In a recent solo exhibition, Lyfe In a Strange Land, at Void Gallery in San Francisco, painter Yarrow Lazer-Smith (AKA Yarrow Slaps) presented a series of paintings that inspired imaginative possibilities within the troubling context of Western society’s once abundantly prevalent custom of slavery. The creative premise of Slap’s show is rooted in a hopeful reimagining of one of the darkest chapters in history: the transatlantic slave trade. Beginning in the 16th century, millions of Africans, mostly from Western and West-Central Africa, were captured and enslaved by American and European capitalists who thereafter transported them to the then-called New World, eventually into permanent bondage slavery.

During what was known as the Middle Passage – one leg of the triangular trade route that took goods (such as guns, ammunition, and cotton textiles) from Europe to Africa; then transported enslaved Africans to work in the Americas and West Indies; and finally delivered raw materials produced on the plantations (such as sugar, tobacco, indigo and cotton) back to Europe — the conditions aboard transporting ships were so distressing that many slaves revolted or took their own lives in acts of rebellion. Some mothers abandoned their own children overboard to keep them from suffering the inhumanity of slavery.

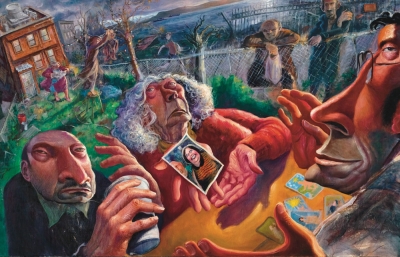

Slaps imagines what might have become of those children had they lived rather than drowned in these acts of protective infanticide. He began to visualize these ancestors of the sea, what he terms sea-ces-tors. Viewers are presented with an amalgamation of black figures triumphantly rising above whatever ocean chaos abounds. They are painted in oddly-shaped form, with jellyfish hair, and elongated limbs.

Slaps is audacious in his conceptualization of the historical moment. Imagining these infants morphing into sea creatures with fish-like appendages and other modified limbs and extremities, doesn’t explicitly invoke the slave trade, via iconography you might expect, instead Slaps hints at the crime endured. Distortion and misshaping abounds within the imagery that resonates because they are fully hinged to the violence that precedes them. Viewers intuitively can feel that some kind of transformation has preceded the rending of this inventive subject matter.

