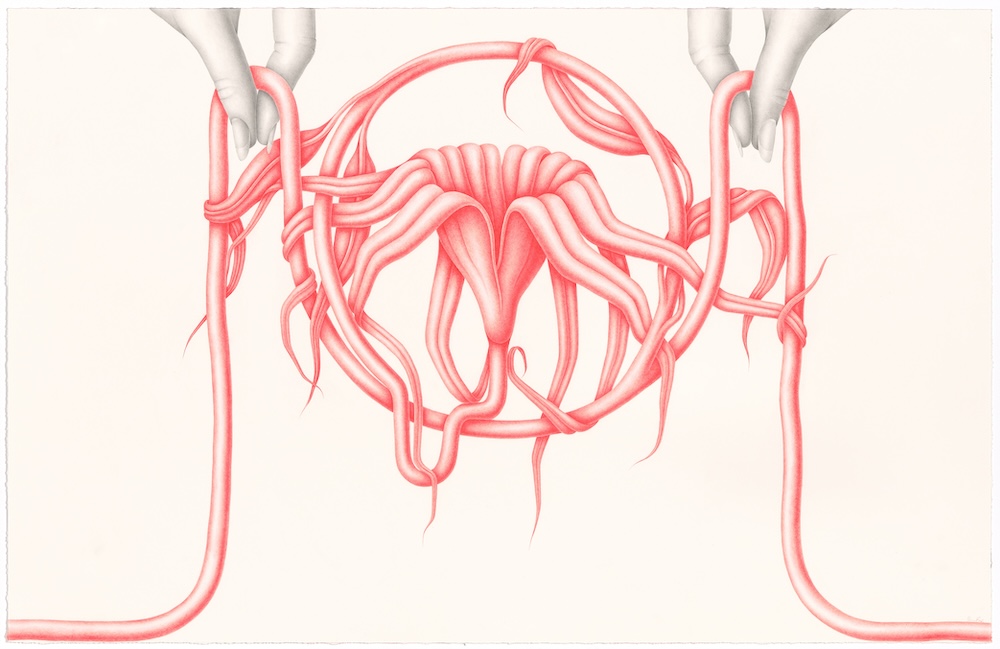

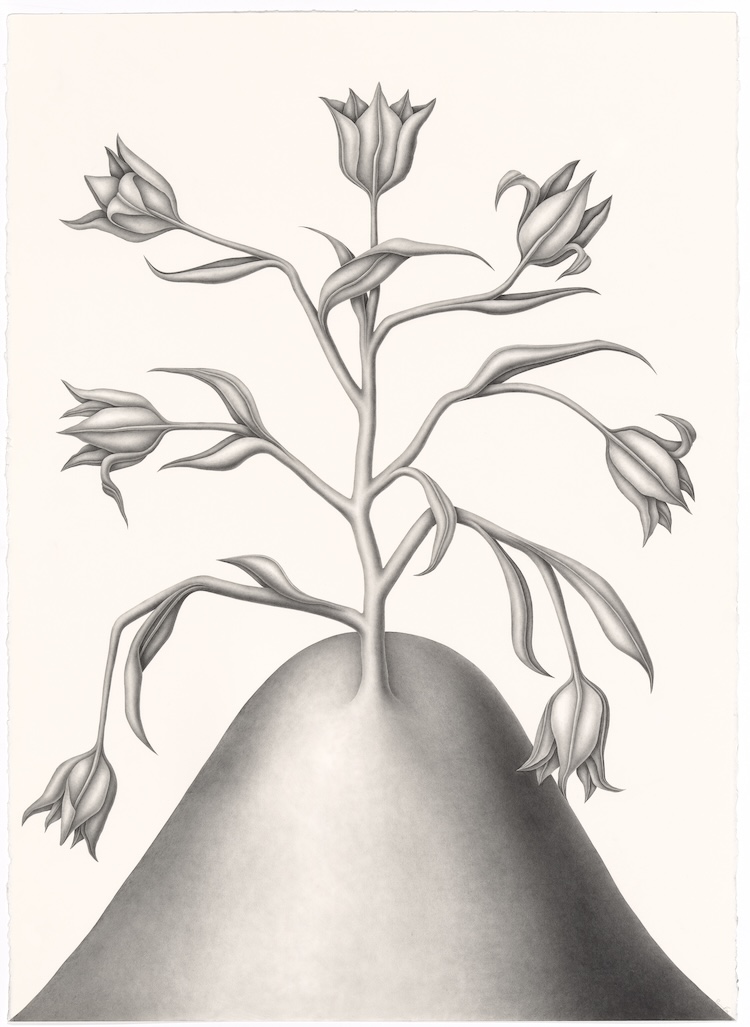

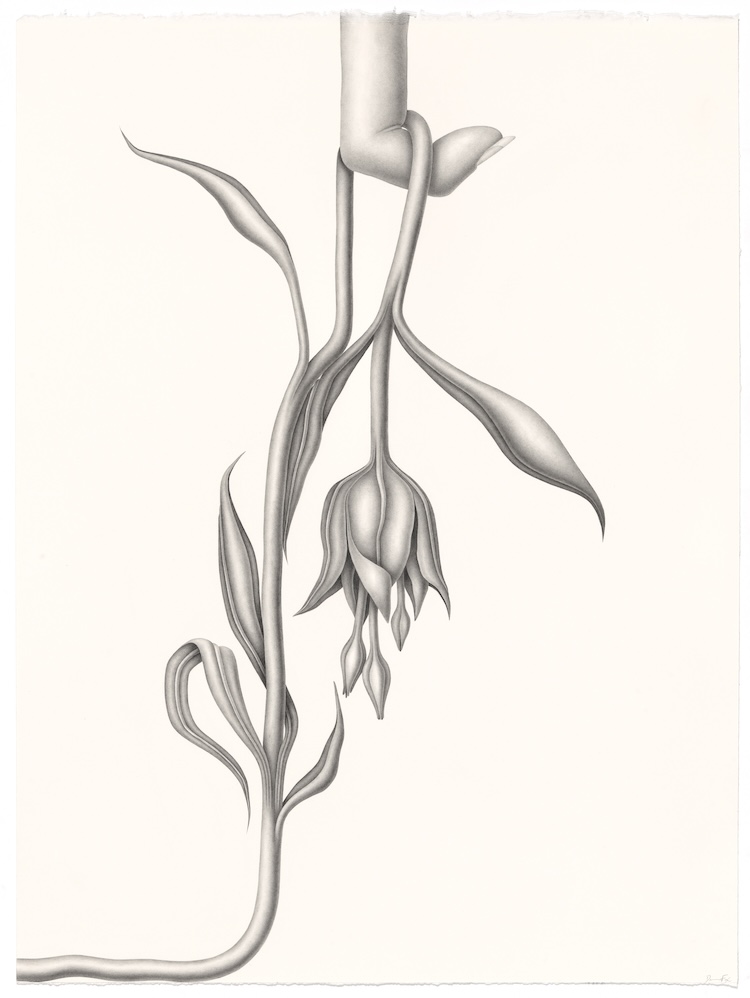

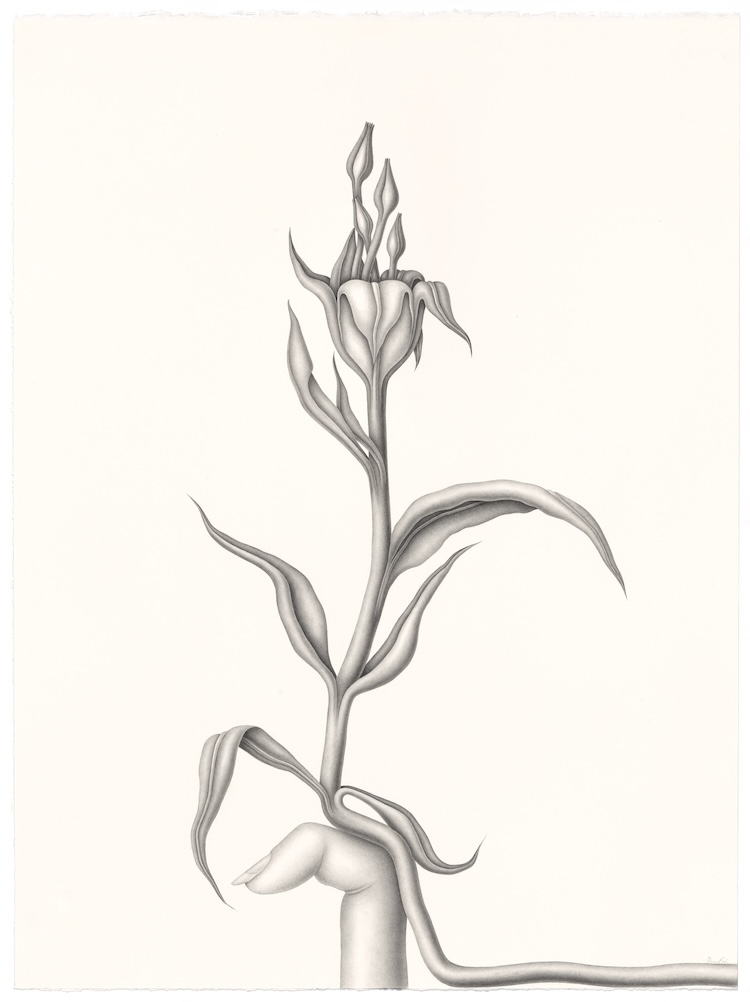

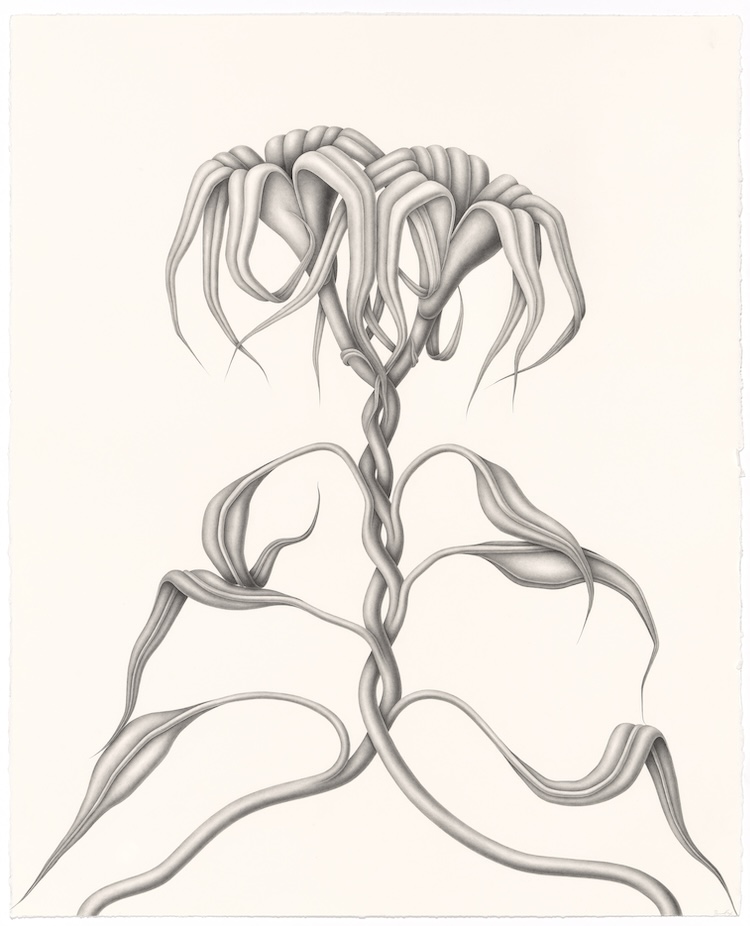

Creating a new life from the materials of our bodies may seem like something only a god (or mad scientist) would attempt, but pregnant women do it everyday. Half of the world’s population is biologically equipped to grow a new person; to create a being in their image. A new mother herself, artist Devra Fox doesn’t put science fiction aside in her drawings, instead relating her experiences to the life cycles of plants. Taking on quite surreal qualities through their large bulbous openings and long, languide stems, Fox’s drawings acknowledge that the new sensations and transformations of pregnancy can feel strange, but ultimately they are a part of the natural cycle.

Before the opening of her solo exhibition In Orbit at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco, Fox spoke with the gallery’s Katherine Hamilton about the inspiration behind these works, her long-term thinking on bodies as vessels, and how power, control, and grief factor into these works.

Katherine Hamilton: Over the years, your graphite drawings have explored ideas of containment through surreal representations of flora. Did you explore anything different for this body of work?

Devra Fox: I started working on these pieces in the fall of ‘23, in my second trimester of pregnancy, so the baby was very much on my mind! The idea of containment is always present in my work and being pregnant deepened and altered how I think and feel about it. Growing a human is a surreal experience. This body of work was my way of finding a sense of grounding within the pregnancy while animating my own bodily experiences.

What was most often on your mind while drawing?

