Anat Ebgi is pleased to announce Under the Rose, an exhibition by Marisa Adesman. This is Adesman’s first solo exhibition in New York and second with the gallery.

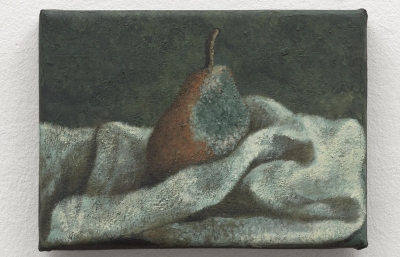

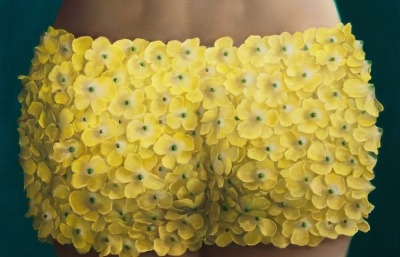

The seven paintings that comprise Under the Rose are an exquisite performance of dramatic tension: stillness under pressure, the moment before escape, the suspenseful beat before a trick is resolved. Adesman’s paintings represent the culmination of over two years’ worth of work. Narratively rich and formally detailed, the exhibition demands in-person viewing. Smooth and luminous, built through hundreds of layers of glazing, Adesman achieves a glass-like surface that recalls Dutch still life painting rendered with a contemporary slickness. Her obsessive technique captures hyperreal droplets of blood, stained glass, delicate petals, ripe fruit, and soft flesh with meticulous focus.

Adesman’s work draws on the tradition of Vanitas, though the logic is theatrical rather than moral. Inspired by painters such as Raphaelle Peale and informed by surrealism and ancient Greek mythology, these paintings present predicaments, tricks, and visual spells. Where there is emotional logic, Adesman manipulates expectations; where there is implicit violence, she tempers the scene with elegance. Narrative is complicated by contradiction.

The exhibition’s title, Under the Rose, derives from the Latin phrase sub rosa, an ancient symbol of secrecy. In Roman banquets, a rose would be suspended above gatherings to signal confidentiality, a tradition later echoed in Renaissance parlors and domestic interiors. Across these paintings, Adesman transforms domestic spaces—historically associated with passivity, beauty, or feminine restraint—into a stage for private disobedience, erotic tension, and emotional precision. The rose, long a symbol of love, purity, suffering, and resistance, becomes a cipher for everything that transpires behind closed doors. These paintings are both witness and participant in a theater of secrecy, where rituals unfold unseen and beauty masks transformation.

