Josh Jefferson grew up in Santa Cruz, California and now lives in Boston with his wife and son. When he put down his saxophone and picked up a paintbrush four years ago, he found his groove swiftly, so it was clear the transition was a matter of fate. His creative endeavors up until that point fueled confident, powerful gestures, and even though he took up painting fairly recently, his development as an artist has been lifelong.

Portrait by Todd Mazer

Some of us are drawn to perceived challenges. If painting effortless, emotive figures seems beyond reach, there might be a curiosity about how something so simple could express so much emotion. It’s all in the gesture, and J.J. has it down. We had a rapid-fire conversation about artist’s artists and the necessity of owning your moves.

Kristin Farr: Give me a laundry list of artists you like.

Josh Jefferson: Ken Price sculptures, Jean Dubuffet, Milton Avery, Misaki Kawai, Edvard Munch, Cecily Brown, outsider art, and my son’s art.

Are there artists you like to look at in depth?

The funny thing is I look at them, but I don’t. It comes to a point where you have to stay in your own head. I’m pretty impressionable, even subconsciously. So I kind of look, but then I don’t. Instagram is like that. There’s a famous Philip Guston quote where he says we’re littered with images in our head. And now we’re super littered, like on steroids, with Instagram. You can see too much. That’s why I don’t follow too many people. In fact, I don’t even follow people I like because I don’t want to see.

I feel guilty unfollowing people.

I was at my opening at Gallery 16 and a guy came up to me and said, “I love your work. You used to follow me.” It was such a post-Internet comment.

Photo by Todd Mazer

Does Instagram help you sort ideas for your own work?

Sometimes. I’m definitely into the numbers, which shows my vanity. It’s weird. Sometimes, as an artist, you’ll have a gut reaction to your own work, and you know what’s good in your own milieu or whatever, but if I don’t get a response on Instagram, I get kind of bummed [laughs]. And then the bar gets set higher. It’s so superficial, in a way. I’ll post something I really like, a collage, and if it doesn’t get a certain amount, I get disappointed. It’s ridiculous. I’ll get 1,000 likes on one thing, and if the next thing doesn't get 1,000, it’s not good. This is how neurotic I am: there are artists I really respect, and if they like it, then I’m OK [laughs]. It’s so silly.

On the flipside, just seeing images, and the intimacy—Cecily Brown is on Instagram and she posted a studio shot that you would never see on her website. I didn’t know she was on Instagram, and I posted another studio shot of her and said I thought it was 2004, and she commented “2002.” There she was! It’s such a new paradigm for artists. We’re such visually hungry people that it’s the perfect way to connect for us. Everyone’s on it. And you have everyone from Gagosian to the corner store gallery, so that’s great.

Are there any artists that you feel you are in conversation with, even if you don’t know them?

Some are alive and some are dead. With Munch, I’m starting to get closer to that wavy dark energy, if you will. I had to get over Misaki Kawai and Tal R. I kinda can’t look at them anymore. I wanted to be like them so bad, I had to stop looking at them. But I do think I have a dialogue with Misaki. Our language is closer. There’s a certain kind of irreverent, goofy, strident aloofness there, and also a dedication to the work.

I should have asked her to interview you. I like to think about simplifying shapes to the point that they’re recognizable but nearly abstract, and you both do that. With just one tiny brushstroke, you are able make a killer side-eye glance.

Awesome, that’s the goal. The simpler, the better. Look at someone like Milton Avery. His paintings will have a chunk of sky and a chunk of land, and it’s so simple. The best stuff is really simple, isn’t it? Even great music. When something is reduced down to the most core, necessary elements, you get something that’s real.

Since you’re colorblind, do your paintings look different to you than other people?

