Perhaps the multitudes we are cannot fit within the person we show. Surely, all that crowd suddenly peaks through cracks, lurks when we are silent, slips in at some point in the day, or takes us by surprise with its appearances. We may have to disguise, mask, or mimic ourselves to explore those other unknown bodies.

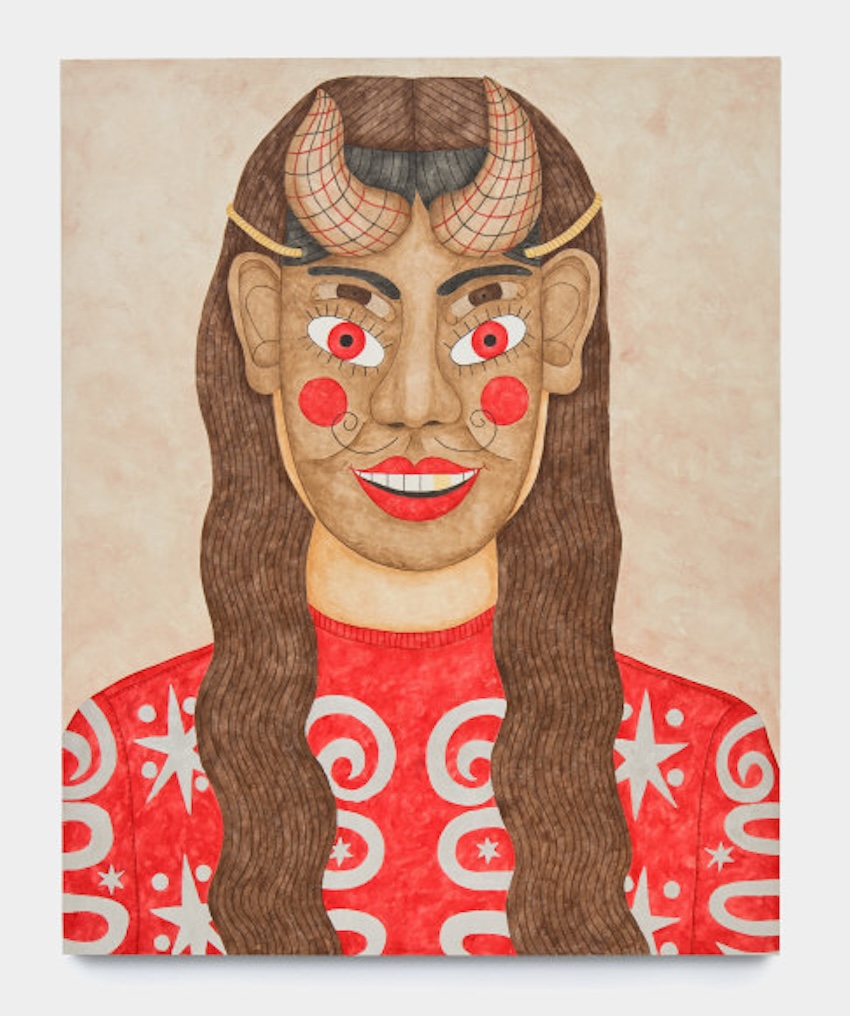

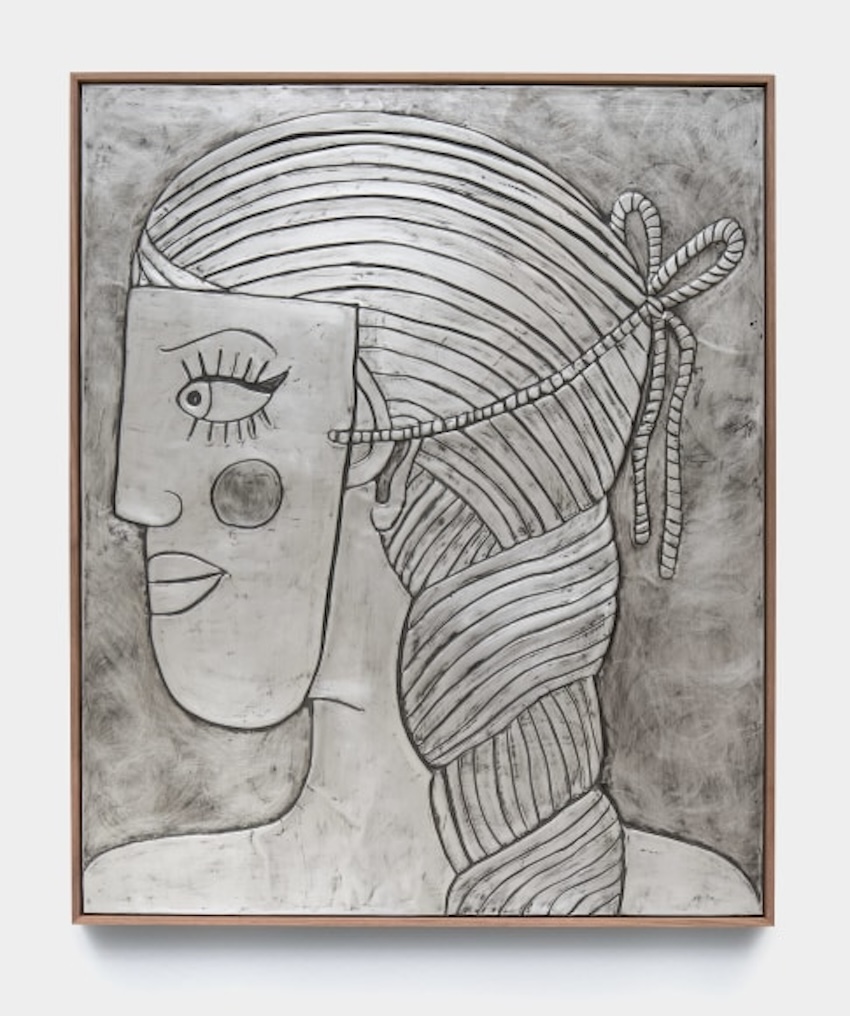

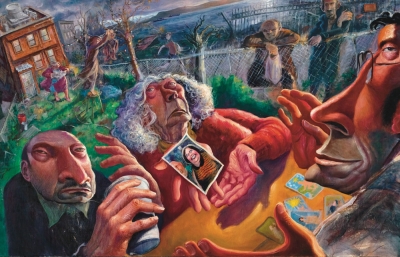

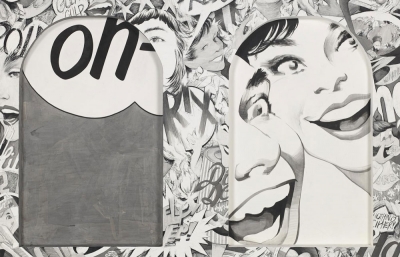

Liz Hernández, who has previously worked around the multiplication of the self and the fantasy of personality, explores in this exhibition the power of the mask and its enticing and repulsive mystery, the one that allows us to evade our constraining identity, to be several at once or to become no one.

