Anyone reading this cleaves to the belief that art and culture have the power to directly change the world, and Migrate Art chooses to take extra steps that actively inspire us all to address and galvanize engagement with the humanitarian issues of our time. We have proven that it is possible to blend the worlds of art and charity to create a hopeful, motivating force, though indeed, these two worlds have their own inherent limits and restrictions.

Art often speaks about political and social issues but neglects to reciprocate those sources of inspiration, resulting in a lopsided beneficiary. I have often seen successful western artists motivated by humanitarian needs without paying demonstrable dues to recompense their source of motivation. With extra consideration, it is possible for art to complete the journey and bridge the gap between the people who initially inspired the work and the compensation that comes from the final sale.

Charity, however, can be mired in mistrust, and is often referred to as “the third sector,” as if the normal rules of business do not apply. This attitude is extremely limiting, and we have found ourselves in a situation where many charities are opaque, dull and uninspiring. By focusing on creativity and united art, charity and entrepreneurism, Migrate Art has successfully developed a more interactive partnership where charitable organisations maintain creativity and excitement, spurring connection, instead of simply soliciting a $10 donation monthly. As of 2020, there are over 80 million displaced people in the world, that is, 1% of the world’s population doesn’t have a place to call home. Creative art allows us to raise money and also share these folks’ stories, which in turn, creates compassion and empathy with others all over the world.

In 2016, I first visited the Calais Jungle refugee camp in France, a makeshift campsite on the edge of Calais that was home to almost 10,000 displaced people. An infamous patch of land, UK media was full of stories about “swarms of migrants” trying to reach Britain. As someone skeptical of what appeared in the news, I decided to go and visit the camp myself. I saw a very different side, a home to people from all over the globe, from Iran to South Sudan, and despite dreadful living conditions, a site rich in culture. Cafes, a school, a church and theatre existed within a place of transience, people arriving or leaving every day, resulting in an incomparably unique environment. The warmth of the people I met was a stark contrast to the unfriendliness of many people back in London who had every convenience. I decided to find a way to bridge these two worlds, using my experience and contacts in the art world to help the people in Calais.

A few months later, I returned after “The Jungle” had been demolished by the French authorities, discovering a number of colouring pencils in the dirt where the makeshift school had stood. There was something powerful about these pencils and crayons—they chronicled a temporary town that no longer existed. I rummaged through the debris, collected the pencils and brought them back to London, intending to send them to artists to raise money and awareness for the millions of people impacted by this crisis.

The big challenge was to animate the world’s best artists to empathise and participate with our cause. The artists seem to connect with our projects on many different levels. Some completely align with the mission, offering utmost collaboration; others express kinship with the creative ideas behind our projects, and many simply want to do something to help but don’t know how.

Many artists do reflect their own lives through our projects—Loie Hollowell and Conor Harrington saw parallels between the children in the refugee camps and their own young families. Raqib Shaw and Mona Hatoum both arrived in London as immigrants, and related their own stories to the people I had met in the camps. Some artists have direct connections, like Sara Shamma, who fled Syria at the start of the Syrian conflict, Iraqi artist Walid Siti, who left his homeland in 1984 to escape the Iraq-Iran war, and Burmese artist Richie Htet who recently moved from Burma to Paris to escape imprisonment by the military dictatorship.

The artists we work with are asked for charitable donations on a daily basis, so Migrate Art has to stand out. Instead of sending emails, I often locate artist studios and send them something physical to create a direct connection to the story, for example, my “stalking” of Anish Kapoor. I knew his studio had been designed by a famous architect and noticed a tiny, pixelated street name on his website. After Googling that street and finding his studio, I went in person with a handwritten note and one of the pencils from Calais. It worked. He has since been involved in two of our projects, and we are about to release a new edition with him.

After a year of relentlessly working on our first project, I gathered 33 brand new artworks from amazing artists, including Sean Scully, Rachel Whiteread, Jeremy Deller, Pejac and more, all of whom used the pencils from Calais. We curated an exhibition in Mayfair in London, culminating in an auction at Phillips in London, raising over $175,000 for our charity partners. We met people who visited to see work by their favourite artist and then learned more about the wider context of the project; other visitors had previously volunteered in Calais and wanted to continue to support the cause. Most surprisingly, we met big collectors who loved the idea of buying art and doing some good at the same time. People were connecting with our message, and a community was forming.

In June, 2019, I was invited by one of the charities to travel to Kurdistan in Northern Iraq, which has been a war zone for most of my life. I wanted to see where the money we raised was being spent, curious to discover if this environment could lead to a lightbulb moment for a new project. I boarded a flight to Erbil, one of the oldest, continuously inhabited places in the world, and what followed for the next ten days was the most profound experience of my life. We visited several camps of over 50,000 people, primarily from Iraq and Syria, and were once again met with warmth and endless kindness. Whilst in the camps, I held art classes with groups of children, and was struck by the dark nature of some of the drawings. Teenagers were drawing skulls, villages on fire and airstrikes, which lent frightening insight into the intensity of their youthful experiences.