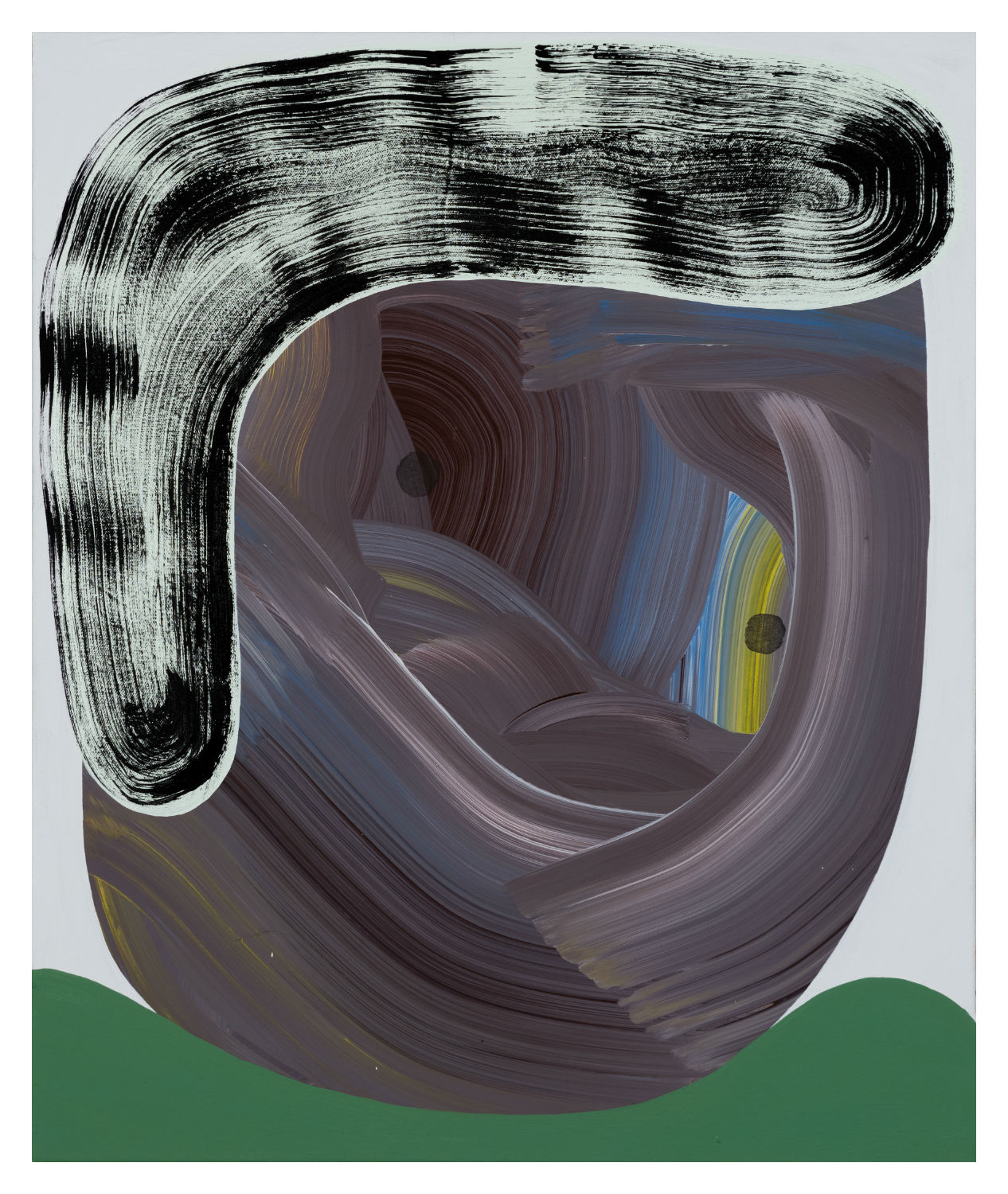

Only with certain colors. In fact, I just did a small self-portrait, and it’s kind of like a creepy Frank Auerbach painting. It’s smeared paint, and I really wanted brown hair, so I mixed what I knew was brown, but it didn’t look brown. So I made a dark green, but was convinced it was brown. Then I showed it to someone who said, “All these greens look great.” And I was like, “This is beautiful brown hair, shut up.” But I realized it’s OK. It’s working for me. I stick to bolder colors so I can see them, but when things get mixed, the weird gradations start looking like mud to me. Greens and browns look similar, and so do blues and purples. Pink and gray look the same to me.

