Zoé Blue M.

Finding the Sound of Emptiness

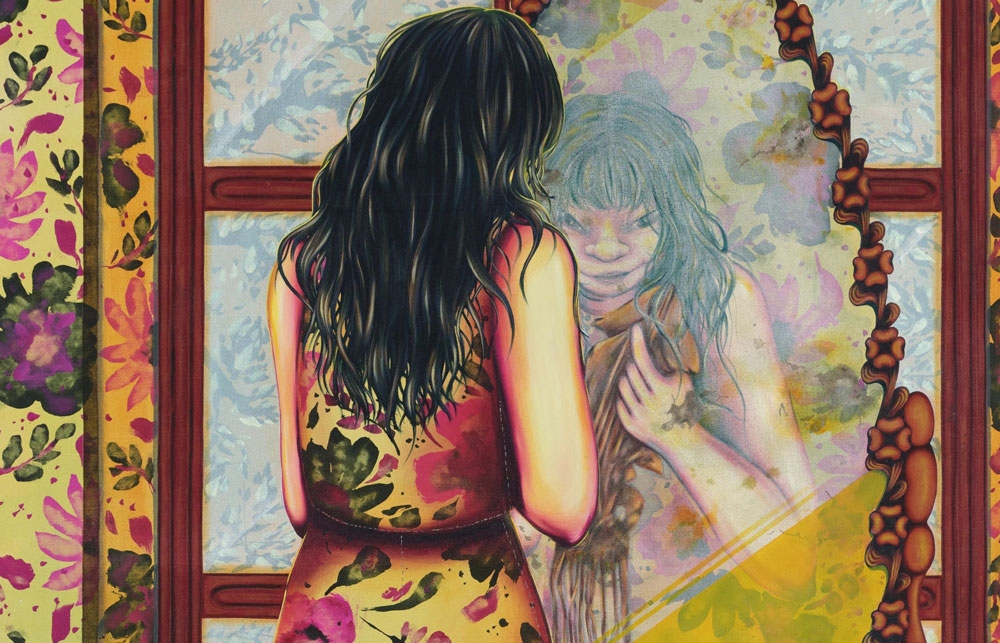

Interview by Holodec // Portrait by the artist

Prior to her graduation from the esteemed MFA Painting and Drawing program at UCLA early in 2023, Zoé Blue M. had a resume that would be the envy of even the most jaded mid-career artists. Exhibitions with Jeffrey Deitch, Page NYC, PM/AM, and Anat Ebgi, along with being the 2023 recipient of the MFA Fellowship in painting and sculpture from the Dedalus Foundation, created quite a significant buzz in the contemporary art scene.

Now the Toulon, France-born, Japanese-American, Los Angeles-raised artist, is summoning references from personal memory, folklore, philosophy, and pop culture as she creates large-scale paintings that represent a new view on a multicultural identity. Her energetic paintings are often at the precipice of action with wide-eyed figures wafting in and out of their surroundings. With a recent MFA show behind her, I sat down with my friend to discuss topics relating to identity, audience, and inspiration.

Holodec: What got you into drawing figures first and foremost versus, let’s say, landscapes?

Zoé Blue M.: Or literally anything else.

Right? You know, I see clear influences from manga.

Yeah, there is, totally. There’s something about it that, for me, was so accessible while growing up. I also mostly paint figures to life-size. So there’s this one-to-one relationship between a figure in a painting and the figure that is you.

You, the audience, get to see yourself, right? And many of the figures are people in your life, too.

They can be. The figuration now comes from an amalgamation of all the women in my life or myself, which originates from wanting to make paintings about my family. I specifically wanted to make paintings about my grandparents or Japanese family but I found it disrespectful to use their faces. It felt like putting words in their mouths.

So, I found a solution where I was doing these figures that were the embodiment of many women, almost creating an icon. The figure can represent many women, she can be placed within a scene. And the surroundings become the force in creating an identity for that figure. It was just a way, literally, not to be disrespectful to my grandmother or something like that. I didn’t want her to be upset. You know, she would say, “Don’t show my face.”

