PLATO is thrilled to announce Stass Shpanin's solo exhibition, Forbidden Garden, on view through October 4. The Philadelphia-based artist Stass Shpanin focuses on interpretations and fabrications of the past that reverberate in the present. His hand-painted canvases combine centuries-old American folk imagery with AI technology to deconstruct the vocabulary of myth-making and examine the visual mechanisms aff ecting public memory.

Stass Shpanin was born in Azerbaijan, formerly the Soviet Union, and has lived in the US since he was a teenager, so he is no stranger to countries and ideologies coming and going, and the imagery associated with them transforming along the way. Images of birds, animals and plants have appeared in the insignia, fl ags and offi cial documents of many states and municipalities for millennia, their meanings often similar yet adjusted to a particular context. When Shpanin discovered pictorial examples of these archetypal symbols in German “fraktur” — illuminated works on paper produced by German immigrants to Pennsylvania from mid-18th to mid-19th centuries — he had an aha moment.

The creators of fraktur were commissioned by their communities to illustrate birth and baptism certifi cates and other offi cial records. They freely combined text and image, and often exercised liberty with colors and scale in their compositions exuding humor and joie de vivre. Perhaps the work of these artists, who were so imaginative and irreverent while constructing their clients’ histories via pictorial means, can stand in for a parody of the imagery of state offi cialdom, a similarly arbitrary selection of symbols produced with less innocuous purposes. If so, perhaps by reconfi guring and abstracting the former, one could reveal the mechanisms behind and the objectives for masterminding the letter.

