Sarah Slappey

The Well of Fucked-Upness

Interview by Sasha Bogojev // Portrait by Lori Cannava

The plethora of prescriptions society places on personal appearance has been imprinted for so long, that its inherent wrongness, or fucked-upness is taken for granted. Women and increasingly, men, spend countless hours aiming to achieve and maintain dictated beauty standards, resulting in stunted emotional growth, low self-esteem and even unhealthy physical conditions. Dressing young girls in glittery Disney dresses, pots of dainty diminutive makeup and practicing disdain for body hair with depilatory processes causes undue pressure, pain and anxiety. Sarah Slappey’s paintings speak to this unhealthy preening phenomenon.

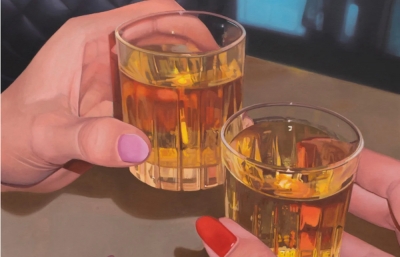

Conflictingly appealing—inviting, smooth and sultry, portraying the media’s ideal, from lips to limbs, her exposed subjects reveal the painful sacrifices imposed by society. By constructing an enticing tension between diverse, but familiar elements and contrasting painterly styles, Slappey teases and inveigles, then confronts the viewer with pulsations of warm, thick blood palpating underneath the velvety surfaces of otherworldly skins. Evoking compassion and demanding understanding, the South Carolina-born and Brooklyn-based artist quite literally offers a hand, but firmly and unapologetically, takes a stance and puts her foot down.

Sasha Bogojev: Tell me a little bit about your new show, which opened recently. How is it different from the last?

Sarah Slappey: In terms of the actual imagery of the body, I narrowed it down a good bit to just limbs—except in two paintings. One is very small, and there's also work on paper. Because it felt as though the amount of messages that I was getting from men about how erotic my work was really upset me… And I just realized, “Oh, I can't paint boobs and butts forever because I can't handle this.” These are parts of my body…

Yeah, and their moms’ bodies also...

That's exactly it. Yes. That's where it came from—the ideas of motherhood and me trying to connect with that. I just couldn't get there. So, I wanted to focus on just limbs for a moment because I think that opened up the identity to be a little bit wider. I think they're female limbs, but it's not so gender-focused, and I think, because of that, our conversation about bodies and what bodies feel like can become a little more open.

I didn't notice the pivot, I guess, because I’ve always connected to your work through hands and objects.

I have thought the same thing. I know that I can't control other people's read of my work. I would be chasing that forever. But it made me think that, as an artist who makes representational images, my work is sort of like a stew, where I'm always adding in ingredients to make the final product. So I thought, “Okay, maybe I have too many carrots in this stew. I need to add in some new ingredients or stir in other ingredients so that my stew becomes this thing that I really intend it to be, and not a carrot soup.”

I love that metaphor! But was it easy to give up a portion of the ingredients because of, basically, how others feel about it?!

I've had some people push back on me and say, “You should be making whatever you want, who cares how your work is read.” But, I do care because I have something I want to say, and I have something I want to say about my body, and if my message isn't coming across the way I want, then, I'll push it. I'll push forward so that it does.

So, when you said that this body of work is supposed to portray a wider picture, does that also include male bodies?

I don't know what it feels like to be in a male body, so I don't think so. For instance, I had someone ask about how they appear as pink, white fleshy tones. I spent a lot of time thinking about that too because I think that representing bodies of color is so important, but it's also not my place to speak about that. Because I don't know what it feels like to be in a body of color. There are a lot of people who are making figurative work about black and brown bodies, and I don't want to take anything away from what they’re doing. My job is to listen, but not to make any kind of representation that would come across as if I know what that feels like because I don't. That's my place.

How would you summarize your work?

I think like the alienness of being in a body. What stood out for me in this body of work, is it felt way more elaborate and more refined. I thought that widening the conversation could be a good thing, but simultaneously, I wanted to dial in the detail and the conversation around the other elements and turn that volume up. I really didn't know what those details would be until I started working. And it all ended up being far more autobiographical than I intended, which is always a surprise. You turn on the faucet and just see what happens. I'm actually just now sort of going back and reading the paintings for myself, and seeing some of the decisions I made and thinking, "Oh, I think I understand that now.”

What are some of the things that you now see that maybe you weren't aware of?

