REVOK

A SECOND CHILDHOOD

As told to Roger Gastman // Portrait by Azim Ohm

I have done graffiti for 28 years and have mostly accomplished what I wanted to do. When I started stealing spray paint from Ace Hardware and climbing out the window after my folks were asleep at 13, it was never my goal to someday be a “street artist.” I painted graffiti for graffiti’s sake, and although that experience has led me to my current place, making art is about making art.

I do, to this day, feel very trapped and stigmatized by being recognized first as a graffiti writer. I know I don’t help myself by continuing to use my graffiti name as my identity. With my current work, however, what I’m doing is making art. I don’t embrace the label “street artist,” as I think the current work I am engaged in, while undeniably very much informed by that history, is much more open and broad in its scope.

Growing up, I never considered making art or even knew it was possible. I was raised mostly in the Inland Empire area of Southern California in a very suburban, working-class family. Nobody in my family had any art education or even went to college, for that matter. Art was something that was sneered at—it wasn’t something that was celebrated or that anybody took a genuine interest in. My idea of art was album covers, skateboard graphics and comic books.

Years later, when I met and formed a bond with a lot of my longtime friends, particularly SABER, RETNA and REYES, those guys were very much interested in art. When I moved with SABER to San Francisco, he went to art school. He would talk about it with me and share his ideas, but at that time it just wasn’t on my agenda.

The first time I ever set foot in a museum was when Barry McGee was having a show at the de Young in San Francisco in the late ’90s. I liked McGee’s graffiti (TWIST) and I knew he did some kind of art practice, but I was completely ignorant about what that was, although curious. The idea that a graffiti writer was in this sacred institutional place of a museum perplexed me. I was absolutely blown away.

I didn’t understand it, but I recognized elements of how he took parts of the language he developed in the street and expanded on those ideas without it being bound to that small framework. From that point forward I started paying more attention to art, but it still wasn’t something I pursued. I was too busy writing graffiti.

Around the mid-2000s, I started questioning myself: “Why am I still doing this? What’s the point?” I was constantly trying to find new ways to keep my graffiti interesting and continue evolving but, at a certain point, it started feeling redundant and boring.

I had designed my life over the years in a way where I could prioritize painting graffiti all the time. For years and years, I was basically a full-time career criminal, and as a result, I was getting exhausted with all of the constant stress and anxiety, not to mention constant legal drama.

On top of that, I basically did everything to paint this graffiti and none of it existed anymore, other than in photos. It’s all gone—what, really, is the point? For the first time in my life, I wanted to make things that were going to outlive me. I suppose that motivation comes from the same hyper-egocentric drive to be somebody, parallel to graffiti, or more accurately, a hyper-insecurity and desire to be something and prove myself.

So, around 2009, I finally started to play with some new ideas, and suddenly, painting graffiti wasn’t the priority it had always been. Up until that point, working small scale in the safety of a studio felt like dental work, but, suddenly, I was enjoying it. I started thinking less in terms of what I do and instead more in the broader context of a “we” perspective.

Coincidentally, around this time, a string of graffiti cases I had in Australia and Coachella led to a long-overdue serious graffiti case in LA. I was in my boxers, handcuffed in my pad, listening to the head of the LA task force tell me he knew he probably couldn’t convict me, but promised he was going to bankrupt me and put me out of business. At this time, I had also been doing a lot of commercial design work for a few years and was really getting burnt out on that stuff. I knew it was time to leave LA again, so I flew to Detroit to meet my buddy NEKST and check out the city. I ended up getting a pad there and came back to LA to pack up my shit. All of this was happening as I was wrapping up my installation at MOCA for the Art in the Streets show. I expected the sheriffs to arrest me at the opening, but instead, they waited until I was at LAX a few days later, boarding a flight to Dublin.

I ended up spending two months in county jail in Los Angeles, and it was honestly the best thing for me. During that time, I planned the whole new body of work I was going to do in Detroit in my head. Being there alone with just my thoughts was liberating—no phone, email, friends or nonsense to distract me. I was able to be still in silence and ask myself a lot of questions I hadn’t asked before.

