Phlegm

Monuments Large and Small

Interview and portrait by Sasa Bogojev

Many artists enjoy tantalizing the media and public by playing cat-and-mouse in a practice that feels a bit indulgent, often frustrating. A few do have their simple, straightforward reasons, like engaging in illegal activities. But among such autonomos, anonymous practitioners is someone who’s among the friendliest, more approachable folks you could meet. Phlegm's choice to maintain obscurity comes from his extraordinary humility and shy natural reserve. But having a major soft spot for outsiders, nonconformists, and the lone wolves prowling about, we were determined to get him on record to talk about his practice, his work, and his resolute DIY philosophy.

I met the artist back in 2013 when he came to paint in my homeland of Croatia, and we quickly bonded over skateboarding and similar interests (seemingly) unrelated to the arts. Later on, we added parenthood and family life to the mix and have kept in touch through the years. And yet still, once we finally arranged a Facetime chat to do this interview, Phlegm… just... couldn't do it. The thought of expounding about process, about himself, is so foreign that even the suggestion of spotlight throws him off balance and renders him almost speechless. Eventually, to everyone’s absolute pleasure, we agreed to converse through the more relaxed form of email, resulting in this special conversation, one of the very few Phlegm has done over the years.

Sasha Bogojev: Your practice has gone in so many directions and you’ve done so much, how does that feel, looking back at it all?

Phlegm: It feels like I've just scratched the surface of what I want to do, really. I don’t often look back, to be honest, although lately I've been going through old memory cards to try and pull the work together to make a book of my murals. It's wild to look at how much work there is over the years.

I can only imagine! What are some of your personal highlights, your favorite pieces, projects you’ve done?

Having the chance to travel so widely has been unexpected and amazing. I feel very lucky to have been asked to paint in all these many places. To have this huge body of work, where every wall is a response and connection to the place you’re in and the people you meet, and have those experiences bonded with my work like that is something very unique to painting public space.

You’ve been putting a lot of focus on interacting with the environment and existing elements in your murals. What drives you to work in that way?

I’ve always felt a painting on a wall reflects a direct relationship with the architecture and the environment. Anything else just feels aggressively placed, like advertising. It has always been important to me to make sure the work is in some sort of harmony with where it is. I want it to be powerful but not scream, “Look at me.” It should have the same energy and scale as the building. The same applies with installation, but it’s more about the volume of space between you and the architecture, I think. It feels less harnessed to the surface, though maybe that’s because an installation is so temporary.

In addition to all the walls, Mausoleum of Giants was a pretty impressive undertaking. How did it feel to see the city where you grew up in respond so well?

It's hard to describe how it felt. I still can’t really believe it. After so many months of hard work in an abandoned factory, to open the doors to crowds like that was astonishing—heightened, I think, because I'd spent so much time alone in a damp freezing cold space with such a small tight crew of friends making it in secret.

I think we ended up with over 12 thousand visitors. I finished by spending the last of the budget buying sweets to give out for the people in the queue each day and chalks for the kids to draw on the floors. The camaraderie in the queue was so heartwarming, and people's responses were so emotional and personal. Or maybe it's just because they got out of that queue! I think I’d have cried too.

Do you have any regrets about your past work or missed opportunities, and if you do, how do you deal with those feelings?

No, I don't have any regrets. I'm exactly where I want to be. Some days I feel I shouldn’t have been so strict with keeping the galleries and art world at arm’s length, saying no to so many opportunities or wondering if I should have played the game a bit more. But that’s like wishing you were a different person. It’s pointless. I know I had to do it like that to maintain sanity and keep the control and privacy I like.

Yeah, I was gonna ask about that. But first, I wonder what drives you to constantly change technique, medium, scale? Does working in that way ever get confusing or stressful?

I'm always following the points in my work where I feel the learning curve is the steepest, I guess. That often means some uncomfortable work or some real study. I really thrive on immersive research on a subject or skill. If my brain attaches to something, I keep thinking about it day and night.

Also, although it often looks like I'm jumping around in scale or in projects, in general, I’m really never jumping around. There's almost always a plate in the studio I'm slowly engraving, even while I'm doing big walls. There’s always a natural relationship between the things I do. Working on my books and stories helps keep the narrative fresh in my mural work. Copper engraving trains you to work really flawlessly with your line work. I find when I go to painting walls, I carry some of this rhythm with me, and I can work with more confidence. Also, the hours spent engraving are grueling, so breaking it up with time outdoors painting prevents me from turning into some sort of hunched-over hermit living in a dark shed.

I feel like scale has always fascinated you.

I think my focus has always been heavy detail whatever the scale. Large scale, to an extent, frees you up so the movements are more physical and open. The smaller engraving work is really about maintaining a high level of concentration that's more like meditation than anything else. My smaller work is mostly focused on being viewed in the books I make, so I rarely think about the scale in between book size and mural size.