It is fascinating to me that my body innately knew exactly what to do to grow a human without any kind of intervention or instruction. This thought—the inherent knowledge that is present in my own body and the natural world at large—kept coming to mind while creating these drawings. Unobstructed nature is perfect in its own cycling of growth and decay, containing an indisputable knowledge. I was comforted by these ideas because there are so many pitfalls of doubt and “shoulds” that are put on a pregnant body. In Orbit, is my exploration of two bodies growing and orienting themselves to each other, creating a new sphere of dependence and trust.

These works are also a bit more uteral in shape and composition than previous works. While the work in 2021-2022 had these creaturely features (long willowy limbs like centipedes or large, bulbous petals like swollen fingers), it seems that you’re gravitating towards flowering bodies with large openings, and long, languide stems like fallopian tubes.

I’ve always been interested in the physicality of bodies and our internal structures. The concept of how our bodies act as literal vessels is a constant in my work, which shifts focus depending on current interests or personal developments. I’m fascinated by the bizarre functionality of our internal spaces. When I started thinking about getting pregnant, I wanted to see how it all functioned—these shapes inevitably made their way into my drawings. I find these uteral, umbilical, womb-y structures beautiful in their abilities and form. I’m always interested in the parallels that exist in nature and our own bodies, the branches of a tree and the veins in our bodies for example. I use these parallels to connect the domains of body and flora, highlighting this inextricable relationship.

I’m also curious, do you have a lot of plants?

I do, I love my plants! I have to restrain myself when I go to a garden store.

Beyond the uteral allusions, something about the delicateness or the tenderness used to make these languid, nimble plant-creatures feels feminine. Would you characterize your work as feminine? Push against such a classification?

I’d say they are feminine, as they are made by my own female identifying body and are speaking to mechanisms within that. There is a softness that I hope is apparent in the drawn relationships, an organic melding of individual to group and a feeling of dependence upon a larger system. At the same time, I don’t think softness or interdependence are gender specific.

Writers often cite that your work deals with relationships of power and powerlessness, control and that which is uncontrollable. When are you most in control and when are you most powerless?

Power or control and the inverse, for me, are held simultaneously in the body. I feel control in how I move and create and what I am able to produce as an artist. I lost my mother to cancer when I was 19 years old and it left me with a deep sense of powerlessness to the natural world. As much as I would like to try to possess a sense of control, life is fragile and can change on a dime. Nature decays and changes in terms that are beyond intervention. I guess my biggest challenge is letting go of “control” and trusting things to unfold as they should.

That’s interesting. I was wondering because I would imagine that, to make these drawings, you must exercise a lot of control. In what ways do you relinquish control in your practice? How might you lean into being or feeling powerless?

Part of why I am so attracted to drawing is the process itself. It is slow, meticulous, time consuming and not easy to manipulate—in a sense, very controlled. In the cyclical process of drawing, blending, erasing over and over again there is a meditative quality. I find the repetition soothing, allowing a calmer state to emerge and a sense of release, a softening of control. I realize this isn’t necessarily apparent in the technique itself but in the state of making this is what happens.

I also want to talk about the lack of context in these works. Save for the occasional hill or mound, these plant figures appear to be nowhere, almost completely void of context. Can you expand on this shift in how you represent these figures?

When I am creating my drawings they take shape as an individual or grouping of forms, as internal sentiments animated in space. I envision them in position or action with themselves or each other. I am more interested in these relationships than getting caught up in creating a context that isn’t initially present. In this sense, the spatial ambiguity is another way of releasing control, allowing the viewer to muse over the context or larger environment of the drawing.

I also wonder about grief in these pieces. You mentioned in an interview last year that your mother’s passing sparked an idea about the containment of a person through something tangible, like a drawing. I think of grief as the inverse of joy, in that, to grieve something you must miss it; it’s another tendril of love.

Grief is something I live with daily, as anyone who has lost a loved one knows. The Buddhist concept that you can’t know joy without suffering resonates with me and mirrors what you’re speaking to in the question. I explore this duality often in my work as I think about the cycles of life and death, growth and decay, you can’t have one without the other. Like the Nascent drawings, these opposites often appear in my work through inverse relationships, light and dark, above and below, left and right. It is a way of representing the duality of life and how one state cannot exist without the other, creating an inherent dependence or balance that I often feel compelled to represent.

In Orbit is on view through April 27th at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco. Installation images were taken by Shaun Roberts, opening night images were taken by Kuan Ya Wu.