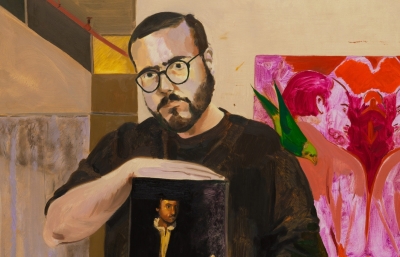

PM/AM is pleased to present The Dreams I Don’t Remember, a solo exhibition of new works by Daria Dmytrenko. The artist conjures creatures that dwell somewhere between nightmare and self-portrait. Her figures—amorphous yet anatomical, grotesque yet majestic—emerge from the recesses of her subconscious, relics of a prehistoric psyche. Alongside the paintings, the exhibition also features new sculptural extensions of her mythology.

Dmytrenko’s creative practice is akin to meditation; keeping her mind entirely blank, she allows unconscious imagery to surface. The creatures come unbidden, warped by the Slavic mythology that pervaded her childhood fears. While these beings have always haunted Dmytrenko’s practice, in earlier works they were far more abstract. Now they arrive with flesh, muscle, wrinkles—even teeth. They grow increasingly specific, as if sharpening in resolution. Dmytrenko’s work often elicits the same reaction; recognition, an emotion shared by the artist. It is only then she knows a piece is finished.

Dmytrenko's aim is not to distort, but to reveal—not to escape reality, but to explore its foundations. The works speak to a collective unconscious, carried by the same mythic current that connects Grendel’s mother with Plato’s fractured creatures; beings with a forgotten majesty, both foreign and familiar. Although her creations evoke Bosch’s hellscapes, their visceral rendering is different in design. Where Bosch revels in all that is crude and sordid, Dmytrenko wields anatomy to exalt, rather than to debase. She finds grandeur in the grotesque, leaving the search for beauty forgotten and unimportant.

Dmytrenko’s subjects are inherently feminine, recalling that they are first and foremost self-portraits, each a mirror held up to the innermost recesses of her mind. It is for this reason they are painted in caves and forests; places of secrecy and concealment where the subconscious is at home. Dmytrenko's fascination lies with that which is typically maligned — the sagging and folding of skin, refigured here as a locus of meaning rather than defect. Dmytrenko privileges age and monstrosity in the place of youth and beauty, emancipating her creatures from any superficial connotations of femininity and leaving only divinity and immortality. The visual politics of our world throw those in Dmytrenko’s into sharper relief. In her primordial vision, there is no ‘aesthetic’ eternal life, no wisdom untouched by malevolence. —Chloé Beroud