Ruth Asawa once said, "When you put a seed in the ground, it doesn’t stop growing after eight hours. It keeps going every minute that it’s in the earth. We, too, need to keep growing every moment of every day that we are on earth." She learned to draw in an internment camp during the War and was later mentored by visionaries like Josef Albers and Buckminster Fuller at Black Mountain College. Her keen eye and appreciation for craft during travels in Mexico inspired the looped wire sculptures that the New York Times described as “magic lanterns.” She drew, painted and sculpted, often surrounded by her six children, and I was fortunate to have a chance to interview two of her daughters, Aiko Cuneo and Addie Lanier.

Gwynned Vitello: I think many of us know that your mother learned to draw in an internment camp for Japanese-Americans, but can you paint a clearer picture of this childhood? What kind of education did these children get? Was she naturally inclined to make drawings on her own?

Aiko Cuneo and Addie Lanier: Ruth Asawa began to be recognized as a talented artist when she was in third grade at her public elementary school in Norwalk, California. By the time she was 10 years old, she thought she wanted to be an artist. Her older cousin, Henry, was a very talented artist, but drowned tragically as a teenager. Perhaps his death played a role in her decision.

Santa Anita Racetrack was the first assembly center her family was sent to before being moved to permanent camps. She was 16 years old and got to study with Disney artist/animators Chris Ishii and Tom Okamoto, who were also interned. Given a choice between weaving camouflage netting for the war effort to earn a little money, or take makeshift art classes set up in the bleachers at Santa Anita, she opted to study with the animators. She was there with her mother and five siblings, plus her aunt and cousins for about six months before they were shipped by train to Rohwer, Arkansas.

At Rohwer, Ruth studied with Ms. Jamison, an art teacher, and Mrs. Beasley, an English teacher, who took some of the art students outside of camp to sketch and paint. We have two paintings that she did while interned, one of a sumo wrestling match, the other a landscape of a swamp.

How did she get the opportunity to travel to Mexico, and how did that trip influence her art career?

She took two trips to Mexico. The first was a study trip to Mexico City in the summer of 1945 with her older sister, Lois. Ruth studied art with the designer Clarita Porset and Lois studied Spanish. The second trip was in 1947, when Ruth was part of a group of students sponsored by the Quakers to go work as interns and teachers in Mexico, and she was joined by her sister, Chiyo. For the second trip, she spent most of the time in Toluca, Mexico, teaching art to children, which is where she learned the wire looping technique from a local craftsman. He showed her how they made egg baskets out of looped wire. That same year, Josef and Anni Albers had taken a sabbatical in Mexico and she met up with them in Mexico City, where she saw Diego Rivera painting murals and was able to see his home in Coyoacán.

What led to her enrollment at Black Mountain College? How amazing that she studied with the likes of Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg!

While Ruth was enrolled in Milwaukee State Teacher’s College, she had two friends, Elaine Schmitt and Ray Johnson, who had both gone to Black Mountain and encouraged her to take Josef Albers' design class in the summer of 1946. Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham all came as visiting teachers in the summer of 1948. Both Asawa and our father Albert Lanier (whom she met at Black Mountain) were there for that summer. It was magical.

Did she have mentors, or did she just decide to pursue art in her own way?

Black Mountain College gave her the mentoring of two phenomenal minds (Albers for design, how to see the world and live as an artist; Fuller for his optimistic, individual experimenter of the universe outlook). She was also exposed to strong, independent female artists, such as Anni Albers, M.C. Richards, and Charlotte Schlessinger. Both Ted Dreier, one of the founders, and Josef Albers advocated for her to return to Black Mountain College in the fall of 1948 (against her parents’ wishes) so that she would become an artist. This extra year with Josef Albers was critical as Black Mountain gave her the courage and confidence to separate from her family and become an artist.

