rafa esparza

A Sense of Generosity

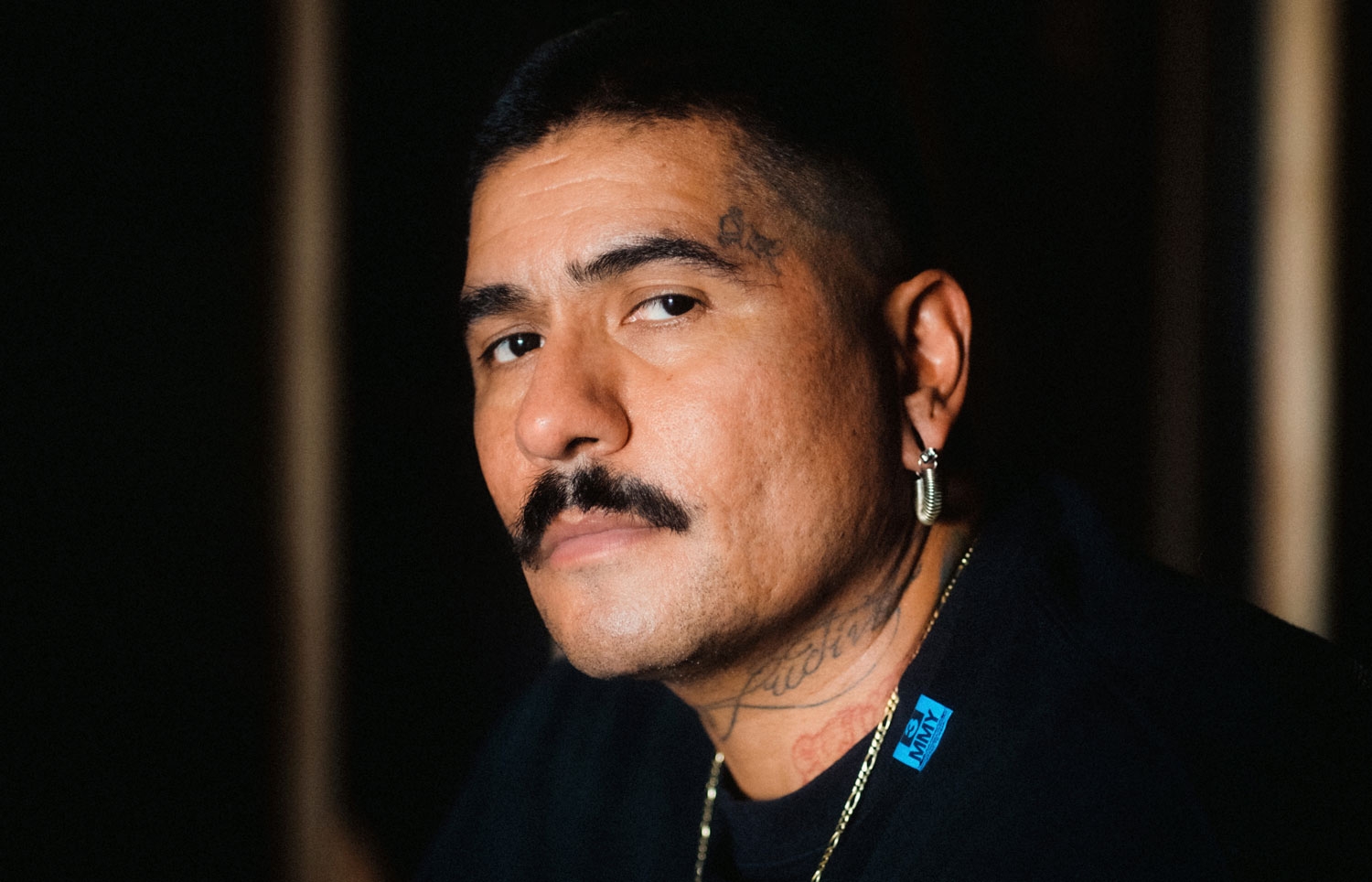

Interview by Shaquille Heath // Portrait by Max Knight

Something I couldn’t stop thinking about from my conversation with rafa esparza is that art is truly healing. Sometimes it's hard to evaluate and measure the impact. There is no real data on the visualization of artworks, no analytics to decipher or figures to calculate that explain or reason significance. Art is entirely about how it makes people feel—or, at least, it should be. All of the other numbers we attach to it—price lists and auctions, acquisitions and exhibitions—are only indicators of the fact that it made someone, somewhere, feel something. Esparza’s art feels like the essence of this notion. Before anything else, his sense of feeling is what drives his practice. It is why he has numerous group exhibitions—to share in the delight of art making with others. It is why his artworks are often a collaborative process that brings in his community of family and friends. It is why his practice explores themes like loss and love, power and pride—some of the most vigorous concepts that imbue immense emotion. Often, as esparza went on to share with me, these conversations start with a sense of generosity. And to be particularly clear, generosity is different from kindness. It is not just being considerate of feelings that does the healing, but the extension thereof. What is good for one may not be good for all. But what is good for all is always good. And that is a hella good feeling.

Shaquille Heath: I always like to hear artists talk about their work in their own words. May I ask that of you?

rafa esparza: Sure! I work across different mediums and modes. predominantly performance, sculpture and painting. But I guess my work is very grounded in conversations that deal with histories of colonial violence and all of the resulting genealogies. So, considering the present, myself, and the spaces that I frequent as a direct outcome to these histories that precede us.

I came into contemporary art making through performance art, using my body as a vehicle to produce experiences that could be viewed by communities that informed my work. I seek to allow the work to exist outside of traditional art spaces like museums and galleries and white cubes, in favor of alleyways, public parks, and sidewalks, literally in the places that I feel need to be seen and are important to those communities

But I also have a strong relationship to tactile processes. Materiality is also an important aspect of how I consider what to make. Whether it's building a concrete column that I'm going to break away from or thousands of bricks that are going to create this adobe rotunda that I invite other artists to participate in, material is an important interest of mine that really helps me materialize some ideas. I’d say adobe is a specific material that's really at the forefront of what I've