That one kills me. Can you never see pink?

I love pink. I’ll look at a Guston and all of his pinks, and it’s weird, if I look at it quickly, I can see them. Then I look again and it’s back to gray. Or it’s just gray the whole time. In fact, I did a whole series of pink paintings and I showed my wife, and she said, “What’s up with the pink?” And I was like, “This is a subtle gray!”

Photo by Todd Mazer

I read that Ellsworth Kelly only liked colors that were easy to describe and he didn’t like muddier colors. Maybe he was colorblind too.

His colors are so primary, so distinct.

I don’t think my son is colorblind. It’s hereditary but skips a generation. My grandfather was colorblind. I’ve tested my son, and he’s corrected me a couple times, so I know he’s OK. He’s only four.

Was it a memorable moment when you realized you were colorblind?

It was, actually. I was in elementary school, and a teacher gave me a coloring book calendar of ducks, and she asked me to fill in two different colors. I did the opposite of what she asked, and she said, “Oh god, I think you’re colorblind,” and I cried because it sounded awful. My mom had me take a pretty far-out test—it’s obviously very optical. There were grids, and if you could see circles between the grids, it meant you could see colors. It was pretty trippy and looked like contemporary art almost.

Did you ever purposely make a painting that would look different to you than non-colorblind people?

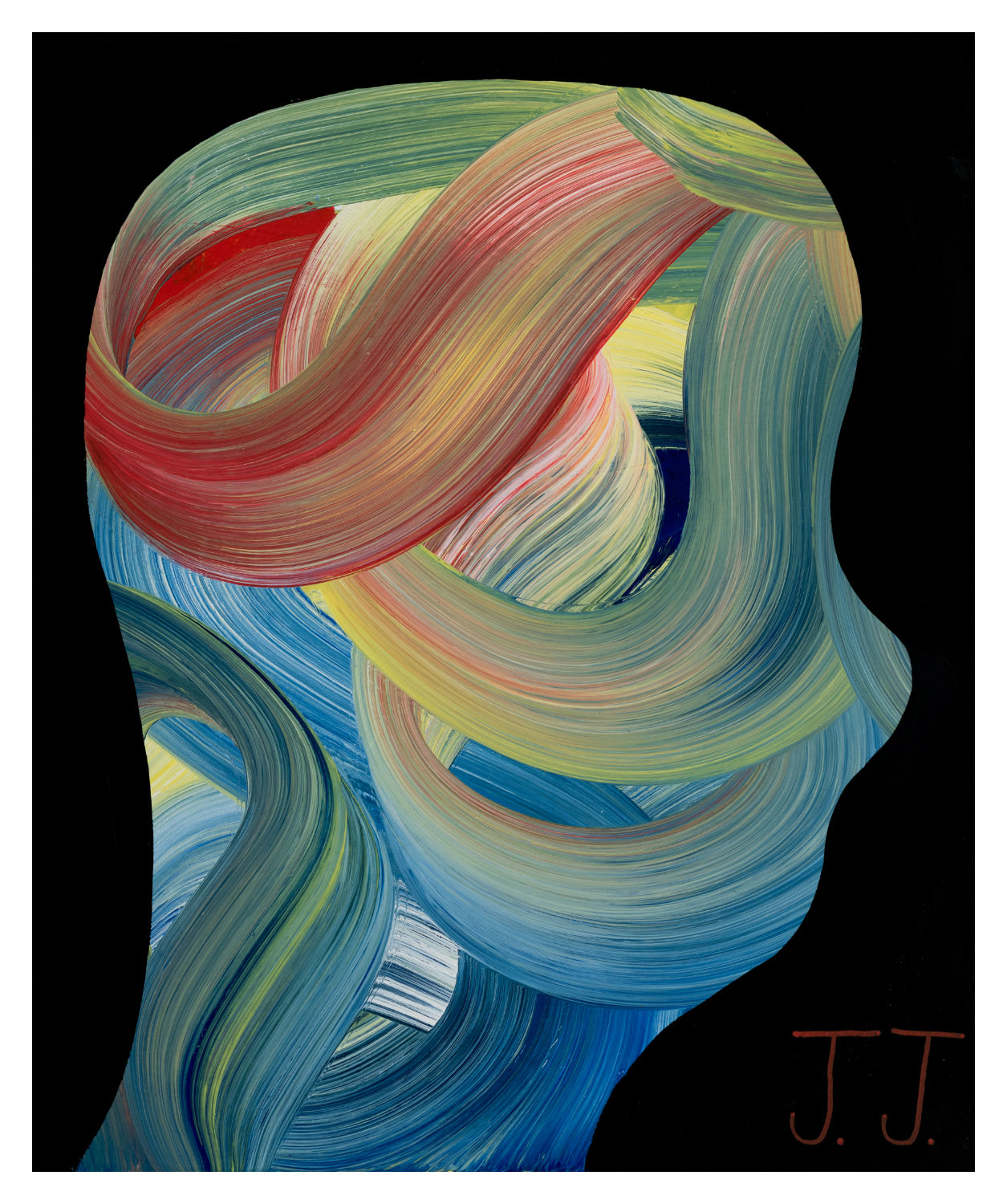