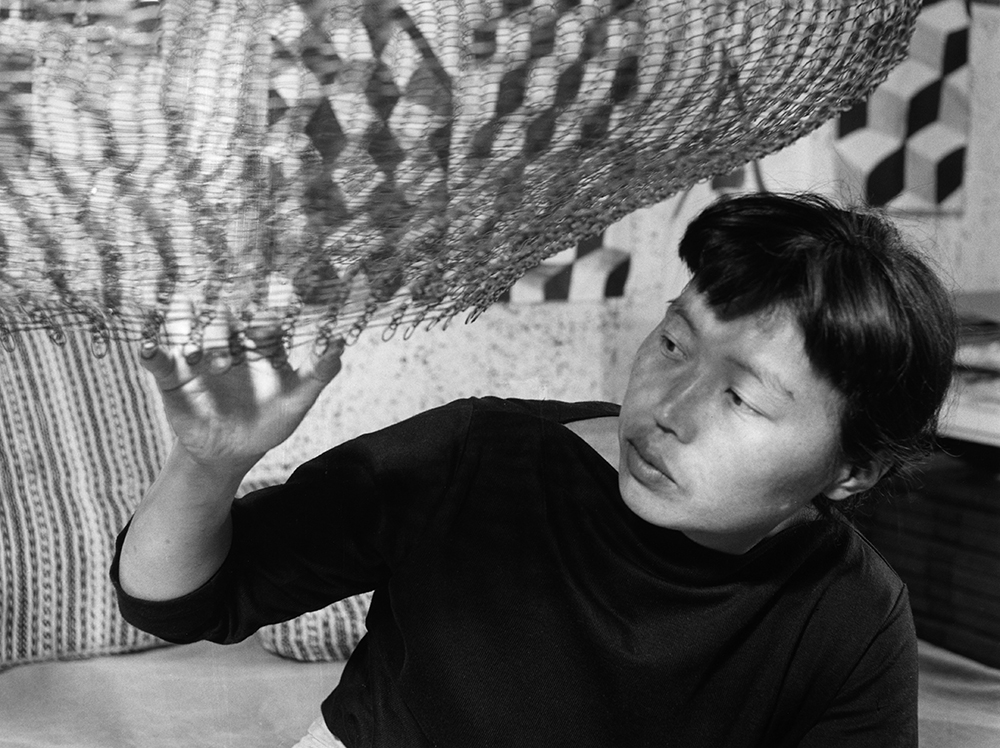

Can you describe her process for creating the crochet wire sculptures? How long did it take to make them, and did she work alone?

She said, it took a "lifetime" to make them. In terms of time, it could take her anywhere from a few hours to months to make a sculpture, depending on the complexity and ideas she was working on. For her looped forms, she rarely sketched them first. In some instances, if she was being commissioned, she would draw prospective forms, but they were very general ideas. Most often she made them, and then sketched or mapped them after the fact. Later in life, after she had developed her tied-wire forms, which often involved some basic mathematical calculations, we have evidence that she did some mapping of her looped forms, but this was long after she had mastered them. Sometimes we children helped her coil, but she always did the looping. She never had anyone assist her in the forming of her looped wire sculptures.

Did drawing and painting presage her sculptural works, and did she continue all three art forms throughout her life?

