Lindsey Brittain Collins

Her Space Odyssey

Interview by Charles Moore // Portrait by Laura June Kirsch

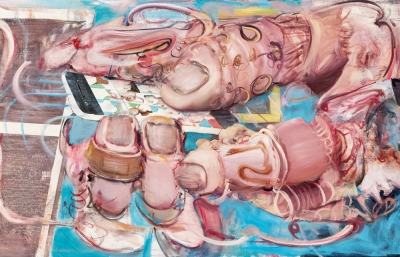

Artistically speaking, Lindsey Brittain Collins is an enigma. The New York-based painter received her MBA from Columbia University, but it was her time in business school that gave her the courage to pursue her love of art full time. Before graduation, the Virginia native enrolled in nighttime painting classes, wandering to the Parsons School of Design campus after dark, and as of today, one might say she’s come full circle. A recent MFA graduate—again at Columbia—Collins works across several mediums, from collage and sculpture to installation and other formats. Her work explores architecture (another career path she considered), economic structures, aesthetics, and more specifically, how these elements shape racial perceptions and urban environments. Confronting the erasure of Blackness and Black history, the artist has forged a path in exploring and reexamining the white gaze upon her work.

Rooted in a blend of research and spontaneity, Collins finds inspiration in the things that captivate her as she simply exists in the world. Some of her earliest work, in concepts she still revisits, is a series featuring Nannie’s Grave or the burial site of a young girl who died in Georgetown just shy of her eighth birthday in 1856. Located outside of Washington, D.C., where the artist briefly lived after earning her business degree, the burial site was once a stop on the Underground Railroad. Steeped in historical narrative, there are nonetheless gaps in our collective knowledge, as Collins explains, no last names or death records, nor any information on Nannie’s life. Yet each time Collins returns to Nannie’s Grave, she finds new offerings: dolls, toys, laminated birthday cards, and other trinkets.

To this day, the painter continues to explore Nannie’s legacy, as in the impactful Nannie’s Grave (2019), a 54 x 44-inch oil, acrylic, and cement on canvas work, where the artist depicts the child at a standstill—trapped, or perhaps suspended in space, her face at rest, eyes open and calm. Where do Black bodies come into play, Collins asks? How can a young girl about whom we know so little make such a significant impact? During quarantine, the artist made paintings of small figurines inspired by the same gravesite, and thus, a new and personal series based on the dolls left for Nannie. This same sense of intrigue guides Collins in all her work, from triptychs based on inkjet prints of her photographs—the architecturally striking Anguish Reaching into the Sky (2020), for instance—to a new and innovative series focused on Black students creating safe spaces in white institutions. Mainly based on her own experiences and that which most inspires her, Collins continues to approach the Black existence, contemporary and historical, through a critical lens. The artist’s work is research-based and emotive in equal measure, both conceptual and storied, broadly impactful in the way it sheds light on the people and places that are far too often overlooked.

Charles Moore: Tell me where you’re from.

Lindsey Brittain Collins: I was born and raised in the Washington, D.C. area and then moved to Princeton, New Jersey when I was 11. I went to undergraduate at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia, and when I graduated, I moved to New York City and have been here ever since.

What did you study at UVA?

Economics and Sociology with a minor in Latin American studies.

And then you went on to do your MBA?

Yes, I did my MBA at Columbia. I’ve always had an interest in business and was on a very different career path, but it was my time in business school that made me realize that what I was studying was just an interest and not what I wanted to do as a career.

So you decided to follow your passion.

Yeah… the thing is I've always been an artist. I've always loved art and made art, and I think being in business school gave me the courage to pursue a career as an artist. While I was in business school, after my first semester, I enrolled in painting classes at Parsons. I was balancing business school during the day and painting at night because I didn't have any formal training prior to that. I was mostly self-taught, and painting was something I was doing as a hobby. Then, after graduating from business school, I pursued art full-time.

That’s fascinating. So you graduated and went right into your MFA? Or did you take time off?