been making within the last 10 years. It's a mud building material indigenous to this continent and to many arid areas around the globe. My father was an adobe brick maker in Mexico before he came up to the States, and I inherited this way of working with mud through him. And yeah, that practice has evolved from literally building blocks that were used to build brown spaces in traditional art spaces to help platform the works of some of my peers and good friends. That material has now evolved into a more intimate practice of painting, and so I've been bringing that material to the studio to literally build up surfaces that could be my canvas to paint portraits.

The adobe brick making that you inherited from your father—was that something that you learned through watching him, or was that something you asked him to teach you?

When I think about inheritance, I think there are these passive ways of inheriting things that we probably don't have so much say in or can’t help but learn. But I was very active in inheriting this. I asked my father to teach me how to make bricks, and it was a way for me to kind of reconnect and rekindle a friendship with him after having had a severed relationship due to me coming out to my family and my community. It was kind of a way to bridge that gap. So he taught me back in 2008, when I was still an art student at UCLA. It was a very intimate and personal ask for me. I wasn't really thinking about using it to make art. I just knew that adobe had a special place in his own personal history, and I thought it could be a good way to start having conversations about some guidance that I needed at the time as a young person coming into adulthood. What it did, in fact, was allow us to share space without being at each other's necks, while he passed down this way of working with land.

Did your father, your family and community support your journey to become an artist?

They have actually always been supportive of that. From very early on. I credit and appreciate all of the creativity that women in my family held, specifically in the kitchen when we're preparing for any kind of celebration, whether it was a birthday party, a baptism, a wedding, or a quinceaera. There's always tons of materials, hot glue, and a lot of craft supplies that the woman in my family would use to create keepsakes for people who would attend these parties. And so from very early on, this relationship to making, whether it was through more formal art activities like drawing and painting or to what I consider craft and sculpture, was always something that was really present in my family. They were very informal, maybe outsider kinds of ways, but forms that a bona fide art community might not consider art.

I love the idea of you going back to your father, utilizing this activity that he already supported in you, and creating something together. What did he think of the final project when he saw it?