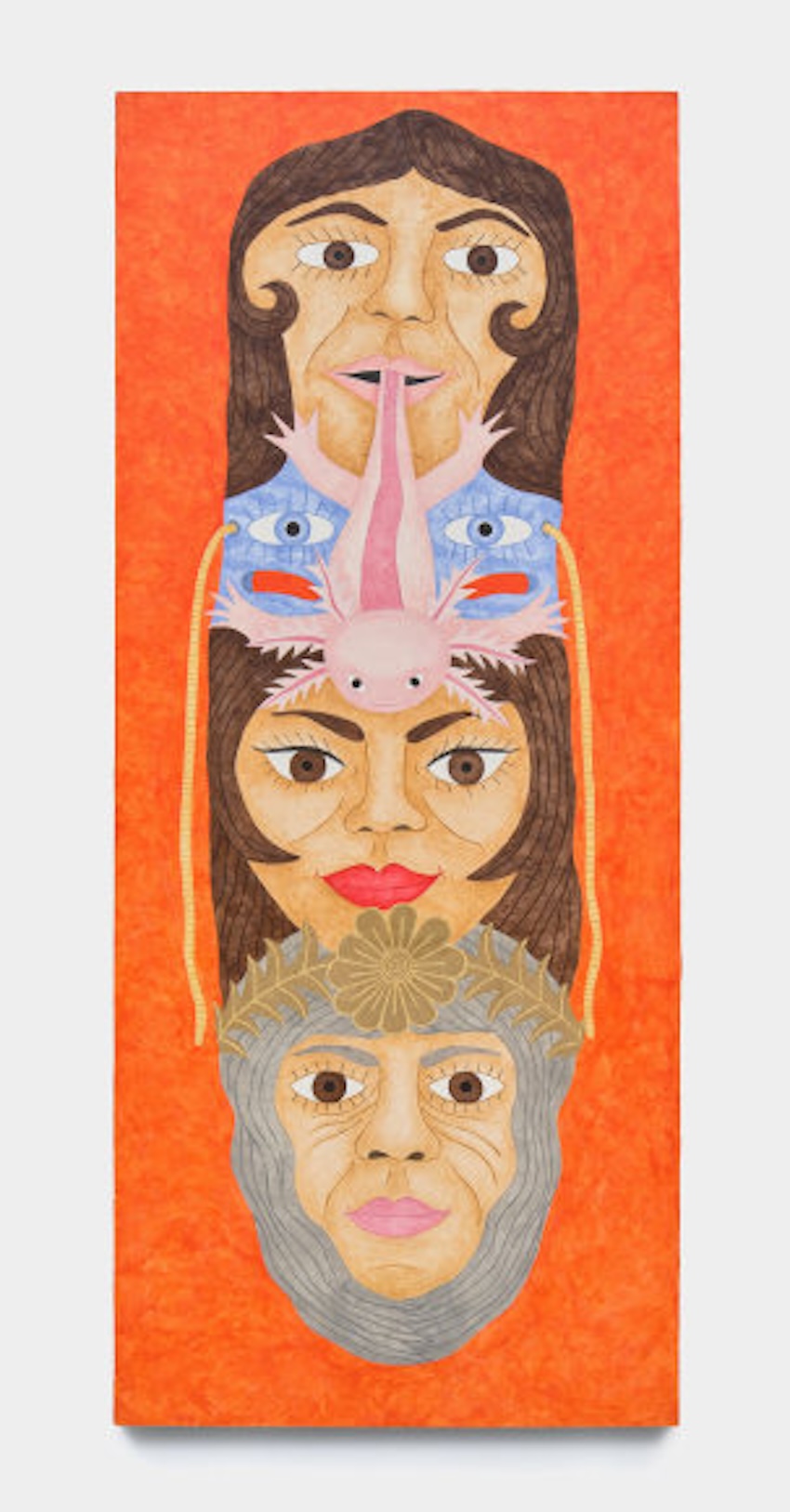

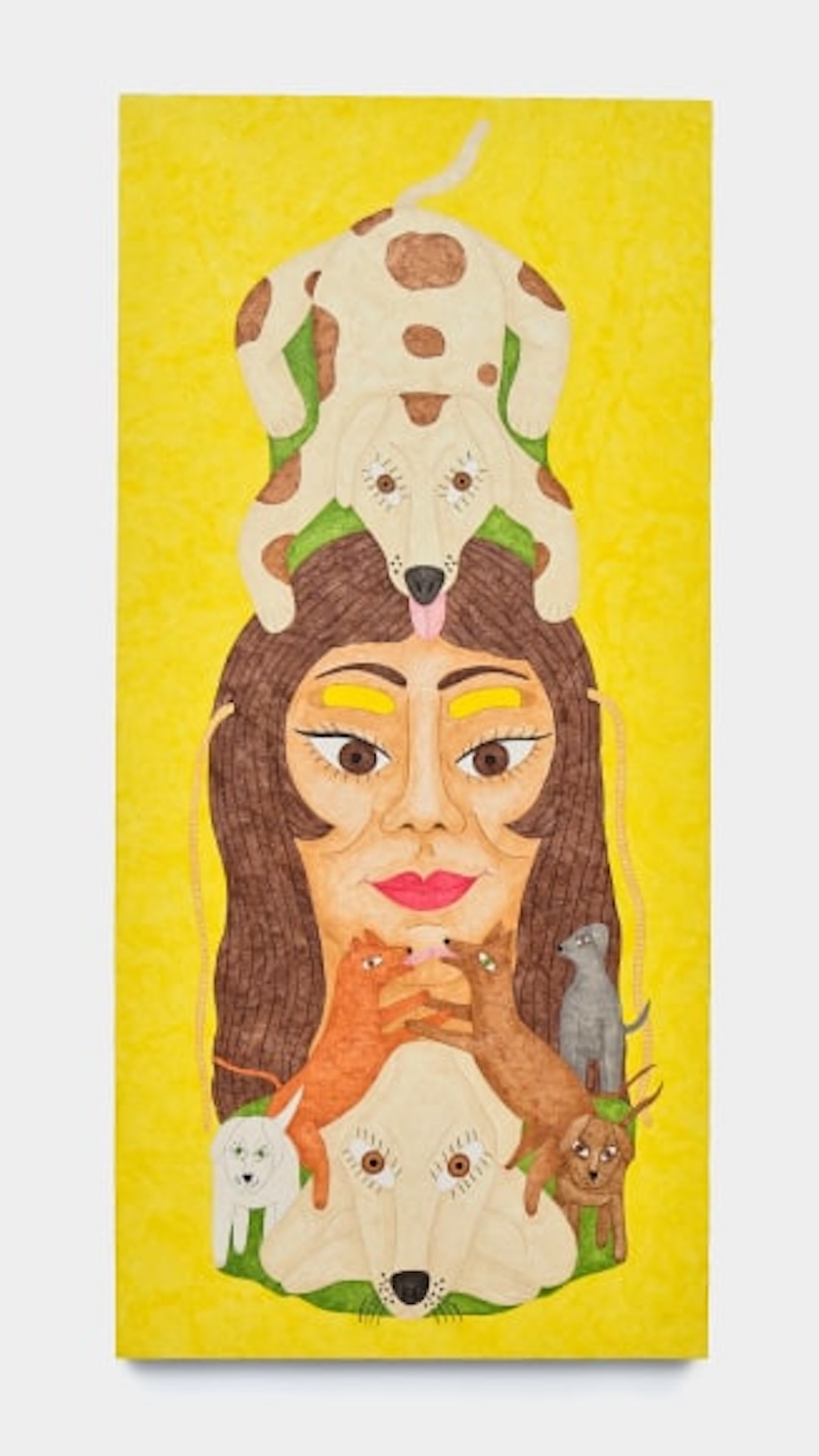

In the masks that populate these rooms, two, three, or four pairs of eyes can coexist: those of a serpent, those of a woman-man, those of a dead person, those of water, an axolotl, or a dog. And it seems as if with all those eyes it were possible to see, at the same time, the world of the dead, that of animals, humans, or of rivers; that is, as if those piled faces full of eyes allowed not to have a single or firm gaze, but a diverse and scattered one.