No. There are things happening in my paintings now that are becoming optically weird. I was doing a hair gesture that’s red with blues on top, and it does this vibrating thing, if you know what I mean. It makes your eyes water. My wife said it hurts her eyes. But when you take a photo, it somehow evens out through the camera and you can’t capture it. It’s like a living thing. Sometimes I’ve done that intentionally, but that’s more of an optical trick, not a color trick. It just happens because of how our eyes read the color. In general, I’m more of an intuitive worker. I do what’s working and strive for what that is.

How does your son influence your art?

Kind of majorly. For me, it’s all about time. Time became so finite that I have to be very economical. I have a day job, and then I come home and we have dinner, and then we do the dance, read the book and all that stuff. I don’t get to the studio until 8:00 p.m. and I only have a couple hours. It’s made me more motivated, the less time I have, ironically, and I work well that way. I’ve actually used drawings my son made and cut them up and sold a couple collages that had his hand in them.

What’s your balance between painting and collage lately?

I work concurrently. I’ll be painting, and while things are drying, I’ll move over to my table and work with collage. It’s a constant back-and-forth. My paint of choice for collage is mostly gouache. I love the chalky flatness. And my other primary thing is sumi ink, which is my favorite. And I have a weird paper fetish. There’s a certain type of paper I use to create this kind of blotted effect, and it’s hard to find.

What is it?

I’m not going to tell you.

We have ways of finding out. How do you describe the kind of brushstrokes you do? At first I thought they were prints.

Oh, good. I just got a message from a master printer in Philadelphia asking if I wanted to make lithography prints, and I was flattered. I did printmaking in school, so that’s probably why I lean toward the printmaking aesthetic.

