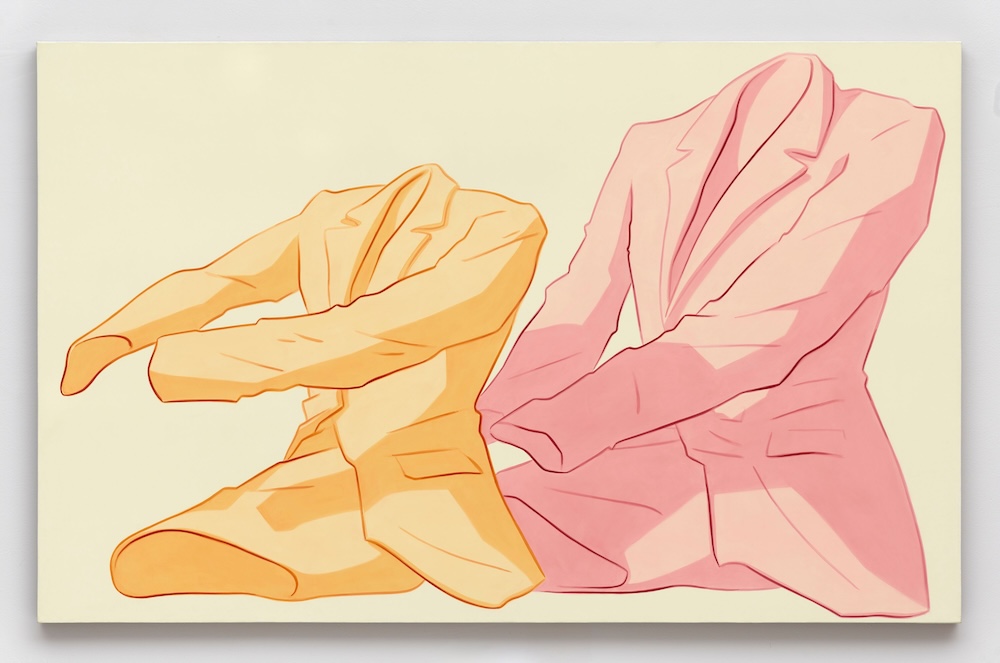

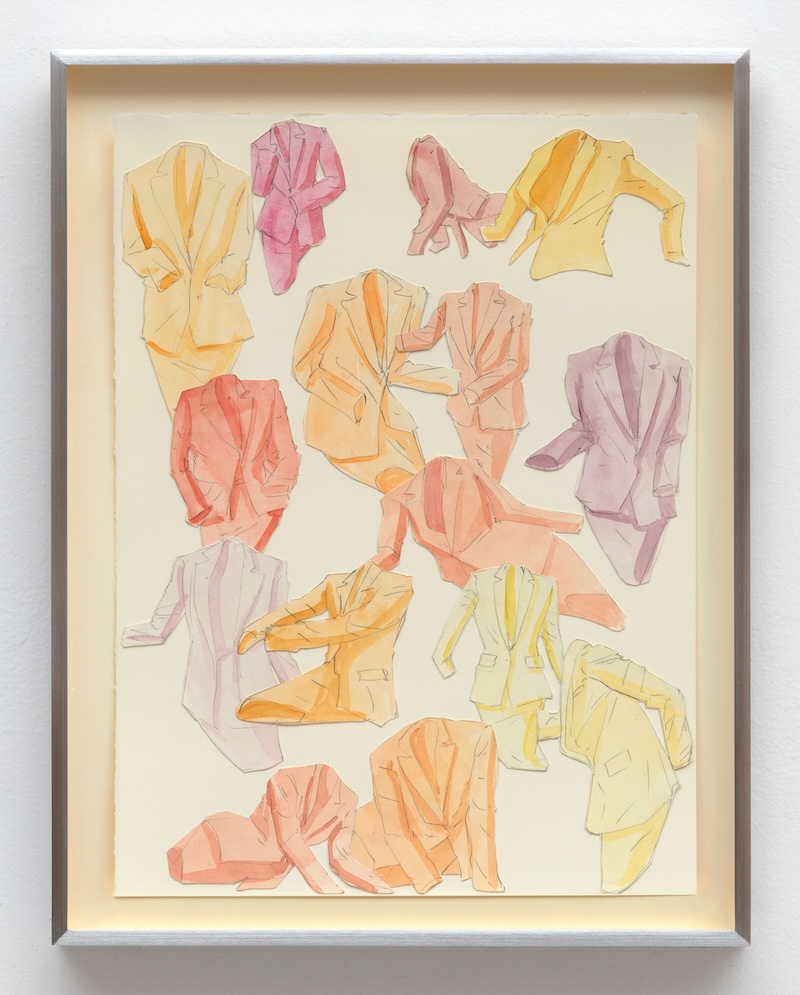

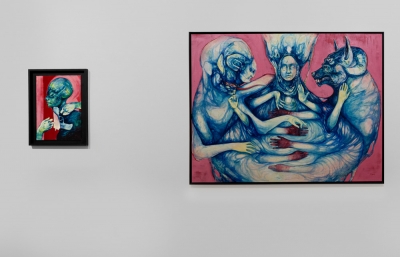

Ivy Haldeman is known for hot dog people, bananas and empty suits. When I asked her earlier this year about just the emotion of the hot dog works, she told me "I think this leaves room for the viewer to incorporate themselves in the scene, as you’re suggesting, both physically and empathetically. It's meant to be inviting, to start a conversation." She left some of the hot dog works behind in her incredibly poignant in The Agreement, The Fool, and The Storm at Ghebaly earlier in 2024, massive paintings of floating, flowing bikinis and empty suits sort giving both anominous and fleeting feel of freedom and the means to get to there. When we spoke with her, that is what she was working with: the idea of which we get to freedom, the acts of perversion of the story once we are there, and how we live with the self knowing how much of what we enjoy comes from things we cannot escape.

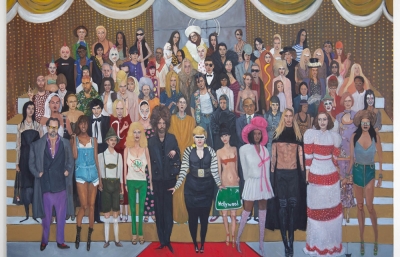

Nanuzka Underground in Tokyo is set to open On Human Form, Ivy's new solo show which feels like a more in-depth look at America's fast culture and Ivy's work in Pop Art's history.

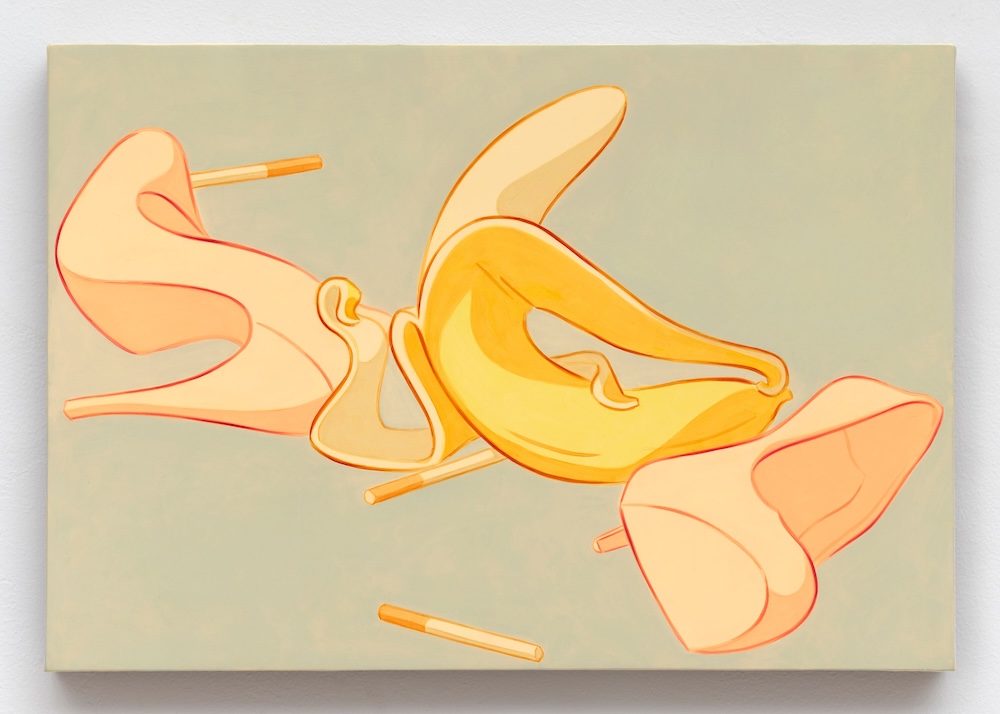

The gallery notes, "The objects in Haldeman’s work also function as devices to deconstruct selected subject matter in classical still life painting and portraits from a feminist perspective. For example, fruits, especially grapes and peaches, have conventionally been depicted as symbols of “wealth” and “dignity” in still lives, yet as the term “still life” implies, these objects do not evoke their own emotions or their relationship to human beings and their movements, including domestic labor which has primarily been undertaken by women. Bananas on the other hand, which Haldeman also depicts, are a relatively inexpensive and vulnerable fruit that has come to be distributed in the United States as a result of global capitalism. Their handling as well as the act of peeling them to eat harbor deep connections to the human hand. By reducing the size of her works, Haldeman strategically emphasizes the contrast between her paintings and traditional still lifes."

At this current moment in the American experiment, to be away from the country in a place with so much imperial history adds a contextual element to what Ivy creates. And perhaps perfectly put, when we spoke with Ivy this summer, she noted that Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru was the last best piece of art she had scene. Ivy said, "There is a scene where a woman speaks so passionately about constructing wind-up rabbits! It’s her reason for living. She says, 'When I help to make these in the factory, I feel as if I am playing with every baby in Japan.' It’s spectacular." —Evan Pricco