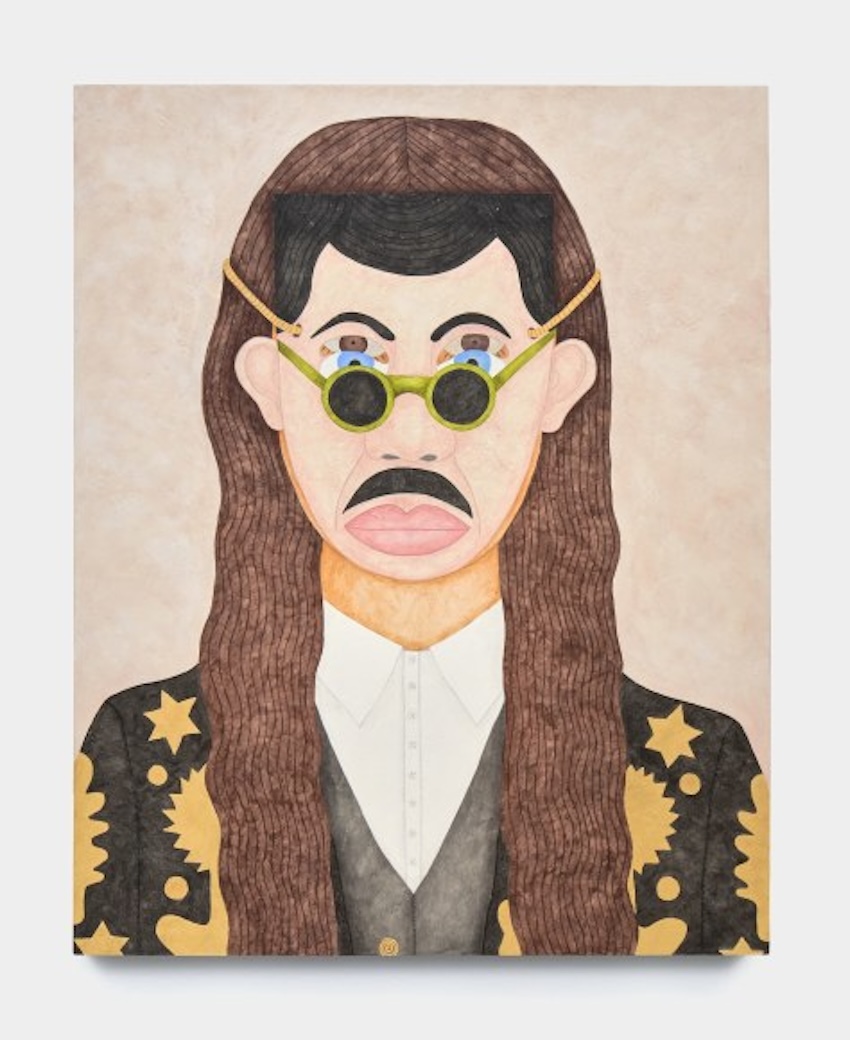

The mask as an artifact enables so many movements and pleasures that it may be fair to strip it of its negative or deceptive burdens. Since it makes us, for example, lose fear, invert class or gender roles, suspend judgment, and be everything we would like to be if there were no consequences. It allows us to rebel against the so-called "true version" of ourselves to unfold other narratives in which we can even alter time: to be a girl, a woman, and an elder at once.

In the dances and rituals of the various groups that coexist in Mexico, the mask is a very present element. It is a tool of metamorphosis that has allowed communication between the earthly and the supernatural realms for many centuries. In Liz Hernández's imaginary, always nourished by folk art and ritual, complex characters reside, such as the devil, who, unlike the dark and malicious charge usually attributed to him by Christianity, is for other worldviews a mischievous and joyful figure who mocks without malice because he has permission to play.

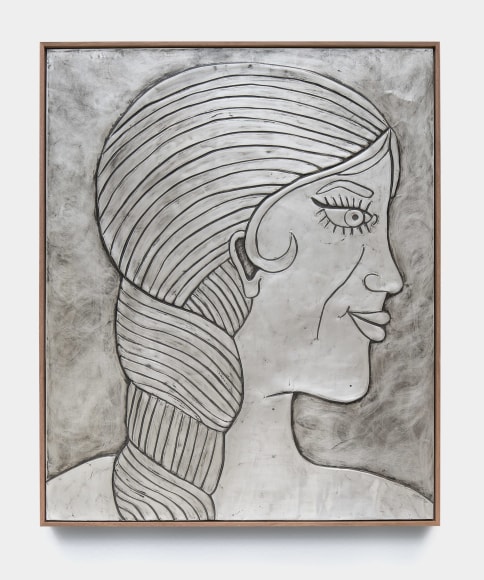

Just as in the scene painted by Liz Hernández where a woman appears carving her own masks, in some towns in Mexico, there is a very intimate relationship between the person and their mask, as it manifests the strength of the one who wears it. That is why each dancer must carve their own and imbue something of their being into it. When the person can no longer use it - because they have lost their strength -the mask is kept until the death of its wearer and then placed in their tomb until the person and mask disintegrate. Perhaps they have always been the same, or have always been integrated, because who really lives behind the mask? —Valeria Mata

https://jackhanley.com/