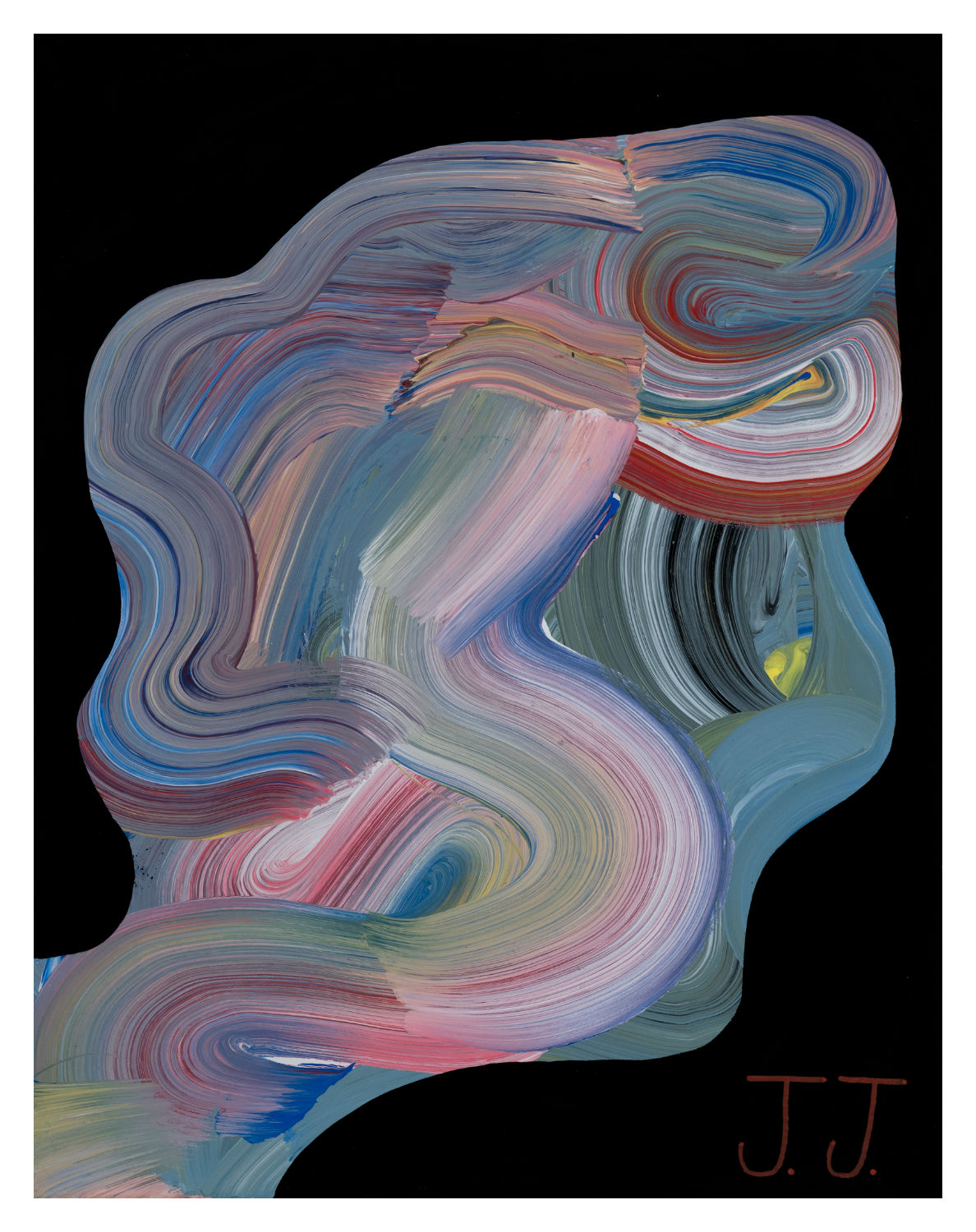

Lately, with painting, it comes down to this immediacy. There’s a certain thing about the artists I love—it looks spontaneous but there’s a certain amount of confidence and directness. There’s no bullshit. There’s no fat. That directness is really a turn-on for me. There’s something important in that energy. People respond to it.

Immediacy can be a difficult concept to grasp, but it’s about the risk factor and how many practice strokes it took you to make those really great ones very quickly.

There’s a great adage about someone asking Picasso, when he was in his late seventies and doing primitive stuff, how long it took him to do it because it looked like a child’s work. And he said, “It took me 50 years to paint like this.” It might be really quick, but you do it thousands of times.