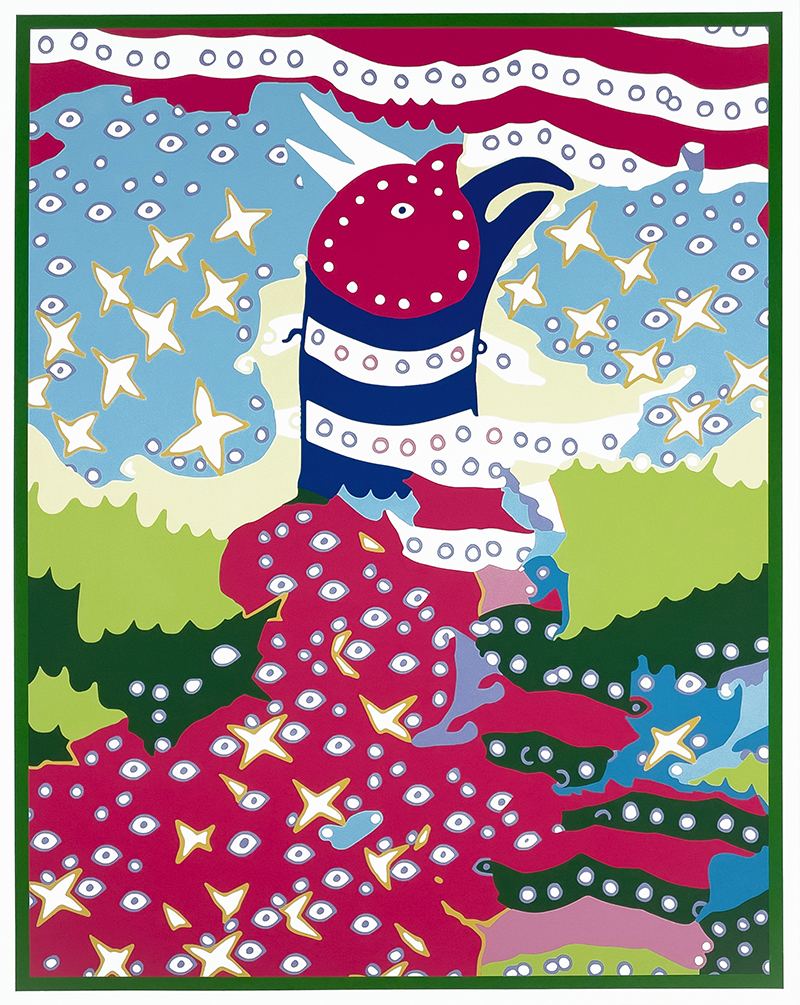

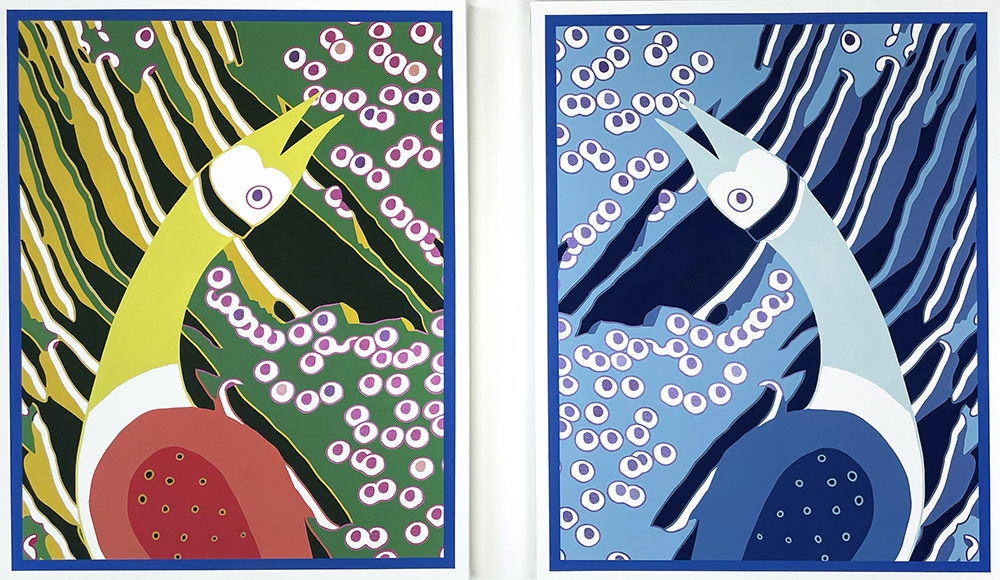

To create his paintings, Shpanin chooses an example of fraktur, digitally breaks it down into parts, then repeats these fragments and combines them into new compositions, often allowing the glitches in the system to be his collaborators. These digital collages are then transferred onto canvas with the help of stencils made on a vinyl-cutting machine. The stencils guide Shpanin’s meticulous, slow, multistep application of Flashe paint. The artist’s digital alterations take solid and permanent form via vibrant, vinyl paint applied by hand, similarly to how glitches in memory and history forge false or twisted narratives — at times intentionally, at others circumstantially — that are often believed to be true.

One such made-up story is encapsulated in the painting titled Ms. George Washington Jr. (2024). Shpanin’s work, attuned to both the history of the US and the history of art, is a darling of many museums. When he had an exhibition at the Phillips Museum of Art in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the artist painted a likeness of George Washington that was to be paired with a portrait of Ann Lawler Ross by Benjamin West in the museum’s collection. Shpanin imagined a scenario in which Washington, who was childless, married Ann Lawler Ross, instead of his actual wife Martha, and had a daughter with her. A product of that myth is the full-length portrait of Washington’s daughter, Ms. George Washington Jr., interspersed with a few red apples — a reference to the popular but entirely fabricated narrative about Washington’s childhood.

According to the story, devised to highlight his honesty, a six-year-old George Washington cut down his father's cherry tree with a hatchet and then confessed his actions by famously saying, “I can't tell a lie, Pa; you know I can't tell a lie.” Thus, a fi ctional account meant to be an early lesson in honesty for young Americans is mixed with a character made up by the artist, possibly to encourage the viewers to refrain from blindly believing historical records.

In an overtly tongue-in-cheek manner, Shpanin titled another painting in the show — featuring a borrowed fraktur character with a raised hand — Hi5. The artist multiplied the man’s facial features across the top of the painting and placed him in what looks like a lake with a glitchy, abstracted shape, “as if he is ice-skating,” and superimposed a fi gure of an oversized rabbit onto him. A strong colorist, Shpanin fi lls the painting with modern hues, turning historical folk art upside down and infusing it with contemporary fl avor and timeless humor.

The only sculpture in the exhibition, intriguingly called Love Story, is a duo of white tombstones with reliefs of a woman and a matching parrot of human proportions — a Carolina parakeet, native to and once ubiquitous in New England until they were driven to extinction in the early 20th century. They form yet another set of characters flipping the tradition of venerating historical figures on its head.

Other protagonists in this Garden of Eden seen through the lens of American folk art are the inescapable eagle, covered in white stars multiplied by AI; a shy burgundy lion, a whimsical parody of the universal symbol of pride and bravery; a snake wrapped around the tree trunk, alluding to the 1754 “Join, or Die” cartoon published by Benjamin Franklin as a call for the colonies to unite during the French and Indian War — and also a possible reference to the original sin; male mermaid clasping hands in campy reverie; and a bird-like angel in flowery garlands. Forbidden Garden is colorful and full of charismatic characters. It is in a constant state of flux shaped by the artist, by history and by its visitors, who are expected to have agency and critical abilities to ultimately decide its meaning and purpose.

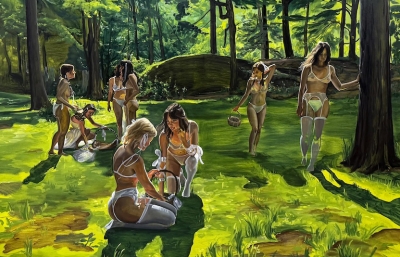

In Forbidden Garden, Shpanin fuses Biblical and historical references and archetypal imagery alongside portraits of real and imaginary figures in faux-naive graphic style in order to peek beneath the blissful surface of both American and universal idylls, and to probe the accidental and intentional mechanisms behind their creation.