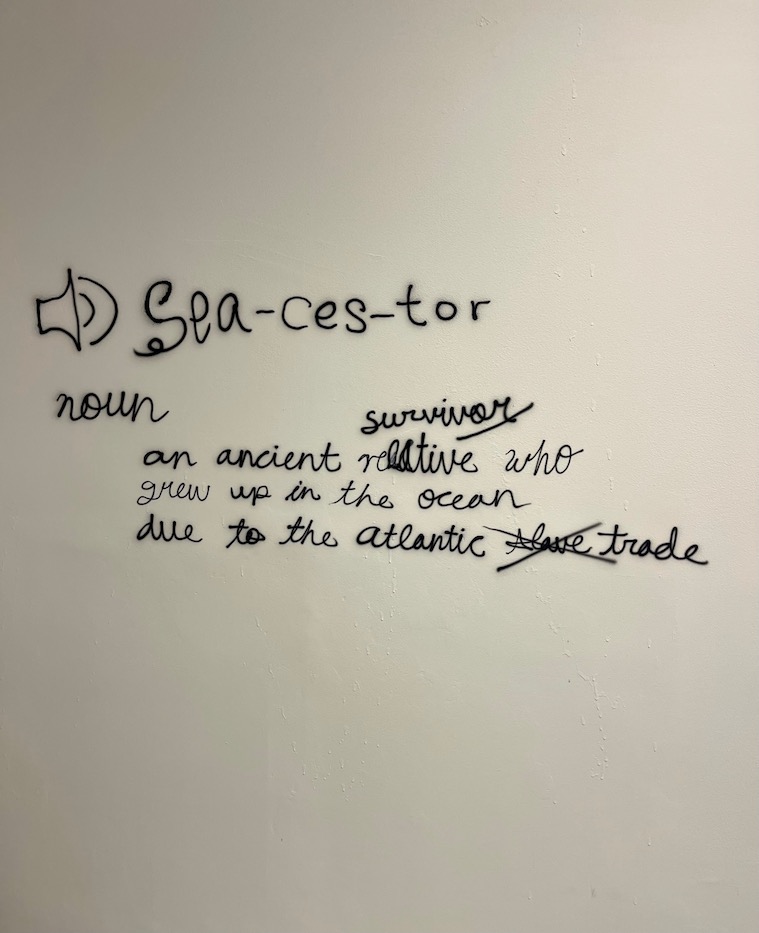

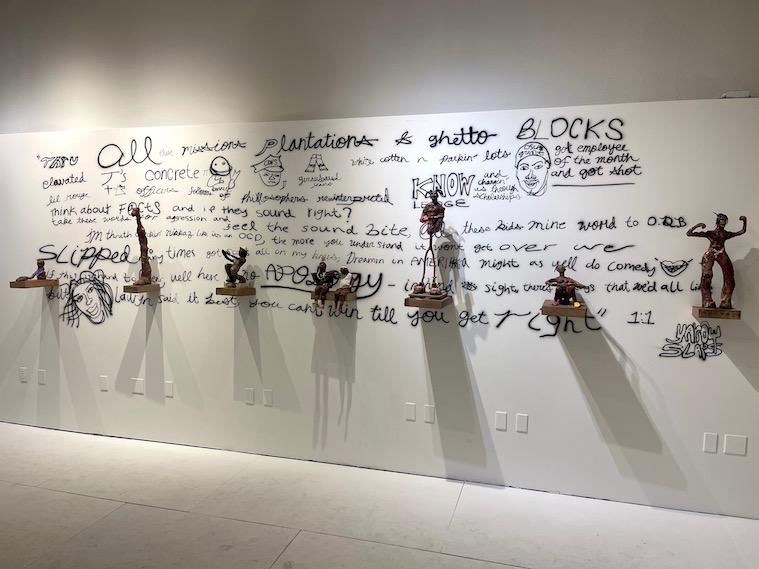

In writing theory, New Criticism eschewed the author’s intent in understanding a piece of writing preferring the notion that the work stood alone. The unavailability of the design or intention being, in some cases, impossible to gauge. Yet, a reconstruction can be built around hints in the text. Slaps utilizes internal evidence within the language of composition and human rendering to offer something unfamiliar that hints at something known, like syllables suggest words. Because convention is broken, just as irregular syntax or grammar might lead to narrative inquiry, Slaps’ imagery presents survival and mythological strength. Additionally, Slaps has scrawled apposite words on the walls of the gallery, including the definition of sea-ces-tor: “Noun. An ancient survivor/relative who grew up in the ocean due to the Atlantic slave trade.” Liberation is the theme that emerges: a resistance recoverable from the recontextualized historical moment.

Slaps’ use of diverse mediums creates a visual, overlapping pattern in the paintings that holds the viewers gaze. He paints with a dry pigment which he blends with matte medium and water. He mixes this with pastel, oil stick, acrylic paint, and utilizes airbrush. Most of the paintings are unstretched, and un-gessoed, raw canvas. In “Dem Archipelago$” (8 x 7 feet), he renders the arms with a rich brown pigment, followed by shading in airbrush or charcoal. He uses acrylic, pastel and oil stick to trace the outline of the primary figure, and a dash of silver pastel for the figure’s mouth. The resulting retracing of the same composition in different media creates an effective visual reverberation.