There are two things. One, after my last show in Zurich, I spent a month in Europe and I traveled around and spent a lot of time in Italy. Being there and being in the art world of Europe is a totally different experience. It has these roots that connect down to really, really deep history and into religion, and the body specifically, that I don't get to experience in New York. I felt like this glut of imagery about pain and the body was all around me. And I don't think I realized how much it seeped into my practice and my mental imagery bank until I came back.

What particular elements show this influence?

Like the bows pinned into the hands, that was intentional as a sacrificial moment. Then in the big painting with the blue and white gingham background, there's a braid that kind of goes over the top with hairpins that stick out. As I was making it, I thought, “Oh, like a crown of thorns.” I can't stop thinking about that now. It was a small realization at the time and now I just keep thinking, "Oh, I did that without recognizing it." And that's really something.

Some would probably argue that Jesus spoke through you, but I wouldn't be one of them…

Right. Maybe the gross violence of religion and humanity spoke to me. But yes, you're exactly right—some would argue that I had a religious epiphany.

Are they then also a commentary on the religion itself?

No. I have strong thoughts about Christianity, because of the area that I was raised in, where there are a lot of extremes in terms of religion. But I don't have interesting thoughts about what that is, I just really hate it. Maybe I'll explore that one day. I think these images more so come from the fact that when I was in Europe, there was just blood and guts everywhere in all of these images. And I loved it! It was so hyper-violent. When it comes to violence, the U.S. operates on two extremes. One is in all of our media to the nth degree, but at the same time, we don't have a relationship with blood in the body. I guess the comfort with it that Europeans have in their daily lives, with these images of, say, an eviscerated Christ, did not seem so internalized as religion here, and I love that.

So how does that affect your work, which often revolves around your love-hate relationship with femininity?

There's also something about being a woman. I think everybody remembers when you first start getting your period and blood is everywhere. No one really talks about it, and it's supposed to be not that big of a deal that suddenly your body is bleeding out huge clumps of blood. It's like, “No, no, no, just contain it.” God forbid it shows on your pants in middle school! What a deep humiliation.

So every woman knows that feeling of standing in the shower and looking down, and there is a river of blood underneath you. I think I had those feelings in Europe, “Oh, okay, so now we are all comfortable with blood.” I think, as a woman, you have a very different experience with all that.

I think that's a really impactful aspect of your work, and this newer work is so polished and alluring that you want to look at it and appreciate its beautiful, elegant, silky smooth appeal. Then, in between, there's shaving cream, scars, and trickling blood.

I actually love what you just said. That's the whole point of it. When I was 20, I think I had a professor in school tell me that the work is sort of like this really beautiful spider web that draws you in, and then a tarantula comes in and eats your face. I don't know why, but experiences in my life made me feel so connected to that feeling.

What are some of the aspects of the work that you’ve focused on recently?

I've really enjoyed painting the feet. I feel like I could paint a hand with my eyes closed almost, but I don't know, I don't have enough mental training with feet yet. So every time I do them, it's a challenge—but exciting. Also, the range of objects I include in paintings has grown a lot, and I think that'll keep growing. Going back to the stew, the stew is just getting more ingredients, or I'm putting more words in my dictionary all the time.

So, you seem to be playing around, exploring, between an anatomical and manipulated effect.

I think it's because the legs and feet are new to me. One of the things that I love so much about feet is their puffy veins and the fact that blood pools in certain ways, like around your toe knuckle to the bottom of your feet, and the veins sort of curl around in your instep. I worked on painting them in sort of that smooth, puppet-y style at first, and it just felt like I was missing that grossness of feet. Hands aren't so gross, but feet are gross in the way that I love. So I tried a few things out, but that's where I landed because that’s the way feet feel to me.

That actually explains what I see in the images, hands looking so smooth and inviting, while the legs and feet are so rough...

Well, the hands caress and feet stomp. I wanted to feel the blood pulsing in them. Maybe over time, they'll go a little more gentle, like the hands, I don't know. I'm sort of feeling it out as I go along because they are a new object for me also.

Can you explain your approach to the background and foreground?

The background in all of the large paintings in this show is a type of grid, which are everywhere, though we have this ability to ignore them. Their structure is also a very powerful force to push against. Like fucking up something that is so perfect kind of highlights both the perfection and the chaos, at the same time.

