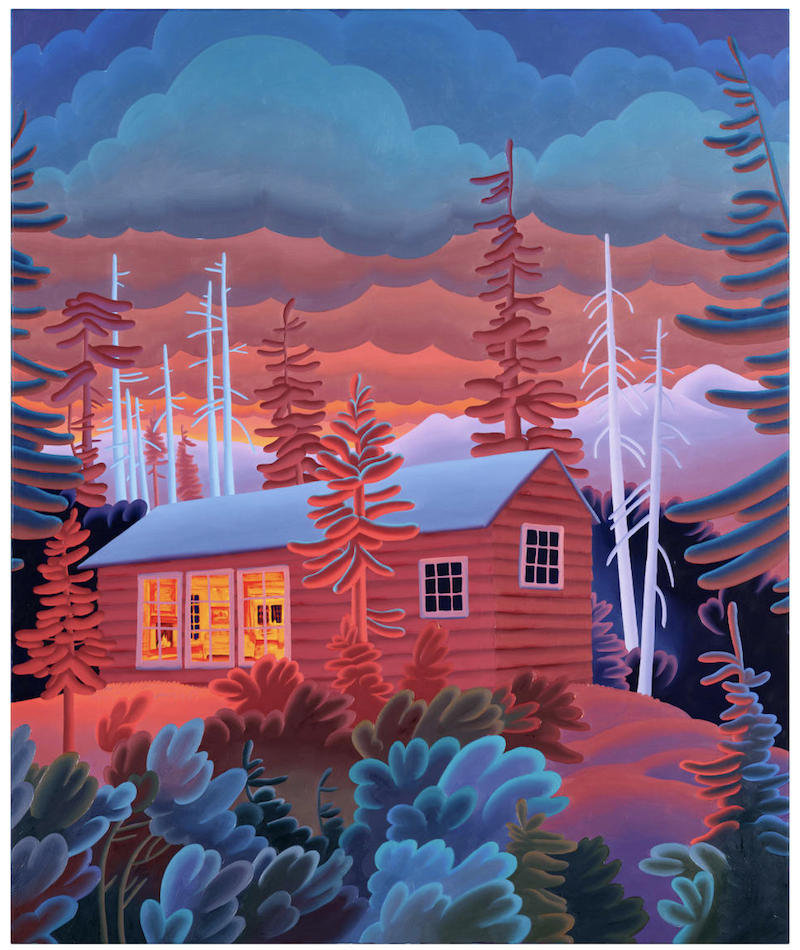

Walking into Madeleine Bialke’s second solo exhibition at Newchild feels like stepping into a haunted forest of memory—an unearthly terrain where the living and the spectral converge. Eidolons, a term borrowed from Walt Whitman meaning “spiritual images of the immaterial,” captures the essence of this new body of work, painted over the course of this year, and born from a brief but profound journey through California’s Sequoia National Park.

Earlier this year, just days before wildfires swept through the Los Angeles metropolitan area and San Diego, Bialke spent two days walking among some of the oldest living organisms on Earth, 300 kilometers north of Los Angeles. The immensity of the redwoods—giants that have witnessed millennia—left an indelible impression on the artist. “The trees themselves are ghosts in my mind,” she reflects, “they hold a presence, a purpose, but they are now immaterial—images in a visual diary.”

This exhibition is both an homage and a reckoning. Through Bialke’s fractured memory, the Sequoias rise as monumental figures of time—towering, near-mythic beings whose forms bear the marks of humanity’s impact on the climate, yet endure with quiet resilience. Their rings carry the memory of fires, storms, and centuries of change, as if the story of the Earth itself has been etched into their living flesh. Bialke holds these images like relics or “eidolons,” preserving what is most precious before it slips into history. Yet the forest she recalls is not untouched: it is encircled by wide, barren mountains where, as she describes, “swaths of trees have been burned to skeletons by increasingly violent wildfires.” These ashen slopes—silent graveyards that fringe the living grove—become the shadow to the Sequoias’ endurance, a reminder that their survival is neither inevitable nor guaranteed. In the interplay between the lush sanctuary and its scorched periphery, Bialke captures the dual truth of our era: that beauty and ruin, life and loss, now stand side by side, each made sharper by the other.

