BLUM is pleased to present SZTUKĄ DIABŁA TŁUKĄ, Warsaw-based artist Agata Słowak’s first solo exhibition with the gallery. Alison M. Gingeras, curator and writer based in New York and Warsaw, sits down with Agata Słowak to discuss the influences and themes that have shaped her latest works.

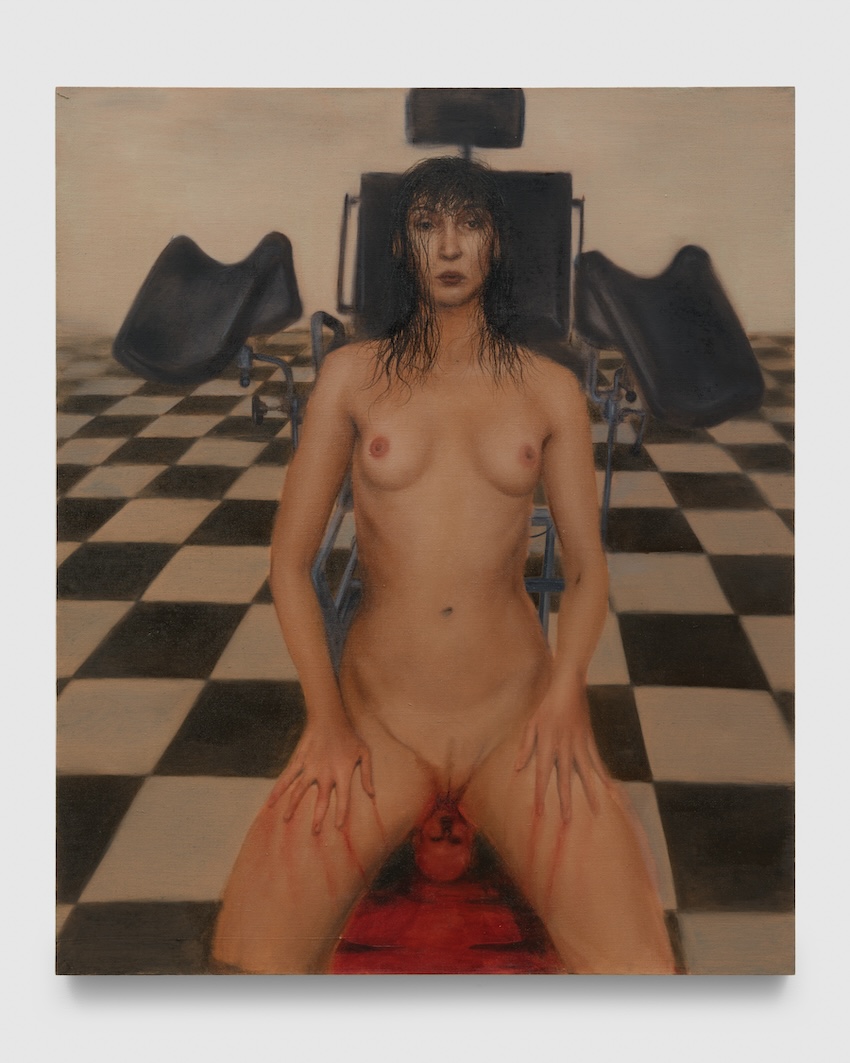

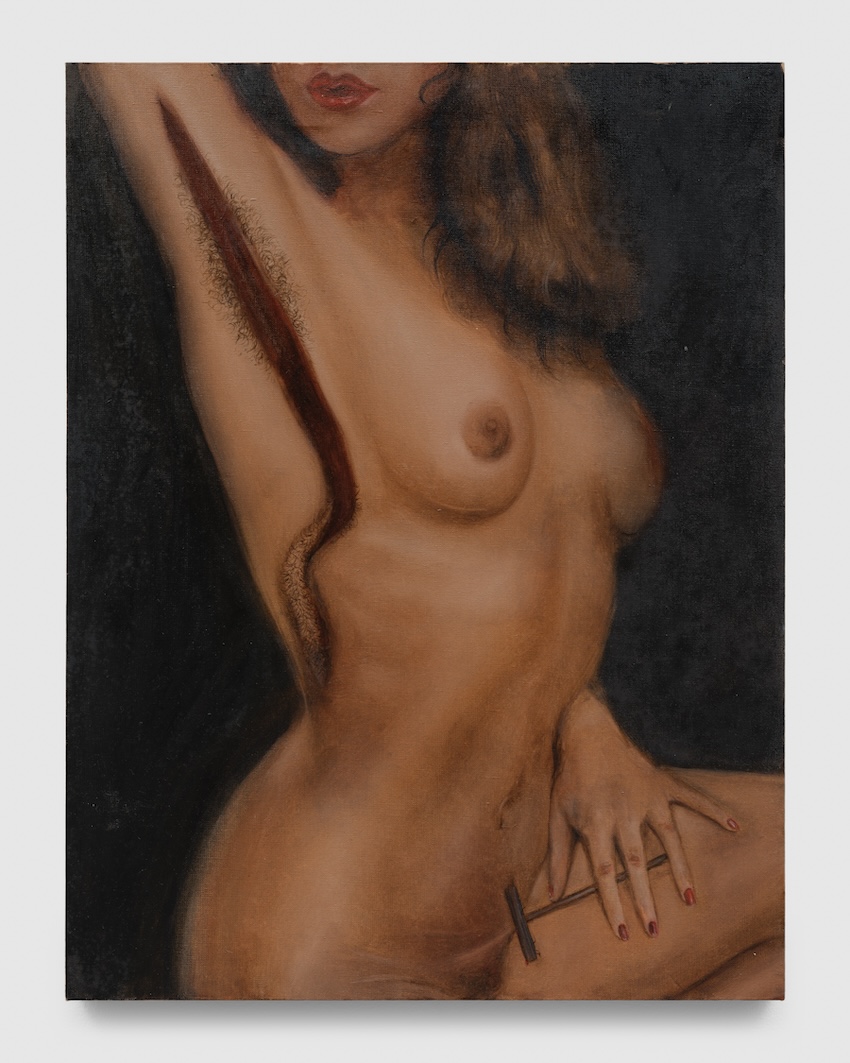

Alison M. Gingeras: Last time I was in your studio, right before you sent the paintings to Los Angeles, I was simultaneously impressed by the new elements in your work and the consistent through-line of selfportraiture that you continue to practice. With each canvas, you’re pushing the genre further, which I think will be quite evident in the grouping of eight you will show in LA. One thing that I noticed was your collection of porn magazines you had spread all over the floor. These aren’t just any old porn magazines—they are super specific to Poland’s history and to the radical social changes that took place during the transition from Communism to Capitalism in the early 1990s. Why did you start collecting those? How have those images transpired upon your new works? Why are they compelling for you? So many of your new dynamic narrative compositions are perhaps coming from those magazines?

Agata Słowak: These are not randomly selected magazines! These Polish erotic magazines from the 1990s interest me on several levels. What fascinates me is a certain kind of nostalgia (I was a child during this transition period, so obviously, I wasn’t aware of its gravity). These magazines are aesthetically and distinctively pre-internet, so they’re noteworthy. More significantly, they were being published at a moment when people began talking about sexuality in Poland. In the times of the Communist Polish People’s Republic, Poles’ sexuality was suppressed and superficial, an important social trend that was reinforced by the dominance of the Polish Catholic Church.

These porno mags are also incredibly interesting visually, due to their naturalism and the limitations of resources at the end of the last century; there is no retouching, no plastic surgery, and virtually no access to professional make-up artists. The photo editorials depict “real” people, paradoxically, somewhat escaping the patriarchal canon of beauty. They’re a wonderful time capsule, bearing imperfections at different ages, social structures, and sexual orientations.

And apart from this type of inspiration, these magazines make great reference material for models! We find expressive readymade body arrangements that are fantastic for dressing up in compositions and painting—these photos are not easy to find on the internet today. The images are very niche and have a strong character of time and place, making them unique.