So, in the shower scene painting, it's bathroom tiles, while the other ones have more of a reference to the American south. There's one where the grids are sort of woven together, and that's based on Wicker furniture that we see a lot in Southern home decorating, along with gingham plaid fabrics. We grew up wearing gingham, so that pattern appears in the big hair bows and such.

I heard your reference to the South coming through in your work in the Sound and Vision podcast, though it was something you weren’t really conscious of. Can you maybe talk a bit more about that?

Every year, I just keep talking more and more about the South, and that surprises me. This work is much more biographical than I expected, planned, or anticipated. I think when you become an adult, you start reckoning with things that you thought were true or things that you knew to be true when you were growing up, and how this impacts or has been formed by your family and your surroundings. It takes stepping out of that and gathering enough adulthood experience to look back and think, “All of this is sort of made up, and none of it's real, and a lot of it's really fucked up”.

The South has extremely stringent gender roles, and one of the great things about being in New York is that people are allowed to create their own identities more than any other place I've been in the US. So having that dichotomy between being an adult here, and I've lived in New York for 15 years now, it's long enough that I have a “before and after” in my life.

When I'm looking back now, I feel that there is a river of identity that divides what I used to know to be true and what I know now. And yeah, I think mentally spending time in that place, picking it apart and identifying it, and then hating it and loving it is okay. It's what all these works are about and, yeah, that does surprise me.

I think you found your well of inspiration and motivation, and now you keep digging deeper and finding more.

The last body of work that I showed with Sergeant's Daughters was also about gender and the body and my love-hate relationship with femininity, and this body of work is the exact same. There’s a big tangle within me. Maybe I'll keep exploring that, but I want things in the studio to change all the time. I think you're always sort of dialing down, but once you get to a place where you feel like you've hit something, then you have to go back up to the surface and pick another spot to dig. As you said, there's a well of fucked-upness.

Tell us more about some of the elements that you have in your work, like those ribbons and safety pins?

Well, that's a biographical thing. My mom is an expert sewer and embroiderer. Growing up, we were constantly dressed up in these beautiful dresses she would make. She had all of these spools of ribbon around that we could choose from, and we wore big giant hair bows that were, like, the size of our faces. I still love a beautiful bow. I love satin and silk. But at the same time, it's like dressing little girls up as wrapped presents. It’s creepy, and it's odd and grotesque, not that my mom or anyone in my family did it with malintent. But, looking from a distance, you realize there is something very seriously wrong here.

And what about the pins?

As she was fitting us for these dresses, they were all held together and fitted with straight and safety pins. So, there was always a risk of being stuck with one! It's these moments of microaggressions for a little girl's life, tiny violence that again, you step back and look at from a distance. I think the little boys were playing with GI Joes, and we were being constrained and made sure that nothing was out of place.

And when you speak in this way about it, do you get any feedback from your family, from your friends there? What’s their reaction?

I actually haven't talked to anyone from the South, including my family, about my relationship with the South. With that being said, I don't think that it would be surprising to them at all. I don't know, maybe I make this work because I can't talk to them about it. But it's like a thorn in your shoe that you have to explore and figure out because otherwise it can't be resolved. It's also one of these things that are bigger than you, bigger than life, and much bigger than I have the words for at the moment. I think even the way I'm talking about it right now is too simplistic. Because it's not just the South, I think it's so much bigger.

What do you imagine that people experience when they see your work?

I think about that a lot. I want people to feel a sense of joy, pain and shame. I want women to feel understood by men, I think, in a way where they can stand in front of one of these paintings and think, “Yes, I know this feeling and I haven't put it into words; but I want other people, I want men to see this, to understand something”. Even though I don't even know what the something is.

You must have something intentional in mind about the male reaction, something you’re trying to convey.

I think empathy. It's not like I just make paintings for women. I want men to feel the humanness of being in a body and the constraints of being in a body. Also the body and culture and pinching and pulling and piercing because that's all universal. We all have skin, muscle, and tissue, and fat.

How often did you come across someone offering feedback that they had such an experience?

I don't know. As much as I think about my audience and how I’d like them to feel after the work is done, I don't know how important it is anymore. It's just kind of sealed up. And maybe if I'm being honest with myself, maybe as I'm thinking about the viewer, I'm just really talking about myself. I'm in here all day, every day. So if I made work for other people and truly made work for other people, I think that would be a really awful way to spend my time.

Sarah Slappey’s Self-Care was on view at Sargent’s Daughter in NYC this past fall.