Love is the axis around which Poulomi Basu’s practice turns—often so fast and fervent it becomes blurred. Without love, it would be impossible to look so deeply at such unspeakable violence and chaos, as Basu has done, turning the lens on her own trauma, as well as those felt collectively by women in the personal, private and domestic spheres, and on the frontlines of conflict and eco-disaster.

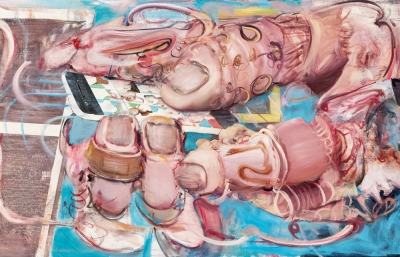

Every element has its opposite. In Basu’s static and moving images, we are submerged into a world like Plato’s realm of forms: shadows, burning fires, painted bodies, veils, and hybrid forms creating a tense atmosphere, remixing documentary materials Basu collects in often dangerous environments with ideas drawn from the Science Fiction novels of Octavia Butler or films by Jonathan Glazer. The protagonists in this shifting alternative universe, however, are always the South Asian women whose “bodies are sites of political warfare” in a patriarchal world—women who have been systematically silenced and subjected to violence but survive. “We are the monsters and the goddess,” says Poulomi, “we are magic and the curse—I like that sort of tension, that even within a violent space there is a beauty, and within a beautiful space, there is darkness.”

In the series, Sisters of the Moon (2022), Basu appears in an eco-feminist tale, bathed in ethereal light, the central, Cyborgian character in a dystopian near future. This speculative language that has been steadily evolving in Basu’s practice over the years finds complex new expressions in Fireflies (2019-2021), a body of photographs and films presented at Basu’s solo exhibition at Autograph, London earlier this year. In the photographs, Basu appears, sometimes with her mother—both survivors of domestic abuse. The work deals with their intertwined, intergenerational trauma, returning bodies to the land to heal. “I wrote myself in these various landscapes where you see me embedded close to earth because I do believe that the deep, divine, feminine energy existed even beyond patriarchal times, and the male is born out of the woman. There was a matriarchal society and world before it was destroyed.”

Given the ongoing trauma and oppression facing women, particularly women of color, inherent in the past and endemic in the present, the future becomes the only viable space in which to imagine ourselves. Sisterhood, solidarity, and soaring empathy pour forth in Basu’s works. And they have made a difference: an early breakthrough work, Blood Speaks: A Ritual of Exile (2013-2016), on the perilous ritual practice of Chhaupadi in Nepal, where women experiencing menstrual or postpartum bleeding are banished from their communities to live in unsafe and unsanitary shelters, resulted in a change in legislation. “When I was growing up, I really felt like I had no power. So for me, the work became about subverting and destroying those power relations.”

Yet bound up in Basu’s destruction is an act of creation—the creation of a space for love. As Arundhati Roy once wrote; “another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.” —Charlotte Jansen from the Fall 2022 Quarterly