But do you ever make work that's directly referencing a person?

Yes, and it's usually a process that includes me inviting them into the studio and taking photos. I start with a sketch to kind of direct them and guide them through. It's usually when I'm looking for very particular lighting on a face or speaking about someone, because sometimes I don't want to just depict someone's beauty. I mean, that's boring. You can see how beautiful they are on their Instagram profile, but there has to be something else. I usually work with people that have a history in performance, so I'd ask them to just play a role and record it, and there's a frame that will be suitable to blow up into a work of art.

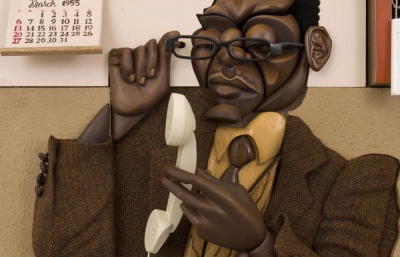

I feel like your work is celebratory and joyful in nature. The characters feel so alive. Then, actually, when you sit and look at the characters in particular, none of them are smiling. Most of them barely even have their eyes open or are looking up. No one's looking directly at you. There's almost a certain sense of melancholy. To what extent do you agree with this observation? Is that sense of moodiness deliberately present, and if so, what role does that play for you?

So yes, it is true. There is a joyful element, and I think it goes back to the thing I said about happy hour culture. I guess the assumption is that when it's colorful and there are drinks on the table, we're all good. But then there's almost like a personality or a role that people tap into in those spaces. Cool people don't smile. There's an attitude about it, and that's why I've always tried to include someone with a cigarette. Or they’re almost so preoccupied with themselves that they don't entertain whoever's looking. It feels like a moment that's kind of like a stolen image. You could be somewhere, and you're like, “Those people look so cool,” and you secretly take a photo. I'm a voyeur. There’s a feeling that I'm looking from the outside-in, because my personality doesn't correlate with the cool crowd that much. I don't have that pompous-wearing-shades-indoors kind of attitude. I feel like I'm more open, and I'm likely to smile more in my work than the people who are my subjects.

I always try to figure out to what extent the artist is present in the work. Are these self-portraits masked in some way?

I feel like I play the role of a documentarian. I'm just like, “Hey guys, look at these people. I saw these people earlier. I just enjoyed their aura!” I think maybe it's what I referred to as the audacity of the youth, because I feel like I've lost it.

Since it's come back up, can you talk a little bit about what you mean by that?

I feel like the youth are quite audacious. A lot of people almost lose themselves when they are young and in pursuit of a particular lifestyle, and when it actually works, it's actually delightful to witness. I feel like there's a lot of that in Cape Town. It's a weird city because a lot of people are models. It was something that was very appealing to me when I moved here. I was like, Everyone is beautiful and youthful. There's a lot to write home about. A lot of people are good looking here. It's been my point of reference, and I'm almost trying to tell the world about it.

But then it's not an energy that only exists here. It's like anywhere you go, the youth are running shit. They're dictating how things are supposed to go. They're looking good in thrifted outfits, and so it's like they are so audacious and future focused, very forward and ahead.