To speak of a country or land of the sun in reference to Salah Elmur’s paintings is to immerse oneself in the Sudan of Khartoum and the banks of the Nile, where the artist spent his childhood. It was after a spell in prison for a cartoon that was too critical of the government that Salah Elmur had to leave Sudan for Kenya in the 1990s, before settling in Egypt years later following his marriage. In Egypt, Elmur perceives echoes of Sudan: both countries are deeply bound by colonial history and the shared British and Egyptian domination over his people.

Salah Elmur, above all, is a painter of people emerging from his own history and childhood. Through recurring figures of peasants, fishermen, and laborers inhabiting a pastoral world, he creates a portrait that is simultaneously autobiographical and collective, while exceeding national boundaries—depicting a community both real and imagined. While Sudan predominates, it is the biographical triangle of Sudan, Kenya, and Egypt that imbues his paintings with cosmopolitanism and even a certain Pan-Africanism.

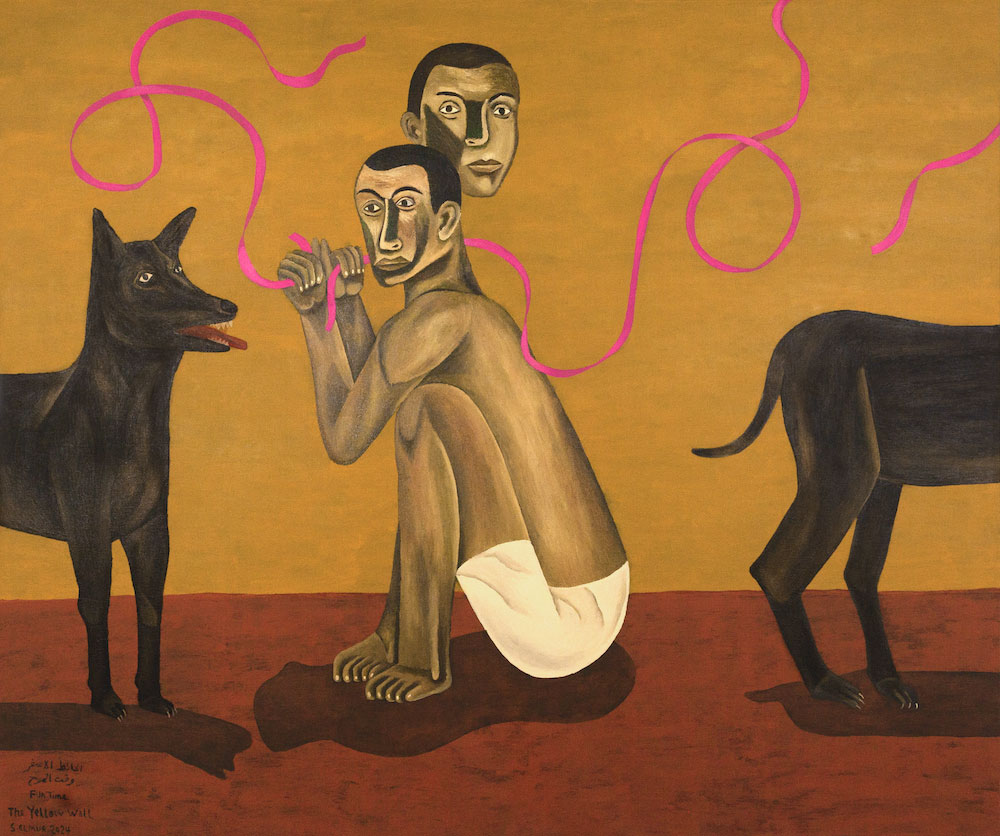

One of the major works in the exhibition, The Road to the Fish Market (2024), portrays the people the artist carries in his heart and who are at the tip of his brush. Here, human characters and fish figures enter a more complex and metaphysical relationship than appearance and reality would suggest. The impossible compositions of anatomical fragments – double faces and severed heads – evoke a certain post-cubist energy, revisited through the eye of a graphic designer and film editor (activities that are part of Elmur’s artistic palette). Indeed, the gesture of workers carrying fish to the market could be mistaken for hands bearing a deity in a ritual procession. These animistic ways of relating to animals are continued in other paintings in the exhibition, such as Rabbit Performers (2024) and The Yellow Wall (2024), in which humans and animals are once again placed on the same level, in a spirit of mutual respect and ancestry.

The dialogue resonating with particular force in this Mexico City exhibition is Salah Elmur’s established connection to Diego Rivera's work. Both Elmur and Rivera devoted all their efforts to representing the people in a reformist, revolutionary and post-colonial spirit. Faced with Sudan's devastating situation, Elmur finds, in Mexico and Rivera's work, an example of a successful revolution (1910-1920). Like Rivera, he achieves a balance between a new form of 'socialist realism' - faithful to the people yet free of dogma - and 'magical realism,' expressed through multilayered actions and the monumentalization of figures within the landscape. One could also consider the links between Sudan, Egypt and Mexico, through their civilization and archaeological remains, making them great pre-colonial powers.

The Sudan revealed here is a country that is both timeless and anchored in cycles of work and economic production, as well as in children’s games and rituals of birth and mourning, as in Farewell Wall (2024). Various religious and animist practices emerge through clothing and gestures. As if standing on quicksand, identities and communities are both celebrated and thrown into crisis by the ultimate possibility that they might fail to coexist in harmony. Deep contradictions run through the gazes of Elmur's portrayed figures: loyalty and infidelity, dreams and obligations, prayer and blasphemy.

To speak of the land of the sun is also to speak of darkness, for a country like Sudan which has spent more time in conflict than at peace since its independence (1956). In his works, a seemingly childlike atmosphere gives way to a more political interpretation, a concern that lurks behind these deceptively innocent or naive faces. When faced with power structures such as the family, the army, the union, the classroom, etc., they respond by their mere presence. Furthermore, far from ignoring the tragedy of Sudan and its fractures between communities, Salah Elmur’s paintings are more than ever a storehouse of memories that are unfortunately being erased under the weight of bombs and atrocities.

What of the 'postcolonial' dimension of portraiture? Elmur paints the same face in thousands of variations to create a nation, an emancipated people that must rebuild itself but finds itself trapped by the same power structures that once oppressed it: the State, exploitation, racism. These faces—at once individual and collective—in their fragile attempt to form a family, become vectors of a melancholy that inaugurates the postcolonial paradigm; a paradigm born from the ruins of colonialism, whose threat remains constant even after independence. Thus, the melancholic figure of a man with Sudan's old flag against a wall stamped with revolutionary fists (The Old Flag Wall, 2024) appears as a wandering soul between a glorious past and an uncertain future.

Salah Elmur’s art is both epic - narrating history at the scale of the people, marked by significant dates and national events- and allegorical, immersed in a world that is fundamentally inaccessible and ineffable. —Morad Montazami