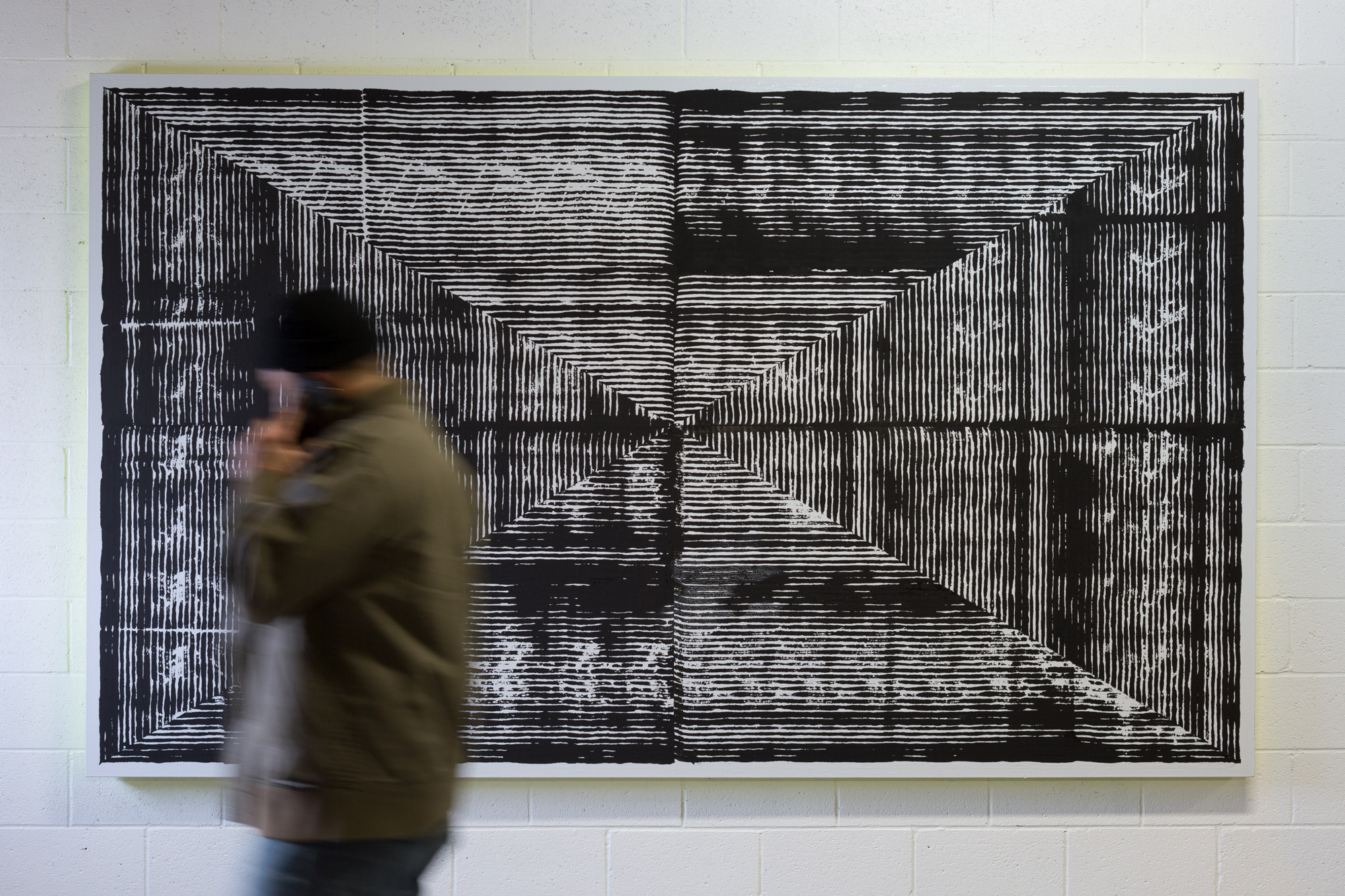

When I got out and finally moved to Detroit in 2011, my sole agenda was to figure out how to realize these new ideas. I didn’t want to do gestural painting at all, because I knew that the moment I started making marks with my hand, it would resemble all the years of the graffiti I’d done in the street. Part of it was designed to destroy my ego and remove that comfortable, familiar way of making and creating. I had to engage in a restricted process to remove my hand out of the equation.