Another striking departure in this work is the appearance of more direct symbolism. Can you talk a bit about the Polish Eagle that appears in one of your self-portrait nudes, Polka / Jaki kraj taka Prometeusza // Pole / Such a Country Such a Prometheusess (2024)? There have always been some sly elements of Polish identity in your works—very codified landscapes, Catholic references, rural settings—but the Polish Eagle is such a monumental and official signifier. I’m wondering what prompted you to insert such a loaded symbol into one of your recent tableaus.

The work with the eagle was created during the holidays, when I was visiting the region where I grew up. I came across the small village of Zalipie, where I discovered wooden houses painted by a women’s guild. One of them had an eagle made of pinecones—it was all based on a strong sense of Polish identity; I felt something native about it, something unique. I also don’t like it when symbols related to patriotism are appropriated by the conservative side, nationalists, and right-wingers. I believe that representatives of minorities also have a civil right to these symbols.

There are so many indelible images that stuck with me during our studio visit. The lady humping a cactus, pictured in Down in Mexico (2024), was one of the most memorable images that haunted me. Can you tell me about this picture? Who is she? I feel this is an allegory, but I would love to hear your narration around this stunning work.

In a way, it’s about the strength of this woman; I wanted to visualize the increasing desire for a certain insatiability and think about the limits of the strongest orgasm. Is there a limit? This cactus can express something seemingly strong, giving strength and security, such as a man with a strong position, a prize in a competition, and such. This painting is actually not quite my style— the Mexican atmosphere is a real departure, but I just wanted to paint this strong motif.

The appearance of “non-finito” is a new element in your forthcoming show. I very much liked these deliberately unfinished, rather gestural paintings. And I particularly liked seeing them hanging side by side with your more “classical” signature style of this renaissance technique, deploying layers of underpainting that you usually utilize. The tension is super interesting, and to me, the images feel a bit like the remnants of dreams...how one remembers strong dream-images without recalling the storyline or only fragments that float in the haze of your memory when you wake up. Is that something you were thinking about at all?

