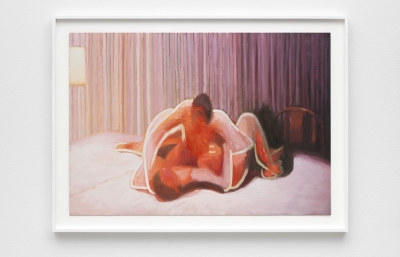

Nicolas Party

A Hug From On Top of You

Interview and portrait by Sasha Bogojev

There are many elements in Nicolas Party’s work that justify the princely position and reputation he’s built so swiftly. We could begin with a deft interpretation of classic visual imagery. From still lifes to portraits and busts, to grottos and landscapes, his prolific oeuvre is firmly rooted in traditional art. Or we can talk about the immersive experiences he has conceived and built, transcending the ubiquitous white cube into theatrical presentations. Then there is also his skilled fondness for the unfairly neglected medium that is soft pastel, all of this encompassing a wide-ranging practice of drawing, painting, sculpture, installation, ceramics, and his own brand of performance. His iconic sculptures and unique pictures can convey the venerable patina of an ancient culture or the futuristic rendering of a utopian vision of the future. His enveloping installations and presentations pack up a singular and unforgettable experience.

And while working on this feature, I realized that timelessness also came through in a conversation I had with Party in Brussels back in Nov 2019. We spoke the day after his opening of his solo show with Xavier Hufkens, and it provides a great insight in the range of serendipitous influences and experiences that framed his interests and practice.

Sasha Bogojev: I want to start with the most obvious question about the transformation of spaces. What are the roots of your fascination?

Nicolas Party: When I finished school, I had this kind of art space in Lausanne with two other friends, and we organized shows and things. We would invite people to do shows, and every few months, we would have a music-related event and build a kind of a set. We’d put different stuff on the stage, the walls would be painted, and so on. When I got to Glasgow, I kept going with those walls and when I started having shows, I was also doing a lot of murals. I think the breaking point for the physical intervention, in terms of architecture of the space, was the Karma show in New York in 2017.