I grew up in East Pasadena, and he still lives in the childhood home where I grew up. In retrospect, it was very special to be in his home making these building blocks that, when he was a teenager, were used to build houses. This is a very common practice in Mexico, where he comes from. In that afternoon, I think we didn't really speak at all outside of the task at hand, like him literally telling me what the ingredients are in this recipe that he learned from his elders in Mexico. But I did see it as a first step in mending our friendship. Fast forward to 2014, and I asked him to lead the production of enough adobe bricks that would be used for a massive outdoor sculpture. We made, like, 1,400 adobe bricks using water from the LA River, and they were all sunbaked. We worked during the summer. And I think in those moments were all of the questions and conversations that I was hoping to have in 2008, just very candidly coming up in conversation when we were working. My father's since become an integral part of a lot of these adobe constructions, whether they were massive scale installations or here in LA.

I also come from a family where we don't necessarily experience things, process them, and then talk about them. They don't happen in that order. And sometimes a response or reflection on an experience takes years. And so in 2017, I was invited to participate in the Whitney Biennial, and I invited my father to be there to install the adobe installation that we built. That was a very important moment in our relationship and our friendship, though by then we were already really great friends. But I think it was the first time that I heard him vocalize his astonishment for material that has arrived to me, to my practice, and to this country via his immigrant labor—and now seeing it in one of the most important museums of art in the country. It was something just hearing him vocalize, saying that he never believed he would ever see these bricks take form in his life again, and in this manner. It was also important for him to be witness to not only the physical labor of building this kind of installation, but that I had invited a whole cohort of brown artists from Los Angeles to participate in the biennial with me with their own works. So witnessing us literally build up this discursive space and be speaking to one another and each other's works.

And then there was also speaking with curators and art handlers, the team at the Whitney, and various journalists that were coming in to learn about the installation. He got to witness for the very first time a labor that, in his mind, was always very abstract. He always said, “I don't understand how art is work” and “How do you make a living from this?” Education wasn’t even something that my family prioritized in our upbringing. Labor and work were, and continue to be, very valued things. So that completely transformed his relationship to my artmaking. There was an intimate level of understanding and a new gained sense of respect for not only the artwork but, I think, also for his own labor, right? Being able to value these bricks beyond a means of survival.

There is definitely a lot of physicality in your work, and that’s really beautiful, whether, as you say, it’s building these bricks by hand or even being the performance artist that you are. Going back to what you're saying about immigrant labor (though I guess all artists work with their hands?), you can really feel that and the intentionality in your work.

Firstly, I really appreciate that those things feel palpable to you. Yes, there are things that I feel are important to be very explicit about. It's important in the way that I learn and build relationships with things by being in close proximity to the materials, places, and people. It's why I am such a tactile based maker. I need to be directly involved with materials, images, people, and places, but often these are just born out of experiments. Sometimes these works that happen once are left, and then they resurface through memory. So having had the experience of dedicating 10 years of my practice to performance art requires being able to be responsive and open to improvising. When I’m working in performance, I don’t prioritize documenting the performance through video or photo. For me, prioritizing the live audience is the focus of the work. You're creating an experience that people are immersed in, and you have only your memory to go back to that moment to describe it, to relive it, to analyze it, and to break it down. Whereas, when you have a painting or a sculpture, there is a physical object that you can always come back to and look at. I bring this up because my relationship to ephemeral work has informed how I work in my adobe projects and the images that I make.

You've mentioned all of the different people and collaborations with artists that you've worked on many times, like having multiple group shows up right now, for example, At the Edge of the Sun at Jeffrey Deitch, which includes you and 11 other artists. I love that collaboration is such an important part of your practice. What is it that you love so much when working with other artists?

So many things! I feel like very early on, when I didn’t even really have a language to articulate what working with another person creatively entailed and what that would generate, there was this sense of possibility. There was this sense of wanting to get to know someone, and maybe because of a lot of social anxieties that I have, collaboration was in some way about maybe befriending someone, haha—but always at the center of these invitations or prompts was honoring the artist, their ideas, and aspects of the work that very much inspire me and that I respect. I love that aspect. It’s a layered mode of acknowledging through lines what we’re putting forth through our work, and it’s also beginning to draw out the discursive space between projects, questions, and creative inquiries that some of my peers and I are undertaking in our respective practices. Also, because we're working together, I think, in some instances more than others, it’s being able to get to know them in a more intimate way. There's been opportunities where I've been able to bring people into a kind of residency and be able to share living space with my peers for weeks or months at a time, creating kind of an art camp type of situation. And you know, there's projects like Guadalupe Rosales that Mario Ayala and I made for SFMOMA, which was something that we worked on for an entire year! So dedicating our time to checking in every week to build this exhibition also changes your relationship as intimacy and camaraderie grow. You're able to understand and speak the same language.

