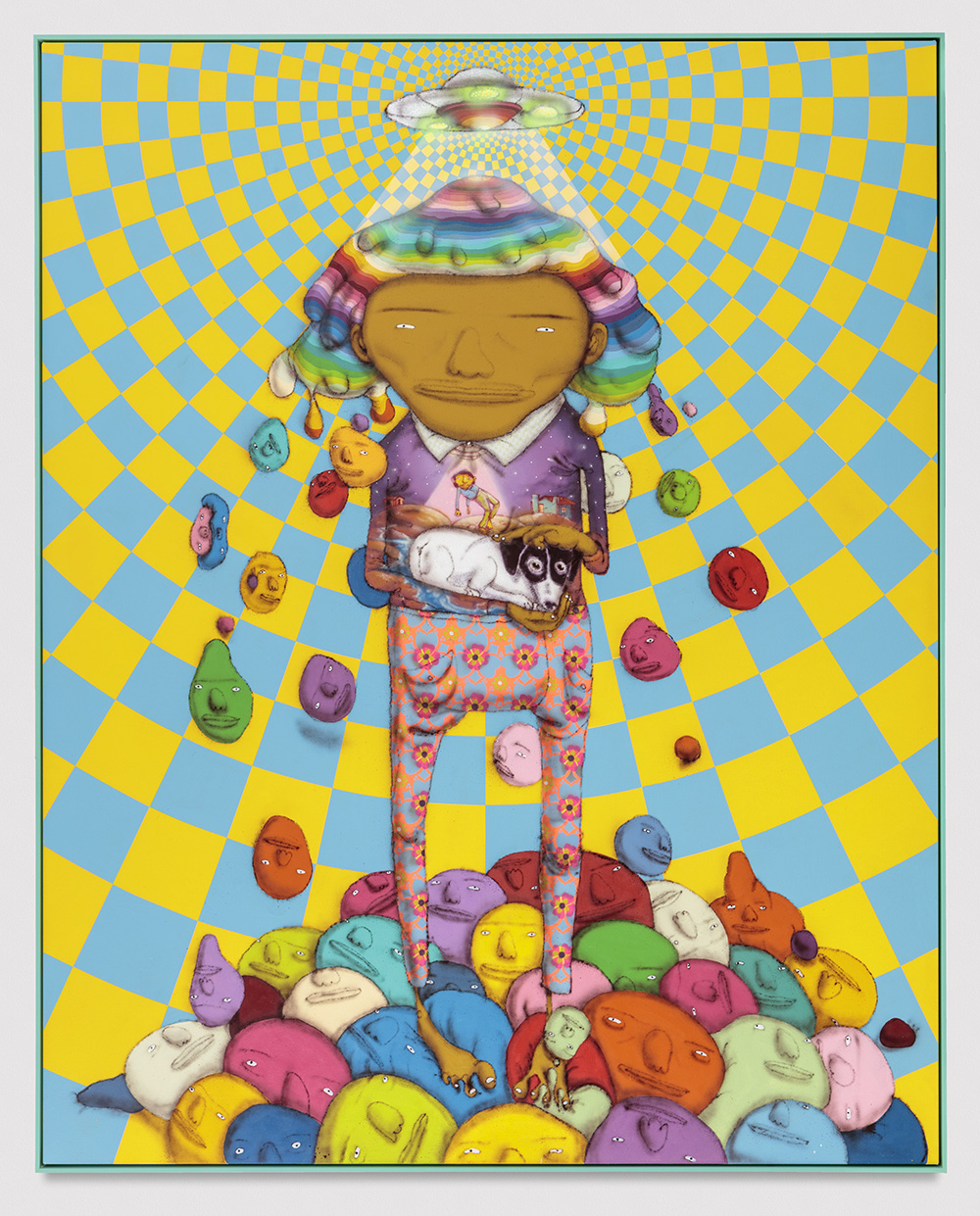

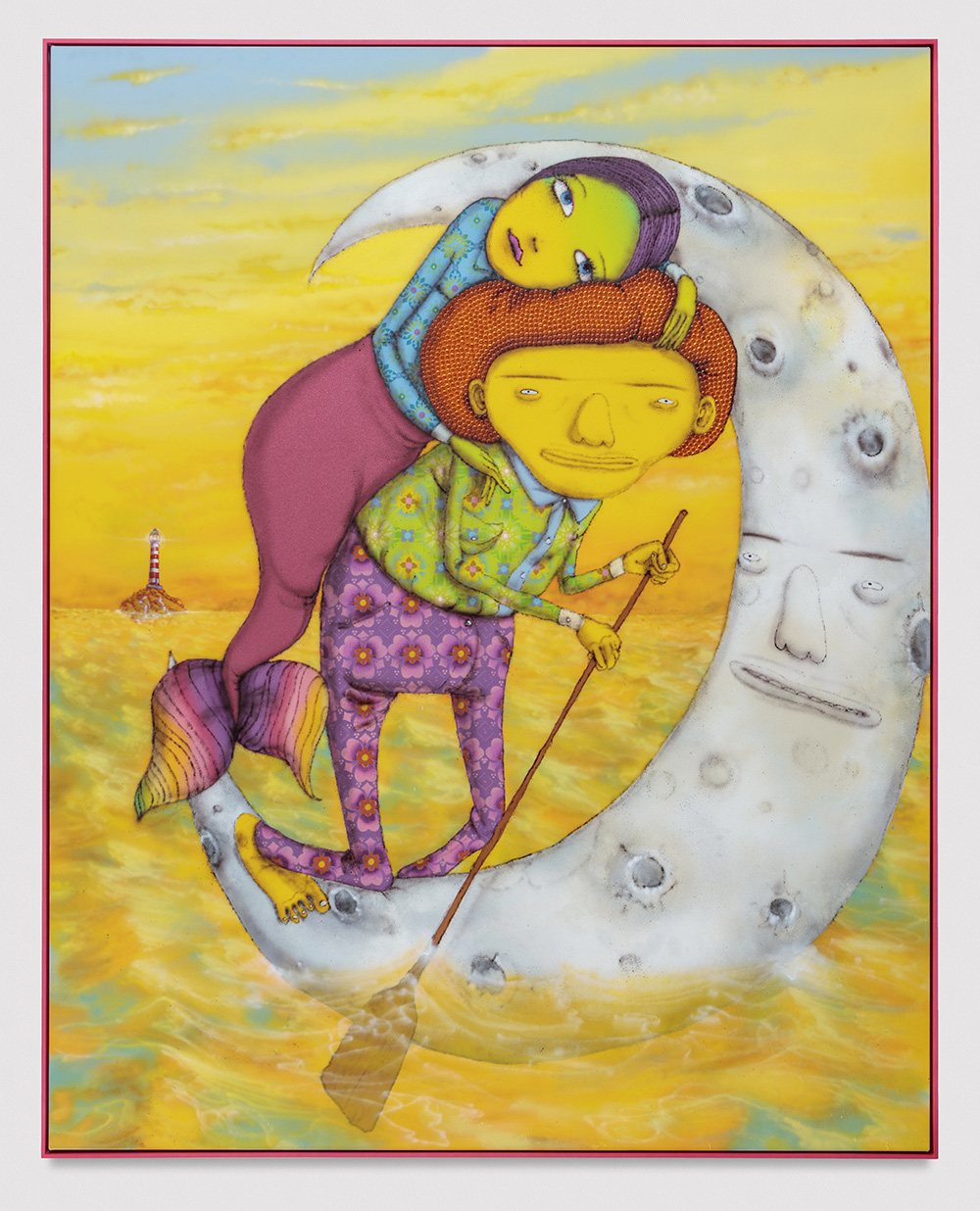

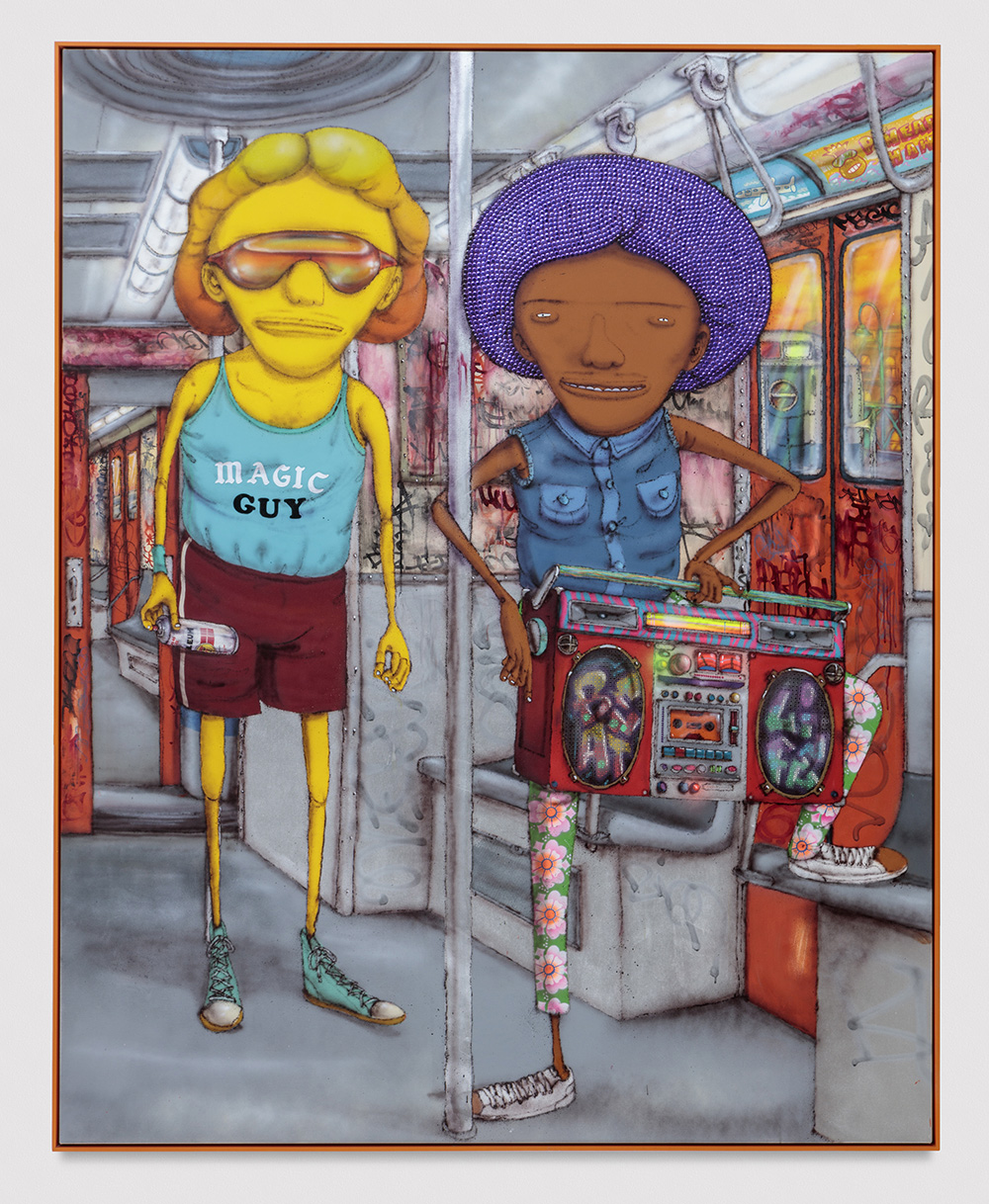

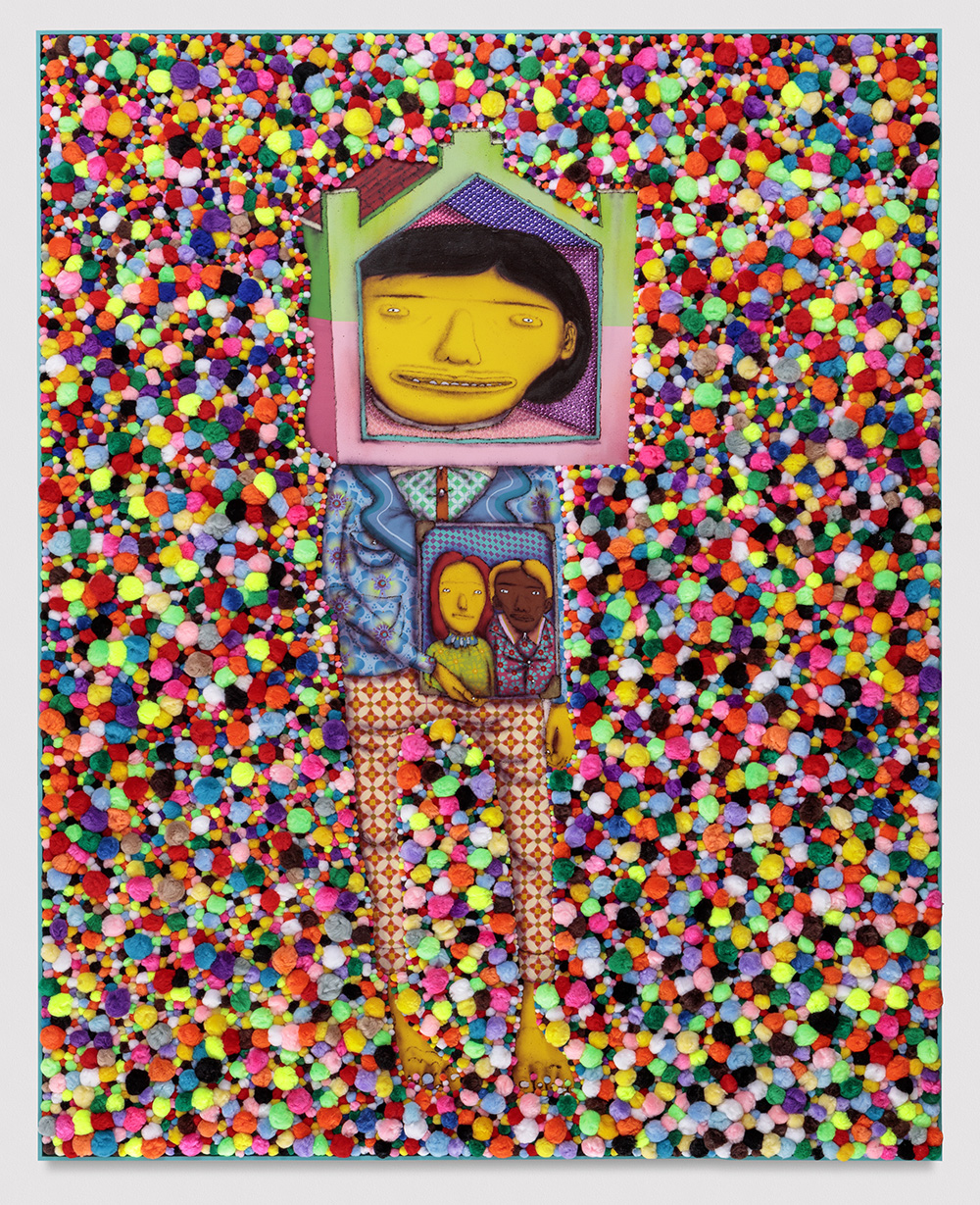

OSGEMEOS

Everyday They Write the Book

Interview by Sasha Bogojev // Portrait by Martha Cooper

Recognition and respect from the general public for something to which you've dedicated your life is probably one of the most satisfying feelings a person can experience, even sweeter when that recognition becomes global. When that happens in multiple fields, for different kinds of activities, and in this particular case, forms of creative expression, we're dealing with an extra special, almost extraterrestrial individual. Multiply that by two, and the prodigious product is Otavio and Gustavo Pandolfo, better known as OSGEMEOS.

The twin brothers, from the Cambuci district of São Paulo, are recognized among the most respected graffiti writers of all time, but are also considered pioneering forefathers of street art as we know it today. Artistically active for over a quarter of a century, they now regularly show their studio works at blue chip galleries and big art fairs like Art Basel. On top of this, OSGEMEOS have become household names in their native Brazil and synonymous with old school hip hop culture. Eight years since their work last graced our cover, we finally got a chance to sit down with the twins during the opening of their newest solo show, Déjà Vu, at Lehmann Maupin in Hong Kong and take an expansive look at their inspirational artistic career.

