P·P·O·W is pleased to present Running Water, Elizabeth Glaessner’s fourth solo exhibition with the gallery. In this exhibition, water becomes an inescapable force dissolving the boundaries between body, landscape, memory, and the present in an incessant flood. Glaessner utilizes poured pigments mixed with various mediums and layers of rich oil paint, mimicking the fluidity of water, to create permeable narratives in which figures continuously ebb between formal articulation and non-representational gesture. Throughout this new series of large-scale paintings and works on paper, Glaessner submerges moments of miraculous transformation in dreamlike landscapes where the lines between birth, death, creation, and excretion are porous and ever-changing.

Combining art historical, mythological, and cultural references with childhood memories and the subconscious, Running Water resists familiarity and nostalgia, instead submitting to the new and unknown. The swampy landscape of East Texas, particularly its rivers and streams, haunt Glaessner’s symbolic compositions. As a child, Glaessner recalls playing in the bayous and floodwaters that now threaten whole communities and their natural surroundings. Throughout the exhibition, bodies and bodies of water are presented in a perpetual exchange, highlighting humanity’s inextricable link to these hydrological systems. As our environment becomes more compromised, so do our bodies and the notion that we are sealed, impenetrable, and autonomous beings.

In Dissociating on a rock, 2025, a prone figure lays atop a boulder on a murky beach. A ghostly apparition springs up from her rounded belly as if breaking through old skin, flowing forth like a wave. A skull rests on the sand, recalling Catholic Crucifixion scenes and memento mori paintings of classical antiquity. Staring out at the viewer with the wide grin of a clown, the skull pokes fun at our sense of horror, death, and change. An anole lizard, also native to Houston, glowing acidic green against the misty seascape, looks on as a witness, with its tiny hands gathered in prayer.

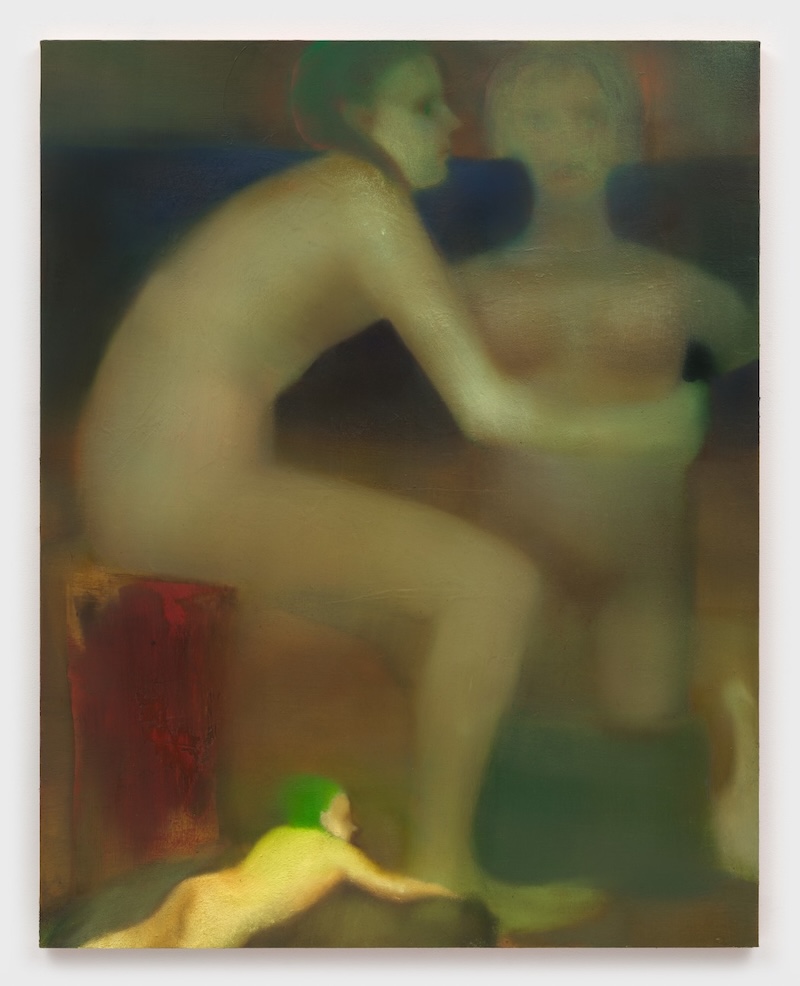

In other paintings such as Holy Fury, 2025, the viewer is confronted by a front-facing figure, viewed from close-up as she floats to the surface. Frozen in place, her eyes are wide open with terror as a miniature apparition swims out from her mouth directly towards the viewer. Here, exorcism becomes another form of birth. The mouth, taking the place of a pregnant belly, becomes a site of rupture, expulsion, and regeneration. Again, Glaessner flips our interpretive precepts by subverting what is often considered horrifying or threatening. As water levels continue to rise and our old familiar world dies, a new world is born. In Running Water, change, like water, is our only constant.