Something that's very powerful to me is this mode of collaboration that opens up so much possibility. I think it really decenters these kinds of antiquated notions of authorship and ownership, right? Like, “The single artist is championed for their genius!” When we're all really byproducts of each other's ideas and environments, allowing yourself to say yes when coming into these conversations is like seeing where that takes you, even if it's scary to trust someone else's path of getting from one place to the other. Those things really excite me. I like the experimental aspect of working with other people, which has always been very interesting to me. But when you do that, collectively, in an institution like the Whitney, in an art space like Ballroom Marfa, or in a commercial gallery like Jeffrey Deitch, there's like a power, which I know is such a fraught term. But, there is something very empowering about taking up space in institutions and spaces where we haven't historically been afforded. It’s being able to be decision makers in the politics that inform how the work is going to be generated, how the layout is going to be designed, and how our works are going to engage with one another. Oftentimes, when you're invited to a group show, you don't even get to meet the other artists. So it's a very, very different way of working when you collaborate on an exhibition with your peers. And sometimes those peers, when they're your friends, there’s like this candor, and I feel like that sometimes comes through. I feel like some people really see that; it's palpable, and it resonates with them.

Oh, absolutely! I just moved from the Bay Area, and I remember the SFMOMA show, it was all over my Instagram. I remember thinking of how there is this hypermasculinity within the culture and themes that you explore, from lowrider culture to the “American” cowboy; but the thing I love is that you're so good at infusing the work with— I don't want to say softness—but a tenderness. Like the adobe bricks, right? That's a hard thing to break down and crack into. Where do you begin, and what is your thought process as an artist?

I guess one of the things that I feel most marked by growing up in the states and Los Angeles is being a big brown person, as a masculine presenting person who comes with some privileges and also some disadvantages. I understood at a very young age how profiling works, who profiles, how my body is identifiable in public space, and how that sometimes can produce fear in some people. I think I've always been hyper aware of those things. And I'm sensitive to them. You know, I'm sensitive to what my presence does to women in public space. It produces this kind of sensitivity that I'm always aware of. I remember having a conversation with my youngest brother when he was still 18 and had dropped out of high school. I would make fun of him because he would wear this backpack when he'd be out on the street, and I would tease because we knew that he wasn't in school. But he told me that he wore a backpack because he felt like it would disarm whatever projections the police would push on him. That really struck me because I still would carry my UCLA student ID in front of my California driver's license so that when I got randomly pulled over, they would see that before my ID and any notions of me being a criminal, or what have you.

So when it comes to working with my peers, I guess I always want to step into those conversations with a sense of generosity. And I want to make beautiful work. But I think what's more important, or as important, is for everyone to have a good experience. For everyone to have a memorable experience. Because I think when we're collaborating, we're afforded this opportunity to model things and do things differently, right? Being able to work outside of these kinds of hierarchies that inform traditional art spaces in the art industry is important, including being able to work horizontally with everyone. Sometimes I have conversations with artists I work with about how we can distribute responsibility within the project. I remember early on the way that projects were referred to, like “rafa with,” and then the collaborators were named. More recently, I'm like, “No, it doesn't have to be “rafa and.” If we're going to do this together and we're all going to take on similar responsibilities, how do we access the agency to be able to tell the curators: This is how our project is going to be,this is how we want to be received, and this is how we want it to be talked about? So yeah, I am unlearning and doing my best to undo some of the harmful trauma that patriarchy has done to all people in my life, men, women, and everyone beyond the gender binary.

rafa was part of At the Edge of the Sun, a group exhibition at Jeffrey Deitch Gallery in Los Angeles this past spring. rafa will also feature in I’d Love to See You at Rusha & Co in Los Angeles opening on June 29, 2024. Follow rafa at @elrafaesparza // This interview was originally published in our SUMMER 2024 Quarterly