But I mean, it was finding a new way of approaching portraiture without using a figure that was a specific person. How do I do it through a scene? In tone? Through objects? Metaphor? When I first started figurative work, that was my approach.

What triggered the shift from figures?

I guess I just got more interested in the tone, spectatorship/viewership, and less so in the individual person. My last body of work was about voyeurism in all the different senses.

Oh, I was going to suggest that because a lot of these feel voyeuristic.

Yeah, thinking about how to look. A big idea I wondered about was how to make a painting, and I don’t even know if I succeeded, but in my brain, it’s working, where someone is watching and potentially the figure in the painting is complicit or unaware of being ogled. How do you make someone appear as if they don’t know they’re being watched? All those paintings were iterations of different types of looking and being perceived.

Why is that a theme you’re interested in?

Going back to reading Love Hina and my childhood reading manga. I was thinking about a young East Asian girl’s relationship with sex, and how they’re being stereotypically fetishized in so many different ways. Yet, they might be going through life and also thinking about it as their kink. I was curious about the embodiment of that. I was remembering the feeling of consuming all that eroticism, rejecting it as bad, and yet knowingly trying to embody it. That was the general idea. Reclaiming something, right? Reclaiming the stereotype. When you think about anime and sex, you’re going to think: panty shot. A lot of it is a bathhouse scene, an upskirt shot. Being submissive, being cute. These are pretty problematic ways to think about a woman’s sexuality, but at the same time, there is something really hot about it. I had all those thoughts about sex, and how it has moved through pop culture or art history.

As Asian Americans, we hate that stereotype.

Yeah, but at the same time, I love an upskirt shot.

I would say we hate that it’s a stereotype, but when you go to Asia, that sort of thing is actually everywhere. It’s not even a stereotype because they really are into upskirts and panty shots.

They’re doing it, right?!

Yeah, they’re the ones making the movies, the pornos, the comics that show these kinks.

And that was big for me.

And that was big for me.

So it’s almost unfair to say, “Oh, they are stereotyping us.” Because we can be the ones doing it, creating the examples.

It was this thing, this sort of duality of the problem that I had in my own brain where I couldn’t stop thinking that it’s this horrible thing that victimized me growing up, and at the same time, it’s also something I’m culturally subscribing to, you know what I mean?

We’ve always been the subject of voyeurism as minorities, right? The gaze is always upon us, the other. And we hate—or are anxious about—what they might think.

We know we’re sometimes complicit. So, it’s an Asian thing and also a hugely Asian American thing. Some of us are against that rhetoric and others are completely aware that we are a part of it.

My friend Kelman Duran, who’s an artist too, talked about nostalgia as “we’re all attached to nostalgia because that’s what actually gives us hope for the future.” Because nostalgia isn’t so much the details or even the objective reality of our past, but just the feeling. And the feelings—which you cover here (in your writing) about reverie and all that, it’s more about the feeling of the memory and the thought, those feelings I think, that are the purity giving us hope for the future.

I think the way that I started looking at my paintings is not looking at time in a linear way. Everything is connected, I’m picturing time folding in on itself constantly. Also, if you have a relationship spiritually to your ancestors, always finding their presence around. Thinking about time moving in that way. So much nostalgia is paying homage.

Actually, there’s a part in your writing where Nishida talks about how time is both one and many, changing and unchanging, past and future in the present. That reminds me of the Diamond Sutra, a Buddhist text where in essence... it is not going to do it justice to try and summarize it…

It’s so hard for us to put into words.

But in essence, it’s saying that the past cannot be retained, the present cannot be maintained, and the future cannot be attained. So it’s like what you were talking about, that everything is kind of one and the same, it’s in flow.

It’s in constant flow.

Were your grandparents into art?