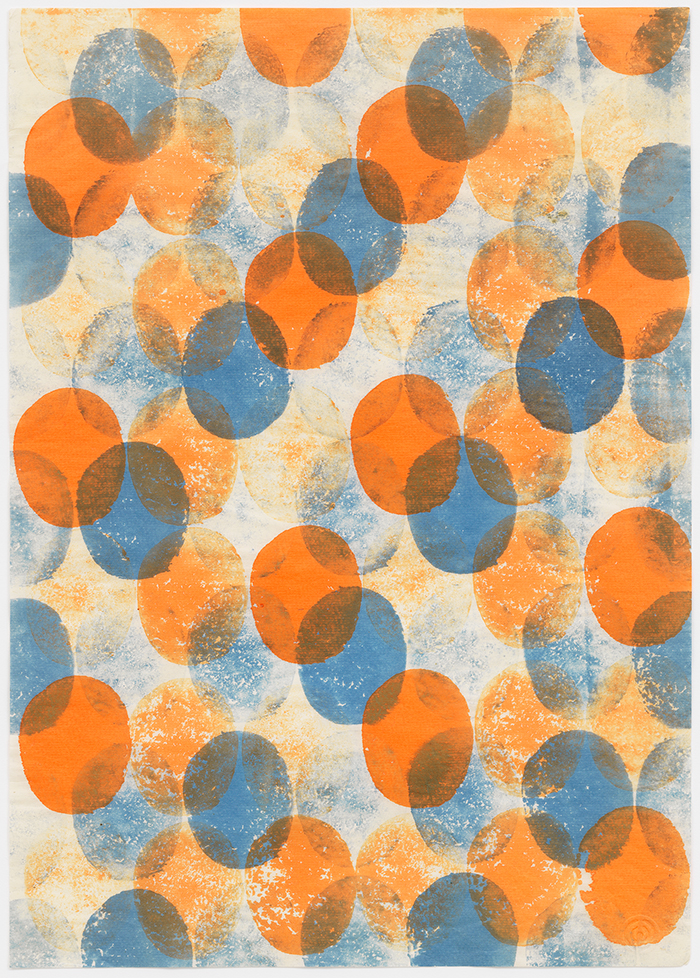

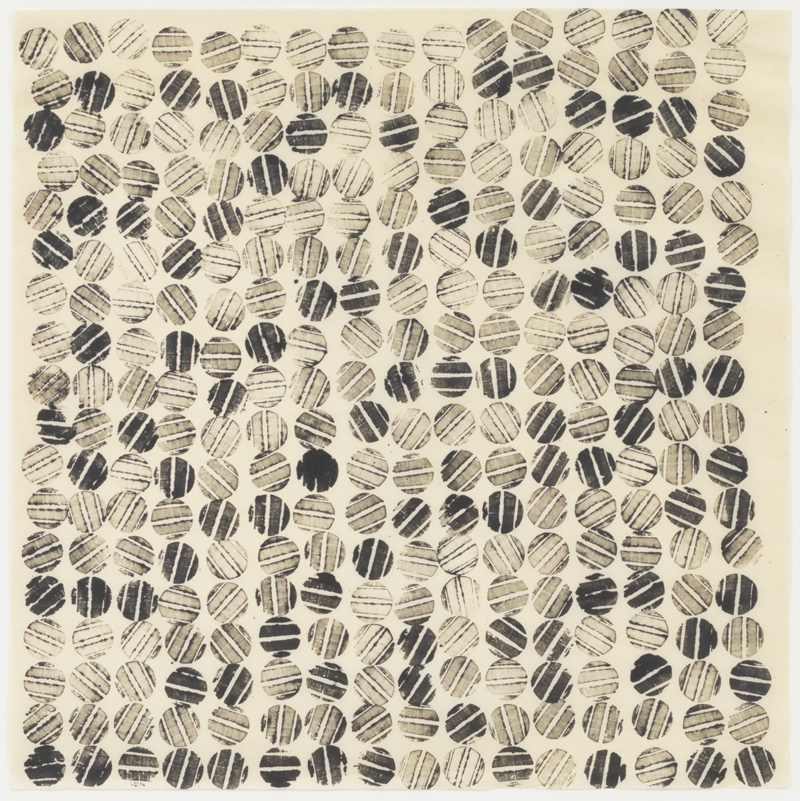

Her Black Mountain student work (1946-1949), which is two-dimensional, foreshadows her looped wire forms. She sketched almost everyday because it helped strengthen her ability to see.

She seemed ambivalent about the business aspects of making art. Did she work with a gallery early in her career, and did she have commercial success?

We have a letter she wrote in 1952 to Laverne Showrooms in New York. They had asked her to make a number of baskets for sale, and she told them, “I am interested in producing to sell, but the more I work, the more ideas I get and I want to experiment, but experimenting is not producing since there are always many flops.” She did have three shows at Louis Pollack’s Peridot Gallery in 1954, 1956, and 1958, but the distance from New York and her growing family in California made it difficult to maintain that relationship. By 1958, she had five children, and would have one more by the end of 1959. She had a few gallery shows in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, but was never comfortable with the business side of art. I think she resented the 40% cut that a gallery always got when they hadn't made the work.

Beginning in 1966, she made public commissions, which funded her large cast projects with assistants and collaborations with foundries and fabricators. She enjoyed these projects, both because of the chance to experiment with new processes and materials and the social community of making art with others. She was also paid a small salary. Occasionally, she sold works on paper or sculptures directly to collectors, who happened to meet her in the course of her arts activism or community life.

When did she start making public art? Is this how she became known as the Fountain Lady?

She began making public art with the commission in 1966 of Andrea, the mermaid fountain at Ghirardelli Square. Her friend and collector, Bill Roth, owned Ghirardelli Square and asked her to come up with an idea. Andrea was a neighborhood friend who had just given birth to a daughter at the time. Asawa would make three more public fountains in San Francisco (San Francisco Fountain–Hyatt Hotel on Union Square, Nihonmachi Origami Fountains–Buchanan Mall and Aurora–Bayside Plaza). The Garden of Remembrance, her last commission done in conjunction with landscape artists, includes a water element. In all honesty, the general public wouldn't recognize all the fountains as being by the same person because they are all so different. "Fountain Lady" may have been just one local reporter's appellation for her. What she loved about working on larger commissions was that she could collaborate and work with assistants, often her kids, friends, or other artists.

From what I read, it seems that she achieved her “personal best” as a middle-aged and older woman when she devoted herself to art education, especially instilling in children an appreciation for observation and making their own art. Would you agree?

Her career was long, broad in terms of the nature of work, and wide-ranging with regard to communities. Different aspects of her life serve as a hook for many depending on how their personal life and values resonate with her. For those who believe educating children is important, her activism in the schools is prominent. For those trying to juggle raising children with having an artistic career, her role as mother and artist takes precedence.

I think her private work was always the most important and the most fulfilling. This became particularly evident at the end of her life. She had the most intellectual energy, memory, and emotional interest in her personal work, as well as an unwavering confidence that her work was important, original, and worthy of recognition. But, at the same time, she felt that, as an artist, she had a responsibility to contribute and participate fully in her community. Given the chance, I don’t think she would have done it any other way

A new monograph, Ruth Asawa, was recently published by David Zwirner Books. Fifteen of her hanging sculptures are located in the entry to the observation tower at San Francisco’s de Young Museum.

www.davidzwirnerbooks.com

This interview was originally published in the Fall 2018 print edition of Juxtapoz Magazine