Hypothetically, if you had to stick to one thing, what would that be and why?

Partly engraving because I would really love to have a big body of engraved work to my name, and it takes a lifetime to do that. I don’t think a lot of people realize just how many months of work go into a copper plate. Time works like it did 400 years ago. I struggle to find a way to document it on Instagram without boring my followers’ teeth out. But yeah, if I had to do one thing, I’d likely engrave, because I feel there's so much scope there for me and it really devours time.

When did engravings enter your life and how did they become such a big part of what you do?

I’ve done engraving and etching in copper long before I worked under the name Phlegm. Engraving has mostly been in private until the last three years because I wasn't very good at it. About four years ago, I decided to knuckle down and really practice every day. I got very swept away.

I know you could nerd out about this for the entire interview, but what are some of the most impressive aspects of it that fascinate you?

It’s all about 16th century copper engraving for me. You look at a finely cut copper plate by Albrecht Durer like Death, The Knight and The Devil, or Melancholia, and it's as alive as any painting. The level of detail and the depth of tone are really breathtaking. Lines cut with a burin differ from lines using acids as for etchings. You get this sharp quality to the line. My obsession really took off when I started seeking out the originals in museums to look at in person. Something about that history preserved in print really fits with some of the things that drive my work too. In seeing them in person, you appreciate how textured they are. Intaglio prints are essentially embossed. The press forces the paper into the line, so deeper and darker cuts achieve heft and boldness, which are often lost when you just look at them in books.

It must’ve felt like a milestone to see your work alongside such examples when you took part in The World of Bruegel in Black and White at the KBR in Brussels!

It was an immense privilege to get asked to do that. It also came at a time when I was really starting to try and step up the intricacy of my engraving. Getting to see a copper plate of mine hung alongside the entire printed works of Breugel was something else.

The mural was something we kept working on, trying to make happen, but there were so many hurdles. Then, suddenly, right at the end, it all came together! I’d spent a pretty solid three months in a dark shed engraving every day, so to suddenly be outside in the middle of Brussels, painting the side of the royal library was bizarre.

When you’re making your own engravings, what are some of the elements you find challenging?

There's far more at stake when you mess up. A little slip with the burin while working on a densely cross-hatched area can mean days of work to fix.

How do you even fix that?

It’s more a case of you don’t mess up. It’s also a case of getting good at hiding it! You have to work in a calm, focused state. You get good at checking yourself. If I can’t get in the headspace, then I won’t work on a plate. Small mistakes do happen sometimes. The area can be carefully flattened out with a burnisher. So, when working on very fine engravings, it's never totally perfect.

Another challenge is that it's not as clear as working on a drawing. You cut into a bright copper, so it's often partly reliant on feeling as much as sight. You feel the line through being familiar with the angle of the tool and the resistance it has in the metal. The lines you cut can be seen as dark if you have light hitting the plate at a certain angle to create shadow in the cut. So, on top of all this, you never get a clear picture of how the work is looking unless you do a progress print to check. You can get a vague idea by just rubbing boot polish over the plate as you work, but it's obviously not as clear as when you work on a drawing on paper.

Obviously the technical aspect of your work is very important. At which point does the content come into the picture?

I think the technical aspect in artwork I admire is what makes me open to its meaning. There is something beautiful in seeing someone's time frozen in something like that. You can feel an artist's commitment to what they are trying to express.

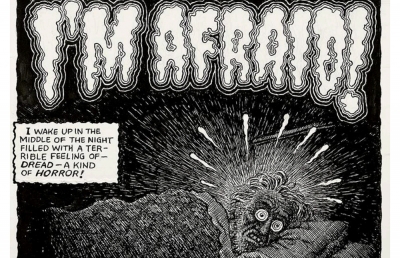

I process everything through drawing. Maybe I'm too shy or I can’t access the right part of my brain when I speak, but I really don’t feel so comfortable connecting with people. I don’t at all mean that to sound bleak. I just think that drawing has always been a part of how my brain breaks down its thoughts, much like the brain does with dreams. I don’t sit down in the studio with the belief that I'm about to create a profound masterpiece; in the same way I don’t expect every word that comes from my mouth to be deep and meaningful. Some months my work is heavy with worry and anxiety, other times it's reflective. Other times it's just playful or relaxed or stupid...either way, I'm still drawing each day.

In general, how would you describe what your work is about? Do you have a particular message, emotion or story you want to convey?