I took time off. I was making and selling art while building my portfolio. But the idea of going back to graduate school was in the back of my mind.

So what were you making in between those years at Parsons and starting your MFA?

I was actually making a lot of figurative work. I was interested in the Black body. I’ve always been interested in telling stories of Blackness and Black history, so I was making figurative and representational work up until my first semester here at Columbia. I started to think a lot about the gaze, both Black and white, in my work and what that meant for the Black bodies in my paintings.

However, as the political climate started to intensify, I found that figurative work was becoming a bit exhausting for me. There were a lot of ideas that I wanted to express but I didn’t want to put that pressure on the figure. So, I slowly started to move into abstraction

What were you making initially?

Some of my earliest work, that I’m still doing today, is the Nannie’s Grave series. After business school, I moved down to D.C. for two years. While I was there, I was doing a lot of research on the Black history of Georgetown. Georgetown has a rich Black history and was about 45% Black during the late nineteenth century. Today, Georgetown is a mostly white, very affluent neighborhood with a large focus on upscale retail.

Well, in the course of my research, I discovered a graveyard that was thought to be a stop on the underground railroad. When I visited the graveyard, I discovered a grave for a little girl named Nannie who died just shy of her eighth birthday in 1856. Her grave stood out to me because someone had left a collection of antique dolls in front of her headstone. There was something really special about her grave that drew me to it. Over the years, I’ve kept going back. Every time I visited, I would discover that a mystery visitor had left a new toy offering and a laminated birthday card for her birthday. I’ve been documenting my experience with her grave over the years ever since. So, Nannie’s Grave is the only series that I started right after business school and have continued working on to this day.

I must say, when I see work like this in your studio, I usually assume that you have some architectural history. There’s a definite meticulousness about your style akin to the discipline of architecture. Where is that coming from?

Funny you say that because, at one point, I wanted to be both an architect and an artist. But the more I learned about architecture, the more I felt that it was too rigid and structured for me. It didn’t allow the same freedom as art making. All the same, I’ve always been fascinated with architecture, design, and space. I love studying how buildings live in space, how bodies move through space, and how architecture impacts our experience in space. So I’m excited about incorporating that dimension in my work.

Great! Looking at this piece now, is this a triptych?

Yes, this is a triptych. I showed it together as one piece. It’s just not assembled as one piece right now. I wanted the panels to be rearrangeable. It’s called Anguish Reaching into the Sky.

Tell me a little bit about it.

This piece was actually inspired by a class I took while I was in business school called Social Impact Real Estate Investing, which was under the social impact arm of the business school. The professor was the managing director of a prominent investment bank, which owned a lot of property across the city. Our final assignment was to put together a residential deal for land that the bank owned in Harlem.

Since the class was a social impact class, I assumed we were going to explore ways we could make a positive impact in the community—this is what I thought the focus of the class would be. Turned out we were graded on profit maximization. Thinking about the neighborhood of Harlem, it really struck me how easy it was to reduce the residents, real people, to data points or variables in an Excel model with the goal of profit maximization as the primary objective. This was something that stuck with me. Now, being back in Harlem in this MFA program, I wanted to revisit that experience from a new perspective.

I decided to walk around and see how Harlem had changed since my business school days. I took out my camera and photographed the space, seeing whether those photographs would lead to inspiration for a painting. I developed the film which I hung on my studio wall. A composition started to emerge, and I just kept building from there. There are a lot of hidden narratives within the piece: the more time you spend with it, the more the stories will come forward. I chose to use blue tape to build the composition and hold all the pieces together to indicate that these pieces are moveable, just like puzzle pieces that can be shifted around. I also think of the blue tape as data points signifying the people within the community. Conceptually, the idea of the dehumanization of people through data has been a recurring theme in my work.

Let’s talk about the materials because, in my view, it looks like it’s more than just the tape that is fixing the pieces.

First, I build a composition. These are all inkjet prints of my photographs. I use the blue tape to hold them up as I’m moving them around, and then everything is fixed with glue followed by a layer of varnish.

Do you use a roller?