My memory of my grandparents who live in France, and the way they thought about art, has always been informative for me since they were super into Asian culture. And I say Asian culture specifically because they had no real understanding of the divisions between different cultures. I would be finding a katana and a Chinese dragon.

The French have a word for that. Chinoiserie. Chinese-y, but really meaning Asian-y.

Yeah, and the Orientalism movement. But the way that I look at my relationship with my Japanese side is in a beautiful, more spiritually guided way. My grandmother’s relationship to being Japanese American is immigrating here and marrying someone who came out of the war, came out of internment. Culturally for them there was a lot of rejection.

Yeah, I have certain relatives who were very intent on assimilating. They were like, “No, we speak good English.”

“We’re American.” Which is true, they are, you know. Then there’s my grandmother on the immigrant side who doesn’t really identify with the Japanese-American community because she’s Japanese. There’s this mix between the two ways. As we got older, what I found interesting was the duality of rejection. But the constant underlying spiritualism is everywhere. She would have this attitude of, “No, not subscribing to that.” But at the same time, she would say, “This is a good omen here, a bad one here.” Doing things without saying them and growing up with an underlying spiritual and cultural current.

I had similar instances with my mom where she’d be like, “Oh, we don’t do that in our culture, in our family.” But then on the flip side, she’d also be like, “No, we don’t do that. We’re not like those Asians. We’re American.” As a kid, I was thinking, “So, which is it, Mom?” She’d cherry-pick when to leverage the Asian culture and when to leverage American culture.

Right. Then you grow up and go to school and they’re saying, “You’re Asian.” You’re there thinking, “Okay, but I don’t feel Asian in the way that you’re sort of saying that to me.” When I started making work, I found it really difficult to put my finger on anything. And as I continued I realized that putting your finger on it was an agenda that was forced onto me.

For example, how do I make it easier for you to understand all the different things about my background? What does that mean, why do I look like this, do that, eat this? The more I read various identity philosophies I realized being able to dilute things in that way wasn’t something I wanted. It simplifies it in a way that isn’t necessary. The truth is that it’s complicated, but that doesn’t have to mean difficult. I want my work to operate in that way. It isn’t trying to figure everything out or be easy to understand, but still be generous. Simplifying it for anyone... to me, it’s not something I’m interested in.

Your work is so extremely detailed. What’s interesting to me as a musician, from a fan’s standpoint, is they’ll be like, “I’d love to hear a Holodec take on this genre.” So I can even see myself thinking, “I wonder what a Zoé approach would be for something like x?” Because one of the big themes in Asian painting was the concept of wu, which is emptiness. Negative space. Where they only draw a bit of foreground and a bit of the background and the majority is negative. Yet we see everything. I was just thinking, “I wonder what Zoé’s take on that would be.”

And then there’s also mu, which I think Miyazaki explained as the sound between claps [claps].

I think in Japanese it’s mu, in Korean too, and in Mandarin it’s wu, but it’s all the same character 無.

The emptiness. It’s actually one of the main forces of the next body of work that I’ve been thinking about. We’re on the same page. It’s the in-between. I’m thinking about paintings that have no figuration existing as the sound of that emptiness.

Your work really resonates in the digital realm partly, I think, because it is so colorful.

There are some really amazing painters that don’t read well digitally but are phenomenal, I mean really phenomenal in person.

Is that a conscious decision of yours?

Not a conscious decision in terms of my choosing to do it as a move. But probably a conscious decision in the sense that my inspiration is a lot of digital imagery. It’s a huge part of my brain.

Manga and anime… so much is digital.

Evangelion is half-painted if not all. So many are these beautiful paintings, like Miyazaki, all hand done. But they were made to exist digitally. It just so happens that’s my reference point. I’m looking at a lot of images and replicating them. It ends up looking good when it turns back into the digital realm. That’s just something I have to live with.

Do you have an interest in ever doing digital painting?

Oh, not at all. There’s something intoxicating about pulling it off by hand, it drives me crazy.