Driving through the countryside, I was struck by a series of vast, black, burnt crop fields, and began to ask questions about their origins. After conversing with locals, many theorized that the fires were caused by remaining ISIS fighters trying to intimidate local communities and demonstrate their presence in the region. I somehow knew if I could get this ash back to London, we could turn it into paint.

I got to work in 43-degree heat and started filling containers with this ash. Most people said I was a lunatic and there was no chance I would get it back through customs, but after someone commented that it looked vaguely like tea, I hatched a plan. I took a visit to the local market and bought tins of loose leaf tea. I removed the tea, replaced it with ash and resealed the tins as best I could. Miraculously, two days later, I was standing in Heathrow airport looking at the tins in my bag—they had made it through.

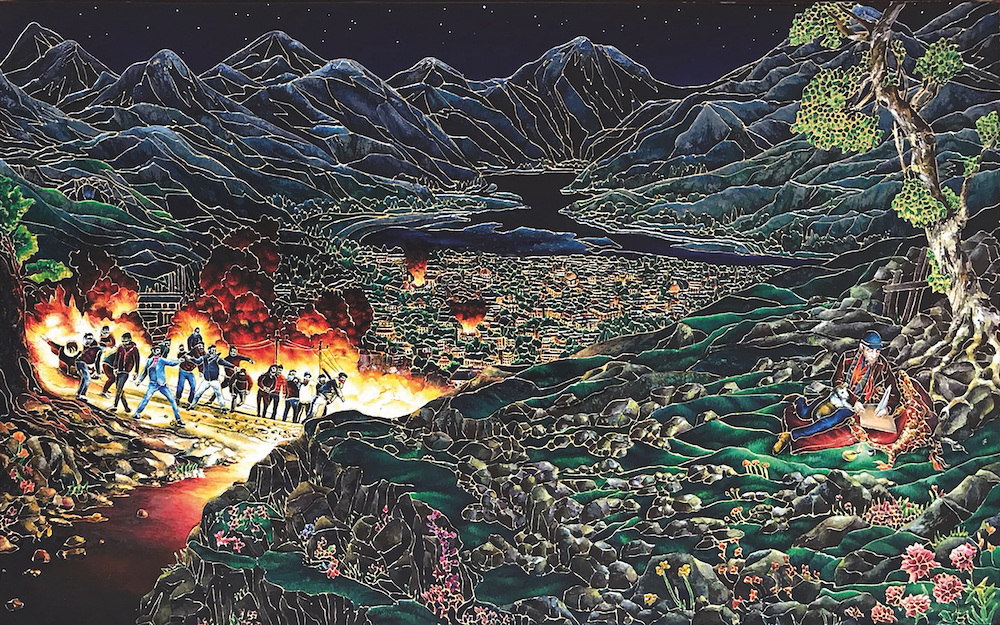

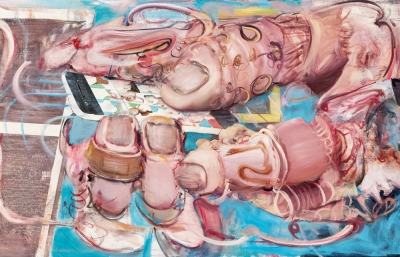

After more cold calling, we formed a partnership with Jackson’s Art Supplies, who offered to take the ash and make bespoke acrylic and oil paints. After some more detective work, I grew a list of incredible artists all eager to create something with the paint. In October, 2020, we hosted Scorched Earth, an exhibition of 15 incredible, original artworks from the likes of Loie Hollowell, Jules de Balincourt, Mona Hatoum, Antony Gormley and Richard Long, and also produced two brand new print editions with Shepard Fairey, all made with our Scorched Earth paint. Alongside works by these artists, we also showed a series of drawings by children in the camps in Kurdistan, which connected on a deeper level with the hundreds of visitors to the show. We later auctioned the works with Christie’s and raised over $475,000.

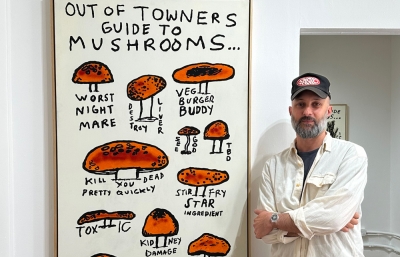

The approach we have developed means we can react to humanitarian issues as they arise, raising much needed funds for urgent issues as they happen. In 2020 we launched Masks for Meals, a series of artist-designed face masks that raised over $60,000 to feed the UK’s homeless throughout the Coronavirus pandemic. And, most recently, we curated Raising for Myanmar, a series of 20 limited-edition posters by leading artists including Jeremy Deller, Sarah Lucas, Sean Scully and Chloe Early to raise money for Mutual Aid Myanmar to help supply food, shelter and healthcare to communities suffering at the hands of Burma’s violent military coup. The project ran for 6 weeks and raised almost $40,000.

Art is a force that can change the world, and isn’t just about auction records, inflated markets and champagne receptions. There is a reason we all chose to get involved in the art world, and for 99% of us, it is because art speaks to us on a deeper level—the rest is secondary. Art has the power to transform and become a catalyst for meaningful progress. For the Migrate Art team and me, this is the bedrock strength of art and culture. —Simon Butler

Simon Butler is the founder and director of Migrate Art, and is based in London.