I don’t think I have any fixed theme I'm consistently drawn to. But, looking back, I can see I often gravitate to certain things. I like to use the detail and density of my work to force people to look for a long time and notice details on repeat views. Or it’s just a matter of pushing people to look closer at something, like complex machines that have a simple job. I'm interested in all the tiny, moving parts that make a thing happen, as well as the possible multiple narratives.

I like the idea of my work being a poetic parallel world to ours. Or even just a version of our world that is displaced and warped. I try to displace time in my imagery, make something seem old but then also keep parts either from our present or a slight fantasy. So it's partly a product of my imagination but also a digested and chewed up version of what I see in our world. I'm careful not to go full Tolkien. I enjoy fully visualising details of a world but like to keep it fluid. I'm not set on drawing maps and writing ballads.

Part of my process with ideas is to storyboard short stories in my sketchbook and imagine a sequence of events, rather than just trying to focus on a single image. That way, when I use an image from that story, it's part of an untold narrative. You can guess at it, but it's only ever a small part of a picture. I feel it helps me come up with something that feels real, or it distracts me from the pressure of making an image that just looks cool. Obviously I do want it to look good but that often feels like a shallow starting point.

Did these themes evolve over time, especially with the big changes in your personal and family life?

I think, before having children, I was more interested in the complexity of history and world events. Since having children, I can see a turn to more personal complexities and relationships in my work. Looking back, a lot of it looks far more industrious and impersonal than I intended. So yeah, having kids has made me soft.

How do you feel about mixing your real, family self with you as Phlegm the artist?

I’ve always wanted my work to be honest, even if I don't directly share my life. I think because it's all refracted through a different lens and mixed up, it's never too direct. I think so much just gets into the work fairly unconsciously too. Now I can look back at a lot of the creatures in my work and realise most of them slowly became bigger and rounder as my partner was pregnant. You just suck all the information in around you like a sponge and it gets mixed together. Everything from anxiety about becoming a parent, to books I'm reading on the English Reformation or evolution all just get mixed up together.

You’ve been notoriously relying on DIY ways of doing things with a few exceptions. Was this ever a conscious decision, or did it just happen this way?

I'm introverted, shy and extremely reluctant to stand up and say I'm an artist. This interview is one of a handful I’ve done over the past 15 years. I only seem to thrive in some sort of bubble. DIY has always let me put work out but not really be forced to stand by it. First, it was self-publishing books, and later it was painting walls. Both of these activities allowed me to just work and not experience much of the art world. You just do it, then walk away.

As you’ve mentioned earlier, galleries and/or agents have approached you to “help out” with your work. What prevented you from accepting those proposals?

I’ve had a lot of offers but I think my path was set fairly early. I forged a really good following for my zines when I started out, and that carried through into my print work. I've always wanted to be judged by the quality of the work I do, rather than the status of the gallery I work for, or who I'm involved with and companies I've worked for. I also think having this DIY ethos with everything I do helps me keep things personal and prevents me from getting swallowed up. Even when I get books commercially printed, I tend to hand-emboss or print an element of it myself. I like my hand to always be part of the process, partly because I want that connection to people who buy my work, and also I feel strongly about only producing what I can personally handle. Our society seems addicted to the idea of growth. I'm interested in artistic growth, but I have no desire to become bigger, have assistants, produce more. I don’t believe that’s success at all.

Yeah, the question of being a successful artist… What does it entail for you?

I honestly don’t really know. I’ve spent so long distancing myself from it all, so I can't tell. I feel very honored that I have a following big enough to support me enough so I can get lost in my work all these years. I think becoming a successful artist happens in two stages. You start to produce work that's focused and driven. It communicates something to people and they become drawn to it. I think this side of art is the real function of art in society, and it's where the real beauty is. When I'm passionate about a body of work and I can feel people really engaging and responding to it is when I feel the most successful.

But then follows monetary value, and as your status grows, you create a gravity that seems to envelop all those other more subtle elements. I certainly experienced this in my life and I recoiled from it, wanting your work to resonate with everyone when only a tiny handful can afford to have it, for example. Even when most of your work is free in the street, it feels off. You create this power imbalance between you and the audience. I want to connect to people with my work, not put myself on a pedestal.

After all these years, you’re still just being Phlegm, not too keen on being in front of the camera, behind the microphone, or known by your real name.

I like to be private, and frankly, I've never felt comfortable being called an artist. It all makes me feel awkward and anxious. The more I have to mix with it, the more it gets in the way of me being productive. I think the world has a preoccupation with celebrity, and status, and monetary value. These things feel like clumsy byproducts of something far more beautiful about art that a lot of people miss completely. I try to maintain a work life where I don't have to see any of that.

With a lot of the old sixteenth-century engravers I study, all you learn about them is a name, a birth register and a death register. What’s left is this incredibly beautiful body of work that reflects who they were in the most subtle way.

@phlegm_art