Well, that’s a good segue to medium and tools. Part of your inspiration is the medium itself.

I paint with all acrylics, which can be hard. Dries fast. I think I got into acrylic painting because I like that it was sort of plastic, but now I love how much I can use water. Half the paintings are made on the floor because... gravity. They’re mostly washes. It has a nice relationship to textiles since the paint really sets into the canvas itself. It’s an exciting process for me. I love looking at animation and trying to craft it in a painterly way. Making something feel indexical but based on cartooning language.

That reminds me, Issey Miyake said what he loved about fashion is that you have to work with the textile. You have to learn it. Each type of textile has different properties, different rules, and the artist has to conform to the limitations of what the property brings you. So for him, so much of his inspiration was medium, right? It’s very obvious, from the pleats to your bag.

Oh, yeah. My bag. Bao Bao bag. He says those things about form, it’s very Japanese. There was this very famous movement called Gutai where you think of material as having its own agency. Instead of fighting it, you coexist. Like, how do you make work where you and the material have the same presence? I try to think about that with painting. If you force acrylics to do something it doesn’t want to be, it rejects you. You have to find your balance. Everyone has different ways of making that relationship whether it's air, water, a medium... If you fight, it won’t look good. It’s fun when you find the way, it feels spiritual.

What level of importance do you think we should give to institutional orthodoxy? Because they do define a lot of what’s considered good, right, and what’s not. I hate that. And what I love about the audiences, the real fans, is that while all the critics were initially hating on hip hop, punk, Wong Kar Wai, or Hou Hsiao Hsien films, the people, the audience said, “Nah, there’s something great about it.”

Well, the only way to do well is to stay true to the thing you believe in, isn't it? Because anybody that we look up to has done that. Painting is funny, it has gone through so many movements where it’s apparently dead.

Painting is so institutional. So much of what is considered a good painting is that some prestigious gallery had this exhibition...

That’s a big way. You know, when you’re matriculating and want to be inspired by, for example, Asian artists and you’re trying to research your culture, you do have to go off the Western institutional grid. So, you find artists or makers that have done well elsewhere, but not in terms of the sphere that seems to claim importance over you. Trying to find a balance because you might want to be a part of both worlds. How do you be a part of both? Painting is a lot of regurgitation. Sometimes it can feel hard to be innovative. But then, much of the success of the figurative movement is from working off past figurative works, recontextualizing them. In no way is my work functioning outside of that conversation. I always say that if you know what I’m referencing, you’ll discover I steal every single thing I do.

We all do as artists. I have a question that I like asking our peers. Who did you first copy? Me and a lot of my homies, we all wanted to copy The Neptunes. Just kind of the thing at the time. Or I can say, I try to copy Taiwanese New Wave cinema but in a musical way.

So many of my paintings are copying films, too. There are paintings that I have made that are practically one-to-one. But, it’s the power of your hand translating something where it no longer becomes identifiable. The majority of my paintings are ripped from an Impressionist or post-Impressionist painting that I love.

Compositionally?

Yeah, compositionally or also the entire equation. The same format, I just shifted the style. But in terms of the operation of the painting, it functions in the exact same way. Everything is just ripping this or that. A lot of the time I’ll be watching something, pause it, and that’s the painting right there.

Freeze the frame…

...and make the painting. The power of having a language is that if you freeze the frame and copy it, it won’t be the same thing. There’s an energy to your hand.

All artists copy and if you’re true to yourself, the result will never look like the copy.

I think what’s important is not to do it too blindly. I have a lot of faith in my subconscious, and it isn’t because I let it do whatever it wants, but I let it speak to me and then I research it. I have the inkling to make an image because I’ve seen something, I know it’s for a reason and it’ll come to light. There is always a reason images are so powerful. They hold within them probably all the things I have been thinking about.

Zoebluem.com // This interview was originally published in the Fall 2023 Quarterly