. You look like me, but I know you probably don't have all that much in common with me. You could be Jamaican, Congolese, whatever.

And that's the beauty of growing up in Canada as a Black individual, seeing how rich and diverse our cultures are. There're so many ways we can relate and learn from each other. Just the idea of unifying based on the color of our skin was something I didn't necessarily grow up with here. We all feel very different and thrive on our differences. Our experience is different than the American struggle, though it would be good to find more common ground among us.

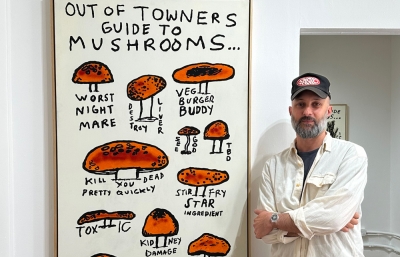

Among the subjects you’ve explored, I found this touristic notion of exoticism very fascinating. I remember you did a show addressing that subject. Tell me about that topic and why that was important in your dialogue.

Now that’s an interesting topic. This space that tourists find so exotic is also very dark. When you think of Haiti, you don't necessarily think of just the beautiful beaches. You think of the Caribbean nature of the island cluster. We're part of the Caribbean, but also outside of it because we gained our independence much earlier and had to pay a high price. I think that a lot of this touristic gaze of Haiti really stems from a deep-seated fear of Black governance. The show that Sarah-Mecca Abdourahman and I did this past summer was called Le dernier des touristes (The last of the tourist).

The tourists generally come with a mind to take from this place of pleasure, typical of most tourists. And the term “tourist” became almost a symbol for just any outsider. That could be a writer, journalist, or photographer, whoever comes into this territory. So how are they feeding off that terror or feeding off those vulnerable spaces? By perpetuating a touristic way of just thinking and just taking from these spaces. Whether writers, journalists, politicians, or international powers, they all try to do it on a large scale. So, a lot of the themes in the show had to do with interpreting that first encounter between the north and the south. That is true of the U.S. occupation or missionaries coming into Haiti and the different humanitarian missions that have occurred over time. The question is what are they really doing through this help? Is it what we really need? What's really going on behind the scenes? The list of these interventions just never ends. That was essentially what we focused on in the show, that tension between the people and their supposed “benefactors.”

Listening to you and through some of the research I've done about you, I feel that language and storytelling are personally important, not just in English and French, but also Creole. Tell me more about the importance of language and narrative for you.

It’s true, when it comes to language, it comes into play in how I consider naming my titles and sometimes I use it directly in the works. Some of them will have Creole titles, others French to accurately reflect my thoughts and emotions. But a specific language could be used to address a specific community. I also think of the importance of language when I remember the difficulties my grandmother went through without the opportunity to learn to read or write when she was young. When she came to Canada, the first thing that she did was sign up for school so she could learn just to sign her name. Think of how the mere act of signing your name gives you ownership and how writing gives you a record to be remembered by.

Histories of places are most often remembered and documented through written language, which, ironically, whole communities are denied entry due to illiteracy. And so, the records are written mainly in French or in English, but not in Creole. This often gives rise to a different perspective. In the same way, thinking of these paintings to document history makes the truth more accessible to a wider audience who don't always have access to their own history. That's also how language enables me to present my views, helping to break my thoughts down.

What would you have read historically that's helped shape the way you think about art?

One book, Silencing the Past by Michel-Rolph Trouillot introduced me to the term “historical production” and how most of what we know about the past is based on sites of struggles between power and history. It also got me thinking of how history could be considered as fictionized in the sense of asking who is the one who dictates how others are to be remembered. Not only who gets to dictate, but who gets to be remembered, and who also gets to dictate how that is going to be presented as history. And that is what led me to think of the power that paintings truly hold where they are equally capable of becoming a commentary of history. They shape our thinking of historicity as well as become an artifact for that specific moment in time they capture.

So that’s what led me to create more paintings of Haiti, with emphasis on its diaspora. There's always a continuity between the two that I feel needs to be addressed. Because as we keep moving across oceans, our history and culture are still embedded in us even though we may feel there's a gap due to distance or the progression of time. It’s therefore crucial that diasporas, especially in the western world, never lose that connection with their homeland and continue that merger of the two worlds. In this regard, I was really inspired by the thinking of Michel Rolph-Trouillotand, and that has inspired a lot of my current work.

lvurena.com // This interview was originally published in our Spring 2023 Quarterly