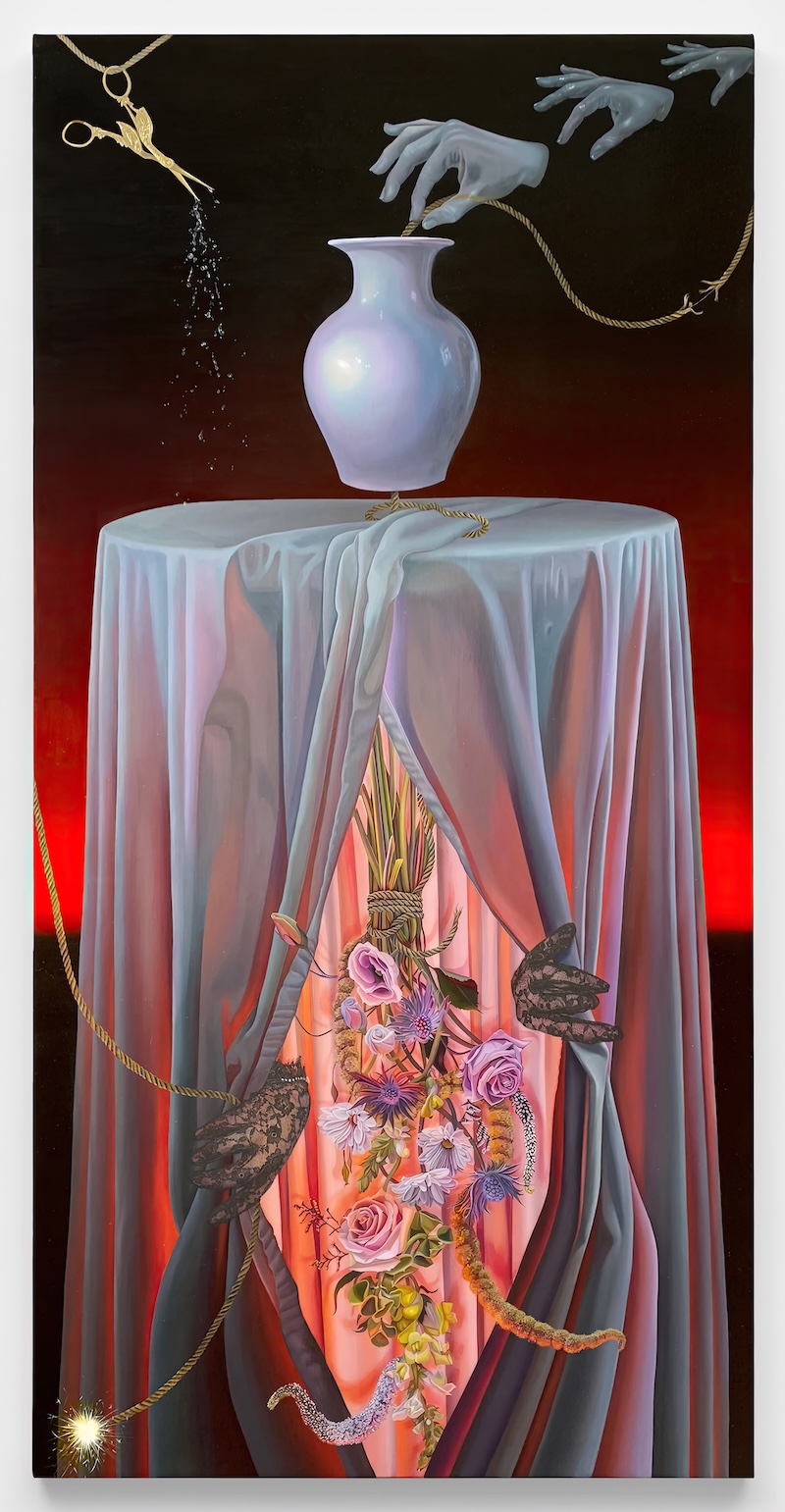

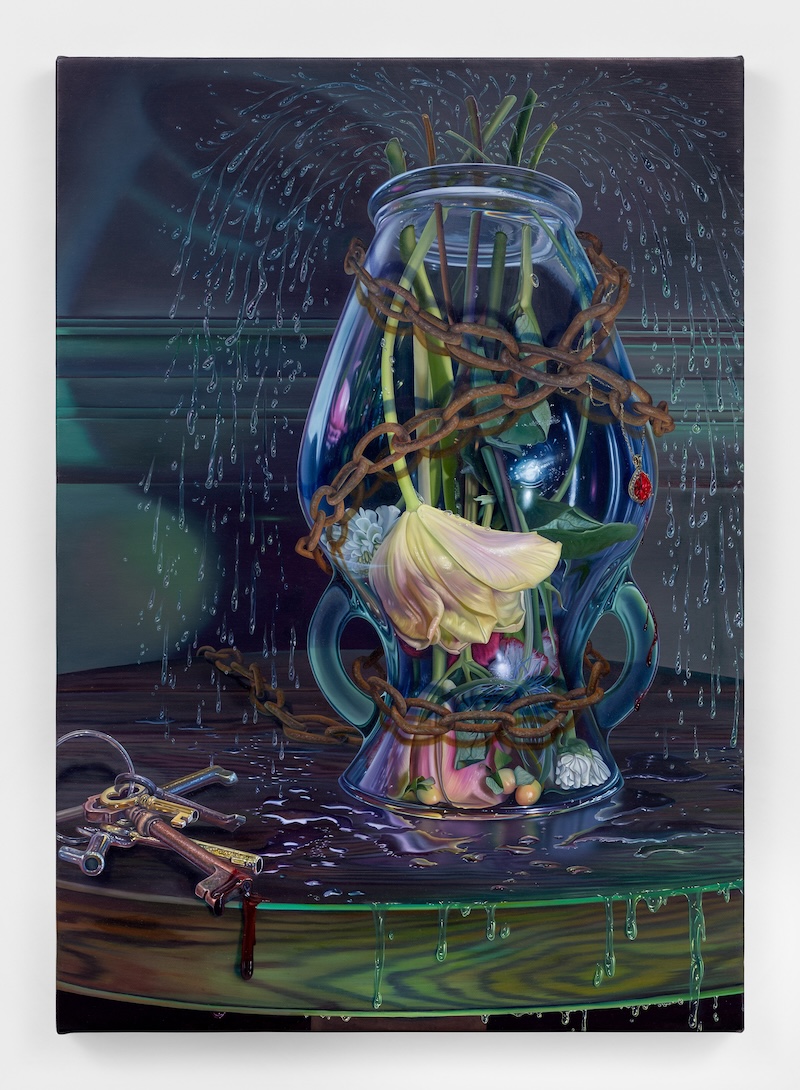

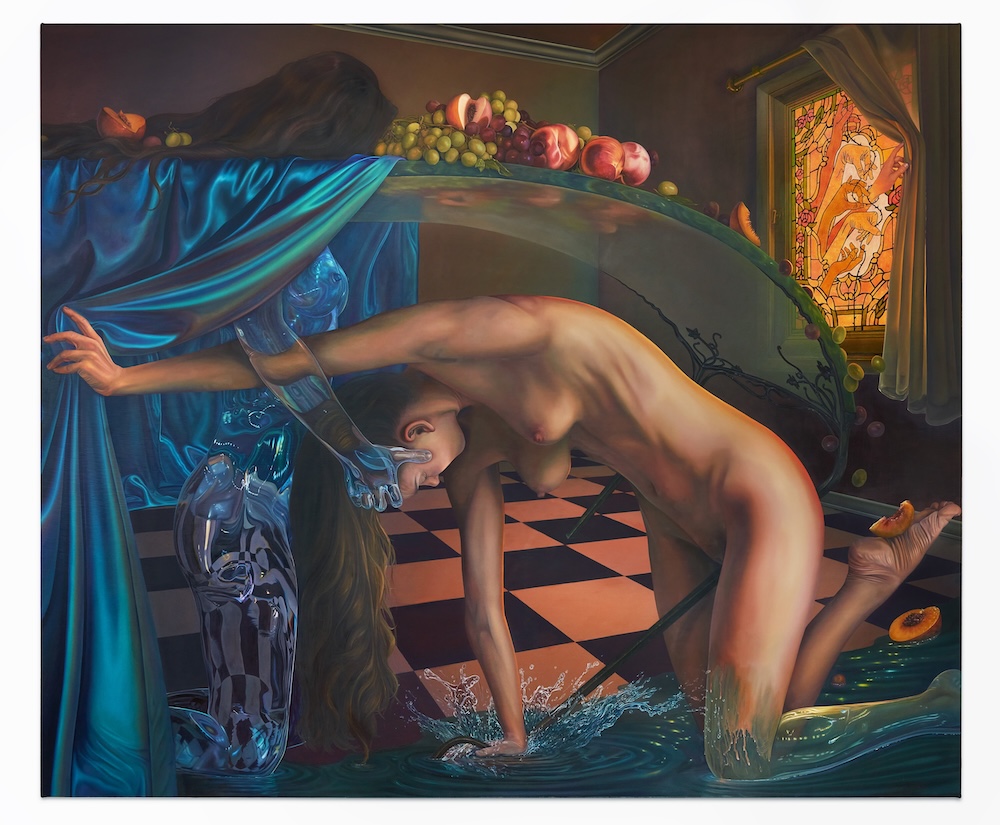

Several works explore chaotic scenes of psychosexual fantasy and mythopoetic enchantment. Predicament Escape (2024) depicts a vase of flowers, limp, submerged, and inverted on a table top. The trapped flowers are cinched and bound by a rusted chain, dramatizing the risk of escape. Teasing release, Adesman leaves the keys in view. The composition is a spectacle of immobilization, something precious frozen in its own beauty and erotic containment. June Drop (2024) pictures two women, a glass figure cradling the head of a flesh figure balancing the surrounding chaos and subjugation with an act of healing or absolution. Adesman’s alchemic transfigurations of flesh to glass or solid to liquid situate the reality within a visionary world.

Shadows and silhouettes form a continuous motif in Adesman’s works. Mischievous agents of uncertainty, they mark unseen forces, introduce narrative action, and provide as much meaning as solid forms. A shrouded bouquet in The Turn (2025) appears to have been cut by a knife, drops of blood stain the satin cloth. This scrim forms the edge of exposure – a barrier evoking memory, traces rather than pure spectacle. We cannot be sure why things are happening, as only the partially veiled aftermath is visible. Are these acts of ritual and ceremony, or torture and mayhem? Do these figures, flowers, and fruits have their own agency, or are they subject to larger constructed natural forces? Adesman presses on the edges of fantasy, rather than escaping into it.