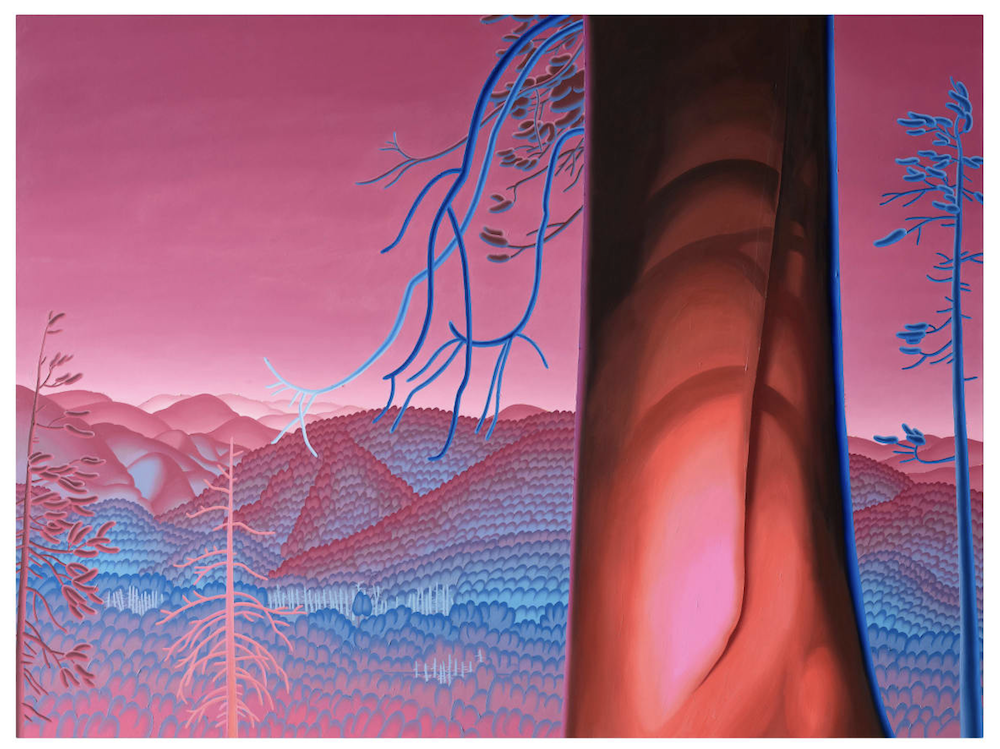

In her painting Ghost Town, the viewer’s very presence becomes part of the work. The bark of a colossal tree glows with a warmth that seems to emanate from the observer, while purple, wave-like mountains recede into cool shadow. Here, Bialke explores the idea that consciousness is not simply a product of physics but a foundational element of reality itself. “Plants are more likely to have some kind of consciousness than not,” she notes. “They strive, care, witness.” Standing before the canvas, we are not passive onlookers but active participants—sources of light whose presence alters the scene. The painting becomes a quiet call to action, suggesting that if we can leave an imprint on destruction, we can also become catalysts for renewal.

