The interrelation of desire—deferred or briefly fulfilled—and entertainment is the current that runs through Jane Dickson’s five decades of work. The artist made her earliest paintings of carnivals and theme parks in the 1980s, while living in Times Square—another place promising pleasure for the right price. She translated imagery from her photographs into nocturnal compositions in which the neon lights of ferris wheels and game booths pop against inky grounds. Still fascinated by the way spectacle can take us on a ride, Dickson revisited the subject matter in the first years of the twenty-first century. Featuring paintings made between 2004 and 2025, Wonder Wheel emphasizes how fairgrounds seduce not despite their artificiality but because of it.

Dickson represents New York carnivals such as the Feast of San Gennaro and Coney Island’s amusement park from a multitude of perspectives, simulating the way visitors’ gazes shift and intersect as they rove around these urban fairgrounds. San Gennaro is intimately tied to Dickson’s earliest years in the city: her first studio in New York was located on Mulberry Street, at the epicenter of the crowded festival. San Gennaro Up in the Air 3, Study and San Gennaro Up In the Air 2, Study I (both 2007) present views of ferris wheels as seen by the rider, situating the viewer in midair. Dickson’s emphasis on the symmetry of the iron spokes evokes Joseph Stella’s late-1930s paintings of the Brooklyn Bridge. From the Ferris Wheel (2025) shows the stark shadows cast by beaming lights as seen from a gondola just as it begins to ascend; the work is the result of Dickson’s practice of combing through her photographic archives to find images that have since gained new potency. Baroque Chair-o-plane (2005–21) pulls back, showing riders being flung outward by the machine’s centrifugal force. The artist has omitted the cords suspending them, and, untethered, the figures could be flying or in free fall. From this body of work but not on display here, Big Oval (1985), in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, steps back even farther to portray not the human experience of amusement parks but their electrified architecture’s dominance over the horizon. An interrogation of voyeurism—of, in her words, the desire “to see, to know, without being seen or known”—runs through Dickson’s work, from peep shows to sideshows.

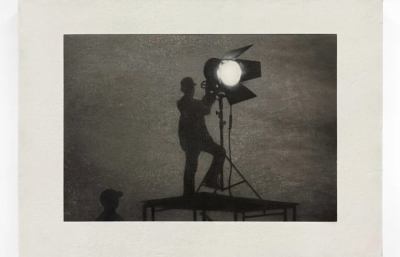

Rather than beginning with a traditional white canvas, Dickson often starts with materials whose idiosyncratic textures carry their own associations. The vinyl that acts as a substrate for the majority of the works in Wonder Wheel has its origin, like their subject matter, in the 1980s, when she stumbled upon a roll of textured gray vinyl at Materials for the Arts, a nonprofit that salvages supplies for reuse.. The waxy body of oil sticks—pigments and oil compressed into crayon-like, handheld implements—jumps over the nubby vinyl as it is applied, allowing specks of dark to peek through otherwise opaque passages. As Linda Yablonsky wrote in 2005, oil stick “dries hard and slow, pixelating [Dickson’s] canvas and giving her images the grain of surveillance photos, taken in secret.” Unlike tubed oil paint, which can easily be mixed to create an array of tones, the set colors of oil sticks can only be modulated through layering. The readymade hues echo and reinforce the sameness of a mass of identical prizes hanging in a booth, circus tent stripes, and latex balloons. In Rhode Island Striped Tent (2005–25), the blue and yellow bands of a big top swag down from a central beam decorated with bright spotlights, their halos represented by flecks that disperse into the surrounds. In the artist’s funhouses, relief from the everyday is as transcendent as it is fleeting, and someone is always watching.

https://karmakarma.org/