A lot of what I was seeing from my peers felt like they were trying to figure out how to do what they did in the street on canvas or something. For me, that defeated the whole point. Graffiti is a special and unique thing, but it’s only strong when it’s illegal and in the context of being a criminal act. Painting a thing somewhere it doesn’t belong—that’s where the potency exists. Once you take it out of that context, it’s just kind of ridiculous.

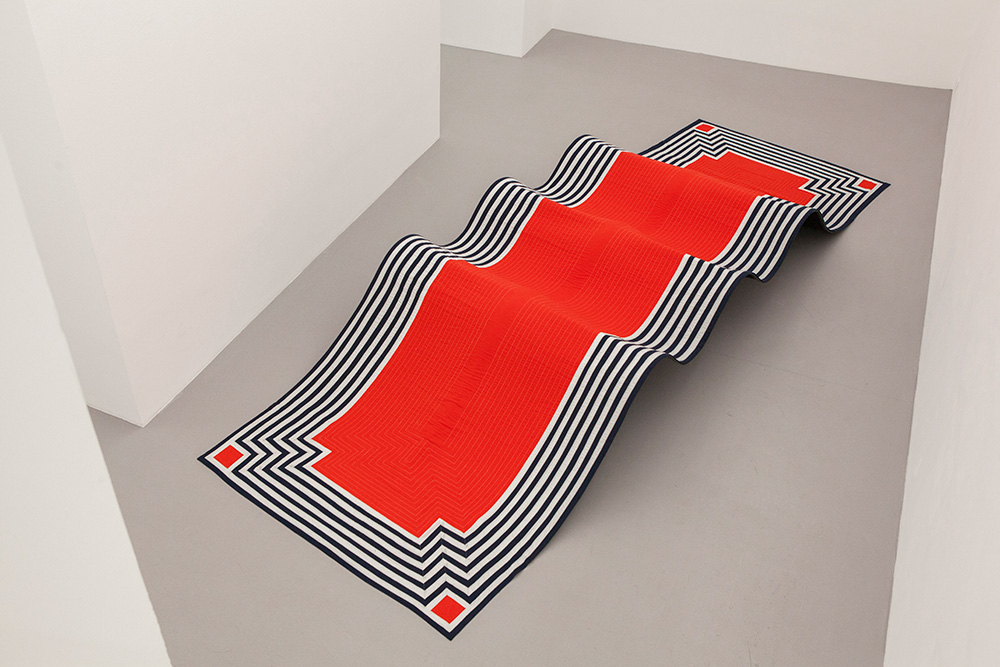

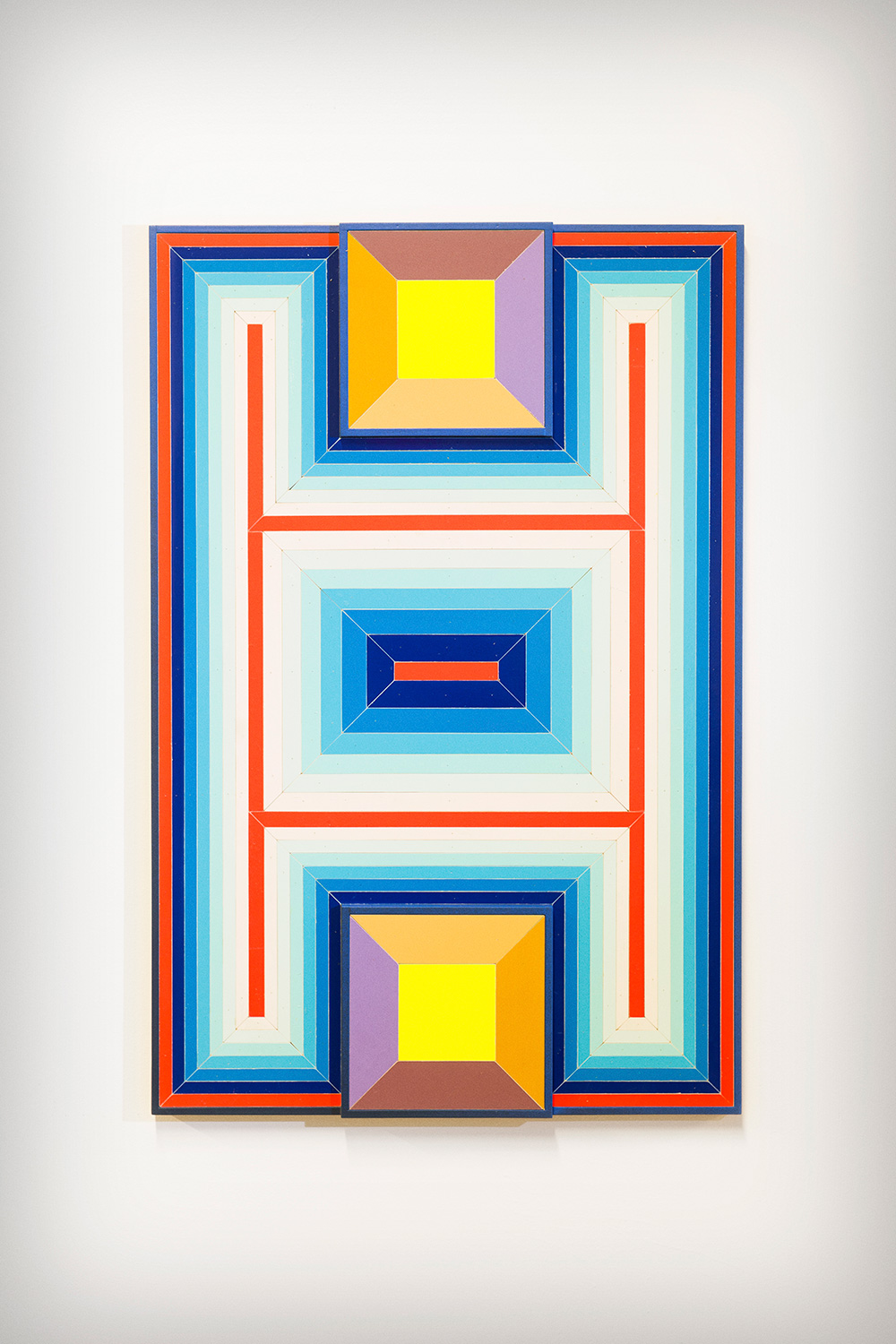

In Detroit, I started going out and “sampling” debris from all over the city to cut up and make assemblage works out of. Instead of creating through drawing or painting, I forced myself to rely on this material and its history. With the help of NEKST, who was living nearby in Chicago building furniture, and knew much more than I did about woodworking, I got started on the basics of using a table saw, a process that limited me to only cutting straight lines.

My scavenged materials were from homes, businesses, churches and schools that had been abandoned. The exteriors of these buildings revealed stories of what was and still is happening there, like the skin of the body of Detroit. It was tragic, but out of that trauma, a new hope was emerging. Detroit, in many ways, built America; now, a new kind of opportunity was presenting itself there. A small group of people were realizing that the traditional power structures had crumbled and they could reinvent the city and make it into something totally new, and at least, idealistically, more democratic. It’s debatable if that is how it has played out, but it is undeniable that the current conversation around Detroit is different from what it was in 2011, and much more positive than it has been in a very long time.

I am grateful to have participated in a small part of that. I sampled little bits and pieces of the city in my work and assembled it in an entirely new way that was bright, colorful and almost psychedelic—a kaleidoscopic vision of a new, hopeful future. Something hopeful and positive was being born out of the decay and rubble that still lives on today. Everything I did in Detroit was as much about the city as it was a personal experience.