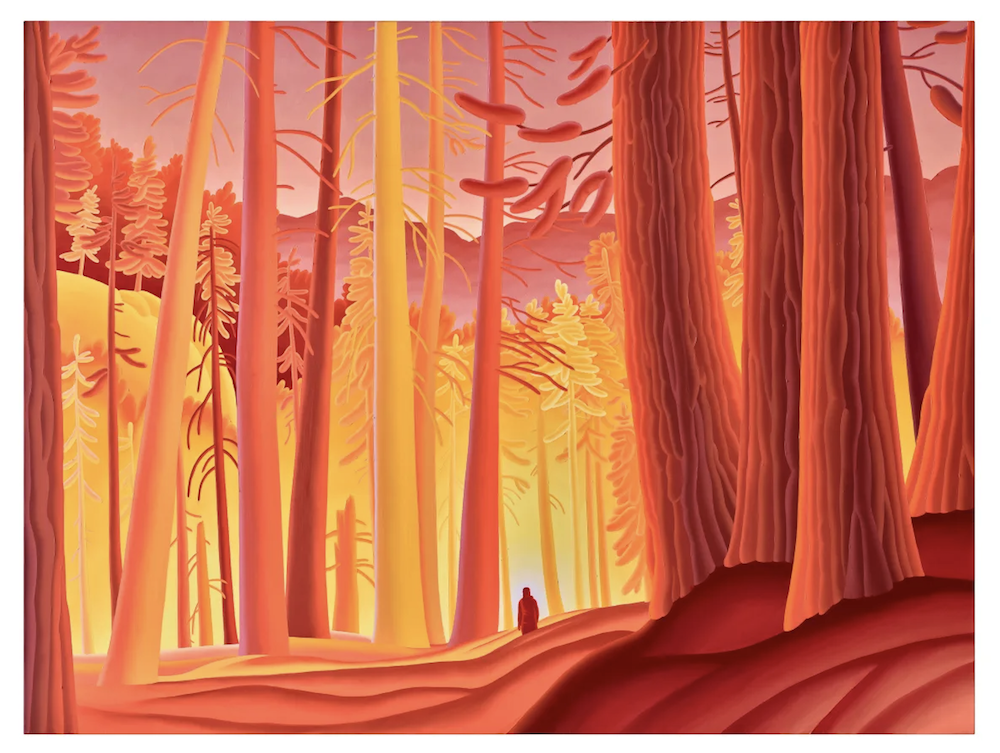

This heightened, almost pantheistic spirituality runs throughout the exhibition. Like Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Bialke’s paintings suggest a democratic, embodied communion with nature—an understanding that humanity is not separate from its environment but entangled within it. In Life On Earth, a sweeping landscape unfolds where a lone figure wanders through a luminous, almost otherworldly forest. The scene recalls the Romantic sublime of Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea, yet here the wilderness feels both cosmic and unfamiliar. The figure, rendered minuscule against towering, alien trees, moves like a pilgrim across what could be another planet—only to realize it is our own, reshaped by ecological upheaval and time’s relentless passage.

Time, too, is a material in Bialke’s work. Each painting is built slowly, altered and reimagined as memory shifts. Earlier layers remain visible in “blips” of paint—ghostly residues that gesture toward what once was. In Out Yonder, a figure stands inside a monumental tree that divides the canvas into dual worlds: past and future, preservation and destruction, hope and its shadow. These contrasts echo Naomi Klein’s notion of a “mirror world,” where for every preserved vista, another forest burns unseen.

Despite its quiet reverence, Eidolons is not a passive contemplation. Bialke sees the viewer as an active participant, a source of warmth and light shaping the scene itself. “Even walking in and among the sequoias,” she recalls, “our very footprints changed the landscape. We scurry like gnats around these giants, moving too fast to understand the consequences.”

And yet, there is a tenderness—a possibility of relearning harmony with the natural world. Avery F. Gordon writes that to follow ghosts is “to put life back in where only a vague memory or bare trace was visible… toward a counter-memory, for the future.” In Bialke’s forest, these counter-memories flicker like afterimages, refusing to let the world’s living essence be forgotten.

Like Norwegian painter Peder Balke, who painted the North Cape for the rest of his life after a single summer there, Bialke’s brief encounter with the sequoias has become inexhaustible. Through these paintings, she offers us a walk into that forest—a chance to stand among giants, to feel time’s weight and its fragility, and perhaps, to glimpse the unseen essence behind all things.