Sasha Bogojev: For the younger generations and those not knowing the story, could you tell us a bit about how you got introduced to hip hop culture and graffiti?

OSGEMEOS: So, we were born in Cambuci in 1974, in a very calm, Spanish and Italian family neighborhood. We grew up in the 1970s and ’80s, when everyone played in the streets. We would be staying in the streets 24 hours a day, just playing, playing, playing. At that time, there were no dangers in the streets like today, so we would be outside almost the whole day. And next door from our house was the place where all the b-boys hung out. While we were playing football or whatever, we saw these guys dancing. In time, we started to hang out with these guys. They were a bit older than us, but we thought, "Oh, I wanna do that! I wanna spin like this!" It was very natural because it was what we had in our neighborhood.

How did the breakthrough outside Brazil happen?

That was much much later. We've never imagined that one day we would be here, talking to you. Never. Because, before we were into hip hop, we already had this world that you see in our work, even before we were born. And when we were three or four years old, we started to draw everything we could imagine, just drawing, drawing, drawing. So, once we discovered hip hop, we started break dancing and doing graffiti, and later, rapping and DJing. But we never forgot these drawings that we were always doing. So it was very natural to use them with the graffiti and express ourselves like this.

If I remember correctly, Barry Mcgee was big part of your introduction to the US, right?

Yeah, but before he came to Brazil, we did everything by ourselves. The information that we had wasn't much, but we had some, like Beatstreet, the heavy Breakin' movie, Subway Art and Spraycan Art books. That was the knowledge we had, and we were exchanging it with other guys all the time, like SPETO, for example, who was very important for us. We grew up together, painted together in the city in the late 1980s in the way that we thought was correct. We would paint in the daytime, and started painting on Sunday afternoons to see what would happen with the police. And we made people understand—okay, it’s Sunday, if you see somebody spray graffiti, that's normal. Of course, we had problems sometimes, but we did a lot of walls. So when Barry arrived for his nine-month residency in São Paulo, together with Margaret Kilgallen, he had no idea what he would find. Everything was already there, back in 1994.

So how did you guys get in touch?

When he saw one of our works in the street, he looked and found us. Back then, we were living with our mother and didn't speak English, but she did, so our mother would translate everything. He just showed up at our house. Imagine that! He is the best guy, not only because of his talent, but because of his character. He is one of the best friends we have.

How did that look, what did you guys do?

He showed us for the first time how to tag, how to make throw-ups, stickers, markers. He showed us a lot of graffiti magazines and Style Wars for the first time. We still had never seen it, ten years after it was filmed. We took him bombing, but we were just learning from him, watching him tag, watching his hand style. We spent nights and nights just sitting and tagging together.

Is the friendship exclusively graffiti-focused or did you ever considering creating studio work together?

We did it a lot of times, but only for us, not for galleries or anything. Because the relationship we have with him is much more than painting. It's like we know each other maybe from another life, it’s very spiritual. He became really close with our mother, and we are like family.

What happened when he left after nine months?

When he went back to States, he started talking about our work with people in San Francisco like the the Luggage Store Gallery, and Marsea Goldberg from New Image Art in Los Angeles, and they were the first galleries we worked with in California. And later, with Jeffrey Deitch in New York, too. When Barry met Allen Benedikt from 12ozProphet, and told him he was in Brazil, they met us, and blah, blah, blah. So Allen decided to come and visit with Caleb Neelon, who wrote SONIK. They came to make an interview with us in 1997 and did a huge feature in 12ozProphet, so that was how people all over the world found out what was happening in South America—Brazil, Chile, Argentina. There was no internet or social media back then.

As a 1990’s skateboard kid, I often get sentimental about how things used to be. Do you miss the "good old days" and how things were 20 years ago?