When I came back to Los Angeles in 2014, I had to rethink what I was going to do. I couldn’t ethically continue to make the Detroit-based assemblage work anymore. I wasn’t living there, so I forfeited the right to continue to have that conversation. But I had accumulated all these tools for my newfound art process during that time. I knew I was going to continue to use them, but that the work itself and the materials were going to change.

The first couple years back in LA, I continued to work primarily with wood and relied on the same process, but instead started creating all the materials myself in the studio, and stripped down the language gradually over time. What I ended up with was a really polished and kind of futuristic version of what I had been doing in Detroit, but without the ghosts of past generations embedded in the material.

After a couple years of creating that work, I finally felt the need to return to painting. I wanted to use lighter materials, like canvas—anything that was lighter and bigger and not as cumbersome as the heavy and bulky wooden assemblage pieces.

It took well over a year of experimenting to finally figure out what exactly “painting” was going be. I much prefer to use industrial items from hardware stores. I always thought that was something cool about graffiti—before the designer spray paint from the European companies—that we were making works of art with these everyday, practical industrial tools that weren’t ever intended to be used for art. That and the hacker mentality shared by many graffiti writers, who create and improvise ways of making DIY tools, fed into this idea of creating new tools for new methods that didn’t previously exist.

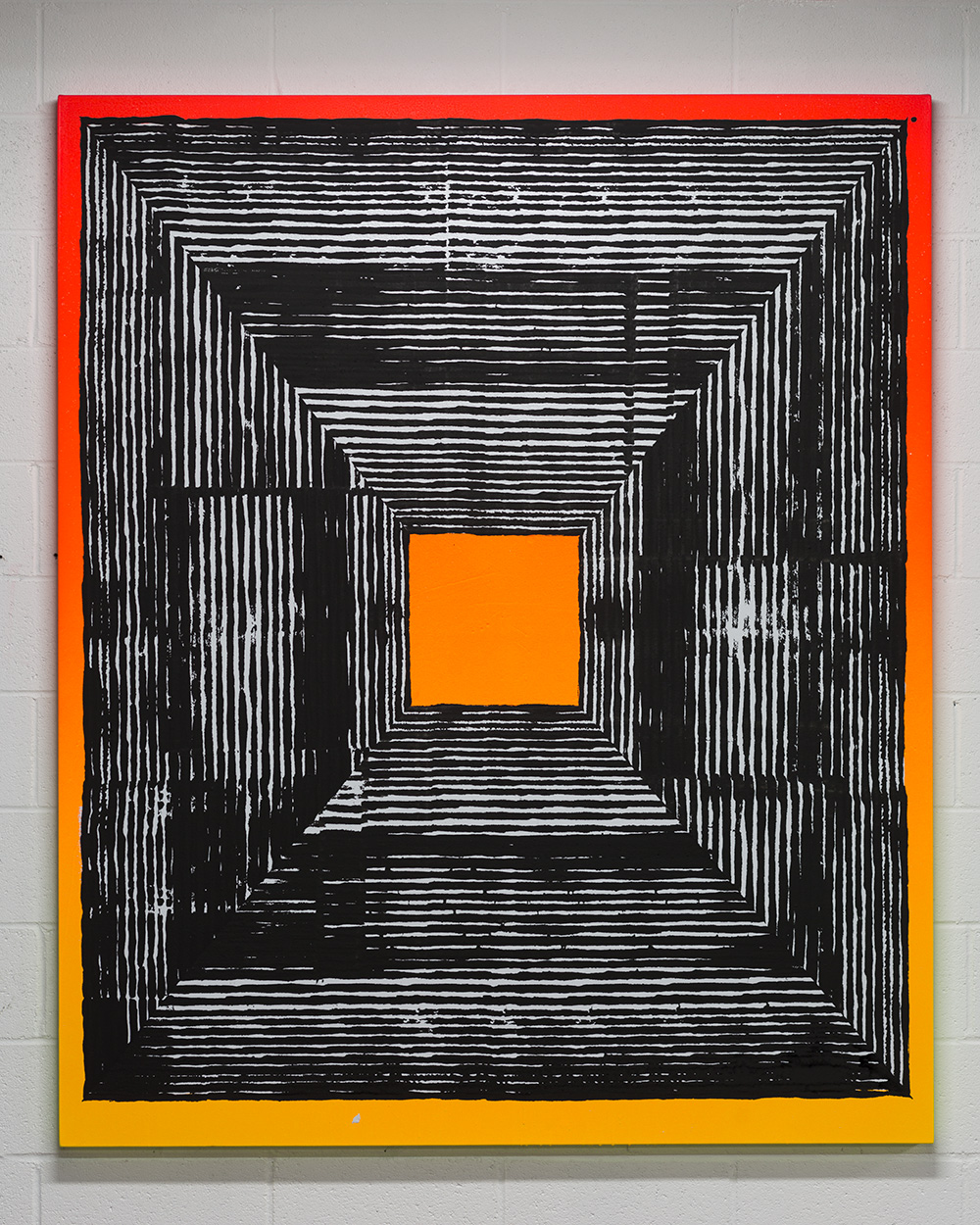

The philosophy behind the work I have been making the last few years is that the authorship is just as much in the tools that create the work as in the work itself. For example, through a Radiolab podcast, I got turned on to this sound composer, William Basinski. He would make these sound pieces where he would record a piece of classical music, maybe 10 seconds of it. Then he would physically cut the analog tape and tape it back together and create a loop to play on a reel-to-reel. Because of the nature of the material, as the piece would play over and over in this ongoing loop, the magnetic dust that adheres to the physical tape where the sound exists would deteriorate and fall away. You literally listen to the life and death of this small piece of music over the course of 20 minutes.