With drawing and collage, there’s less risk. With painting, you have to stretch the canvas and gesso and prime it, and it’s so precious; but with drawings and collage, you can jump off the diving board and get right into it. I’ve been trying to do that with my paintings lately, and it’s difficult. Painting does what it wants and you have to bow. I’ve only been painting for about four years now, and it’s hard. It’s really hard.

You are kicking ass for having only been painting for a relatively short time.

I really work all the time. I used to play a lot of chess and I play the saxophone, but I’ve kind of fallen off of that because, with anything worthwhile, you have to do it all the time. I think I read that Charlie Parker put in 15 thousand hours before he was 25. That’s insane! That’s probably what master surgeons have to do. You just have to do it all the time and own it, and that’s what great artists are like. They just own it, and if you own it, you’re in. Not “in” with regards to success, but just being an artist’s artist.

How come you never painted until recently?

I did tons of collage and I made a choice. I was missing my hand in the work, and the immediacy we talked about earlier. Collage is still important to my work, but I decided to just draw for a year. I had 180 drawings by the end, so I decided to cut up the ones I wasn’t going to frame, and I started collaging with them. It got me loose and warmed up and let my language really develop.

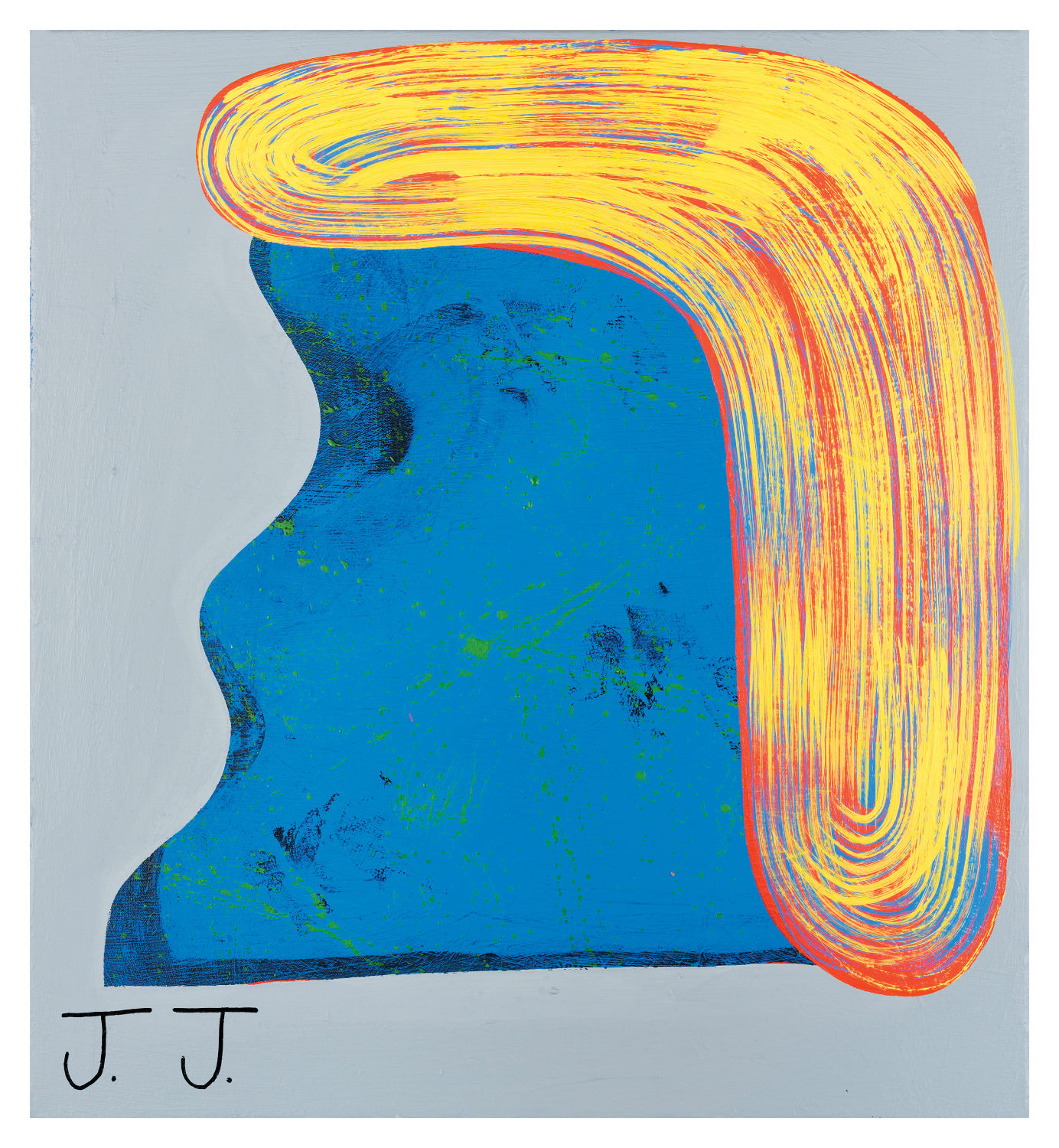

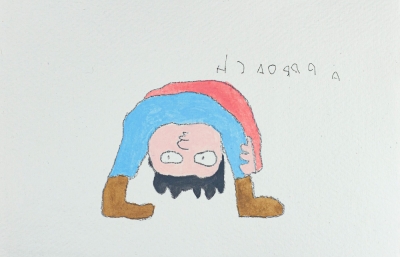

Tell me more about your paintings of heads. Are they a series?

It’s a tired thing. Everyone does it. Look at the masters, someone like Donald Baechler. He’s on Instagram. At first I liked the heads as a vehicle to explore. I started painting, and I knew it was going to be a head, but I didn’t know how to do the hair. It was a starting point, a structure I could riff on and develop approaches and certain intentions. Eventually, I got tired of it and was trying to branch out to do some more abstract stuff, but they just keep coming back, and I realize I shouldn’t change things if it’s working for me. I want to be an abstract painter, but then I think I should just do what I do, and do it well.