I’ve long been drawn to the unfinished, as a conscious decision. Both in the contrast of the detail, such as a portrait and the background, as well as in a certain type of gestural painting technique. I don’t want to give up on overworked narratives that have many layers and are built slowly on the canvas—but expressive, intentionally unfinished works allow the concept to remain fleeting and have a dreamlike expression. The concept of combining this gesture with sleep is beautiful and seems extremely accurate to me. What remains from intense sleep is essence and fragmentation.

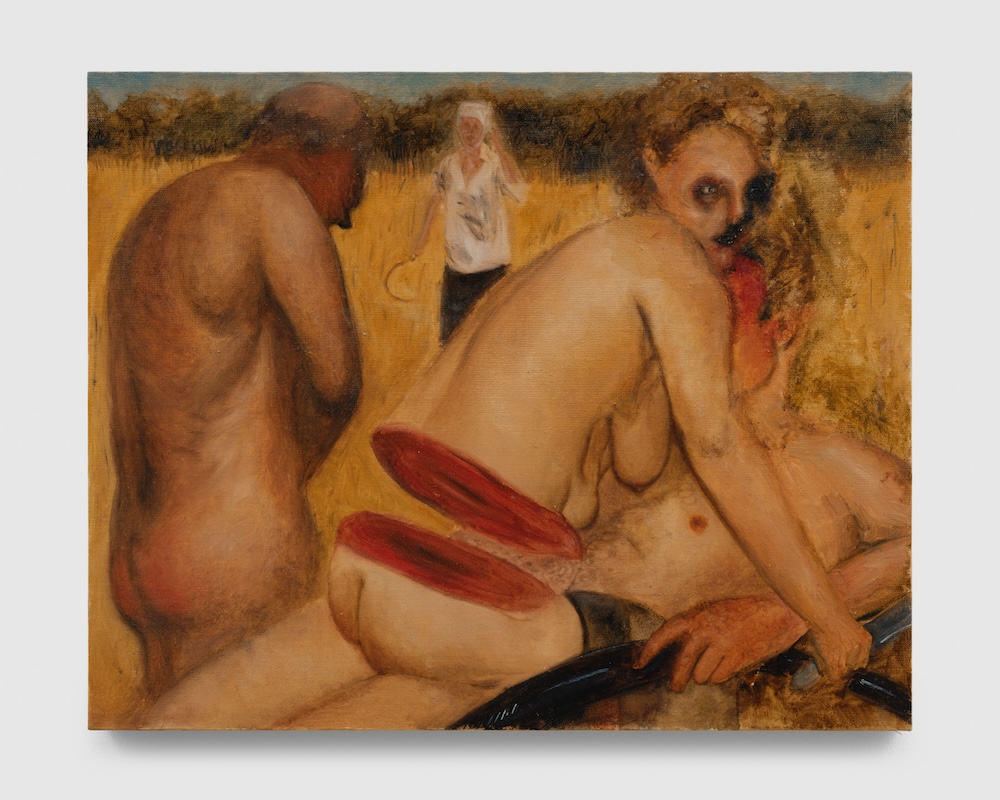

Dream space is a major trope in your work, not only in these hazy, fractured images but also in the sense that certain themes and symbols reoccur frequently. One such theme that is in this new body of work, and also very present in previous works, is the question of reproduction. The possibility of procreation, your internal struggle with potential motherhood, the desire and repulsion of childbirth, the visceral depiction of the body as a potential vehicle for reproduction: the question of having a child seems to haunt you. And like with dreams, the recurrence of childbirth imagery is both consistent and shifting in your work, from painting to painting. It is as if reproductive justice and the maternal compulsion seem to be in conflict in your work— just as they are in our socio-political sphere?

You’re right that painting can emerge from that part of consciousness as dream fantasies. There are people and motifs that come back to us from the subconscious, relationships and themes that seem to organize our lives, hanging over us like ghosts. The topic of reproduction is extremely vivid and topical for me, and I’m not just talking about the current political fight for abortion rights, just personal dilemmas arising from the opportunity my own body potentially gives me. How many life-shaping decisions resulted from the very fact that such a choice is a viable option? We feel the pressure of a ticking clock. Since it doesn’t happen passively, how should one make a decision? When? With whom? And how, so as not to miss out on commitments and work? On the one hand, one can be a mother of art and treat it as one’s relationship and offspring, accepting that perhaps there are other things one is called to do, opposed to most people. On the other, there’s the feeling that one is giving up such an intense experience in life. Freedom and independence have their weak points here. Painting only perpetuates this lack of answers. On the one hand, the atmosphere of the family home is a simple expectation of a physical extension of life. On the other, there’s the devastating fear that accompanies a late period—that despite being sexually driven, the person isn’t ready for parenthood, and that the creative state would be ruined.

This interview was provided by BLUM Gallery in conjunction with Agata Słowak's SZTUKĄ DIABŁA TŁUKĄ