I thought there was something profound and applicable to everyday life about that—this constant cycle of creation and inevitable loss, and how everything’s part of this larger ongoing system of life and death, infinitely repeating over and over in a perpetual loop. I wanted to figure out a way to make my version of Basinski’s sound pieces in a physical, visual way, with painting.

Around this same time, I was really getting into the work of Frank Stella. I first encountered his work at the DIA in Detroit, so these new loop paintings were both a reference to Stella and William Basinski. For each painting, I would create a single unique tool containing a “phrase” by hand. The process of each painting is simply pushing the tool across the surface, mirroring the shape of the body. As I push the tool along its path, the tool starts to unravel and deteriorate and devolves into something totally different as it continues in an ongoing loop. I never reuse the tool containing its “phrase” on another piece; when the painting is done, the corresponding tool gets tossed.

After years spent in the studio in a self-imposed, restricted way of making, finally painting on canvas was a great feeling, and that eventually led me back to spray paint. I wanted to make paintings that captured the excitement and ecstasy of using spray paint for the first time—before it became corrupted, in a way, by a name and style, and all of the oppressive rules surrounding graffiti.

I developed another tool I refer to as an “instrument” that holds 8 or 12 cans of spray paint that all work in unison. It was a way of recapturing that raw energy and youthful aggressive energy of making a mark with spray paint—the way it just kind of splats and oversprays and drips—then amplifying and exaggerating it, and making it one big, massive action of multiple lines.

I’m really interested in engaging a mechanical process where there’s not a lot of room to do anything too overly gestural. I like a practice of mark-making that is almost incidental and restricted, but within this predetermined path, there’s still all of this room for spontaneous or unpredictable chaos to happen.