We miss it in a way, but also, in a way we don't. We miss it, because even though we still live there, it was really, really special, that time in the 1980s. We never thought it was going to end. But we don't have photos! We didn't take photos, we didn't film, didn't have Instagram, nothing. You had to just live the moment, and that was very special. We'd go to b-boy's bench every Saturday, back in 1986-87, and it was always a special moment. We'd wait the whole week for that moment. Even these days, sometimes, we’d go paint with our friends and not take any photos, just do it for fun. It's about living the moment and not worrying about posting this, posting that.

Tell us about 12ozProphet and how that all started.

Yes, Loomit from Germany saw the article and just wanted to come and paint with us in São Paulo, together with Peter Michalski. They were the ones that said, "You guys need to come here to Europe and show us what you do!" They were the first ones to take us somewhere like that. The nice thing was that, at this time, we had the magazines from Barry. Now we saw the work from Europe and realized, "Wow! People are doing all this all over the world!" And at the same time, we were doing our thing in São Paulo, just inspired by all of it.

That is what is so amazing about graffiti, how it gets modified and appropriated in different parts of the world.

When we started going to Europe at the end of 1999 and saw how strong graffiti was in Germany, France and Holland, it was really powerful. But we brought our style there, and for everyone, it was something totally different than what they were already doing. So when we arrived, we already had our style, which was good. People could see that this was different because of where it was coming from.

Is that when you started showing at galleries?

Once we arrived in Europe, we did some shows in Germany, Portugal, and Spain, and Giorgio Dimitri from Italy contacted us to do something in New York. He then contacted Jeffrey Deitch, because he knew that he worked with Barry and that Barry already talked to him about us. They organized the exhibition for the first time in New York. Before that, we already had exhibitions at New Image Art in LA and The Luggage Store in San Francisco. We did the show with Jeffrey in 2005, and that was one of the big moments.

How does it feel to be where you are today, working and showing with galleries like Lehmann Maupin in New York or Hong Kong, especially when compared to painting graffiti?

People that do graffiti do it for themselves; it's graffiti life and we respect it very much. But for us, it was necessary to have a space to create our environment. And our shows are not graffiti. Graffiti is outside, in the streets, where nobody has to tell you how to do, where to do. You just do it. Since we started working with Lehmann Maupin, they understood how we work and give us total freedom and support to do what we like. They are very special, and the way we collaborate is really good. It's like, "The space is yours, guys, you can do whatever you want cause we believe in you." It's good when the galleries understand the artist and support them in a way that they can do whatever they want. For our NY show, we did big installations in every room, we had QBert DJ at the opening, and we dedicated one room to old school hip hop. We have felt lucky with all the galleries we worked with over the years.

To me, you feel like the "good ghost of old skool hip hop," like you're on a mission to keep the old school hip hop and graffiti people together through all the collaborations you've been doing with the likes of Doze Green, Todd James, Martha Cooper, and all. Do you feel the same way?

For us, something that is really special—we come from Brazil. We're not from the US or Europe, where there is a big graffiti scene. We have influences from the US and Europe, but also from Brazil. So we mix everything. And throughout our life, our career, we got respect from everybody, from everywhere. We learned with all those people how to deal with the scene, with the street, but also, how to experience life in a crazy place like São Paulo. I guess that can be compared to New York in the 1970s, the Bronx or something. To experience a place where you never know what's going on, it's very violent, but at the same time very happy. It made us very strong. That made us respect both the old school and new school, and especially respect where all that came from. Like the two wall murals we did last year in New York, it's a tribute for hip hop. We wanted to pay respect and preserve it, and include all these guys who were part of that history, those still here and the ones who passed away.

Is there a favorite collaboration you've done so far, or maybe even one that is your dream?

Everything has been incredible. The project we did with Slava Polunin in 2008 was really special, and painting with artists like Aryz, Doze, Barry and Todd James has been very important to us. Even the people who are famous, like Banksy, they are like our graffiti crew. We often paint together. It's about experimenting and seeing what’s going to be the result. Or the project with Pharrell and JR—Pharrell is music, but has an old school hip hop background, JR is a photographer, but has a graffiti background, and we are plastic and painting. So it was interesting to see what will come when you put music, photographs and painting together. Or like the piece we did with Banksy in NYC, which we did a long time before and without any expectations. We were just hanging at his studio, painting different things, and the piece that ended up underneath the High Line was one of them. I think art is about that, about the moment and the improvising.