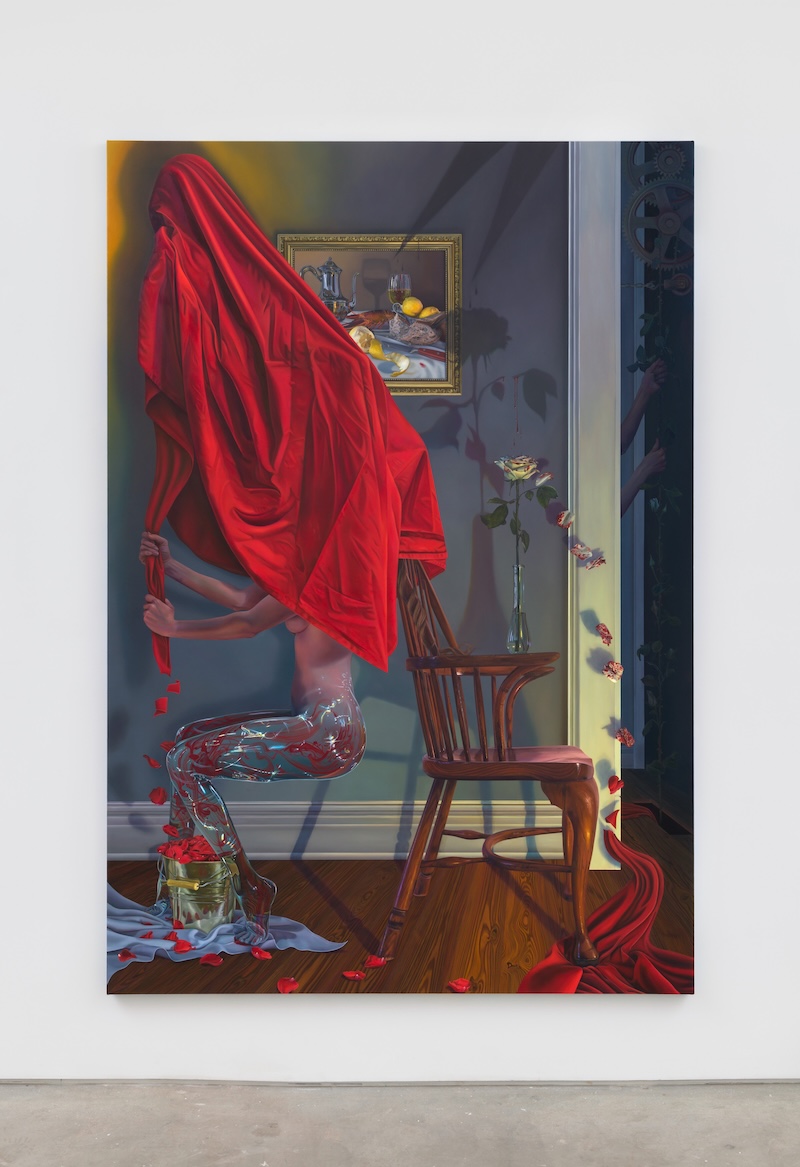

Mystery and calm punctuate moments of intensity. In Tug of War (2025), Adesman reimagines the reclining nude; however, draped in heavy red fabric, the only direct form appears as a gloved hand resting on the hips. Adesman notes that such depictions of domestic life were “historically dismissed as decorative or passive,” in her reimaginings, they “serve as a stage where intimacy, power, resistance, or whatever else we are thirsty for, can play out.” From the chinoiserie to the stained glass, the decorative surfaces of the room serve as stages for these dramas and contradictions.

Elsewhere, too, the body is displaced, obscured, or vanishing. The largest canvas in the exhibition, Deadheading (2025), depicts a figure seated in midair, frozen in her transformation between flesh and molten transparency. Hidden in a doorway, disembodied hands pull a lever made of vines. Gears slip into motion. Petals drift, scissors cut, and shadows fall, everything mechanistically to plan. Adesman presents care and violence not as opposites, but as mutually entangled forces.

The exhibition unfolds like a magic trick: the pledge, the turn, and finally, the prestige. What is visible can’t be trusted. A table of preparatory drawings on translucent paper accompanies the paintings. Offering a glimpse behind the curtain of process, Adesman invites viewers to witness the illusion being constructed, even as the final result remains opaque. Glass, fabric, metal, water—her rendered materials behave less like props and more like agents, enacting states of containment and dissolution. Considered as actors, these inanimate objects flicker between feeling and function, seduction and threat, wound and surface, illusion and evidence. Adesman’s work dwells in this tension, animating a world that is both precise and destabilizing: where beauty is unstable, evidence is misdirection, and the familiar remains just out of reach.