No, a paint brush. I wanted it to feel painterly and the blue tape also has the mark of my hand that gives it that painterly touch.

Tell me more about this work in progress again.

This collage painting is about how Black students are able to create safe spaces within predominantly white institutions. After reading your curatorial statement, I thought a lot about ideas of prestige, privilege, and power and how those values are reinforced through the neo-classical architecture at colleges and universities across the country.

Thinking about my own experience as a Black student in predominantly white institutions, there was a sense of non-acceptance from the white students. This piece is focused on my experience at UVA, at a time when there was a lot of racial tension on campus and in the surrounding Charlottesville community.

Every year I was at UVA, there was a racial incident, whether it was violence, or racial slurs… I can go on and on. As Black students, we were not made to feel safe in these spaces. I was reflecting on my experience at UVA, which, despite those incidents, I still regard with fondness. While I was there it almost felt like I was at a HBCU (Historically Black College or University) within a PWI (Predominately White Institution) because our community was so close-knit. I thought a lot about how in the midst of the architecture of the university, we created spaces for ourselves that contributed to that sense of community.

The piece celebrates how Black students are able to repurpose the architecture to better serve their needs as students and to create safe spaces to exist—to commune, be our authentic selves, experience joy, and display our culture. The BBS (Black Bus Stop), BET (Black Eating Time), Black parties at white fraternity and sorority houses, and the Tree House, were all examples of ways the Black students at UVA gave new function to existing architecture at the university. These memories were an important inspiration for the work.

I took the same approach with the work as I did for Anguish Reaching into the Sky. I went down to Charlottesville and photographed the university. I used those prints to build out the composition, and within the collage, I’m also embedding some ephemera and memories from my scrapbook from undergrad. Some are very positive memories from parties and funny flyers, and others are not so positive. I saved things like the news clipping from the assault of a Black student on the lawn or a list of all of the buildings and spaces that are named after white men who have a history associated with racism. So there’s a lot embedded within the collage. It’s also a reflection on personal memories, and the color choices reflect that. The spaces are both real and imaginary and are drawn from my memory of attending UVA many years ago. The very act of producing this work makes our spaces permanent and elevates the stories of Black students.

By the time this interview comes out, your thesis show will have happened. Anything else you’re working towards this winter?

I’m presently focused on my thesis. This year was very disruptive, and our schedule is really out of whack and way behind. I’m taking the time to reflect on my work from the first-year show and it’s really impacting how I’m choosing to approach my thesis. Without the traditional timeline of having a break between these major milestones, it's really accelerated the speed at which I work. I typically work pretty slowly because my work is largely research-based and very conceptual. So, it’s a change of pace for me, but it’s good because it’s pushing me.

I just presented a video at the Jewish Museum about the Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, VA, where UVA is. The work challenges the place and purpose of confederate monuments in America.

Tell me about the video.

The video was part of the “in-response” program at the Jewish museum. We had the opportunity to respond to the exhibit “We Fight to Build A Free World”, or a particular piece within the exhibit. I chose to respond to Jonathan Horowitz’s piece, which is a sculpture of the Robert E. Lee statue covered in a Black shroud. After the “Unite the Right Rally” in 2017, the city was trying to determine if they could legally take down the protected statue. As you can imagine, there were two strong opposing views. The happy medium was to cover the statue in a Black tarp until the city was able to make a decision.

My video response narrates my experience encountering the statue in Charlottesville. I expressed my reaction in a poem which is narrated over a video of text that I projected onto the statue in the gallery. This was my first time making a video, which was fun, and even though things were challenging because of Covid, the museum was amazing to work with and they let me go into the gallery when it was closed to shoot.

What was really exciting was that the day I sent the final video off to the Jewish Museum, the Supreme court ruled that the Robert E. Lee statue could be taken down. So that was a huge win and I secretly felt that even though my video hadn’t been seen by anyone else yet, it was so powerful that it magically influenced the timing and the decision. Although the statue has yet to be taken down, I’m glad these kinds of changes are starting to take place.