What about a dream collaboration that you would like to do at some point?

Well, we could just repeat all those collaborations with all of those guys.

Speaking of dreams, how do you construct your paintings? Is there a certain work process? Are any of them inspired by your actual dreams?

They are inspired by everything. Sometimes dreams, sometimes it's things we've seen, things we like, things we don't like, messages that we need to put up.

How did the yellow characters happen in the first place?

Very natural. Yellow has been a very spiritual color for us since we started drawing. When we were drawing at our mother's house, the sun would come through the windows and the studio would become yellow. So we always found it mystical, peaceful and harmonious.

What about all the UFO or alien imagery that you include in your work? Where does all that interest in the extraterrestrial come from?

Maybe we are aliens and we don't know it. It's a fun thing for us, something we’ve had a connection with since we were kids. We'd love to get abducted one day and see it, like I see you now. It's also because of some people we've met. There are guys you meet and you go, "Man, this guy is not from here!" Really genius or really out there, just glowing. Those people are too good to be from here. But one thing that we know is that we're not alone in this universe. We like to get inspired by mysteries, by the unknown.

But you're also inspired by your family and your family roots in Lithuania. Why do you feel it’s important to portray those?

Our grandfather was from Lithuania, so we grew up listening to him talk about life there. We never had an idea that we would get on a plane and go there. So when we first had a chance to go, when our mother got invited to do a show there, it was an opportunity for all of us to go and for her to have a show and to see the country of our grandfather. She was doing embroidery and was invited by the biennial there to show her work. It was very special. Later, we discovered family still there after all the wars and everything.

I noticed that some of your street work has been very straightforward about corruption, poverty, and ecological issues in your country.

Sometimes we use the street to just talk. And we don't care what happens after. We just feel like doing it, expressing ourselves, and we don't wanna get influenced by what people say or don't say about it. When you do something in the street, it's more for people who are there. We don't believe any politicians here, or anywhere in the world.

And what about the buffing in Brazil? There was big campaign about it few years ago, I remember.

We don't care. If they buff, we're gonna paint again. They can try. People that really like to do graffiti will keep doing it. They try cleaning it, but São Paulo is different than other cities—people like graffiti. People like to see colorful walls. So when they fight against writers, they fight against a lot of people. People really enjoy driving around the city and seeing colorful walls. And this has been happening since the 1980s—painting in the daytime, graffiti everywhere.

As seen from your recent shows, including Déjà Vu, one of your key influences is obviously music. Did you have any music influences within your family?

No and yes. We grew up listening to opera and classical music with our grandfather, and our older brother was always into rock 'n' roll. He is a musician, but he never studied music, just playing for fun.

And what about the beats you're doing? There was the installation in Hong Kong with the speakers. Do you have any interest in music careers?

No, not really, because we just like to experiment. Sometimes with electro funk, sometimes disco, sometimes just house. Again, a lot of it is improvising.

You also use musical objects, like speakers, drums, but other things, too, like doors, to create work. Is that a challenge?

Not really. It’s a challenge connecting all those together, but we're not afraid to try. We don't have boundaries like that. Sometimes we feel like we need more than one life to express everything we want to. Like when you do a huge wall like the ones in New York. It's very difficult to make, and in the end, you're like, "Fuck! This was a lot of work!" But when you really want do something, you don't think about difficulties.

I heard you work really fast, too. How did you learn to do that?

Practice. More than 25 years of practice [laughs].

After all these years, you come across very motivated and inspired. What drives you to keep producing and creating so much?

I think it's because we're writing our book. Everything you see is our book. What we illustrate is our history. Every day is a new text that you need to illustrate. Sometimes it's a drawing, sometimes it’s sculpture, music, dancing, painting… everything. So we have to keep going as long as we live.

OSGEMEOS’s latest exhibition, Déjà Vu, was on view at Lehmann Maupin in Hong Kong this past spring.