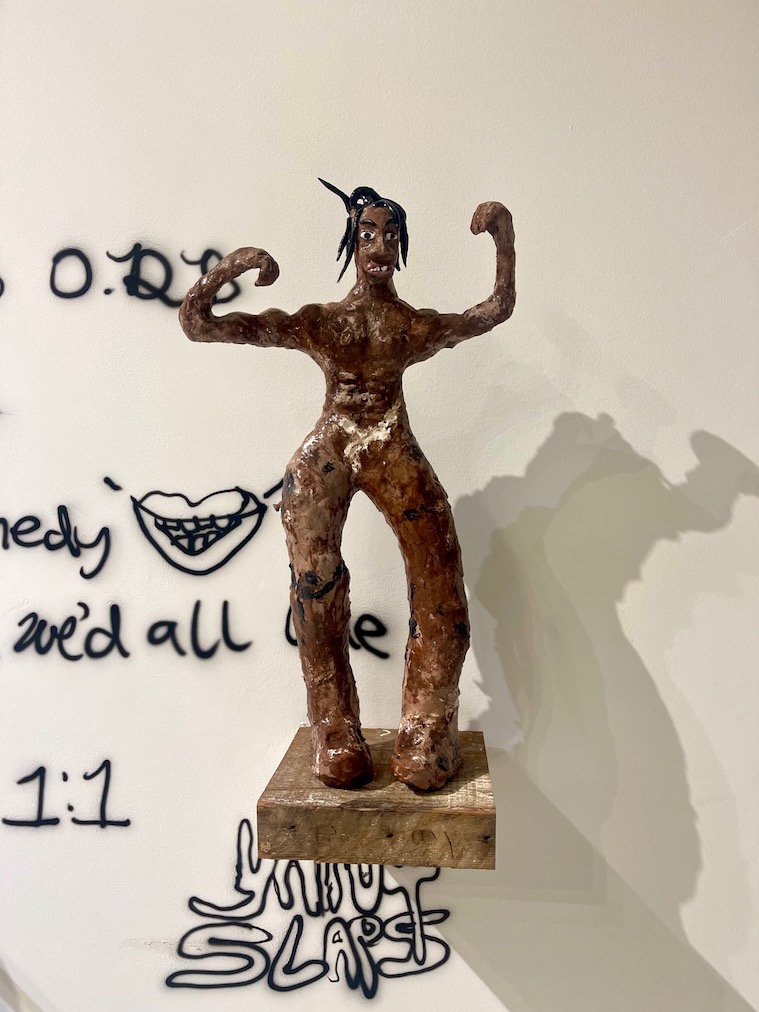

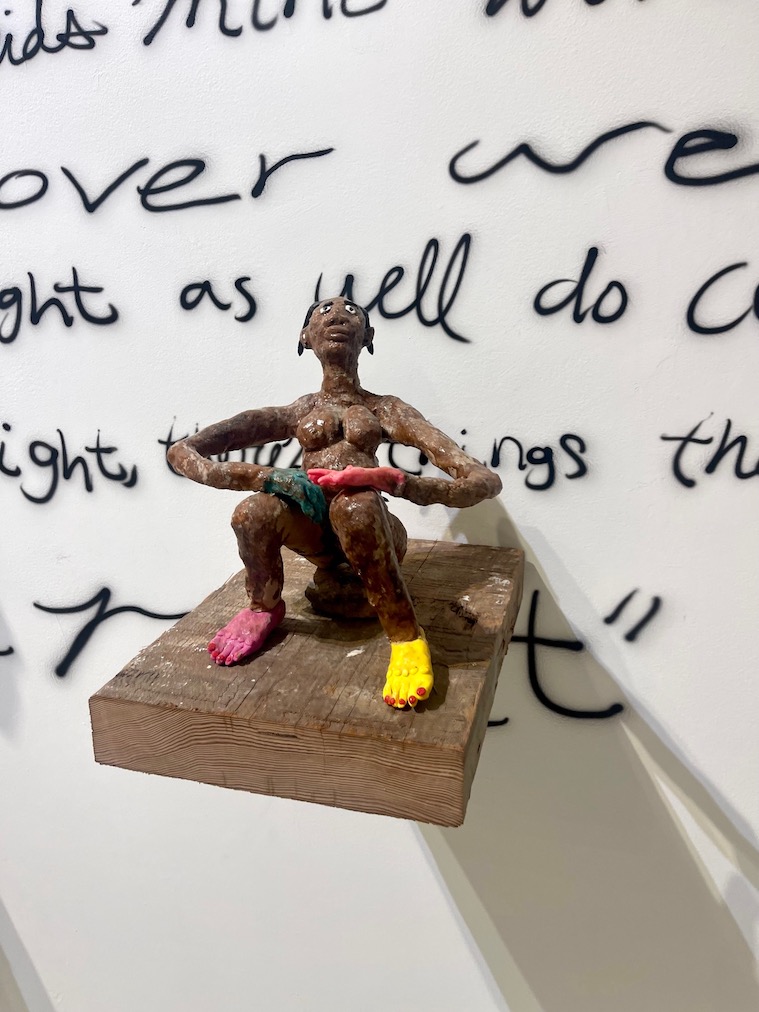

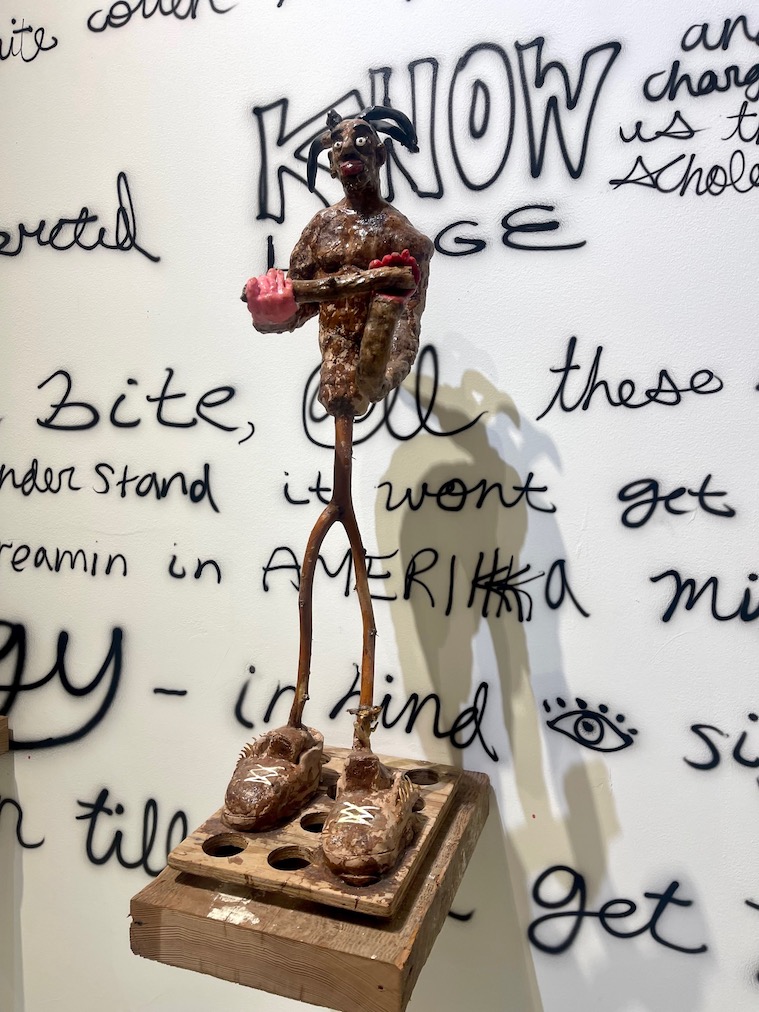

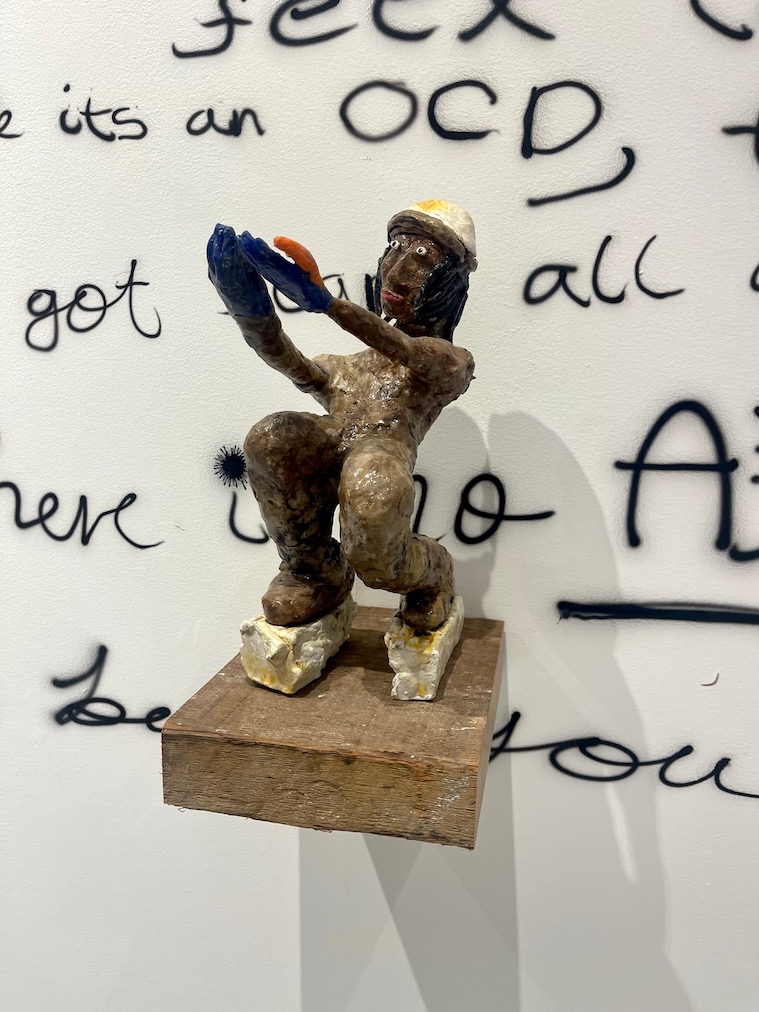

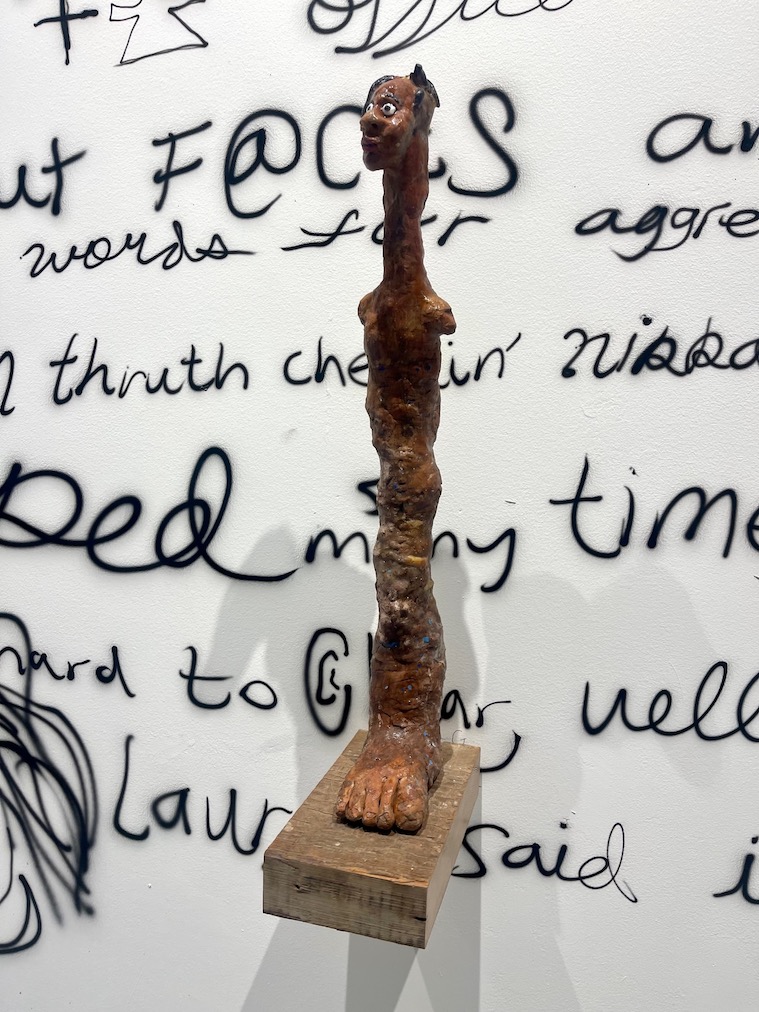

Accompanying the paintings are an array of figurative, hand-formed clay sculptures. Slaps allows nails and random things to be embedded in the clay, thus also holding them together. Referring to them as “Protectors” they represent some kind of spirit guardians. Exhibited like a line of ballet dancers, these figures conjure a troupe or company of defenders ready for battle or a performance.

Yarrow Slaps challenges us to heal with reimagination. He reappropriates a painful period in history, not content to look at scars as if a neutral observer or historian. He looks at the past to visualize his future self, to own his own transformation, to grow and elevate toward a brighter potential. —Matt Gonzalez