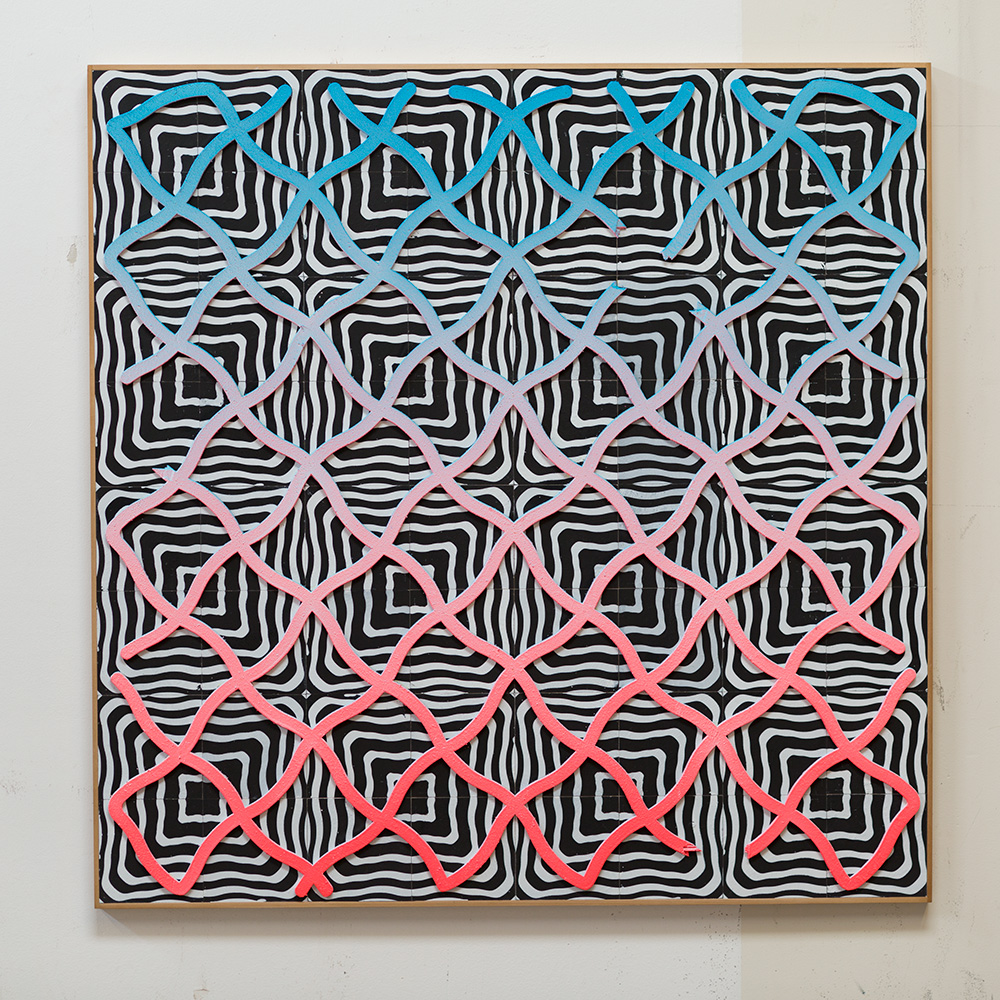

The Spirograph paintings are another attempt to harness imperfections and chaos within a predetermined framework. I remember having a Spirograph when I was a kid and how exciting it was. I got my daughter a Spirograph and was really stoked by her reaction. I saw an opportunity to make something that had never been done before. I wanted to create these rhythmic, symmetrical, almost euphoric patterns that are associated with beauty, serenity and tranquility. Almost like this meditative, hallucinogenic, peaceful design, but composed as this really raw, aggressive, chaotic stroke that is spray paint. It’s a contradiction—something that’s associated with vandalism and chaos. It’s also a way of revisiting my past in an entirely different way.

These instruments brought graffiti back to my work, but I was still able to detach and remove my previous language from it. I really enjoy the idea of a limited mechanical process. I like early technology, like the printing press, for example. It’s a machine process, but there’s still a lot of human hand present within it, and, as a result, imperfections and flaws happen. With all my work, that’s the theme that’s playing out—I try to create a struggle of opposing forces and the unintended harmony that ultimately results. Proper tools will amplify or improve human work, but there is still a little bit of room for flexibility, unpredictability and chaos to happen within this predetermined structure and system. I think that all my different bodies of work play with that idea in one way or another.

Graffiti has enabled me to extend my childhood and remain engaged in the freedom of youth, and when it ran its course and became something different, making art has created a new space and new opportunity to be young... basically naive and hungry.

I am a toy again. Everything is possible, and really, at the core of this whole practice, that’s what I’m enjoying now more than anything

@_revok_