To me, you’re right on the border of abstraction.

There’s a fine line. A lot of people paint heads. It’s classic. I’m glad I’m on the cusp. I want to be more abstract, but some things just happen. It slingshots back to a face. Sometimes I’ll be creating something, and I’ll leave it abstract, but then I’ll put a hairdo and drop an eye on it, and it looks lovely.

What’s with the J.J. signature?

I know, I know. I made prints at Gallery 16, and Griff Williams said I had to sign them, and I didn’t want to, and he said “You made the J.J. a thing,” and I kinda did. And I like it because I own it. It’s about that confidence and stamping it as mine. If I had different initials, maybe I wouldn’t do it, but J.J. kind of works. In some of the paintings I’ve done recently, it doesn’t fit, and in the back of my head, I’m like, “You better put it there!” In fact, I sold a painting to a guy and he was, like, “Uh, it doesn’t have a J.J. on it.” I put myself in a corner where I have to do it all the time.

I like that it’s so big. It’s kind of comical.

What it does for me is it brings it down to earth, like OK, it’s a painting. It’s not going to change the world right now. Take it easy.

What’s the value for you in looking back at art history?

Just to see the cyclical nature of everything. Nothing really changes. That sounds like bullshit, but for example, Ellsworth Kelly died recently, and there are so many people painting like him right now. Everything comes back around. There’s so much history to learn and so many artists out there. It’s insane.

I was recently thinking about that, how there are millions of artists in the world, and so few become known.

Right. For every artist you know, there’s ten or twenty that you’d never know. For every Coltrane, there’s probably five other guys that play just like him, you just never heard about them.

----

This is an excerpt from the May, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz, on newsstands worldwide and in our webstore.